The Boys with the Golden Stars

| The Boys with the Golden Stars | |

|---|---|

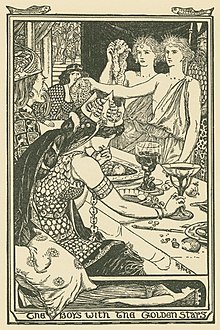

The boys with the golden stars, by Ford, H. J., in Andrew Lang's The Violet Fairy Book (1901). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Boys with the Golden Stars |

| Also known as | Doi feți cu stea în frunte The Twins with the Golden Star |

| Data | |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 707 (The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird; The Bird of Truth, or The Three Golden Children, or The Three Golden Sons) |

| Region | Romania, Eastern Europe |

| Related | The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird; Ancilotto, King of Provino; Princess Belle-Étoile and Prince Chéri; The Tale of Tsar Saltan; A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers |

The Boys with the Golden Stars (Romanian: Doi feți cu stea în frunte) is a Romanian fairy tale collected in Rumänische Märchen.[1] Andrew Lang included it in The Violet Fairy Book.[2] An alternate title to the tale is The Twins with the Golden Star.[3]

Origins[]

The Romanian tale Doi feți cu stea în frunte was first published in the Romanian magazine Convorbiri Literare, in October, 1874, and signed by Romanian author Ioan Slavici.[4]

Synopsis[]

A herdsman had three daughters, Ana, Stana and Laptița. The youngest was the most beautiful. One day, the emperor was passing with attendants. The oldest daughter said that if he married her, she would bake him a loaf of bread that would make him young and brave forever; the second one said, if one married her, she would make him a shirt that would protect him in any fight, even with a dragon, and against heat and water; the youngest one said that she would bear him twin sons with stars on their foreheads. The emperor married the youngest, and two of his friends married the other two.[a]

The emperor's stepmother had wanted him to marry her daughter and so hated his new wife. She got her brother to declare war on him, to get him away from her, and when the empress gave birth in his absence, killed and buried the twins in the corner of the garden and put puppies in their place. The emperor punished his wife to show what happened to those who deceived the emperor.

Two aspens grew from the grave, putting on years' growth in hours. The stepmother wanted to chop them down, but the emperor forbade it. Finally, she convinced him, on the condition that she had beds made from the wood, one for him and one for her. In the night, the beds began to talk to each other. The stepmother had two new beds made, and burned the originals. While they were burning, the two brightest sparks flew off and fell into the river. They became two golden fish. When fishermen caught them, they wanted to take them alive to the emperor. The fish told them to let them swim in dew instead, and then dry them out in the sun. When they did this, the fish turned back into babies, maturing in days.

Wearing lambskin caps that covered their hair and stars, they went to their father's castle and forced their way in. Despite their refusal to take off their caps, the emperor listened to their story, only then removing their caps. The emperor executed his stepmother and took back his wife.

Analysis[]

The birth of the wonder-children[]

Most versions of The Boys With Golden Stars[6] begin with the birth of male twins, but very rarely there are fraternal twins, a boy and a girl. When they transform into human babies again, the siblings grow up at an impossibly fast rate and hide their supernatural trait under a hood or a cap. Soon after, they show up in their father's court or house to reveal the truth through a riddle or through a ballad.[7]

The motif of a woman's babies, born with wonderful attributes after she claimed she could bear such children, but stolen from her, is a common fairy tale motif; see "The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird", "The Tale of Tsar Saltan", "The Three Little Birds", "The Wicked Sisters", "Ancilotto, King of Provino", and "Princess Belle-Etoile". Some of these variants feature an evil stepmother.

The reincarnation motif[]

The transformation chase where the stepmother is unable to prevent the children's reappearance is unusual, although it appears in "A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers" and in "The Count's Evil Mother" (O grofu i njegovoj zloj materi), a Croatian tale from the Karlovac area,[8] in the Kajkavian dialect.[9] "The Pretty Little Calf" also has the child reappear, transformed after being murdered, but only has the transformation to an animal form and back to human.

