The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird

| The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird | |

|---|---|

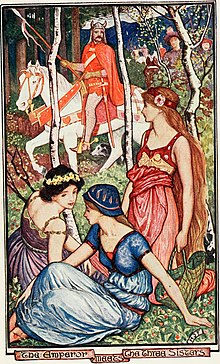

The foster mother (doe) looks after the wonder-children. Artwork by John D. Batten for Jacobs's Europa's Fairy Book (1916). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird |

| Data | |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 707 (The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird; The Bird of Truth; The Three Golden Children; The Three Golden Sons) |

| Region | Sicily, Eurasia, Worldwide |

| Related | Ancilotto, King of Provino; Princess Belle-Étoile and Prince Chéri; The Tale of Tsar Saltan; The Boys with the Golden Stars |

The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird is a Sicilian fairy tale collected by Giuseppe Pitrè,[1] and translated by Thomas Frederick Crane for his Italian Popular Tales.[2] Joseph Jacobs included a reconstruction of the story in his European Folk and Fairy Tales.[3] The original title is "Li Figghi di lu Cavuliciddaru", for which Crane gives a literal translation of "The Herb-gatherer's Daughters."[4]

The story is the prototypical example of Aarne–Thompson–Uther tale-type 707, to which it gives its name.[5] Alternate names for the tale type are The Three Golden Sons, The Three Golden Children, The Bird of Truth, Portuguese: Os meninos com uma estrelinha na testa, lit. 'The boys with little stars on their foreheads',[6] Russian: Чудесные дети, romanized: Chudesnyye deti, lit. 'The Wonderful or Miraculous Children',[7] or Hungarian: Az aranyhajú ikrek, lit. 'The Golden-Haired Twins'.[8]

According to folklorist Stith Thompson, the tale is "one of the eight or ten best known plots in the world".[9]

Synopsis[]

The following is a summary of the tale as it was collected by Giuseppe Pitrè and translated by Thomas Frederick Crane.

A king walking the streets heard three poor sisters talk. The oldest said that if she married the royal butler, she would give the entire court a drink out of one glass, with water left over. The second said that if she married the keeper of the royal wardrobe, she would dress the entire court in one piece of cloth, and have some left over. The youngest said that if she married the king, she would bear two sons with apples in their hands, and a daughter with a star on her forehead.

The next morning, the king ordered the older two sisters to do as they said, and then married them to the butler and the keeper of the royal wardrobe, and the youngest to himself. The queen became pregnant, and the king had to go to war, leaving behind news that he was to hear of the birth of his children. The queen gave birth to the children she had promised, but her sisters, jealous, put three puppies in their place, sent word to the king, and handed over the children to be abandoned. The king ordered that his wife be put in a treadwheel crane.

Three fairies saw the abandoned children and gave them a deer to nurse them, a purse full of money, and a ring that changed color when misfortune befell one of them. When they were grown, they left for the city and took a house.

Their aunts saw them and were terror-struck. They sent their nurse to visit the daughter and tell her that the house needed the Dancing Water to be perfect and her brothers should get it for her. The oldest son left and found three hermits in turn. The first two could not help him, but the third told him how to retrieve the Dancing Water, and he brought it back to the house. On seeing it, the aunts sent their nurse to tell the girl that the house needed the Singing Apple as well, but the brother got it, as he had the Dancing Water. The third time, they sent him after the Speaking Bird, but as one of the conditions was that he not respond to the bird, and it told him that his aunts were trying to kill him and his mother was in the treadmill, it shocked him into speech, and he was turned to stone. The ring changed colors. His brother came after him, but suffered the same fate. Their sister came after them both, said nothing, and transformed her brother and many other statues back to life.

They returned home, and the king saw them and thought that if he did not know his wife had given birth to three puppies, he would think these his children. They invited him to dinner, and the Speaking Bird told the king all that had happened. The king executed the aunts and their nurse and took his wife and children back to the palace.

Overview[]

The following summary was based on Joseph Jacobs's tale reconstruction in his Europa's Fairy Book, on the general analyses made by Arthur Bernard Cook in his Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion,[10] and on the description of the tale-type in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index classification of folk and fairy tales.[11] This type follows an almost fixed structure, with very similar characteristics, regardless of their geographic distribution:[10]

The king passes by a house or other place where three sisters are gossiping or talking, and the youngest says, if the king married her, she would bear him "wondrous children"[12] (their peculiar appearances tend to vary, but they are usually connected with astronomical motifs on some part of their bodies, such as the Sun, the moon or stars). The king overhears their talk and marries the youngest sister, to the envy of the older ones or to the chagrin of the grandmother. As such, the jealous relatives deprive the mother of her newborn children (in some tales, twins[a] or triplets, or three consecutive births, but the boy is usually the firstborn, and the girl is the youngest),[14] either by replacing the children with animals or accusing the mother of having devoured them. Their mother is banished from the kingdom or severely punished (imprisoned in the dungeon or in a cage; walled in; buried up to the torso). Meanwhile, the children are either hidden by a servant of the castle (gardener, cook, butcher) or cast into the water, but they are found and brought up at a distance from the father's home by a childless foster family (fisherman, miller, etc.).[15]

Years later, after they reach a certain age, a magical helper (a fairy, or the Virgin Mary in more religious variants) gives them means to survive in the world. Soon enough, the children move next to the palace where the king lives, and either the aunts, or grandmother realize their nephews/grandchildren are alive and send the midwife (or a maid; a witch; a slave) or disguise themselves to tell the sister that her house needs some marvellous items, and incite the girl to convince her brother(s) to embark on the (perilous) quest. The items also tend to vary, but in many versions there are three treasures: (1) water, or some water source (e.g., spring, fountain, sea, stream) with fantastic properties (e.g., a golden fountain, or a rejuvenating liquid); (2) a magical tree (or branch, or bough, or flower, or a fruit – usually apples) with strange powers (e.g., makes music or sings); and (3) a wondrous bird that can tell the truth, knows many languages and/or turns people to stone.[b][full citation needed][c]

The brother(s) set(s) off on his (their) journey, but give(s) a token to the sister so she knows the brother(s) is(are) alive. Eventually, the brothers meet a character (a sage, an ogre, etc.) that warns them not to listen to the bird, otherwise he will be petrified (or turned to salt, or to marble pillars). The first brother fails the quest, and so does the next one. The sister, seeing that the tokens changed colour, realizes her siblings are in danger and departs to finish the quest for the wonderful items and rescue her brother(s).

Afterwards, either the siblings invite the king or the king invites the brothers and their sister for a feast in the palace. As per the bird's instructions, the siblings display their etiquette during the meal (in some versions, they make a suggestion to invite the disgraced queen; in others, they give their poisoned meal to some dogs). Then, the bird reveals the whole truth, the children are reunited with their parents, and the jealous relatives are punished.

Variations[]

While the formula is almost followed to the letter, some variations occur in the second part of the story (the quest for the magical items), and even in the conclusion of the tale. Folklore scholar Christine Goldberg identifies three main forms of the tale type: a variation found "throughout Europe", with the quest for the items; "an East Slavic form", where mother and son are cast in a barrel and later the sons build a palace; and a third one, where the sons are buried and go through a transformation sequence, from trees to animals to humans again.[17]

The Brother Quests for a Bride[]

In some tales, when the sister is lured by the antagonist's agent, she is told to look for the belongings (mirror, flower, handkerchief) of a woman of unearthly beauty or a fairy. Such variants occur in Albania, as in the tales collected by J. G. Von Hahn in his Griechische und Albanische Märchen (Leipzig, 1864), in the village of Zagori in Epirus,[18] and by Auguste Dozon in Contes Albanais (Paris, 1881). These stories substitute the quest for the items for the search for a fairy named E Bukura e Dheut ("Beauty of the Land"), a woman of extraordinary beauty and magical powers.[19][20] One such tale is present in Robert Elsie's collection of Albanian folktales (Albania's Folktales and Legends): The Youth and the Maiden with Stars on their Foreheads and Crescents on their Breasts.[21][22]

Another version of the story is The Tale of Arab-Zandyq,[23][24] in which the brother is the hero who gathers the wonderful objects (a magical flower and a mirror) and their owner (Arab-Zandyq), whom he later marries. Arab-Zandyq replaces the bird and, as such, tells the whole truth during her wedding banquet.[25][26]

In a specific Armenian variant, called The Twins, the last quest for the brother is to find the daughter of an Indian king and bring her to his king's palace. In this version, it is a king who overhears the sisters' nightly conversation in his search for a wife for his son. At the end, the brother marries the foreign princess and his sister reveals the truth to the court.[27]

This conclusion also happens in an Indian variant, called The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead, from Bengali. In this tale, the queen begets the wonder-children (fraternal twins, a girl and a boy); the antagonists are the other six queens, who, overcome with jealousy, trick the new queen with puppies and expose the children. When they both grow up, the jealous queens set the siblings on a quest for a kataki flower, with the brother rescuing Lady Pushpavati from Rakshasas. Lady Pushpavati marries the titular "boy with the moon on his forehead" and reveals to the King her mother-in-law's ordeal and the deceit of the King's co-wives.[28]

In an extended version from a Breton source, called L'Oiseau de Vérité,[29] the youngest triplet, a king's son, listens to the helper (an old woman), who reveals herself to be a princess enchanted by her godmother. In a surprise appearance by said godmother, she prophecises her goddaughter shall marry the hero of the tale (the youngest prince), after a war with another country.

