The Love for Three Oranges (fairy tale)

| The Love for Three Oranges | |

|---|---|

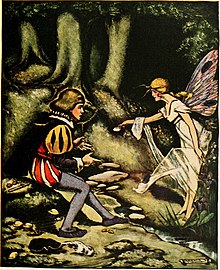

The prince releases the fairy woman from the fruit. Illustration by Edward G. McCandlish for Édouard René de Laboulaye's Fairy Book (1920). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Love for Three Oranges |

| Also known as | The Three Citrons |

| Data | |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 408 (The Three Oranges) |

| Region | Italy |

| Published in | Pentamerone, by Giambattista Basile |

| Related | The Enchanted Canary Lovely Ilonka |

"The Love for Three Oranges" or "The Three Citrons" is an Italian literary fairy tale written by Giambattista Basile in the Pentamerone.[1] It is the concluding tale, and the one the heroine of the frame story uses to reveal that an imposter has taken her place.

Summary[]

A king, who only had one son, anxiously waited for him to marry. One day, the prince cut his finger; his blood fell on white cheese. The prince declared that he would only marry a woman as white as the cheese and as red as the blood, so he set out to find her.

The prince wandered the lands until he came to the Island of Ogresses, where two little old women each told him that he could find what he sought here, if he went on, and the third gave him three citrons, with a warning not to cut them until he came to a fountain. A fairy would fly out of each, and he had to give her water at once.

He returned home, and by the fountain, he was not quick enough for the first two, but was for the third. The woman was red and white, and the prince wanted to fetch her home properly, with suitable clothing and servants. He had her hide in a tree. A black slave, coming to fetch water, saw her reflection in the water, and thought it was her own and that she was too pretty to fetch water. She refused, and her mistress beat her until she fled. The fairy laughed at her in the garden, and the slave noticed her. She asked her story and on hearing it, offered to arrange her hair for the prince. When the fairy agreed, she stuck a pin into her head, and the fairy only escaped by turning into a bird. When the prince returned, the slave claimed that wicked magic had transformed her.

The prince and his parents prepared for the wedding. The bird flew to the kitchen and asked after the cooking. The lady ordered it be cooked, and it was caught and cooked, but the cook threw the water it had been scalded in, into the garden, where a citron tree grew in three days. The prince saw the citrons, took them to his room, and dealt with them as the last three, getting back his bride. She told him what had happened. He brought her to a feast and demanded of everyone what should be done to anyone who would harm her. Various people said various things; the slave said she should be burned, and so the prince had the slave burned.

Analysis[]

It is Aarne-Thompson type 408, and the oldest known variant of this tale.[2] Scholarship point that the Italian version is the original appearance of the tale, with later variants appearing in French, such as the one by Le Chevalier de Mailly (Incarnat, blanc et noir (fr)).[3] In de Mailly's version, the fruits the girls are trapped in are apples.[4][5][6]

While analysing the imagery of the golden apples in Balkanic fairy tales, researcher Milena Benovska-Sabkova took notice that the fairy maiden springs out of golden apples in these variants, fruits that are interpreted as having generative properties.[7]

Scholar Linda Dégh suggested a common origin for tale types ATU 403 ("The Black and the White Bride"), ATU 408 ("The Three Oranges"), ATU 425 ("The Search for the Lost Husband"), ATU 706 ("The Maiden Without Hands") and ATU 707 ("The Three Golden Sons"), since "their variants cross each other constantly and because their blendings are more common than their keeping to their separate type outlines" and even influence each other.[8][a][b]

The transformations and the false bride[]

The tale type is characterized by the substitution of the fairy wife for a false bride. The usual occurrence is when the false bride (a witch or a slave) sticks a magical pin into the maiden's head or hair and she becomes a dove.[c] In some tales, the fruit maiden regains her human form and must bribe the false bride for three nights with her beloved.[13]

In other variants, the maiden goes through a series of transformations after her liberation from the fruit and regains a physical body.[d] In that regard, according to Christine Shojaei-Kawan's article, Christine Goldberg divided the tale type into two forms: one subtype AaTh 408A, wherein the fruit maiden suffers the cycle of metamorphosis, and subtype AaTh 408B, wherein the girl transforms into a dove by the needle.[15]

Separated from her husband, she goes to the palace (alone or with other maidens) to tell tales to the king. She shares her story with the audience and is recognized by him.[16]

Parallels[]

The series of transformations attested in these variants (from animal to tree to tree splinter or back into the fruit whence she came originally) has been compared to a similar motif in the Ancient Egyptian story of The Tale of Two Brothers.[17]

Variants[]

Origins[]

Scholar Jack Zipes suggests that the story "may have originated" in Italy, with later diffusion to the rest of Southern Europe and into the Orient.[18]

Richard McGillivray Dawkins, on the notes on his book on Modern Greek Folktales in Asia Minor, suggested a Levantine origin for the tale, since even Portuguese variants retain an Eastern flavor.[19]

According to his unpublished manuscript on the tale type, Walter Anderson concluded that the tale originated in Persia.[20]

Distribution[]

19th century Portuguese folklorist Consiglieri Pedroso stated that the tale was "familiar to the South of Europe".[21] In the same vein, folklorist Stith Thompson suggested the tale had a regular occurrence in the Mediterranean Area, distributed along Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal.[22] French folklorist Paul Delarue, in turn, asserted that the highest number of variants are to be found in Turkey, Greece, Italy and Spain.[23]

Further scholarly research points that variants exist in Austrian, Ukrainian and Japanese traditions.[24] In fact, according to Spanish scholar Carme Oriol, the tale type is "well known" in Asia,[25] even in China and Korea.[26]

The tale type is also found in Africa and in America.[27]

Europe[]

Italy[]

A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage"), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found fifty-eight variants of the tale across Italian sources.[28] In fact, this country holds the highest number of variants, according to scholarship.[29]

Italo Calvino included a variant The Love of the Three Pomegranates, an Abruzzese version known too as As White as Milk, As Red as Blood but noted that he could have selected from forty different Italian versions, with a wide array of fruit.[30] For instance, the version The Three Lemons, published in The Golden Rod Fairy Book[31] and Vom reichen Grafensohne ("The Rich Count's Son"), where the fruits are Pomeranzen (bitter oranges).[32]