Daiva Vaitkevičienė suggested that the transformation sequence in the tale format (from human babies, to trees, to lambs/goats and finally to humans again) may be underlying a theme of reincarnation, metempsychosis or related to a life-death-rebirth cycle.[10] This motif is shared by other tale types, and does not belong exclusively to the ATU 707.

French scholar Gédeon Huet noted the "striking" (frappantes) similarities between these versions of ATU 707 and the Ancient Egyptian story of The Tale of Two Brothers - "far too great to be coincidental", as he put it.[11]

India-born author Maive Stokes noted the resurrective motif of the murdered children, and found parallels among European tales published during that time.[12] Austrian consul Johann Georg von Hahn also remarked on a similar transformation sequence present in a Greek tale from Asia Minor, Die Zederzitrone, a variant of The Love for Three Oranges (ATU 408).[13]

Asian parallels[]

A similar occurrence of the tree reincarnation is attested in the Bengali folktale The Seven Brothers who were turned into Champa Trees[14] (Sat Bhai Chompa, first published in 1907)[15] and in the tale The Real Mother, collected in Simla.[16]

In a Thai tale, Champa Si Ton or The Four Princes (Thai: สี่ยอดกุมาร), king Phaya Chulanee, ruler of the City of Panja, is already married to a woman named Queen Akkee. He travels abroad and reaches the deserted ruins of a kingdom (City of Chakkheen). He saves a princess named Pathumma from inside a drum she was hiding in when some terrifying creatures attacked her kingdom, leaving her as the sole survivor. They return to Panja and marry. Queen Pathumma is pregnant with four sons, to the envy of the first wife. She replaces the sons for dogs to humiliate the second queen, and throws the babies in the river.[17] A version of the tale is also preserved in palm-leaf manuscript form. The tale continues as the four princes are rescued from the water and buried in the garden, only to become champa trees and later regaining their human shapes.[18]

In a Laotian version of Champa Si Ton, or The Four Champa Trees, King Maha Suvi is married to two queens, Mahesi and Mahesi Noi. Queen Mahesi gives birth to the four princes, who are taken to the water in a basket. When they are young, they are poisoned by the second queen and buried in the village, four champa trees sprouting on their graves. The second queen learns of their survival and orders the trees to be felled down and thrown in the river. A monk sees their branches with flowers and takes them off the river.[19]

A similar series of transformations is found in "Beauty and Pock Face" and "The Story of Tam and Cam".

In a Burmese tale titled The Big Tortoise, at the end of the tale, after she was replaced by her ugly stepsister, the heroine goes through two physical transformations: the heroine, Mistress Youngest, visits her stepfamily, who drops a cauldron of boiling water over her and she becomes a white paddy-bird. Later, the false bride kills her bird form and asks the cook to roast it. The cook buries the bird's remains behind the kitchen, where a quince tree sprouts. An old couple passes by the quince tree and a large fruit falls on their lap that they take home and put in an earthen jar. The fruit contains the true princess and, when the old couple leaves their cottage, the princess goes out of the earthen jar to tidy up the place.[20]

In a Chinese tale from Fujian, Da Jie (also a Cinderella variant), after Da Jie marries a rich scholar, her stepfamily devises a plan to replace her with Da Jie's smallpox-riddled stepsister, Xia Mei. Xia Mei shoves Da Jie into a well, but she turns into a sparrow, which communicates with her husband to alert him of the substitution. Xia Mei kills the sparrow and buries it in the garden. In that spot a bamboo tree grows, which soothes her husband and annoys the false spouse. Xia Mei decides to have the bamboo tree made into a bed. If the scholar sleeps on it, he feels refreshed; if the stepsister sleeps on it, she feels awful, so she notices it is Da Jie's doing. She orders the bed to be burnt down, but an old woman discovers its charred remains and brings them home. When she goes out and returns at night, she notices someone has prepared her dinner. On the third night, she senses the presence of Da Jie and helps her regain human form and later reunite her with the husband.[21]

Other regions[]