Another motif that appears in these variants (specially in Middle East and Turkey) is suckling an ogress's breastmilk by the hero.[30]

The Sister marries a Prince[]

In an Icelandic variant collected by Jón Árnason and translated in his book Icelandic Legends (1866), with the name Bóndadæturnar (The Story of the Farmer's Three Daughters, or its German translation, Die Bauerntöchter),[31] the quest focus on the search for the bird and omits the other two items. The end is very much the same, with the nameless sister rescuing her brothers Vilhjámr and Sigurdr and a prince from the petrification spell and later marrying him.[32]

Another variant where this happy ending occurs is Princesse Belle-Étoile et Prince Chéri, by Mme. D'Aulnoy, where the heroine rescues her cousin, Prince Chéri, and marries him. Another French variant, collected by (L'Arbre qui chante, l'Oiseau qui parle et l'Eau d'or, or "The tree that sings, the bird that speaks and the water of gold"), has the youngest daughter, the princess, marry an enchanted old man she meets in her journey and who gives her advice on how to obtain the items.[33]

In a tale collected in Carinthia (Kärnten), Austria (Die schwarzen und die weißen Steine, or "The black and white stones"), the three siblings climb a mountain or slope, but the brothers listen to the sounds of the mountain and are petrified. Their sister arrives at a field of white and black stones and, after a bird gives her instructions, sprinkles magic water on the stones, restoring her brothers and many others – among them, a young man, whom she later marries.[34]

In the Armenian variant Théodore, le Danseur, the brother ventures on a quest for the belongings of the eponymous character and, at the conclusion of the tale, this fabled male dancer marries the sister.[35][36]

In The Three Little Birds, a folktale collected by the Brothers Grimm, in Kinder- und Hausmärchen (KHM nr. 96), instructed by an old woman fishing, the sister strikes a black dog and it transforms into a prince, with whom she marries as the truth settles among the family.

A similar conclusion happens in the commedia dell'arte The Green Bird, where the brother undergoes the quest for the items, and the titular green bird is a cursed prince, who, after being released from its avian form, marries the sister.

The Tale of Tsar Saltan[]

Some versions of the tale have the mother being cast out with the babies into the sea in a box, after the king is tricked into thinking his wife did not deliver her promised wonder children. The box eventually washes ashore on the beaches of an island or another country. There, the child (or children) magically grows up in hours or days and builds an enchanted castle or house that attracts the attention of the common folk (or merchants, or travellers). Word reaches the ears of the despondent king, who hears about the mysterious owners of such fantastic abode, who just happen to look like the children he would have had.

French scholar Gédeon Huet considered this format as "the Slavic version" of Les soeurs jalouses and suggested that this format "penetrated into Siberia", brought by Russian migrants.[37]

This "Slavic" narrative (mother and child or children cast into a chest) recalls the motif of "The Floating Chest", which appears in narratives of Greek mythology about the legendary birth of heroes and gods.[38][39] The motif also appears in the Breton legend of saint Budoc and his mother Azénor: Azénor was still pregnant when cast into the sea in a box by her husband, but an angel led her to safety and she gave birth to future Breton saint Budoc.[40]

Russian tale collections attest to the presence of Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore, as the antagonist in many of the stories.[41]

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva suggests that this format must have developed during the period of the Kievan Rus, a period where an intense fluvial trade network developed, since this "East Slavic format" emphasizes the presence of foreign merchants and traders. She also argues for the presence of the strange island full of marvels as another element.[42]

Rescue of brothers from transformation[]

In some variants of this format, the castaway boy sets a trap to rescue his brothers and release them from a transformation curse. For example, in Nád Péter ("Schilf-Peter"), a Hungarian variant,[43] when the hero of the tale sees a flock of eleven swans flying, he recognizes them as their brothers, who have been transformed into birds due to divine intervention by Christ and St. Peter.

In another format, the boy asks his mother to prepare a meal with her "breast milk" and prepares to invade his brothers' residence to confirm if they are indeed his siblings. This plot happens in a Finnish variant, from Ingermanland, collected in Finnische und Estnische Volksmärchen (Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne, or "Brother and Sister, and the golden-haired sons of the King").[44] The mother gives birth to six sons with special traits who are sold to a devil by the old midwife. Some time later, their youngest brother enters the devil's residence and succeeds in rescuing his siblings.

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva argues that the use of "mother's milk" or "breast milk" as the key to the reversal of the transformation can be explained by the ancient belief that it has curse-breaking properties.[42] Likewise, scholarship points to an old belief connecting breastmilk and "natal blood", as observed in the works of Aristotle and Galen. Thus, the use of mother's milk serves to reinforce the hero's blood relation with his brothers.[45] Professor Khemlet Tatiana Yurievna describes that this is the version of the tale type in East Slavic, Scandinavian and Baltic variants.[46]

The Boys With The Golden Stars[]

The motif of a woman's babies, born with wonderful attributes after she claimed she could bear such children, but stolen from her, is a common fairy tale motif. In this plot-type, an evil stepmother (or grandmother, or gypsy, or slave, or maid) kills the babies, but the twins go through a resurrective reincarnation: from trees to animals and finally into humans babies again. This transformation chase where the stepmother is unable to prevent the children's reappearance is unusual, although it appears in "A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers" and in "The Count's Evil Mother", a Croatian tale from the Karlovac area.[47]

Most versions of The Boys With Golden Stars[48] begin with the birth of male twins, but very rarely there are fraternal twins, a boy and a girl. When they transform into human babies again, the siblings grow up at an impossibly fast rate and hide their supernatural trait under a hood or a cap. Soon after, they show up in their father's court or house to reveal the truth through a riddle or through a ballad.

This tale's format happens in many variants collected in the Balkan area, specially in Romenia,[49][50] as it can be seen in The Boys with the Golden Stars (Romanian: Doi feți cu stea în frunte) collected in Rumänische Märchen,[51] which Andrew Lang included in his The Violet Fairy Book.[52]

The format of the story The Boys With The Golden Stars seems to concentrate around Eastern Europe: in Romania;[49][50][53][54][55][56][57] a version in Belarus;[58] in Serbia;[59][60] in the Bukovina region;[61] in Croatia;[62][63] Bosnia,[64] Moldavia,[65] Bulgaria,[66] Poland, Ukraine, Czech Republic, Slovakia,[67][68][69] and among the Transylvanian Saxons.[70]

Hungarian scholar Ágnes Kovács stated that this was the "Eastern European subtype" of the tale Cei doi fraţi cu păr de aur ("The Twin Brothers With Golden Hair"), found "all across the Romanian language territories", as well in Hungarian speaking regions.[71]

Writer and folklorist Cristea Sandu Timoc considered that these tales were typically Romanian, and belonged to tale type AaTh 707C*. He also reported that "more than 70 variants" of this subtype were "known" (as of 1988).[72]

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva names this format "Reincarnation of the Luminous Twins" and considers this group of variants as "an ancient Slavic plot", since these tales have been collected from Slavic-speaking areas.[73] Another argument she raises is that the tree transformation in most variants is the sycamore, a tree with mythical properties in East Slavic folklore.[74] She also argues that this format is the "archaic version" of the tale type, since it shows the motif of the tree and animal transformation, and recalls ancient ideas of twin beings in folklore.[75]

On the other hand, according to researcher Maxim Fomin, Irish folklorist Seán Ó Súilleabháin identified a second ecotype (oikotype) of type ATU 707 in Ireland, which corresponds to the birth of the miraculous twins, their death by burial, and the cycle of transformations from plant to animal to humans again.[76]

Similarly, Lithuanian scholarship (namely, Bronislava Kerbelytė (lt) and Daiva Vaitkevičienė) lists at least 23 variants of this format in Lithuania. In these variants, the youngest sister promises to give birth to twins with the sun on the forehead, the moon on the neck and stars on the temples. A boy and a girl are born, but they are buried by a witch, and on their graves an apple tree and a pear tree sprout. They mostly follow the cycle of transformations (from human babies, to trees, to animals and finally to humans again), but some differ in that after they become lambs, they are killed and their ashes are eaten by a duck that hatches two eggs.[77]

Alternate Source for the Truth to the King (Father)[]

In a Kaba'il version from Northern Algeria (Les enfants et la chauve-souris),[78] the bird is replaced by a bat, who helps the abandoned children when their father takes them back and his second wife prepares them a poisoned meal. The bat recommends the siblings to give their meal to animals, in order to prove it's poisoned and to reveal the treachery of the second wife.[79][need quotation to verify]

In a specific folktale from Egypt, El-Schater Mouhammed,[80] the Brother is the hero of the story, but the last item of the quest (the bird) is replaced by "a baby or infant who can speak eloquently", as an impossible MacGuffin. The fairy (or mystical woman) he sought before gives both siblings instructions to summon the being in front of the king, during a banquet.