In a Sicilian variant, collected by Laura Gonzenbach, Die Schöne mit den sieben Schleiern ("The Beauty with Seven Veils"), a prince is cursed by an ogress to search high and low for "the beauty with seven veils", and not rest until he finds her. The prince meets three hermits, who point him to a garden protected by lions and a giant, In this garden, there lies three coffers, each one holding a veiled maiden inside. The prince releases the maiden, but leaves her by a tree and returns to his castle. He kisses his mother and forgets his bride. One year later, he remembers the veiled maiden and goes back to her. When he sights her, he finds "an ugly woman". The maiden was transformed into a dove.[33] Laura Gonzenbach also commented that the tale differs from the usual variants, wherein the maiden appears out of a fruit, like an orange, a citron or an apple.[34]

Spain[]

North American folklorist Ralph Steele Boggs (de) stated that the tale type was very popular in Spain, being found in Andalusia, Asturias, Extremadura, New and Old Castile.[35]

According to Spanish folklorist Julio Camarena (es), the tale type, also known as La negra y la paloma ("The Black Woman and the Dove"), was one of the "more common" (más usuales) types found in the Province of Ciudad Real.[36]

Northern Europe[]

Despite a singular attestation of the tale in a Norwegian compilation of fairy tales, its source was a foreign woman who became naturalized.[37]

Slovakia[]

Variants also exist in Slovakian compilations, with the fruits being changed for reeds, apples or eggs. Scholarship points that the versions where the maidens come out of eggs are due to Ukrainian influence, and these tales have been collected around the border. The country is also considered by scholarship to be the "northern extension" of the tale type in Europe.[38]

A Slovak variant was collected from Jano Urda Králik, a 78-year-old man from Málinca (Novohrad) and published by linguist Samuel Czambel (sk). In this tale, titled Zlatá dievka z vajca ("The Golden Woman from the Egg"), in "Britain", a prince named Senpeter wants to marry a woman so exceptional she cannot be found "in the sun, in the moon, in the wind or under the sky". He meets an old woman who directs him to her sister. The old woman's sister points him to a willow tree, under which a hen with three eggs that must be caught at 12 o'clock if one wants to find a wife. After, they must go to an inn and order a hearty meal for the egg maiden, otherwise she will die. The prince opens the first two eggs in front of the banquet, but the maiden notices some dishes missing and perishes. With the third egg maiden, she survives. After the meal, the prince rests under a tree while the golden maiden from the egg walks about. She asks the innkeeper's old maid about a well, where the old maid shoves her into and she becomes a goldfish. The prince wakes up and thinks the old maid as his bride. However, the prince's companion notices it is not her, but refrains from telling the truth. They marry and a son is born to the couple. Some time later, the old king wishes for a drink of that well, and sends the prince's companion to fetch it. The companion grabs a bucket of water with the goldfish inside. He brings the goldfish to the palace, but the old maid throws the fish into the fire. A fish scale survives and lodges between the boards of the companion's hut. He cleans up the hut and throws the trash in a pile of manure. A golden pear tree sprouts, which the false princess recognizes as the true egg princess. She orders the tree to be burnt down, but a shard remains and a cross is made out of it. An old lady who was praying in church finds the cross and takes it home. The cross begins to talk and the old lady gives it some food, and the golden maiden from the egg regains human form. They begin to live together and the golden maiden finds work at a factory. The prince visits the factory and asks her story, which she does not divulge. He returns the next day to talk to her and, through her tale, pieces the truth together. At last, he executes the false bride and marries the golden maiden from the egg.[39]

Slovenia[]

In a Slovenian variant named The Three Citrons, first collected by author Karel Jaromír Erben, the prince is helped by a character named Jezibaba (an alternative spelling of Baba Yaga). At the end of the tale, the prince restores his fairy bride and orders the execution of both the false bride and the old grandmother who told the king about the three citrons.[40] Walter William Strickland interpreted the tale under a mythological lens and suggested it as part of a larger solar myth.[41] published a very similar version and sourced his as "Czechoslovak".[42]

Croatia[]

In a Croatian variant from Varaždin, Devojka postala iz pomaranče ("The Maiden out of the Pomerances"), the prince already knows of the magical fruits that open and release a princess.[43]

A Croatian storyteller from near Daruvar provided a variant of the tale type, collected in the 1970s.[44]

Ukraine[]

Professor Andrejev noted that the tale type 408, "The Love for Three Oranges", showed 7 variants in Ukraine.[45]

Poland[]

In a Polish variant from Dobrzyń Land, Królówna z jajka ("The Princess [born] out of an egg"), a king sends his son on a quest to marry a princess born out of an egg. He finds a witch who sells him a pack of 15 eggs and tells him that if any egg cries out for a drink, the prince should give them immediately. He returns home. On the way, every egg screams for water, but he fails to fulfill their request. Near his castle, he drops the last egg on water and a maiden comes out of it. He goes back to the castle to find some clothes for her. Meanwhile, the witch appears and transforms the maiden into a wild duck. The prince returns and notices the "maiden"'s appearance. They soon marry. Some time later, the gardener sees a golden-feathered duck in the lake, which the prince wants for himself. While the prince is away, the false queen orders the cook to roast the duck and to get rid of its blood somewhere in the garden. An apple tree with seven blood red apples sprouts on its place. The prince returns and asks for the duck, but is informed of its fate. When strolling in the garden, he notices a sweet smell coming from the apple tree. He orders a fence to be built around the tree. After he goes on a trip again, the false queen orders the apples to be eaten and the tree to be felled down and burned. A few wood chips remain in the yard. An old woman grabs hold of them to make a fire, but one of the woodchips keeps jumping out of the fire. She decides to bring it home with her. When the old lady goes out to buy bread, the egg princess comes out of the woodchip to clean the house and returns to that form before the old lady comes home at night. This happens for two days. On the third day, the old lady discovers the egg maiden and thanks her. They live together, the egg maiden now permanently in human form, and the prince, feeling sad, decides to invite the old ladies do regale him with tales. The egg maiden asks for the old lady for some clothes so she can take part in the gathering. Once there, she begins to tell her tale, which the false queen listens to. Frightened, she orders the egg maiden to be seized, but the prince recognizes her as his true bride and executes the false queen.[46]