A similar transformation sequence occurs in French-Missourian folktale L'Prince Serpent Vert pis La Valeur ("The Prince Green Snake and La Valeur"), collected by Franco-Ontarian scholar Joseph Médard Carrière. After hero La Valeur disenchants Prince Green Snake, he receives a magical shirt and sabre. After being betrayed by his wife, the princess, La Valeur is resurrected into horse form by Prince Green Snake and returns to his wife's kingdom. The wife orders the horse to be killed, but before his death, La Valeur instructs a maid to save his first three droplets of blood. She does so and three laurel trees sprout. The traitorous princess recognizes the trees and orders them to be felled, but the maid rescues three wood chips, which become three ducks. Later, the three ducks fly to the magic shirt, disappear with it and La Valeur regains his human form.[22][b]

A similar cycle of transformations is attested in a Sicilian tale collected by folklorist Giuseppe Pitré from Montevago. In this tale (another variant of the tale type ATU 707), La cammisa di lu gran jucaturi e l'auceddu parlanti ("The Shirt of the Great Player and the Talking Bird"), the prince marries a poor maiden against his mother's wishes. She gives birth to 12 boys and a girl, which the queen buries in the garden. However, 12 orange trees and a lemon tree sprout in their place. A goatherder passes by the garden and one of his goats eats some of the leaves. It gives birth to the 13 siblings, who grow up and later seek three treasures.[24][25][26]

Greece[]

According to the Greek folktale catalogue of Angelopoulou and Brouskou, some Greek variants of type 707 contain the motif of the wonder-children and the rebirth as plants, animals and humans again. In one variant from Roccaforte del Greco, in Calabria, the third sister promises to give birth to 100 sons with a golden apple in the hand and a daughter with a golden star. They are buried, turn into 101 oranges trees, which are burned down. In their ashes, 100 grains of pepper and an aubergine that are eaten by a goat.[27]

In a tale from Arminou-Néa Pafos, La tisseuse, the mother promises to give birth to 101 children. They are buried and on their graves sprout 100 cypresses and one platanus tree. Their flowers are eaten by a goat and they return to human form.[28]

In a variant from Asia Minor, the tale begins with type ATU 510A, "Cinderella". The story continues as the princess gives birth to three sons of gold. They are buried and become trees. The villain orders the trees to be burnt down, but some sparks are eaten by a goat, which gives birth to the three sons anew. The Sun and its mother pass by the boys to provide them with clothes and gifts.[29]

In the tale Ό Ήλιος, ό Αύγερινός καί ή Πούλια (The Sun, the Morning-Star and the Pleiad), the older sister tells her sisters she dreamt she married the king and gave birth to "three beautiful children": Sun, Morning Star and Pleiad. The king overhears their conversation and marries the older sister. When they are born, "the room shone from their beauty". The midwife replaces them for puppies and buries them in the basement of the castle. The king calls for his children, and they answer him. He decides to erect a new palace, but the midwife takes the children's bones and buries them in the yard. Three cypress trees sprout. The midwife orders the trees to be felled down. Three flowers sprout and the queen sends her pet goat to eat them. The goat gets pregnant and the queen wants it killed. After her order is carried out, a slave girl washes its entrails in the river and the children reappear in human form.[30]

Distribution[]

The format of the story The Boys With The Golden Stars seems to concentrate around Eastern Europe: in Romenia;[31][32] a version in Belarus;[33] in Serbia;[34][35] in the Bukovina region;[36] in Croatia;[37][38] Bosnia,[39] Moldavia,[40] Bulgaria,[41] Poland, Ukraine, Czech Republic, Slovakia,[42][43][44] and among the Transylvanian Saxons.[45]

Hungarian scholar Ágnes Kovács stated that this was the "Eastern European subtype" of the tale Cei doi fraţi cu păr de aur ("The Twin Brothers With Golden Hair"), found "all across the Romanian language territories", as well in Hungarian speaking regions.[46]

Writer and folklorist Cristea Sandu Timoc considered that these tales were typically Romanian, and belonged to tale type AaTh 707C*. He also reported that "more than 70 variants" of this subtype were "known" (as of 1988).[47]

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva names this format "Reincarnation of the Luminous Twins" and considers this group of variants as "an ancient Slavic plot", since these tales have been collected from Slavic-speaking areas.[48] Another argument she raises is that the tree transformation in most variants is the sycamore, a tree with mythical properties in East Slavic folklore.[49] She also argues that this format is the "archaic version" of the tale type, since it shows the motif of the tree and animal transformation, and recalls ancient ideas of twin beings in folklore.[50]