In many widespread variants, the bird is replaced by a fairy or magical woman the Brother seeks after as part of the impossible tasks set by his aunts, and whom he later marries (The Brother Quests for a Bride format).[81]

Very rarely, it is one of the children themselves that reveal the aunts' treachery to their father, as seen in the Armenian variants The Twins and Theodore, le Danseur.[35][36] In a specific Persian version, from Kamani, the Prince (King's son) investigates the mystery of the twins and questions the midwife who helped in the delivery of his children.[82]

Motifs[]

According to Daniel Aranda, the tale type develops the narrative in two eras: the tale of the calumniated wife as the first; and the adventures of the children as the second, wherein the mother becomes the object of their quest.[83]

The Persecuted Wife and Jealous Sisters[]

Ethnologist Verrier Elwin commented that the motif of jealous queens, instead of jealous sisters, is present in a polygamous context: the queens replace the youngest queen's child (children) with animals or objects and accuse the woman of infidelity. The queen is then banished and forced to work in a humiliating job.[84]

In the same vein, French ethnologue Paul Ottino (fr), by analysing similar tales from Madagascar, concluded that the jealousy of the older co-wives of the polygamous marriage motivate their attempt on the children, and, after the children are restored, the co-wives are duly punished, paving the way for a monogamous family unit with the expelled queen.[85]

The Wonder Children[]

The story of the birth of the wonderful children can be found in Medieval author Johannes de Alta Silva's Dolopathos sive de Rege et Septem Sapientibus (c. 1190), a Latin version of the Seven Sages of Rome.[86] The tale was adapted into the French Li romans de Dolopathos by the poet Herbert.[87] Dolopathos also comprises the Knight of the Swan cycle of stories. This version of the tale preserves the motif of the wonder-children, which are born "with golden chains around their necks", the substitution for animals and the degradation of the mother, but merges with the fairy tale The Six Swans, where brothers transformed into birds are rescued by the efforts of their sister,[88] which is Aarne-Thompson 451, "The boys or brothers transformed into birds".

In a brief summary:[86][89] a lord encounters a mysterious woman (clearly a swan maiden or fairy) in the act of bathing, while clutching a gold necklace, they marry and she gives birth to a septuplet, six boys and a girl, with golden chains about their necks. But her evil mother-in-law swaps the newborn with seven puppies. The servant with orders to kill the children in the forest just abandons them under a tree. The young lord is told by his wicked mother that his bride gave birth to a litter of pups, and he punishes her by burying her up to the neck for seven years. Some time later, the young lord while hunting encounters the children in the forest, and the wicked mother's lie starts to unravel. The servant is sent out to search them, and finds the boys bathing in the form of swans, with their sister guarding their gold chains. The servant steals the boys' chains, preventing them from changing back to human form, and the chains are taken to a goldsmith to be melted down to make a goblet. The swan-boys land in the young lord's pond, and their sister, who can still transform back and forth into human shape by the magic of her chain, goes to the castle to obtain bread to her brothers. Eventually the young lord asks her story so the truth comes out. The goldsmith was actually unable to melt down the chains, and had kept them for himself. These are now restored back to the six boys, and they regain their powers, except one, whose chain the smith had damaged in the attempt. So he alone is stuck in swan form. The work goes on to say obliquely hints that this is the swan in the Swan Knight tale, more precisely, that this was the swan "quod cathena aurea militem in navicula trahat armatum (that tugged by a gold chain an armed knight in a boat)."[86]

The motif of the heroine persecuted by the queen, on false pretenses, also happens in Istoria della Regina Stella e Mattabruna,[90] a rhyming story of the ATU 706 type (The Maiden Without Hands).[91]

India-born author Maive Stokes suggested, in her notes to the Indian version she collected, that the motif of the children's "silver chains (sic)" of the Dolopathos tale was parallel to the astronomical motifs on the children's bodies.[92]

Fate of the Wonder Children[]

When the jealous sisters or jealous co-wives replace the royal children for animals and objects, they either bury the children in the garden (the twins become trees) in some variants, or put the siblings in a box and cast it into the water (river, stream).[84] French ethnologue Paul Ottino (fr) noted that the motif of casting the children in the water vaguely resembles the Biblical story of Moses, but, in these stories, the children are cast in a box in order to perish in the dangerous waters.[93]

After the stepmother or queen's sisters abandon the babies in the forest, in several variants the twins or triplets are reared by a wild animal. This episode recalls similar mythological stories about half-human, half-divine sons abandoned in the woods and suckled by a female animal. Such stories have been dramatized in Ancient Greek plays of Euripides and Sophocles.[94] This episode also happens in myths about the childhood of some gods (e.g, Zeus and fairy or she-goat Amalthea, Telephus, Dionysus). Professor Giulia Pedrucci suggests that the unusual breastfeeding by the female animal (i.e., by a cow, a hind, a deer, a she-wolf) sets the hero apart from the "normal" and "civilized" world and puts them on a road to achieve a great destiny, since many of these heroes and gods become founders of dynasties and/or kings.[95]

Astronomical signs on bodies[]

The motif of the children born with astronomical signs on their bodies appears in Russian fairy tales and healing incantations,[7] with the formula "a red star or sun in the front, a moon on the back of the neck and a body covered with stars". A similar imagery appears in Lithuanian fairy tales, with the queen giving birth to her children with solar/lunar/astral birthmarks.[96][97][98][d] However, Western scholars interpret the motif as a sign of royalty.[100]

India-born author Maive Stokes, as commented by Joseph Jacobs, noted that the motif of children born with stars, moon or a sun in some part of their bodies occurred to heroes and heroines of both Asian and European fairy tales,[101] and are by no means restricted to the ATU 707 tale type.

Lithuanian scholarship (e.g., Norbertas Vėlius) suggests that the character of the maiden with astronomical motifs on her head (sun, moon and/or star) may be reflective of the Baltic Morning Star character Aušrinė.[102][103][104]

In the same vein, Russian professor Khemlet Tat'yana Yur'evna suggests that the presence of the astronomical motifs on the children's bodies possibly refer to their connection to a celestial or heavenly realm. She also argues that similar motifs (golden chains, body parts shining like gold and/or silver, golden hair and silver hair) are a reminiscence or vestige of the solar/lunar/astral motif (which corresponds to the oldest layer). Finally, tales of later tradition that lack either one of these motifs replace them with special attributes or names to the children, like the Brother being a mighty hero and the Sister being a skilled weaver.[105] In a later study, Khemlet argues that variants of later tradition gradually lose the fantasy elements and a more realistic narrative emerges, with the fantastical becoming unreal and with more develoment of the characters' psychological state.[106]

The Dancing Water[]

Folklorist Christine Goldberg, in the entry of the tale type in Enzyklopädie des Märchens, concluded that historical and geographical evidence led her to believe that the quest for the treasures was a later development of the narrative, inserted into the tale type.[107]

Scholars have proposed that the quest for the Dancing Water in these tales are part of a macrocosm of similar tales about the quest for a Water of Life or Fountain of Immortality.[108] Czech scholar Jaromir Jech (cs) remarked that, in this tale type, after the heroine quests for the speaking bird, the singing tree and the water of life, she uses the water as remedy to restore her brothers after they are petrified for failing the quest.[109]

In regards to Lithuanian variants where the object of the quest is the "yellow water" or "golden water", Lithuanian scholarship suggests that the color of the water evokes a sun or dawn motif.[110]

The reincarnation motif in The Boys with The Golden Stars format[]

Daiva Vaitkevičienė suggested that the transformation sequence in the tale format (from human babies, to trees, to lambs/goats and finally to humans again) may be underlying a theme of reincarnation, metempsychosis or related to a life-death-rebirth cycle.[111] This motif is shared by other tale types, and does not belong exclusively to the ATU 707.