Polish ethnographer Stanisław Ciszewski (pl) collected another Polish variant, from Smardzowice, with the name O pannie, wylęgniętej z jajka ("About the girl hatched from an egg"). In this story, a king wants his son to marry a woman who is hatched from an egg. Seeking such a lady, the prince meets an old man who gives him an egg and tells him to drop it in a pool in the forest and wait for a maiden to come out of it. He does as he is told, but becomes impatient and breaks open the egg still in the water. The maiden inside dies. He goes back to the old man, who gives him another egg and tells him to wait patiently. This time a maiden is born out of the egg. The prince covers her with his cloak takes her on his horse back to his kingdom. He leaves the egg girl near a plantation and goes back to the palace to get her some clothes. A nearby reaper maid sees the egg girl and drowns her, replacing her as the prince's bride. The egg maiden becomes a goldfish which the false queen recognizes and orders to be caught to make a meal out of it. The scales are thrown out and an apple tree sprouts on the spot. The false bride orders the tree to be cut down. Before the woodcutter fulfills the order, the apple tree agrees to be cut down, but requests that someone take her woodchips home. They are taken by the bailiff. Whenever she goes out and returns home, the entire house is spotless, like magic. The mystery of the situation draws the attention of the people and the prince, who visits the old lady's house. He sees a woman going to fetch water and stops her. She becomes a snake to slither away, but the man still holds on to her. She becomes human again and the man recognizes her as the egg maiden. He takes her home and the false bride drops dead when she sees her.[47]

Hungary[]

Variants of the tale are also present in compilations from Hungary. Scholar Hans-Jörg Uther remarks that the tale type is "quite popular" in this country, with 79 variants registered.[48] Usually, the fairy maiden comes out of a plant ("növényből").[49]

Fieldwork conducted in 1999 by researcher Zoltán Vasvári amongst the Palóc population found 3 variants of the tale type.[50]

One tale was collected by with the title A nádszál kisasszony[51] and translated by Jeremiah Curtin as The Reed Maiden.[52] In this story, a prince marries a princess, the older sister of the Reed Maiden, but his brother only wants to marry "the most lovely, world-beautiful maiden". The prince asks his sister-in-law who this person could be, and she answers it is her elder sister, hidden with her two ladies-in-waiting in three reeds in a distant land. He releases the two ladies-in-waiting, but forgets to give them water. The prince finally releases the Reed Maiden and gives her the water. Later, before the Reed Maiden is married to the prince, a gypsy comes and replaces her.

Another variant is Lovely Ilonka, collected by and also published by Andrew Lang. In this tale, the prince quests for a beautiful maiden to marry and asks an old lady. The old woman points him to a place where three bulrushes grow and warns him to break the bulrushes near a body of water.

In another variant by Elisabeth Rona-Sklárek, Das Waldfräulein ("The Maiden in the Woods"), a lazy prince strolls through the woods and sights a beautiful "Staude" (a perennial plant). He uses his knife to cut some of the plant and releases a maiden. Stunned by her beauty, he cannot fulfill her request for water and she disappears. The same thing happens again. In the third time, he gives some water to the fairy maiden and marries her. The fairy woman gives birth to twins, but the evil queen mother substitutes them for puppies. The babies, however, are rescued a pair of two blue woodpeckers and taken to the woods. When the king returns from war and sees the two animals, he banishes his wife to the woods.[53]

Antal Hoger collected the tale A háromágú tölgyfa tündére ("The Fairy from Three-Branched Oak Tree"). A king goes hunting in the woods, but three animals plead for their lives (a deer, a hare and a fox). All three animals point to a magical oak tree with three branches and say, if the king break each of the branches, a maiden shall appear and request water to drink. With the first two branches, the maidens die, but the king gives water to the third one and decides to marry her. They both walk towards the castle and the king says the fairy maiden should wait on the tree. A witch sees the maiden, tricks her and tosses her deep in a well; she replaces the fairy maiden with her own daughter.[54] He also cited two other variants: A tündérkisasszony és a czigányleány ("The Fairy Princess and the Gypsy Girl"), by Laszló Arányi, and A három pomarancs ("The Three Bitter Oranges"), by Jánós Érdelyi.[55]

German philologist Heinrich Christoph Gottlieb Stier (de) collected a Hungarian variant from Münster titled Die drei Pomeranzen ("The Three Bitter Oranges"): an old lady gives three princely brothers a bitter orange each and warns them to crack open the fruit near a body of water. The first two princes disobey and inadvertently kill the maiden that comes out of the orange. Only the youngest prince opens near a city fountain and saves the fairy maiden. Later, a gypsy woman replaces the fairy maiden, who turns into a fish and a tree and later hides in a piece of wood.[56] The tale was translated and published into English as The Three Oranges.[57]

In the tale A gallyból gyött királykisasszony ("The Princess from the Tree Branch"), a prince that was hunting breaks three tree branches in the forest and a maiden appears. The prince takes her to a well to wait for him to return with his royal retinue. An ugly gypsy woman approaches the girl and throws her down the well, where she becomes a goldfish.[58]

English scholar A. H. Wratislaw collected the tale The Three Lemons from a Hungarian-Slovenish source and published it in his Sixty Folk-Tales from Exclusively Slavonic Sources. In this tale, the prince goes on a quest for three lemons on a glass hill and is helped by three old Jezibabas on his way. When he finds the lemons and cracks open each one, a maiden comes out and asks if the prince has prepared a meal for her and a pretty dress for her to wear. When he saves the third maiden, she is replaced by a gypsy maidservant who sticks a golden pin in her hair and transforms the fruit maiden into a dove.[59] The tale was originally published by Slovak writer Ján Francisci-Rimavský (Johann Rimauski).[60]

In another tale from Elek Benedek's collection, Les Trois Pommes ("The Three Apples"), translated by Michel Klimo, the king's three sons go on a quest for wives. They meet a witch who gives each of them an apple and warns them to open near a fountain. The two oldest princes forget her warning and the fairy maiden dies. The third one opens near a fountain and saves her. He asks her to wait near a tree. A "bohemiénne" arrives to drink from the fountain and shoves the fairy maiden down the well, where she becomes a little red fish. The bohemiénne substitutes the fairy maiden and requests the prince to catch the red fish. She then asks the cook to make a meal out of it and to burn every fish scale. However, a scale survives and becomes a tree. The bohemiénne notices the tree is her rival and asks for the tree to be felled down. Not every part of the tree is destroyed: the woodcutter hides away part of the wood to make a pot lid.[61]