On the other hand, according to researcher Maxim Fomin, Irish folklorist Seán Ó Súilleabháin identified this as a second ecotype (oikotype) of type ATU 707 in Ireland, which corresponds to the birth of the miraculous twins, their death by burial, and the cycle of transformations from plant to animal to humans again.[51]

Similarly, Lithuanian scholarship (namely, Bronislava Kerbelytė (lt) and Daiva Vaitkevičienė) lists at least 23 variants of this format in Lithuania. In these variants, the youngest sister promises to give birth to twins with the sun on the forehead, the moon on the neck and stars on the temples. A boy and a girl are born, but they are buried by a witch, and on their graves an apple tree and a pear tree sprout. They mostly follow the cycle of transformations (from human babies, to trees, to animals and finally to humans again), but some differ in that after they become lambs, they are killed and their ashes are eaten by a duck that hatches two eggs.[52] Kerbelyte locates most of the Lithuanian variants of this format in the Dzūkija region.[53]

According to the Latvian Folktale Catalogue, tale type 707, "The Three Golden Children", is known in Latvia as Brīnuma bērni ("Wonderful Children"), comprising 4 different redactions. Its third redaction follows The Boys with the Golden Stars: the twins are buried by their stepmother in the garden and go through a cycle of transformations (from babies, to trees, to burnt trees, to lambs, to humans again).[54]

Professor Reginetta Haboucha remarked that the reincarnation cycle of these variants (human - tree - sheep - human) constitutes a new type she identified as **707B, "Truth Comes to Light" - a combination between type 707 and "essential elements" from type AT 780A, "The Cannibalistic Brothers".[55]

Variants[]

Romania[]

A version of the tale, collected in the Wallachia region, from a Mihaila Poppowitsch, has an evil maid who murders the children, but at the end of the tale their father exiles the murderess instead of executing her.[56] The source of this variant was later identified as the Banat region.[57]

Another Romanian variant, Sirte-Margarita, can be found in Doĭne: Or, the National Songs and Legends of Roumania, by Eustace Clare Grenville Murray, and published in 1854.[58]

In another Romanian variant, A két aranyhajú gyermek ("The Two Children With Golden Hair"), the youngest sister promises the king to give birth to a boy and a girl of unparalleled beauty. Her sisters, seething with envy, conspire with the king's gypsy servant, take the children and bury them in the garden. After the twins are reborn as trees, they twist their branches to make shade for the king when he passes, and to hit their aunts when they pass. After they go through the rebirth cycle, the Sun, stunned at their beauty, clothes them and gives the boy a flute.[59]

In a variant from "Siebenburgen" (Transylvania), Die Schnitterin als Kaiserin ("The Harvester as Queen"), the maiden is made queen on the promise of bearing golden-haired twins. A "gypsy" who worked at the king's court, jealous of the newly-crowned queen, exchanges her children for two puppies and buries the babies in the garden. From their burial place, two Tännenbaum (fir trees) sprout.[60]

Writer and folklorist Cristea Sandu Timoc collected two other Romanian variants, published in 1988.[61] In one, Doi feţi logofeţi, collected from Ţăranu Dumitru, the third sister promises to give birth to twins as beautiful as gold and silver.[62] In the second, Trei fete mari in cînepă, collected from Sandru Gherghina, the third sister promises twins of gold and silver.[63] In both tales, the twins, a boy and a girl, go through the cycle of transformations (trees, animals, humans again).