A similar occurrence of the tree reincarnation is attested in the Bengal folktale The Seven Brothers who were turned into Champa Trees[112] (Sat Bhai Chompa, first published in 1907)[113] and in the tale The Real Mother, collected in Simla.[114]

India-born author Maive Stokes noted the resurrective motif of the murdered children, and found parallels among European tales published during that time.[115] Austrian consul Johann Georg von Hahn also remarked on a similar transformation sequence present in a Greek tale from Asia Minor, Die Zederzitrone, a variant of The Love for Three Oranges (ATU 408).[116]

Distribution[]

According to Joseph Jacobs's Europa's Fairy Book, the tale format is widespread[117][79] throughout Europe[118] and Asia (Middle East and India).[119] Portuguese writer, playwright and literary critic Teófilo Braga, in his Contos Tradicionaes do Povo Portuguez, confirms the wide area of presence of the tale, specially in Italy, France, Germany, Spain and in Russian and Slavic sources.[120]

The tale can also be found across Brazil, Syria, "White Russia, The Caucasus, Egypt, Arabia".[121]

Russian comparative mythologist Yuri Berezkin pointed out that the tale type can be found "from Ireland and Maghreb, to India and Mongolia", in Africa and Siberia.[122]

Possible point of origin[]

At first glance, scholarship admits some antiquity to the tale type, due to certain "primitive" elements, such as "the alleged birth of an animal or monster to a woman".[123]

Mythologist Thomas Keightley, in his 1834 book Tales and Popular Fictions, suggested the transmission of the tale from a genuine Persian source, based on his own comparison between Straparola's literary version and the one from The Arabian Nights ("The Sisters envious of their Cadette").[124][e] This idea seems to have been corroborated by Jiri Cejpek, who, according to Ulrich Marzolph, claimed that the tale of The Jealous Sisters was "definitely Iranian", but acknowledged that it must have not belonged to the original Persian compilation.[126]

The Brothers Grimm, commenting on the German version they collected, De drei Vugelkens, suggested that the tale developed independently in Köterberg, due to Germanic localisms present in the text.[127]

Another theory is that the Middle East is the possible point of origin or dispersal,[128] due to the great popularity of the tale in the Arab world.[129]

On the other hand, Joseph Jacobs, in his notes on Europa's Fairy Book, proposed a European provenance, based on the oldest extant version registered in literature (Ancilotto, King of Provino).[130]

Another position is sustained by scholar Ulrich Marzolph, who defends the existence of "an as yet unknown tradition" that originated Straparola's and Diyab's variants.[131]

has suggested that this tale has an even earlier point of origin, with a possible source in Hellenistic times.[132]

It has been suggested by Russian scholars that the first part of the tale (the promises of the three sisters and the substitution of babies for animals/objects) may find parallels in stories of the indigenous populations of the Americas.[133]

Scholar Linda Dégh put forth a theory of a common origin for tale types ATU 403 ("The Black and the White Bride"), ATU 408 ("The Three Oranges"), ATU 425 ("The Search for the Lost Husband"), ATU 706 ("The Maiden Without Hands") and ATU 707 ("The Three Golden Sons"), since "their variants cross each other constantly and because their blendings are more common than their keeping to their separate type outlines" and even influence each other.[134]

An Asian source?[]

Professor Jack Zipes, in turn, proposed that, although the tale has many ancient literary sources, it "may have originated in the Orient", but no definitive source has been indicated.[135]

W. A. Clouston claimed that the ultimate origin of the tale was a Buddhist tale of Nepal, written in Sanskrit, about King Brahmadatta and peasant Padmavatí (Padumavati) who gives birth to twins. However, the king's other wives cast the twins in the river.[136][137] Padmavati's birth is also a curious tale: on a hot summer day, seer Mandavya puts away a pot with urine and semen and a doe drinks it, thinking it to be water. The doe, which lives in the armitage, gives birth to a human baby. The girl is found by Mandavya and becomes a beautiful young maiden. One day, king Brahmadatta, from Kampilla, on a hunt, sees the beautiful maiden and decides to make her his wife.[138] This tale is contained in the Mahāvastu.[139]

Norwu-preng'va[]

French scholar Gédeon Huet supplied the summary of another Asian story: a Mongolian translation by European missionary Isaac Jacob Schmidt of a Tibetan work titled Norwou-prengva.[140][141] The Norwu-preng'wa was erroneously given as the title of the Mongolian source. However, the work is correctly named Erdeni-yin Tobci, compiled by Sagand Secen in 1662.[142][143]

In this tale, titled Die Verkörperung des Arja Palo (Avalokitas'wara oder Chongschim Bodhissatwa) als Königssöhn Erdeni Charalik, princess Ssamantabhadri, daughter of king Tegous Tsoktou, goes to bathe with her two female slaves in the river. The slaves, envious of her, suggest a test: the slaves will put their copper basins in the water, knowing it will float, and the princess should put her gold basin, unaware it will sink. It so happens and the princess, distraught at the loss of the basin, sends a slave to her father to explain the story. The slave arrives at the court of the king, who explains it will not reprimand his daughter. This slave returns and spins a lie that the king shall banish her to another kingdom with her two slaves. Resigning to her fate, she and the slaves wander to another kingdom, where they meet King Amugholangtu Yabouktchi (Jabuktschi). The monarch inquires about their skills: one slave answers she can weave clothes for one hundred men with a few pieces of fabric; the second, that she can prepare a meal worthy of one hundred men with just a handful of rice; the princess, at last, says she is a simple girl with no skills, but, due to her virtuous and pious devotion, the Three Jewels will bless her with a son "with the chest of gold, the kidneys of mother-of-pearl, the legs the color of the ougyou jewel". The "Great and Merciful Arya Palo" descends from "Mount Potaia" and enters the body of the princess. The child is born and the slaves bury him under the steps of the palace. The child gives hints of his survival and the slaves, now queens, try to hide the boy under many places of the palace, including the royal stables, which cause the horses not to approach it. The two slaves now bury the boy in the garden and a "magical plant of three colours" sprouts from the ground. The king wants to see it, but the plant has been eaten by sheep. A wonderful sheep is born some time later and, to the shepherd's surprise, it can talk. The baby sheep then transforms into a beggar youth, goes to the door of the palace and explains the whole story to the king. The youth summons a palace near the royal castle, invites the king, his mother and introduces himself as Erdeni Kharalik, their son. With his powers, he kills the envious slaves. Erdeni's story continues as a Buddhistic tale.[141]

Tripitaka[]

Folklorist Christine Goldberg, in the entry of the tale type in Enzyklopädie des Märchens, stated the tale of slander and vindication of the calumniated spouse appears in a story from the Tripitaka.[144]

French sinologist Édouard Chavannes translated the Tripitaka, wherein three similar stories of calumniated wives and multiple pregnancies are attested. The first one, given the title La fille de l'ascète et de la biche ("The daughter of the ascetic and the doe"), a deer licks the urine of an ascetic and becomes pregnant. It gives birth to a human child who is adopted by a brahman. She tends the fire at home. One day, the fire is put out because she played with the deer, and the brahmane sends her to fetch another flint for the fire. She comes to a house in the village, and, with every step she takes, a lotus flower sprouts. The owner of the house agrees to lend her a torch, after she circles the house three times to create a garden of lotus flowers. Her deeds reach the king's ears, who consults a diviner to see if marrying the maiden bodes well for his future. The diviner confirms it and the king marries the maiden. She becomes his queen and gives birth to one hundred eggs. The king's other wives of the harem take the eggs and throw them in the water. They are carried down by the river to another kingdom and are rescued by another sovereign. The eggs hatch and out come one hundred youths, described by the narrative as possessing great beauty, strength, and intelligence. They wage war on the neighbouring kingdoms, onw of which their biological father's. Their mother climbs up a tower and shoot her breastmilk, which falls "like darts or arrows" in the mouths of the 100 hundred warriors. They recognize their familial bond and cease the aggressions. The narrator says that the mother of the 100 sons is Chö-miao, mother of Çakyamuni. [145][146]