In the tale A Tökváros ("The Pumpkin Town" or "Squash City"),[62] by Elek Benedek, the son of a poor woman is cursed by a witch that he may not find a wife until he goes to Pumpkin City, or eats down three iron-baked loaves of bread. He asks his mother to bake the iron bread and goes his merry way. He finds three old women in his travels and gives each the bread. The third reveals the location of the City of Pumpkins and warns him to wait on three squashes in a garden, for, during three days, a maiden shall appear out of one on each day. He does exactly that and gains a wife. They leave town and stop by a well. He tells the pumpkin maiden to wait by the well while he goes home to get a wagon to carry them the rest of the way. Suddenly, an old gypsy woman pushes her into the well and takes her place. When the youth returns, he wonders what happened to her, but seems to accept her explanation. He bends to drink some water from the well, but the false bride convinces him not to. He sees a tulip in the well, plucks it and takes it home. When the youth and the false bride go to church, the maiden emerges from the tulip. One night, the youth awakes to see the pumpkin maiden in his room, discovers the truth and expels the old gypsy.[63]

In a different variaton of the tale type, A griffmadár leánya ("The Daughter of the Griffin Bird"), a prince asks his father for money to use on his journey, and the monarch tells his son he is not to return until he is married to the daughter of the griffin bird. The prince meets an old man in the woods who directs him to a griffin's nest, with five eggs. The prince grabs all five eggs and cracks them open, a girl in a beautiful dress appearing out of each one. Only the last maiden survives because the prince gave her water to drink. He tells the maiden to wait by the well, but a gypsy girl arrives and, seeing the egg girl, throws her in the well and takes her place. The maiden becomes a goldfish and later a tree.[64]

In another tale with the egg, from Baranya, A tojásból teremtett lány ("The Girl who was created from an Egg"), the king asks his son to find a wife "just like his mother": "one who was never born, but created!" The prince, on his journeys, finds an egg on the road. He cracks open the egg and a maiden comes out of it; she asks for water to drink, but dies. This repeats with a second egg. With the third, the prince gives water to the egg-born maiden. He goes back to the castle to find her some clothes. While she awaits, a gypsy girl meets the egg maiden and throws her in the well. The gypsy maiden takes the place of the egg girl and marries the prince. Some time later, an old gypsy shows the prince a goldfish he found in the well. The usual transformation sequence happens: the false queen wants to eat the fish; a fish scale falls to the ground and becomes a rosewood; the gypsy wants the rosewood to be burnt down, but a splinter remains. At the end of the tale, the egg princess regains her human form and goes to a ceremony of kneading corn, and joins the other harvesters in telling stories to pass time. She narrates her life story and the king recognizes her.[65]

Greece[]

Austrian consul Johann Georg von Hahn collected a variant from Asia Minor titled Die Zederzitrone. The usual story happens, but, when the false bride pushed the fruit maiden into the water, she turned into a fish. The false bride then insisted she must eat the fish; when the fish was gutted, three drops of blood fell to the floor and from them sprouted a cypress. The false bride then realized the cypress was the true bride and asked the prince to chop down the tree and burn it, making some tea with its ashes. When the pyre was burning, a splinter of the cypress got lodged in an old lady's apron. When the old lady left home for a few hours, the maiden appeared from the splinter and swept the house during the old woman's absence.[66] Von Hahn remarked that this transformation sequence was very similar to one in a Wallachian variant of The Boys with the Golden Stars.[67]

Romania[]

Writer and folklorist Cristea Sandu Timoc noted that Romanian variants of the tale type were found in Southern Romania, where the type was also known as Fata din Dafin ("The Bay-Tree Maiden").[68]

In a Romanian variant collected by Arthur and Albert Schott from the Banat region, Die Ungeborene, Niegesehene ("The Not-Born, Never Seen [Woman]"), a farmer couple prays to God for a son. He is born. Whenever he cries, his mother rocks his sleep by saying he will marry "a woman that was not born nor any man has ever seen". When he comes of age, he decides to seek her. He meets Mother Midweek (Wednesday), Mother Friday and Mother Sunday. They each give him a golden apple and tell him to go near a water source and wait until a maiden appears; she will ask for a drink of water and after he must give her the apple. He fails the first two times, but meets a third maiden; he asks her to wait on top of a tree until he returns with some clothes. Some time later, a "gypsy girl" comes and sees the girl. She puts a magic pin on her hair and turns her into a dove.[69]

In another Romanian variant, Cele trei rodii aurite ("The Three Golden Pomegranates"), the prince is cursed by a witch to never marry until he finds the three golden pomegranates.[70]

Balkans[]

The tale type is said to be "widespread in the Balkans", with the name "Неродената мома" ("The Maiden That Was Never Born").[71]

Cyprus[]

At least one variant from Cyprus, from the "Folklore Archive of the Cyprus Research Centre", shows a merger between tale type ATU 408 with ATU 310, "The Maiden in the Tower" (Rapunzel).[72]

Malta[]

In a variant from Malta, Die sieben krummen Zitronen ("The Seven Crooked Lemons"), a prince is cursed by a witch to find the "seven crooked lemons". On an old man's advice, he grooms an old hermit, who directs him to another witch's garden. There, he finds the seven lemons, who each release a princess. Every princess asks for food, drink and garments before they disappear, but the prince helps only the last one. He asks her to wait atop a tree, but a Turksih woman comes and turns her into a dove.[73]

Asia[]

The tale is said to be "very popular in the Orient".[74] Scholar Ulrich Marzolph remarked that the tale type AT 408 was one of "the most frequently encountered tales in Arab oral tradition", albeit missing from The Arabian Nights compilation.[75]

Middle East[]

Scholar Hasan El-Shamy lists 21 variants of the tale type across Middle Eastern and North African sources, grouped under the banner The Three Oranges (or Sweet-Lemons).[76]

Iran[]