Belarus[]

In a Belarussian tale, "Блізняткі" (The Twins), an evil witch kills two boys - the sons of the prince. On their grave two sycamores grow. The witch realizes it is the boys and orders the gardener to fell them down. A sheep licks the ashes and soon enough gives birth to two sheep - the very same princes. Later, they regain their human form and tell the king the whole story.[64]

Hungary[]

Hungarian scholarship classifies the ATU 707 tale under the banner of "The Golden-Haired Twins" (Hungarian: Az aranyhajú ikrek).[65]

In the tale A mostoha királyfiakat gyilkoltat, the step-parent asks for the organs of the twin children to eat. They are killed, their bodies are buried in the garden and from their grave two apple trees sprout.[66]

In the tale A mosolygó alma ("The Smiling Apple"), a king sends his page to pluck some fragant scented apples in a distant garden. When the page arrives at the garden, a dishevelled old man appears and takes him into his house, where the old man's three young daughters live. The daughters comment among themselves their marriage wishes: the third wishes to marry the king and give him two golden-haired children, one with a "comet star" on the forehead and another with a sun. The rest of the story follows The Boys with the Golden Star format.[67]

Other Magyar variant is Die zwei goldhaarigen Kinder (Hungarian: "A két aranyhajú gyermek";[68] English: "The Two Children with Golden Hair").[69] The tale begins akin to tale type ATU 450, "Brother and Sister", wherein the boy drinks from a puddle and becomes a deer, and his sister is found by the king during a hunt. The sister, in this variant, begs the king to take her, for she will bear him twin sons with golden hair. After the twin boys are born, they are buried in the ground and go through a cycle of transformations, from golden-leaved trees, to lambs to humans again. When they assume human form, the Moon, the Sun and the Wind give them clothes and shoes.

Adaptations[]

A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Magyar népmesék ("Hungarian Folk Tales") (hu), with the title A két aranyhajú fiú ("The Two Sons With Golden Hair").

Footnotes[]

References[]

- ^ Kremnitz, Mite. Rumänische Märchen. Übersetzt von -, Leipzig: Wilhelm Friedrich, 1882. pp. 29-42.

- ^ Lang, Andrew. The Violet Fairy Book. London; New York: Longmans, Green. 1906. pp. 299-310.

- ^ Kremnitz, Mite; Mary J Safford. Roumanian Fairy Tales. New York: H. Holt and company. 1885. pp. 30-41.

- ^ Slavici, Ioan. "Doi feți cu stea în frunte". In: Convorbiri Literare 08, nr. 07, 1 octombrie, 1874. Redactor: Jacob Negruzzi. Iași: Tipografia Națională, 1874. pp. 287-293.

- ^ Draucean, Adela Ileana (2008). "The Names of Romanian Fairy-Tale Characters in the Works of the Junimist Classics". In: Studii și cercetări de onomastică și lexicologie, II (1-2), p. 24. ISSN 2247-7330

- ^ A Companion to the Fairy Tale. Edited by Hilda Ellis Davidson and Anna Chaudhri. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. 2003. p. 43. ISBN 0-85991-784-3

- ^ "The Golden Twins". Ispirescu, Petre. The foundling prince, & other tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1917. pp. 65-84. [1]

- ^ (1997). Hrvatske bajke. Glagol, Zagreb.. The tale was first published in written form by Rudolf Strohal.

- ^ "Vom Grafen und seiner bösen Mütter". In: Berneker, Erich Karl. Slavische Chrestomathie mit Glossaren. Strassburg K.J. Trübner. 1902. pp. 226-229.

- ^ Vaitkevičienė, Daiva (2013). "Paukštė, kylanti iš pelenų: pomirtinis persikūnijimas pasakose" [The Bird Rising from the Ashes: Posthumous Transformations in Folktales]. Tautosakos darbai (in Lithuanian) (XLVI): 71–106. ISSN 1392-2831. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020.

- ^ Huet, Gédeon. "Le Conte des soeurs jalouses". In: Revue d'ethnographie et de sociologie. Deuxiême Volume. Paris: E. Leroux, 1910. Gr. in-8°, pp. 189-191.

- ^ Stokes, Maive. Indian fairy tales, collected and tr. by M. Stokes; with notes by Mary Stokes. London: Ellis and White. 1880. pp. 250-251.

- ^ Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1-2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. pp. 404.

- ^ Bradley-Birt, Francis Bradley; and Abanindranath Tagore. Bengal Fairy Tales. London: John Lane, 1920. pp. 150–152.