In a second tale from the Tripitaka, titled Les cinq cents fils d'Udayana ("The Five Hundred Sons of Udayana"), an ascetic named T'i-po-yen (Dvaipayana) urinates on a rock. A deer licks it and becomes pregnant with a human child. It gives birth to a daughter who grows up strong and beautiful, and with the ability to spring lotus flowers with every step. She tends the fire at home and, when it is put out, she goes to a neighbour to borrow some of their bonfire. The neighbour agrees to lend it to her, but first she must circle his house seven times to create a ring of lotus flowers. King Wou-t'i yan (Udayana) sees the lotus flowers and takes the girl as his second wife. SHe gives birth to 500 eggs, which are replaced for 500 bags of flour by the king's first wife. The first wife throws the eggs in a box in the Ganges, which are saved by another king, named Sa-tan-p'ou. The eggs hatch and 500 hundred boys are born and grow up as strong warriors. King Sa-tan-p'ou refuses to pay his tributes to king Wou-t'i-yen and attacks him with the 500 boys. Wou-t'i-yen asks for the help of the second wife: she puts her on a white elephant and she shoots 250 jets of milk from each breast. Each jet falls in each warrior's mouth. The war is ended, mother and sons recognize each other, and the 500 sons become the "Pratyeka Buddhas".[147][148]

In a third tale, Les mille fils d'Uddiyâna ("The Thousand Sons of Uddiyâna"), the daughter of the ascetic and the deer marries the king of Fan-yu (Brahmavali) and gives birth to one thousand lotus leaves. The king's first wife replaces them for a mass of equine meat and throws them in the Ganges. The leaves are saved by the king of Wou-k'i-yen (Uddiyâna) and from every leave comes out a boy. The thousand children grow up and become great warriors, soon doing battle with the realm of Fan-yu. Their mother climbs up a tower and shoots her breastmilk into their mouths.[149][150]

Earliest literary sources[]

The first attestation of the tale is possibly Ancilotto, King of Provino, an Italian literary fairy tale written by Giovanni Francesco Straparola in The Facetious Nights of Straparola (1550–1555).[151][152] A fellow Italian scholar, bishop (anagrammatised into nom de plume Marsillo Reppone), wrote down his own version of the story, in Posilecheata (1684), preserving the Neapolitan accent in the books' pages: La 'ngannatora 'ngannata, or L'ingannatora ingannata ("The deceiver deceived").[153][154][155]

Spanish scholars suggest that the tale can be found in Iberia's literary tradition of the late 15th and early 16th centuries: Lope de Vega's commedia La corona de Hungría y la injusta venganza contains similarities with the structure of the tale, suggesting that the Spanish playwright may have been inspired by the story,[156] since the tale is present in Spanish oral tradition. In the same vein, Menéndez Y Pelayo writes in his literary treatise Orígenes de la Novela that an early version exists in Contos e Histórias de Proveito & Exemplo, published in Lisbon in 1575,[157] but this version lacks the fantastical motifs.[158][159]

Two ancient French literary versions exist: Princesse Belle-Étoile et Prince Chéri, by Mme. D'Aulnoy (of Contes de Fées fame), in 1698,[160] and L'Oiseau de Vérité ("The Bird of Truth"), penned by French author Eustache Le Noble, in his collection La Gage touché (1700).[161][162]

Europe[]

Italy[]

Italy seems to concentrate a great number of variants, from Sicily to the Alps.[121] Henry Charles Coote proposed an Eastern origin for the tale, which later migrated to Italy and was integrated into the Italian oral tradition.[163]

The "Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi" ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage") promoted research and registration throughout the Italian territory between the years 1968–1969 and 1972. In 1975 the Institute published a catalog edited by Alberto Maria Cirese and Liliana Serafini including 55 variants of the ATU 707 type.[164]

Regional tales[]

Italian folklorist of Sicilian origin, Giuseppe Pitrè collected at least five variants in his book Fiabe Novelle e Racconti Popolari Siciliani, Vol. 1 (1875).[165] Pitrè also commented on the presence of the tale in Italian scholarly literature of his time. His work continued in the supplement publication of Curiosità popolari tradizionali, which recorded a variant from Lazio (Gli tre figli);[166] and a variant from Sardinia (Is tres sorris; English: "The three sisters").[167]

An Italian variant named El canto e 'l sono della Sara Sybilla ("The Sing-Song of Sybilla Sara"), replaces the magical items for an indescribable MacGuffin, obtained from a supernatural old woman. The strange object also reveals the whole plot at the end of the tale.[168] Vittorio Imbriani, who collected the previous version, also gathers three more in the same book La Novellaja Fiorentina: L'Uccellino, che parla; L'Uccel Bel-Verde and I figlioli della campagnola.[169] , a fellow Italian scholar, has recorded El canto e 'l sono della Sara Sybilla and I figlioli della campagnola, in his Sessanta novelle popolari montalesi: circondario di Pistoia[170] The story of "Sara Sybilla" has been translated to English as The Sound and Song of the Lovely Sibyl, with a source in Tuscany, but differing from the original in that it reinserts the bird as the truth-teller to the King.[171]

Vittorio Imbriani also compiles a Milanese version (La regina in del desert), which he acknowledges as a sister story to that of Sarnelli's and Straparola's.[172]

Fellow folklorist Laura Gonzenbach, from Switzerland, translated a Sicilian variant into the German language: Die verstossene Königin und ihre beiden ausgesetzten Kinder (The banished queen and her two children).[173]

Domenico Comparetti collected a variant named Le tre sorelle ("The Three Sisters"), from Monferrato[174] and L'Uccellino che parla ("The speaking bird"), a version from Pisa[175] – both in Novelline popolari italiane.

collected a version from Abruzzo, in Italy, named Lu fatte de le tré ssurèlle, with references to Gonzenbach, Pitrè, Comparetti and Imbriani.[176]

In a fable from Mantua (La fanciulla coraggiosa, or "The brave girl"), the story of the siblings's mother and aunts and the climax at the banquet are skipped altogether. The tale is restricted to a quest for the water-tree-bird to embellish their garden.[177]

Angelo de Gubernatis lists two variants from Santo Stefano di Calcinaia: I cagnolini and Il Re di Napoli,[178] and an unpublished, nameless version collected in Tuscany, near the source of the Tiber river.[179][180]

Carolina Coronedi-Berti collected a variant from Bologna called La fola del trèi surèl ("The tale of the three sisters"), with annotations to similar tales in other compilations of that time.[181] Ms. Coronedi-Berti mentioned two Pemontese versions, written down by Antonio Arietti: I tre fradej alla steila d'ör and Storia dël merlo bianc, dla funtana d'argent e dël erbolin che souna.[182] Coronedi-Berti also referenced two Venetian variants collected by Domenico Giuseppe Bernoni: El pesse can,[183] where the peasant woman promises twins born with special traits, and Sipro, Candia e Morea,[184] where the three siblings (one male, two female) are exposed by the evil maestra of the witch princess.

Christian Schneller collected a variant from Wälschtirol (Trentino), named Die drei Schönheiten der Welt (Italian: "La tre belleze del mondo"; English: "The three beauties of the world"),[185] and another variant in his notes to the tale.[186]

collected a version from Livorno, titled Le tre ragazze (English: "The three girls"), and compared it to other variants from Italy: L'albero dell'uccello que parla, L'acqua brillante e l'uccello Belverde, L'acqua que suona, l'acqua que balla e l'uccello Belverde que canta and L'Uccello Belverde from Spoleto; Le tre sorelle, from Polino; and L'albero que canta, l'acqua d'oro e l'uccello que parla, from Norcia.[187]

British lawyer Henry Charles Coote translated a version collected in Basilicata, titled The Three Sisters. The third sister only wishes to be the king's wife, she gives birth to "beautiful" children (the third a girl "beautiful as ray of sun"), the magical objects are "the yellow water, the singing bird and the tree that makes sounds like music", and the bird transforms into a fairy who reveals the truth to the king.[188] This tale was translated by German writer Paul Heyse with the name Die drei Schwestern.[189]

A singular tale, attributed to Italian provenance, but showing heavy Eastern inspiration (locations such as the Yellow River or the Ganges), shows the quest for "the dancing water, the singing stone and the talking bird".[190]

France[]

In French sources, there have been attested 35 versions of the tale (as of the late 20th century).[191] 19th century scholar Francis Hindes Groome noted that the tale could be found in Brittany and Lorraine.[121] A similar assessment, by researcher Gael Milin, asserted that the tale type was bien attesté ("well attested") in the Breton folklore of the 19th century.[192]

Regional tales[]

François-Marie Luzel collected from Brittany Les trois filles du boulanger, or L'eau qui danse, le pomme qui chante et l'oiseau de la verité[193] ("The Baker's Three Daughters, the Dancing Water, The Singing Apple, and the Bird of Truth")[194] - from Plouaret -,[195] and Les Deux Fréres et la Soeur ("The Two Brothers and their Sister"), a tale heavily influenced by Christian tradition.[196] He also provided a summary of a variant from Lorient: the king goes to war while his wife gives birth to two boys and a girl. The queen mother exchanges her son's letter and orders the children to be cast in the water and the wife to be mured. The children are saved by a miller and his wife, who raise the children and live comfortably well due to a coin purse that appears under the brothers' pillow every night. Years later, they go in search of their birth parents and come to a castle, where are located the "pomme qui chante, l'eau qui danse et l'oiseau qui parle". They must cross a graveyard before they reach the castle, where a fairy kill those who are impolite to her. The brothers fail, but the sister acts politely and receives from the fairy a cane to revive everyone at the graveyard. They find their father, the king, but arrive too late to save their mother.[197]

Jean-François Bladé recorded a variant from Gascony with the title La mer qui chante, la pomme qui danse et l'oisillon qui dit tout ("The Singing Sea, The Dancing Apple and The Little Bird that tells everything").[198][199] This tale preserves the motif of the wonder-children born with chains of gold "between the skin and muscle of their arms",[200] from Dolopathos and the cycle of The Knight of Swan.