Professor Ulrich Marzolph, in his catalogue of Persian folktales, listed 23 variants of the tale type across Persian sources.[77]

A Persian variant, titled The Three Silver Citrons, was recorded by Katherine Pyle.[78]

Another Persian variant, The Orange and Citron Princess, was collected by Emily Lorimer and David Lockhart Robertson Lorimer, from Kermani. In this tale, the hero received the blessing of a mullah, who mentions the titular princess. The hero's mother advises against her son's quest for the maiden, because it would lead to his death. The tale is different in that there is only one princess, instead of the usual three.[79]

Turkey[]

The tale type also exists in Turkish oral repertoire, with the title Üç Turunçlar ("Three Citruses" or "Three Sour Oranges").[80] In fact, the Catalogue of Turkish Folktales, devised by Wolfram Eberhard and Peterv Boratav, registered 40 variants, being the third "most frequent folktale" after types AT 707 and AT 883A.[81]

A Turkish variant, titled The Three Orange-Peris, was recorded by Hungarian folklorist Ignác Kúnos.[82] The tale was translated as The Orange Fairy in The Fir-Tree Fairy Book.[83]

In Turkish variants, the fairy maiden is equated to the peri and, in several variants, manages to escape from the false bride in another form, such as a rose or a cypress.[84]

India[]

In a variant from Simla, in India, The Anar Pari, or Pomegranate Fairy, the princess released from the fruit suffers successive deaths ordered by the false bride, yet goes through a resurrective metamorphosis and regains her original body.[85]

As pointed by Richard McGillivray Dawkins, the Indian tale of The Bél-Princess, collected by Maive Stokes,[86] and The Belbati Princess, by Cecil Henry Bompas,[87] are "near relatives" of The Three Citrons, since the two Indian tales are about a beautiful princess hidden in a fruit and replaced by a false bride.[88]

At least one variant of the tale type has been collected in Kashmir.[89]

Japan[]

Japanese scholarship argues for some relationship between tale type ATU 408 and Japanese folktale Urikohime ("The Melon Princess"), since both tales involve a maiden born of a fruit and her replacement for a false bride (in the tale type) and for evil creature Amanojaku (in Japanese versions).[90] In fact, professor Hiroko Ikeda classified the story of Urikohime as type 408B in his Japanese catalogue.[91]

Popular culture[]

Theatre and opera[]

The tale was the basis for Carlo Gozzi's commedia dell'arte L'amore delle tre melarance,[92] and for Sergei Prokofiev's opera, The Love for Three Oranges.

Hillary DePiano's play The Love of the Three Oranges is based on Gozzi's scenario and offers a more accurate translation of the original Italian title, L'amore delle tre melarance, than the English version which incorrectly uses for Three Oranges in the title.

Literature[]

A literary treatment of the story, titled The Three Lemons and with an Eastern flair, was written by Lillian M. Gask and publish in 1912, in a folktale compilation.[93]

The tale was also adapted into the story Las tres naranjitas de oro ("The Three Little Golden Oranges"), by Spanish writer Romualdo Nogués.[94]

Bulgarian author Ran Bosilek adapted a variant of the tale type as his book "Неродена мома" (1926).[95]

Television[]

A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék ("Hungarian Folk Tales") (hu), with the title A háromágú tölgyfa tündére ("The Fairy from the Oak Tree"). This version also shows the fairy's transformation into a goldfish and later into a magical apple tree.

See also[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Lovely Ilonka

- Nix Nought Nothing

- The Bee and the Orange Tree

- The Enchanted Canary

- The Lassie and Her Godmother

- The Myrtle

Footnotes[]

- ^ On a related note, Stith Thompson commented that the episode of the heroine bribing the false bride for three nights with her husband occurs in variants of types ATU 425 and ATU 408.[9] In the same vein, scholar Andreas John stated that "the episode of 'buying three nights' in order to recover a spouse is more commonly developed in tales about female heroines who search for their husbands (AT 425, 430, and 432) ..."[10]

- ^ For instance, professor Michael Meraklis commented that despite the general stability of tale type AaTh 403A in Greek variants, the tale sometimes appeared mixed up with tale type AaTh 408, "The Girl in the Citrus Fruit".[11]

- ^ "The motif of a woman stabbed in her head with a pin occurs in AT 403 (in India) and in AT 408 (in the Middle East and southern Europe)."[12]

- ^ As Hungarian-American scholar Linda Dégh put it, "(...) the Orange Maiden (AaTh 408) becomes a princess. She is killed repeatedly by the substitute wife's mother, but returns as a tree, a pot cover, a rosemary, or a dove, from which shape she seven times regains her human shape, as beautiful as she ever was".[14]

References[]

- ^ Giambattista Basile, Pentamerone, "The Three Citrons"

- ^ Steven Swann Jones, The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1995, ISBN 0-8057-0950-9, p. 38.

- ^ Barchilon, Jacques. "Souvenirs et réflexions sur le conte merveilleux". In: Littératures classiques, n°14, janvier 1991. Enfance et littérature au XVIIe siècle. pp. 243-244. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/licla.1991.1282]; www.persee.fr/doc/licla_0992-5279_1991_num_14_1_1282

- ^ "Carnation, White, and Black". In: Quiller-Couch, Arthur Thomas. Fairy tales far and near. London, Paris, Melbourne: Cassell and Company, Limited. 1895. pp. 62-74. [1]

- ^ "Red, White and Black". In: Montalba, Anthony Reubens. Fairy tales from all nations. London: Chapman and Hall, 186, Strand. 1849. pp. 243-246.

- ^ "Roth, weiss und schwarz" In: Kletke, Hermann. Märchensaal: Märchen aller völker für jung und alt. Erster Band. Berlin: C. Reimarus. 1845. pp. 181-183.

- ^ Benovska-Sabkova, Milena. ""Тримата братя и златната ябълка" — анализ на митологическата семантика в сравнителен балкански план ["The three brothers and the golden apple": Analisis of the mythological semantic in comparative Balkan aspect]. In: "Българска етнология" [Bulgarian Ethnology] nr. 1 (1995): 100.