- ^ Roy, Arnab Dutta (2015). "Deconstructing Universalism: Tagore's Vision of Humanity". In: South Asian Review, 36:2, 193 (footnote nr. 22). DOI: 10.1080/02759527.2015.11933024

- ^ Dracott, Alice Elizabeth. Simla Village Tales, or Folk Tales from the Himalayas. England, London: John Murray. 1906. pp. 6-12.

- ^ Thanapol (Lamduan) Chadchaidee. Fascinating Folktales of Thailand. BangkokBooks, 2011. 121ff (tale nr. 25)

- ^ "Champa Si Ton | Southeast Asia Digital Library".

- ^ Sasorith, Issara Katay; Lucas, Alice. Four Champa Trees. A Traditional Laotian Folktale Told in English and Lao and Teacher Discussion Guide. San Francisco, CA: Voices of Liberty, 1990. pp. 5-15.

- ^ Aung Maung Htin. Burmese Folk-Tales. Oxford University Press. 1948. pp. 112-124.

- ^ Classic Folk Tales from Around the World. Vol. 2. DC Books. pp. 37-45. ISBN 978-81-264-6909-3.

- ^ Carrière, Joseph Médard. Tales From the French Folk-lore of Missouri. Evanston: Northwestern university, 1937. pp. 177-182.

- ^ Vaitkevičienė, Daiva (2013). "Paukštė, kylanti iš pelenų: pomirtinis persikūnijimas pasakose" [The Bird Rising from the Ashes: Posthumous Transformations in Folktales]. Tautosakos darbai (in Lithuanian) (XLVI): 97. ISSN 1392-2831.

- ^ Pitrè, Giuseppe. Fiabe, novelle e racconti popolari siciliani Vol. I. Biblioteca delle tradizioni popolari siciliane Vol. 4. L. Pedone-Lauriel. 1875. pp. 328-329.

- ^ Hartland, Edwin Sidney. The legend of Perseus; a study of tradition in story, custom and belief. Volume I: The Supernatural Birth. London: D. Nutt. 1894. p. 187.

- ^ Pitrè, Giuseppe; Zipes, Jack David; Russo, Joseph. The collected Sicilian folk and fairy tales of Giuseppe Pitrè. New York: Routledge, 2013 [2009]. pp. 838-839. ISBN 9781136094347.

- ^ Angelopoulou, Anna; Brouskou, Aigle. CATALOGUE RAISONNE DES CONTES GRECS: TYPES ET VERSIONS AT700-749. ARCHIVES GEORGES A. MÉGAS: CATALOGUE DU CONTE GREC-2. Athenes: CENTRE DE RECHERCHES NÉOHELLÉNIQUES, FONDATION NATIONALE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE, 1995. p. 132 (entry nr. 263). ISBN 960-7138-13-9.

- ^ Angelopoulou, Anna; Brouskou, Aigle. CATALOGUE RAISONNE DES CONTES GRECS: TYPES ET VERSIONS AT700-749. ARCHIVES GEORGES A. MÉGAS: CATALOGUE DU CONTE GREC-2. Athenes: CENTRE DE RECHERCHES NÉOHELLÉNIQUES, FONDATION NATIONALE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE, 1995. p. 131 (entry nr. 256). ISBN 960-7138-13-9.

- ^ Angelopoulou, Anna; Brouskou, Aigle. CATALOGUE RAISONNE DES CONTES GRECS: TYPES ET VERSIONS AT700-749. ARCHIVES GEORGES A. MÉGAS: CATALOGUE DU CONTE GREC-2. Athenes: CENTRE DE RECHERCHES NÉOHELLÉNIQUES, FONDATION NATIONALE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE, 1995. p. 129 (entry nr. 247). ISBN 960-7138-13-9.

- ^ Alexiou, Margaret. After Antiquity: Greek Language, Myth, and Metaphor. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. 2002. pp. 224-225. ISBN 0-8014-3301-0.

- ^ "A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers". In: Ispirescu, Petre. The foundling prince, & other tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1917. pp. 65-84. [2]

- ^ Pop-Reteganul, Ion. (in Romanian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ "The Wonderful Boys", or "The Wondrous Lads". In: Wratislaw, Albert Henry. Sixty Folk-Tales from Exclusively Slavonic Sources. London: Elliot Stock. 1889. [3]

- ^ The Golden-haired Twins. In: Mijatovich, Elodie Lawton & Denton, William. London: W. Isbister & Co. 1874. pp. 238-247.