Other French variants are: La branche qui chante, l'oiseau de vérité et l'eau qui rend verdeur de vie ("The singing branch, the bird of truth and the water of youth"), by Henri Pourrat; L'oiseau qui dit tout, a tale from Troyes collected by Louis Morin;[201] a tale from the Ariège region, titled L'Eau qui danse, la pomme qui chante et l'oiseau de toutes les vérités ("The dancing water, the singing apple and the bird of all truths");[202] a variant from Poitou, titled Les trois lingêres, by ;[203] a version from Limousin (La Belle-Étoile), by ;[204] and a version from Sospel, near the Franco-Italian border (L'oiseau qui parle), by James Bruyn Andrews.[205]

Emmanuel Cosquin collected a variant from Lorraine titled L'oiseau de vérité ("The Bird of Truth"),[206] which is the name used by French academia to refer to the tale.[207]

A tale from Haute-Bretagne, collected by Paul Sébillot (Belle-Étoile), is curious in that if differs from the usual plot: the children are still living with their mother, when they, on their own, are spurred on their quest for the marvelous items.[208] Sébillot continued to collect variants from across Bretagne: Les Trois Merveilles ("The Three Wonders"), from Dinan.[209]

A variant from Provence, in France, collected by (L'Arbre qui chante, l'Oiseau qui parle et l'Eau d'or, or "The tree that sings, the bird that speaks and the water of gold"), has the youngest daughter, the princess, marry an enchanted old man she meets in her journey and who gives her advice on how to obtain the items.[210]

An extended version, almost novella-length, has been collected from a Breton source and translated into French, by Gabriel Milin and Amable-Emmanuel Troude, called L'Oiseau de Vérité (Breton: Labous ar wirionez).[211] The tale is curious in that, being divided in three parts, the story takes its time to develop the characters of the king's son and the peasant wife, in the first third. In the second part, the wonder-children are male triplets, each with a symbol on his shoulder: a bow, a spearhead and a sword. The character who helps the youngest prince is an enchanted princess, who, according to a prophecy by her godmother, will marry the youngest son (the hero of the tale).

In another Breton variant, published in Le Fureteur breton (fr), the third seamstress sister wants to marry the prince, and, on her wedding day, reveals she will give birth to twins, a boy with a fleur-de-lis mark on the shoulder, and a girl.[192]

Iberian Peninsula[]

There are also variants in Romance languages: a Spanish version called Los siete infantes, where there are seven children with stars on their foreheads,[212] and a Portuguese one, As cunhadas do rei (The King's sisters-in-law).[213] Both replace the fantastical elements with Christian imagery: the devil and the Virgin Mary.[214]

A variant in verse format has been collected from the Madeira Archipelago.[215] Another version has been collected in the Azores Islands.[216]

Portugal[]

Brazilian folklorist Luís da Câmara Cascudo suggested that the tale type migrated to Portugal brought by the Arabs.[217]

Spain[]

American fairy tale and Hispanist Ralph Steele Boggs (de) published in 1930 a structural analysis of the tale type in Spanish sources.[218] According to him, a cursory glance at the material indicated that the tale type was "very popular in Spanish".[219]

Modern sources, from the 20th century and early 21st century, confirm the wide area of distribution of tale across Spain:[220] in Catalonia,[121] Asturias, Andalusia, Extremadura, New Castilla;[221] and in Province of Ciudad Real.[222] Scholar has published a catalogue of the variants of ATU 707 that can be found in Spanish sources (1997).[223]

Researcher James M. Taggart commented that the tale type was one of "the most popular stories about brothers and sisters" told by tellers in Cáceres, Spain (apart from types AT 327, 450 and 451). Interpreting this data under a sociological lens, he remarked that the heroine's role in rescuing her brother reflects the expected feminine task of "maintaining family unity".[224]

Regional tales[]

In compilations from the 19th century, collector D. Francisco de S. Maspons y Labros writes four Catalan variants: Los Fills del Rey ("The King's Children"), L'aygua de la vida ("The Water of Life"),[225] Lo castell de irás y no hi veurás and Lo taronjer;[226] collected a variant from Extremadura, named El papagayo blanco ("The white parrot");[227] Juan Menéndez Pidal a version from the Asturias (El pájaro que habla, el árbol que canta y el agua amarilla);[228] Antonio Machado y Alvarez wrote down a tale from Andalusia (El agua amarilla);[229] writer Fernán Caballero collected El pájaro de la verdad ("The Bird of Truth");[230] Wentworth Webster translated into English a variant in Basque language (The singing tree, the bird which tells the truth, and the water that makes young)[231]

Some versions have been collected in Mallorca, by Antoni Maria Alcover: S'aygo ballant i es canariet parlant ("The dancing water and the talking canary");[232] Sa flor de jerical i s'aucellet d'or;[233] La Reina Catalineta ("Queen Catalineta"); La bona reina i la mala cunyada ("The good queen and the evil sister-in-law"); S'aucellet de ses set llengos; S'abre de música, sa font d'or i s'aucell qui parla ("Tree of Music, the Fountains of Gold and the Bird that Talks").[234]

A variant in the Algherese dialect of the Catalan language, titled Lo pardal verd ("The Green Sparrow"), was collected in the 20th century.[235]

The tale El Papagayo Blanco was translated as The White Parrot by writer Elsie Spicer Eells in her book Tales of Enchantment from Spain: a sister and a brother live together, but the sister, spurred by an old lady, sends her brother to meet her whimsical demands (the fountain, the tree and the bird). At the end of the tale, after saving her brother, the sister regrets sending him on that dangerous quest.[236]

United Kingdom and Ireland[]

According to Daniel J. Crowley, British sources point to 92 variants of the tale type. However, he specified that most variants were found in the Irish Folklore Archives, plus some "scattered Scottish and English references".[237]

Scottish folklorist John Francis Campbell mentioned the existence of "a Gaelic version" of the French tale Princesse Belle-Étoile, itself a literary variant of type ATU 707. He also remarked that "[the] French story agree[d] with Gaelic stories", since they shared common elements: the wonder children, the three treasures, etc.[238]

Ireland[]

Scholarship points to the existence of many variants in Irish folklore. In fact, the tale type shows "wide distribution" in Ireland. However, according to researcher Maxim Fomin, this diffusion is perhaps attributed to a printed edition of The Arabian Nights.[239]

One version was published in journal Béaloideas with the title An Triúr Páiste Agus A Dtrí Réalta: a king wants to marry a girl who can jump the highest; the youngest of three sisters fulfills the task and becomes queen. When she gives birth to three royal children, their aunts replace them with animals (a young pig, a cat and a crow). The queen is cast into a river, but survives, and the king marries one of her sisters. The children are found and reared by a sow. When the foster mother is threatened to be killed on orders of the second queen, she gives the royal children three stars, a towel that grants unlimited food and a magical book that reveals the truth of their origin.[240]

Another variant has been recorded by Irish folklorist Sean O'Suilleabhain in Folktales of Ireland, under the name The Speckled Bull. In this variant, a prince marries the youngest of two sisters. Her elder sisters replaces the prince's children (two boys), lies that the princess gave birth to animals and casts the boys in a box into the sea, one year after the other. The second child is saved by a fisherman and grows strong. The queen's sister learns of the boy's survival and tries to convince his foster father's wife that the child is a changeling. She kills the boy and buries his body in the garden, from where a tree sprouts. Some time later, the prince's cattle grazed near the tree and a cow eats its fruit. The cow gives birth to a speckled calf that becomes a mighty bull. The queen's sister suspects the bull is the boy and feigns illness to have it killed. The bull escapes by flying to a distant kingdom in the east. The princess of this realm, under a geasa to always wear a veil outdoors lest she marries the first man she sets eyes on, sees the bull and notices it is a king's son. They marry, and the speckled bull, under a geas, chooses to be a bull by day and man by night. The bull regains human form and rescues his mother.[241]