- ^ Dégh, Linda. Narratives in Society: A Performer-Centered Study of Narration. FF Communications 255. Pieksämäki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 1995. p. 41.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6

- ^ Merakles, Michales G. Studien zum griechischen Märchen. Eingeleitet, übers, und bearb. von Walter Puchner. (Raabser Märchen-Reihe, Bd. 9. Wien: Österr. Museum für Volkskunde, 1992. p. 144. ISBN 3-900359-52-0.

- ^ Goldberg, Christine. [Reviewed Work: The New Comparative Method: Structural and Symbolic Analysis of the Allomotifs of "Snow White" by Steven Swann Jones] In: The Journal of American Folklore 106, no. 419 (1993): 106. Accessed June 14, 2021. doi:10.2307/541351.

- ^ Gulyás Judit (2010). "Henszlmann Imre bírálata Arany János Rózsa és Ibolya című művéről". In: Balogh Balázs (főszerk). Ethno-Lore XXVII. Az MTA Neprajzi Kutatóintezetenek évkönyve. Budapest, MTA Neprajzi Kutatóintezete (Sajtó aatt). pp. 250-253.

- ^ Dégh, Linda. American Folklore and the Mass Media. Indiana University Press. 1994. p. 94. ISBN 0-253-20844-0.

- ^ Shojaei-Kawan, Christine (2004). "Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges (AT 408)". In: Folklore (Electronic Journal of Folklore), XXVII, p. 35.

- ^ Angelopoulos, Anna and Kaplanoglou, Marianthi. "Greek Magic Tales: aspects of research in Folklore Studies and Anthropology". In: FF Network. 2013; Vol. 43. p. 15.

- ^ Vikentiev, V. “Le conte égyptien des deux frères et quelques histoires apparentées: La Fille-Citron — La Fille du Marchand — Gilgamesh — Combabus — Localisation du domaine de Bata à Afka — Yamouneh — Les Cèdres”. In: Bulletin of the Faculty of Arts, Fouad I University, Cairo, 11.2 (December 1949). pp. 67–111.

- ^ The Robber with a Witch's Head. Translated by Zipes, Jack. Collected by Laura Gozenbach. Routledge. 2004. p. 217. ISBN 0-415-97069-5.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Dawkins, Richard McGillivray. Modern Greek in Asia Minor: A study of the dialects of Siĺli, Cappadocia and Phárasa, with grammar, texts, translations and glossary. London: Cambridge University Press. 1916. pp. 271-272.

- ^ Shojaei-Kawan, Christine (2004). "Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges (AT 408)". In: Folklore (Electronic Journal of Folklore), XXVII, p. 35.

- ^ Pedroso, Consiglieri. Portuguese Folk-Tales. London: Published for the Folk-Lore Society. 1882. pp. iv.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 94-95. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Delarue, Paul Delarue. The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1956. p. 369.

- ^ Pedrosa, José Manuel. "Cidras y naranjas, o cuentos persas, cuentos españoles y cuentos universales". In: Maryam Haghroosta y José Manuel Pedrosa. Los príncipes convertidos en piedra y otros cuentos tradicionales persas. Guadalajara, España: Palabras del Candil. 2010. pp. 26-39.

- ^ Oriol, Carme. (2015). "Walter Anderson’s Letters to Joan Amades: A Study of the Collaboration between Two Contemporary Folklorists". Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 62 (2015): 150. 10.7592/FEJF2015.62.oriol.

- ^ Dov Neuman (Noy). "Reviewed Work: Typen Tuerkischer Volksmaerchen by Wolfram Eberhard, Pertev Naili Boratav". In: Midwest Folklore 4, no. 4 (1954): 257. Accessed April 12, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4317494.

- ^ Oriol, Carme. (2015). "Walter Anderson’s Letters to Joan Amades: A Study of the Collaboration between Two Contemporary Folklorists". Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 62 (2015): 150. 10.7592/FEJF2015.62.oriol.

- ^ Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. pp. 93–95.

- ^ Cuentos eslovacos de tradición oral. Edición y tradución: Valerica Kovachova, Rivera de Rosales, Bohdan Ulasin, Zuzana Fráterová. Madrid: Ediciones Xorki. 2013. pp. 230-231. ISBN 978-84-940504-0-4.

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales, pp. 737-8. ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Singleton, Esther. The golden rod fairy book. New York, Dodd, Mead & company. 1903. pp. 158-172.

- ^ Zingerle, Ignaz and Josef. Kinder- und Hausmärchen aus Tirol. Innsbruck: Schwick, 1911. pp. 53-58.

- ^ Gonzenbach, Laura. Sicilianische Märchen. Leipzig: Engelmann, 1870. pp. 73-84.

- ^ Gonzenbach, Laura. Sicilianische Märchen. Leipzig: Engelmann, 1870. pp. 73-84.

- ^ Boggs, Ralph Steele; Adams, Nicholson Barney. Spanish Folktales. New York: F. S. Crofts & co., 1932. p. 114.

- ^ Camarena Laucirica, Julio. "Los cuentos tradicionales en Ciudad Real". In: Narria: Estudios de artes y costumbres populares 22 (1981): 37. ISSN 0210-9441.

- ^ Stroebe, Klara; Martens, Frederick Herman. The Norwegian fairy book. New York: Frederick A. Stokes company. [1922.] pp. 16-22

- ^ Cuentos eslovacos de tradición oral. Edición and tradución: Valerica Kovachova, Rivera de Rosales, Bohdan Ulasin, Zuzana Fráterová. Madrid: Ediciones Xorki. 2013. p. 231. ISBN 978-84-940504-0-4.

- ^ Czambel, Samuel. Slovenské ľudové rozprávky. Vol. I. Bratislava: SVKL, 1959. pp. 107-110.

- ^ Strickland, W. W; Erben, Karel Jaromír. Segnius irritant, or Eight primitive folk-lore stories. London: R. Forder. 1896. pp. 38-47.

- ^ Strickland, W. W; Erben, Karel Jaromír. Segnius irritant, or Eight primitive folk-lore stories. London: R. Forder. 1896. pp. 48-53.

- ^ Fillmore, Parker. Czechoslovak Fairy Tales. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. 1919. pp. 55-76.

- ^ Valjavec, Matija Kračmanov. Narodne pripovjedke u i oko Varaždina. 1858. pp. 212-214.

- ^ Zečević, Divna. "USMENA KAZIVANJA U OKOLICI DARUVARA" [ORAL NARRATIVE IN THE SURROUNDING OF DARUVAR]. In: Narodna umjetnost 7, br. 1 (1970): 61-63, 67. https://hrcak.srce.hr/39258

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. "A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus". In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 234. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Petrów, Aleksander (1878). Lud ziemi dobrzyńskiej, jego zwyczaje, mowa, obrzędy, pieśni, leki, zagadki, przysłowia itp. Krakow: Uniwersytet Jagielloński. pp. 142-144.

- ^ Ciszewski, Stanisław. Krakowiacy: Monografja etnograficzna. Tom I. Krakow: 1894. pp. 58–60.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. "Indexing Folktales: A Critical Survey". In: Journal of Folklore Research 34, no. 3 (1997): 213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3814887.

- ^ Arnold Ipolyi. Ipolyi Arnold népmesegyüjteménye (Népköltési gyüjtemény 13. kötet). Budapest: az Athenaeum Részvénytársulat Tulajdona. 1914. p. 521.

- ^ VASVÁRI Zoltán. "Népmese a Palócföldön". In: Palócföld 1999/2, pp. 93-94.

- ^ Merényi László. Eredeti Népmesék. Masódik Rész. Pest: Kiadja Heckenast Gusztáv. 1861. pp. 35-64.

- ^ Curtin, Jeremiah. Myths and Folk-tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1890. pp. 457-476.

- ^ Sklarek, Elisabet. Ungarische Volksmärchen. Einl. A. Schullerus. Leipzig: Dieterich 1901. pp. 74-79.

- ^ Antal Horger. Hétfalusi csángó népmesék (Népköltési gyüjtemény 10. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvénytársulat Tulajdona. 1908. pp. 96-103.

- ^ Antal Horger. Hétfalusi csángó népmesék (Népköltési gyüjtemény 10. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvénytársulat Tulajdona. 1908. p. 456.

- ^ Stier, G. Ungarische Sagen und Märchen. Berlin: Ferdinand Dümmlers Buchhandlung, 1850. pp. 83-91.

- ^ Jones, W. Henry; Kropf, Lajos L.; Kriza, János. The folk-tales of the Magyars. London: Pub. for the Folk-lore society by E. Stock. 1889. pp. 133-136.

- ^ János Berze Nagy. Népmesék Heves- és Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok-megyébol (Népköltési gyüjtemény 9. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvény-Társulát Tulajdona. 1907. pp. 213-216.

- ^ Wratislaw, A. H. Sixty Folk-Tales from Exclusively Slavonic Sources. London: Elliot Stock. 1889. pp. 63-74.

- ^ Rimauski, Johann. Slovenskje povesti [Slovakische Erzählungen]. Zvazok I. V Levoci: u Jana Werthmüller a sina. 1845. pp. 37-52.

- ^ Klimo, Michel. Contes et légendes de Hongrie. Les littératures populaires de toutes les nations. Traditions, légendes, contes, chansons, proverbes, devinettes, superstitïons. Tome XXXVI. Paris: J. Maisonneuve. 1898. pp. 154-160.

- ^ Bálint Péter. Archaikus Alakzatok A Népmesében. Jakab István cigány mesemondó (a késleltető halmozás mestere) [Archaic Images in Folk Tales. The Tales of István Jakab, Gypsy Tale Teller (the master of delayed accumulation)]. Debrecen: 2014. pp. 246 (footnore nr. 3) and 255. ISBN 978-615-5212-19-2.

- ^ Elek Benedek. Magyar mese- és mondavilág II. Budapest: Könyvértékesítő Vállalat-Móra Ferenc Ifjúsági Könyvkiadó. 1988. pp. 28-31.

- ^ Arnold Ipolyi. Ipolyi Arnold népmesegyüjteménye (Népköltési gyüjtemény 13. kötet). Budapest: az Athenaeum Részvénytársulat Tulajdona. 1914. pp. 297-301.

- ^ Frankovics György. A bűvös puska. Budapest: Móra Könyvkiadó. 2015. pp. 86-90.

- ^ Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1-2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. pp. 244-250.

- ^ Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1-2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. pp. 404.

- ^ Sandu Timoc, Cristea. Poveşti populare româneşti. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1988. p. viii.

- ^ Schott, Arthur und Albert. Rumänische Volkserzählungen aus dem Banat. Bukarest: Kriterion. 1975. pp. 188-194.

- ^ Ispirescu, Petre. Roumanian folk tales. Retold from the original by Jacob Bernard Segall. Orono, Me.: Printed at the University Press, 1925. pp. 11ff (Tale nr. 1).

- ^ Benovska-Sabkova, Milena. ""Тримата братя и златната ябълка" — анализ на митологическата семантика в сравнителен балкански план ["The three brothers and the golden apple": Analisis of the mythological semantic in comparative Balkan aspect]. In: "Българска етнология" [Bulgarian Ethnology] nr. 1 (1995): 100.

- ^ Puchner, Walter. "Argyrō Xenophōntos, Kōnstantina Kōnstantinou (eds.): Ta paramythia tēs Kyprou apo to Laographiko Archeio tou Kentrou Epistemonikōn Ereunōn 2015 [compte-rendu]". In: Fabula 57, no. 1-2 (2016): 188-190. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabula-2016-0032

- ^ Stumme, Hans. Maltesische Märchen, Gedichte und Rätsel in deutscher Übersetzung. Leipziger Semitistische Studien, Band 1, Heft 5, Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichsche Buchhandlung, 1904. pp. 71-76.

- ^ Stroebe, Klara; Martens, Frederick Herman. The Norwegian fairy book. New York: Frederick A. Stokes company. [1922.] p. 22.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich; van Leewen, Richard. The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. Vol. I. California: ABC-Clio. 2004. p. 12. ISBN 1-85109-640-X (e-book)

- ^ El-Shamy, Hasan (2004). Types of the Folktale in the Arab World: A Demographically Oriented Tale-Type Index. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 195-196.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich. Typologie des persischen Volksmärchens. Beirut: Orient-Inst. der Deutschen Morgenländischen Ges.; Wiesbaden: Steiner [in Komm.], 1984. pp. 79-82.