In Types of the Irish Folktale (1963), by the same author, he listed a variant titled Uisce an Óir, Crann an Cheoil agus Éan na Scéalaíochta.[242]

Scotland[]

As a parallel to the Irish tale An Triúr Páiste Agus A Dtrí Réalta, published in Béaloideas, J. G McKay commented that the motif of the replacement of the newborns for animals occurs "in innumerable Scottish tales.".[243]

Wales[]

In a Welsh-Romani variant, Ī Tārnī Čikalī ("The Little Slut"), the protagonist is a Cinderella-like character who is humiliated by her sisters, but triumphs in the end. However, in the second part of the story, she gives birth to three children (a girl first, and two boys later) "girt with golden belts". They children are replaced for animals and taken to the forest. Their mother is accused of imaginary crimes and sentenced to be killed, but the old woman helper (who gave her the slippers) turns her into a sow, and tells her she may be killed and her liver taken by the hunters, by she will prevail in the end. The sow meets the children in the forest. The sow is killed, but, as the old woman prophecizes, her liver gained magical powers and her children use it to suit their needs. A neighbouring king wants the golden belts, but once they are taken from the boys, they become swans in the river. Their sister goes to the liver and wishes for their return to human form, as well as to get her mother back. The magical powers of the liver grant her wishes.[244][245]

Greece and Mediterranean Area[]

Greek scholar Marianthi Kaplanoglou states that the tale type ATU 707, "The Three Golden Children", is an "example" of "widely known stories (...) in the repertoires of Greek refugees from Asia Minor".[246] Professor Michael Meraklis commented that some Greek and Turkish variants have the quest for an exotic woman named "Dunja Giuzel", "Dünya Güzeli" or "Pentamorphé".[247]

In a tale from male storyteller Katinko, a Greek refugee in Asia Minor born in 1894, the king marries three sisters, the youngest promising to give birth to a boy named Sun and a girl named Moon. After they are cast in the water, they are saved and grow up near the palace. Soon enough, a magician spurs Moon, the sister, to send her brother, the Sun, on a quest for "the magic apples, the birds which sing all day and Dünya-Güzeli, the Fair One of the World". The character of Dünya-Güzeli serves as the Speaking Bird and reveals the whole truth.[248]

Greece[]

Fairy tale scholars point that at least 265 Greek versions have been collected and analysed by Angéloupoulou and Brouskou.[249][250] Professor Michael Meraklis, on the other hand, mentioned a higher count: 276 Greek variants.[247]

According to researcher Marianthi Kaplanoglou, a local Greek oikotype of Cinderella ("found in diverse geographical areas but mainly in southern Greece") continues as tale type ATU 707 (or as type ATU 403, "The Black and White Bride").[251] In the same vein, professor Michael Meraklis argued that the contamination of the "Cinderella" tale type with "The Three Golden Children" is due to the motif of the jealousy of the heroine's sisters.[247]

Scholar and writer Teófilo Braga points that a Greek literary version ("Τ' αθάνατο νερό"; English: "The immortal water") has been written by Greek expatriate (K. Ewlampios), in his book Ὁ Ἀμάραντος (German: Amarant, oder die Rosen des wiedergebornen Hellas; English: "Amaranth, or the roses of a reborn Greece") (1843).[252]

A variant was collected in the village of Zagori in Epirus, by J. G. Von Hahn in his Griechische und Albanische Märchen (Leipzig, 1864),[253] and analysed by Arthur Bernard Cook in his work Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion.[254] In Hahn's version, the third sister promises to give birth to twins, a boy and a girl "as beautiful as the morning star and the evening star".

Some versions have been analysed by Arthur Bernard Cook in his Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion (five variants),[255] and by W. A. Clouston in his Variants and analogues of the tales in Vol. III of Sir R. F. Burton's Supplemental Arabian Nights (1887) (two variants), as an appendix to Sir Richard Burton's translation of The One Thousand and One Nights.[256]

Two Greek variants alternate between twin children (boy and girl)[257][258] and triplets (two boys and one girl).[259][260][261][262] Nonetheless, the tale's formula is followed to the letter: the wish for the wonder-children, the jealous relatives, the substitution for animals, exposing the children, the quest for the magical items and liberation of the mother.

In keeping with the variations in the tale type, a tale from Athens shows an abridged form of the story: it keeps the promises of the three sisters, the birth of the children with special traits (golden hair, golden ankle and a star on forehead), and the grandmother's pettiness, but it skips the quest for the items altogether and jumps directly from a casual encounter with the king during a hunt to the unveiling of truth during the king's banquet.[263][264] A similar tale, The Three Heavenly Children, attests the consecutive births of three brothers (sun, moon and firmament) and the king overhearing his own sons narrating each other the story in their foster father's hut.[265][266]

Albania[]

Albanian variants can be found in the works of many folklorists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Auguste Dozon collected another version in his Contes Albanais with the title Les Soeurs Jaleuses (or "The Envious Sisters").[267][268] In this version, after their father, the previous king, dies, three sisters talk at night - an event eavesdropped by the newly-crowned king. The third sister promises to give birth to twins, a boy and a girl with "with a star on the brow and a moon on the breast". Dozon noted that it was a variant of the story published by von Hahn.[269]

Dozon's tale was also translated into German by linguist August Leskien in his book of Balkan folktales, with the title Die neidischen Schwestern.[270] In his commentaries, Leskien noted that the tale was classified as type 707, according to the then recent Antti Aarne's index (published in 1910).[271]

Robert Elsie, German scholar of Albanian studies, translated the same version in his book Albanian Folktales and Legends. In his translation, titled The youth and the maiden with stars on their foreheads and crescents on their breasts, the third sister, daughter of the recently deceased previous king, promises to give birth to twins, a boy and a girl "with stars on their foreheads and crescents on their breast".[272] The original name of the tale, in Albanian, as provided by Elsie, was "Djali dhe vajza me yll në ball dhe hënëz në kraharuar".[273]

Slavicist André Mazon (fr), in his study on Balkan folklore, published an Albanian language variant he titled Les Trois Soeurs. In this variant, the third sister promises to give birth to a boy with a moon on his breast and a girl with a star on the front. Despite lacking the quest for the items, Mazon recognized its correspondence to other tales, such as Russian "Tsar Saltan" and MMe. d'Aulnoy's "Belle-Étoile".[274]

Folklorist Anton Berisha published another Albanian language tale, titled "Djali dhe vajza me yll në ballë".[275]

Malta[]

A Maltese variant has been collected by Hans Stumme, under the name Sonne und Mond, in Maltesische Märchen (1904).[276] This tale begins with the ATU 707 (twins born with astronomical motifs/aspects), but the story continues under the ATU 706 tale-type (The Maiden without hands): mother has her hands chopped off and abandoned with her children in the forest.

A second Maltese variant was collected by researcher Bertha Ilg-Kössler (es), titled Sonne und Mond, das tanzende Wasser und der singende Vogel. In this version, the third sister gives birth to a girl named Sun, and a boy named Moon.[277]

Cyprus[]

At least one variant from Cyprus has been published, from the "Folklore Archive of the Cyprus Research Centre".[278]

Western and Central Europe[]

In a variant collected in Austria, by Ignaz and Joseph Zingerle (Der Vogel Phönix, das Wasser des Lebens und die Wunderblume, or "The Phoenix Bird, the Water of Life and the Most beautiful Flower"),[279] the tale acquires complex features, mixing with motifs of ATU "the Fox as helper" and "The Grateful Dead": The twins take refuge in their (unbeknownst to them) father's house, it's their aunt herself who asks for the items, and the fox who helps the hero is his mother.[280] The fox animal is present in stories of the Puss in Boots type, or in the quest for The Golden Bird/Firebird (ATU 550 – Bird, Horse and Princess) or The Water of Life (ATU 551 – The Water of Life), where the fox replaces a wolf who helps the hero/prince.[281]

A variant from Buchelsdorf, when it was still part of Austrian Silesia (Der klingende Baum), has the twins raised as the gardener's sons and the quest for the water-tree-bird happens to improve the king's garden.[282]

In a Lovari Romani variant, the king meets the third sister during a dance at the village, who promised to give birth to a golden boy. They marry. Whenever a child is born to her (two golden boys and a golden girl, in three consecutive births), they are replaced for an animal and cast into the water. The king banishes his wife and orders her to be walled up, her eyes to be put on her forehead and to be spat on by passersby. An elderly fisherman and his wife rescue the children and name them Ējfēlke (Midnight), Hajnalka (Dawn) - for the time of day when the boys were saved - and Julishka for the girl. They discover they are adopted and their foster parents suggest they climb a "cut-glass mountain" for a bird that knows many things, and may reveal the origin of the parentage. At the end of their quest, young Julishka fetches the bird, of a "rusty old" appearance, and brings it home. With the bird's feathers, she and her brothers restore their mother to perfect health and disenchant the bird to human form. Julishka marries the now human bird.[283]

Germany[]

Portuguese folklorist Teófilo Braga, in his annotations, commented that the tale can be found in many Germanic sources,[284] mostly in the works of contemporary folklorists and tale collectors: The Three Little Birds (De drei Vügelkens), by the Brothers Grimm in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (number 96);[285][286] Springendes Wasser, sprechender Vogel, singender Baum ("Leaping Water, Speaking Bird and Singing Tree"), written down by Heinrich Pröhle in Kinder- und Völksmärchen,[287][288] Die Drei Königskinder, by Johann Wilhelm Wolf (1845); Der Prinz mit den 7 Sternen ("The Prince with 7 stars"), collected in Waldeck by Louis Curtze,[289] Drei Königskinder ("Three King's Children"), a variant from Hanover collected by Wilhelm Busch;[290] and Der wahrredende Vogel ("The truth-speaking bird"), an even earlier written source, by Justus Heinrich Saal, in 1767.[135] A peculiar tale from Germany, Die grüne Junfer ("The Green Virgin"), by , mixes the ATU 710 tale type ("Mary's Child"), with the motif of the wonder children: three sons, one born with golden hair, other with a golden star on his chest and the third born with a golden stag on his chest.[291]

A variant where it is the middle child the hero who obtains the magical objects is The Talking Bird, the Singing Tree, and the Sparkling Stream (Der redende Vogel, der singende Baum und die goldgelbe Quelle), published in the newly discovered collection of Bavarian folk and fairy tales of Franz Xaver von Schönwerth.[292] In a second variant of the same collection (The Mark of the Dog, Pig and Cat), each children is born with a mark in the shape of the animal that was put in their place, at the moment of their birth.[293]

In a Sorbian/Wendish (Lausitz) variant, Der Sternprinz ("The Star Prince"), three discharged soldier brothers gather at a tavern to talk about their dreams. The first two dreamt of extraordinary objects: a large magical chain and a inexhaustible purse. The third soldier says he dreamt that if he marries the princess, they will have a son with a golden star on the forehead ("słoćanu gwězdu na cole"). The three men go to the king and the third marries the princess, who gives birth to the promised boy. However, the child is replaced by a dog and thrown in the water, but he is saved by a fisherman. Years later, on a hunt, the Star Prince tries to shoot a white hind, but it says it is the enchanted Queen of Rosenthal. She alerts that his father and uncles are in the dungeon and his mother is to marry another person. She also warns that he must promise not reveal her name. He stops the wedding and releases his uncles. They celebrate their family reunion, during which the Star Prince reveals the Queen's name. She departs and he must go on a quest after her (tale type ATU 400, "The Quest for the Lost Wife").[294][295]

Belgium[]

Professor Maurits de Meyere listed three variants under the banner "L'oiseau qui parle, l'arbre qui chante et l'eau merveilleuse", attested in Flanders fairy tale collections, in Belgium, all with contamination from other tale types (two with ATU 303, "The Twins or Blood Brothers", and one with tale type ATU 304, "The Dangerous Night-Watch").[296]

A variant titled La fille du marchand was collected by Emile Dantinne from the Huy region ("Vallée du Hoyoux"), in Wallonia.[297]

Switzerland[]

In a version collected from Graubünden with the title Igl utschi, che di la verdat or Vom Vöglein, das die Wahrheit erzählt ("The little bird that told the truth"), the tale begins in media res, with the box with the children being found by the miller and his wife. When the siblings grow up, they seek the bird of truth to learn their origins, and discover their uncle had tried to get rid of them.[298][299][300]

Another variant from Oberwallis (canton of Valais) (Die Sternkinder) has been collected by Johannes Jegerlehner, in his Walliser sagen.[301]

In a variant from Surselva, Ils treis lufts or Die drei Köhler ("The Three Charcoal-Burners"), three men meet in a pub to talk about their dreams. The first dreamt that he found seven gold coins under his pillow, and it came true. The second, that he found a golden chain, which also came true. The third, that he had a son with a golden star on the forehead. The king learns of their dreams and is gifted the golden chain. He marries his daughter to the third charcoal burner and she gives birth to the boy with a golden star. However, the queen replaces her grandson with a puppy and throws the child in the river.[302][303]

Hungary[]

Hungarian scholarship classify the ATU 707 tale under the banner of "The Golden-Haired Twins" (Hungarian: Az aranyhajú ikrek).[304] In the 19th century, Elisabet Róna-Sklárek also published comparative commentaries on Hungarian folktales in regards to similar versions in international compilations of the time.[305] Professor Ágnes Kovács commented that the tale type is frequent and widespread in Hungarian-language areas.[306] In the same vein, professor Linda Dégh stated that the national Hungarian Catalogue of Folktales (MNK) listed 28 variants of the tale type and 7 deviations.[307]

Fieldwork conducted in 1999 by researcher Zoltán Vasvári amongst the Palóc population found 3 variants of the tale type.[308]

Regional tales[]

According to scholarship, the oldest variant of the tale type in Hungary was registered in 1822.[309] This tale was published by Gyorgy von Gaal in his book Mährchen der Magyaren with the title Die Drillinge mit den Goldhaar ("The Triplets with Golden Hair"): the baker's three daughters, Gretchen, Martchen and Suschen each profess their innermost desire: the youngest wants to marry the king, for she will bear him two princes and one princess, all with golden hair and a golden star shining on the forehead.[310]

A variant translated by the Jeremiah Curtin (Hungarian: A sündisznó;[311] English: "The Hedgehog, the Merchant, the King and the Poor Man") begins with a merchant promising a hedgehog one of his daughters, after the animal helped him escape a dense forest. Only the eldest agrees to be the hedgehog's wife, which prompts him to reveal his true form as a golden-haired, golden-mouthed and golden-toothed prince. They marry and she gives birth to twins, Yanoshka and Marishka. Her middle sister, seething with envy, dumps the royal babies in the forest, but they are reared by a Forest Maiden. When they reach adulthood, their aunt sets them on a quest for "the world-sounding tree", "the world-sweetly speaking bird" and "the silver lake [with] the golden fish".[312] Elek Benedek collected the second part of the story as an independent tale named Az Aranytollú Madár ("The Golden-Feathered Bird"), where the children are reared by a white deer, a golden-feathered bird guides the twins to their house, and they seek "the world-sounding tree", "the world-sweetly speaking bird" and "the silver lake [with] the golden fish".[313]

In a third variant, A Szárdiniai király fia ("The Son of the King of Sardinia"), the youngest sister promises golden-haired twins: a boy with the sun on his forehead, and a girl with a star on the front.[314]

In the tale A mostoha királyfiakat gyilkoltat, the step-parent asks for the organs of the twin children to eat. They are killed, their bodies are buried in the garden and from their grave two apple trees sprout.[315]

In another Hungarian tale, A tizenkét aranyhajú gyermek ("The Twelve Golden-Haired Children"), the youngest of three sisters promises the king to give birth to twelve golden-haired boys. This variant is unique in that another woman also gives birth to twelve golden-haired children, all girls, who later marry the twelve princes.[316]

In the tale A tengeri kisasszony ("The Maiden of the Sea"), the youngest sister promises to give birth to an only child with golden hair, a star on his forehead and a moon on his chest. The promised child is born, but cast into the water by the cook. The miller finds the boy and raises him. Years later, the king, on a walk, takes notice of the boy and adopts him, which was consented by the miller. When the prince comes to court, the cook convinces the boy to search for "the bird that drinks from the golden and silver water, and whose singing can be heard from miles", the mirror that can see the whole world and the Maiden of the Sea.[317]

Another version, Az aranyhajú gyermekek ("The Golden-Haired Children"), skips the introduction about the three sisters: the queen gives birth to a boy with a golden star on the forehead and a girl with a small flower on her arm. They end up adopted by a neighbouring king and an old woman threatens the girl with a cruel punishment if the twins do not retrieve the bird from a cursed castle.[318]

In the tale A boldogtalan királyné ("The Unhappy Queen"), the youngest daughter of a carpenter becomes a queen and bears three golden-haired children, each with a star on their foreheads. They are adopted by a fisherman; the boys become fine hunters and venture into the woods to find a willow tree, a talking bird on a branch and to collect water from a well that lies near the tree.[319]