- ^ Pyle, Katherine. Tales of folk and fairies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1919. pp. 180-200.

- ^ Lorimer, David Lockhart Robertson; Lorimer, Emily Overend. Persian tales. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd. 1919. pp. 135-147.

- ^ Koçak Macun, Büşra. (2016). "Erzurum Halk Masallarından Üç Turunçlar Masalı'nın Vladimir Propp'un Yapısal Anl" [Investigation of Fairy Tale Name is Three Sour Oranges That is Folk Tale from Erzurum by Using Vladimir Propper’s Structural Narrative Analysis Methods]. In: Turkish Studies volume 11., issue 15 (Summer/2016): 327-346. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.9542

- ^ Dov Neuman (Noy). "Reviewed Work: Typen Tuerkischer Volksmaerchen by Wolfram Eberhard, Pertev Naili Boratav". In: Midwest Folklore 4, no. 4 (1954): 257. Accessed April 12, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4317494.

- ^ Kúnos, Ignácz. Turkish fairy tales and folk tales collected by Dr. Ignácz Kúnos. London, Lawrence and Bullen. 1896. pp. 12-30.

- ^ Johnson, Clifton. The fir-tree fairy book; favorite fairy tales. Boston: Little, Brown. 1912. pp. 158-172.

- ^ Günay Türkeç, U. (2009). "Türk Masallarında Geleneksel ve Efsanevi Yaratıklar" [Traditional and Legendary Creatures in Turkish Tales]. In: Motif Akademi Halkbilimi Dergisi, 2 (3-4): 92-93. Retrieved from [2]

- ^ Dracott, Alice Elizabeth. Simla Village Tales, or Folk Tales from the Himalayas. England, London: John Murray. 1906. pp. 226-237.

- ^ Stokes, Maive. Indian fairy tales, collected and tr. by M. Stokes; with notes by Mary Stokes. London: Ellis and White. 1880. pp. 138-152.

- ^ Bompas, Cecil Henry. Folklore of the Santal Parganas. London: David Nutt. 1909. pp. 461-464.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard McGillivray. Modern Greek in Asia Minor: A study of the dialects of Siĺli, Cappadocia and Phárasa, with grammar, texts, translations and glossary. London: Cambridge University Press. 1916. p. 272.

- ^ Jason, Heda. "India on the Map of 'Hard Science' Folkloristics". In: Folklore 94, no. 1 (1983): 106. Accessed April 12, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1260173.

- ^ Takagi Masafumi. "[シリーズ/比較民話(一)瓜子姫/三つのオレンジ]" [Series: Comparative Studies of the Folktale (1) Melon Princess/The Three Oranges]. In: The Seijo Bungei: the Seijo University arts and literature quarterly 222 (2013-03). p. 45-64.

- ^ Takagi Masafumi. "[シリーズ/比較民話(一)瓜子姫/三つのオレンジ]" [Series: Comparative Studies of the Folktale (1) Melon Princess/The Three Oranges]. In: The Seijo Bungei: the Seijo University arts and literature quarterly 222 (2013-03). p. 51.

- ^ Shojaei-Kawan, Christine (2004). "Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges (AT 408)". In: Folklore (Electronic Journal of Folklore), XXVII, p. 39.

- ^ The Junior Classics, Volume 2: Folk Tales and Myths. Selected and arranged by William Patten. New York: P. F. Collier and Son. 1912. pp. 500-511.

- ^ Nogués, Romualdo. Cuentos para gente menuda. segunda Edición. Madrid: Imprenta de A. Pérez Dubrull. 1887. pp. 36-45. [3]

- ^ Republished in: Bolisek, Ran. "Неродена мома. Незнаен юнак. Жива вода. Народни приказки". Sofia: Издателство народна младеж. 1978. Tale nr. 1.

Bibliography[]

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Zweiter Band (NR. 61-120). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. p. 125 (footnote nr. 2).

- Oriol, Carme (2015). "Walter Anderson’s Letters to Joan Amades: A Study of the Collaboration between Two Contemporary Folklorists". Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 62 (2015): 139–174. 10.7592/FEJF2015.62.oriol.

- Shojaei-Kawan, Christine (2004). "Reflections on International Narrative Research on the Example of the Tale of the Three Oranges (AT 408)". In: Folklore (Electronic Journal of Folklore), XXVII, pp. 29–48.

Further reading[]

- Cardigos, Isabel. "Review [Reviewed Work: The Tale of the Three Oranges by Christine Goldberg]" Marvels & Tales 13, no. 1 (1999): 108–11. Accessed June 20, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41388536.

- Da Silva, Francisco Vaz. "Red as Blood, White as Snow, Black as Crow: Chromatic Symbolism of Womanhood in Fairy Tales." Marvels & Tales 21, no. 2 (2007): 240–52. Accessed June 20, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41388837.

- Gobrecht, Barbara. "Auf den Spuren der Zitronenfee: eine Märchenreise. Der Erzähltyp 'Die drei Orangen’ (ATU 408)“. In: Märchenspiegel. 17. Jahrgang. November 2006. pp. 14-30.

- Hemming, Jessica. "Red, White, and Black in Symbolic Thought: The Tricolour Folk Motif, Colour Naming, and Trichromatic Vision." Folklore 123, no. 3 (2012): 310–29. Accessed June 20, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41721562.

- 剣持 弘子 [Kendo, Hiroko].「瓜子姫」 —話型分析及び「三つのオレンジ」との関係— ("Urikohime": Analysis and Relation with "Three Oranges"). In: 『口承文芸研究』nr. 11 (March, 1988). pp. 45-57.

- Mazzoni, Cristina. "The Fruit of Love in Giambattista Basile's “The Three Citrons”." Marvels & Tales 29, no. 2 (2015): 228-44. Accessed June 20, 2020. doi:10.13110/marvelstales.29.2.0228.

- Prince, Martha. "The love for three oranges (Aarne-Thompson Tale Type 408): A study in traditional variation and literary adaptation." Electronic Thesis or Dissertation. Ohio State University, 1962. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/

External links[]

- The Three Citrons, on Laboulaye's Fairy Book

- Italian fairy tales

- Fiction about shapeshifting

- Stories within Italian Folktales

- Recurrent elements in fairy tales

- Fruit