- ^ "The Golden-Haired Twins". In: Petrovitch, Woislav M.; Karadzhic, Vuk Stefanovic. Hero tales and legends of the Serbians. New York: Frederick A. Stokes company. [1915] pp. 353-361

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes (1899). "It all comes to light". Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. pp. 67–70.

- ^ "The Count's Evil Mother" (O grofu i njegovoj zloj materi), a Croatian tale from the Karlovac area, collected by Jozo Vrkić, in Hrvatske bajke. Zabreg: Glagol, 1997. The tale first published in written form by Rudolf Strohal.

- ^ "Vom Grafen und seiner bösen Mütter". In: Berneker, Erich Karl. Slavische Chrestomathie mit Glossaren. Strassburg K.J. Trübner. 1902. pp. 226-229.

- ^ "Tri Sultanije i Sultan". In: Buturovic, Djenana i Lada. Antologija usmene price iz BiH/ novi izbor. SA: Svjetlost, 1997.

- ^ Sîrf, Vitalii. "Legăturile reciproce şi paralelele folclorice moldo-găgăuze (în baza materialului basmului)". In: Revista de Etnologie şi Culturologie. 2016, nr. 20, pp. 107-108. ISSN 1857-2049.

- ^ "Болгарские народные сказки" [Bulgarian Folk Tales]. Moscow: Государственное издательство художественной литературы. 1951. pp. 80-84.

- ^ "Zlati Bratkovia". In: Dobšinský, Pavol. Prostonárodnie slovenské povesti. Sešit 2. Turč. Sv. Martin: Tlačou kníhtlač. účast. spolku. - Nákladom vydavatelovým. 1880. pp. 64-70. [4]

- ^ "Zlati Bratkovia". In: Dobšinský, Pavol. Prostonárodnie slovenské povesti. Sešit 5. Turč. Sv. Martin: Tlačou kníhtlač. účast. spolku. - Nákladom vydavatelovým. 1881. pp. 35-40. [5]

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II, Volume 2. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2015. ISBN 978-1-62846-094-0 Notes on tale nr. 287.

- ^ "Die beiden Goldkinder". Haltrich, Josef. Deutsche Volksmärchen aus dem Sachsenlande in Siebenbürgen. Wien: Verlag von Carl Graeser, 1882. p. 1.

- ^ Kovács, Ágnes. "TIPOLOGIA BASMELOR LUI TEODOR ŞIMONCA". In: Hoţopan, Alexandru. împăratu Roşu şi îm păratu Alb (Poveştile lui Teodor Şimonca). Budapesta: Editura didactică, 1982. pp. 218-219. ISBN 9631762823.

- ^ Sandu Timoc, Cristea. Poveşti populare româneşti. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1988. p. x.

- ^ Зуева, Т. В. "Древнеславянская версия сказки "Чудесные дети" ("Перевоплощение светоносных близнецов")". In: Русская речь. 2000. № 2, pp. 98-99.

- ^ Зуева, Т. В. "Древнеславянская версия сказки "Чуд��сные дети" ("Перевоплощение светоносных близнецов")". In: Русская речь. 2000. № 2, p. 100.

- ^ Зуева, Т. В. "Древнеславянская версия сказки "Чудесные дети" ("Перевоплощения светоносных близнецов")". In: Русская речь. 2000. № 3, pp. 91-93.

- ^ Fomin, Maxim. "East meets West in the Land of Fairies and Leprechauns: Translation, Adaptation, and Dissemination of ATU 707 in the 19th–20th century Ireland". In: ՈՍԿԵ ԴԻՎԱՆ – Հեքիաթագիտական հանդես [Voske Divan – Journal of fairy-tale studies]. 6, 2019, pp. 17–19, 22.

- ^ Vaitkevičienė, Daiva (2013). "Paukštė, kylanti iš pelenų: pomirtinis persikūnijimas pasakose" [The Bird Rising from the Ashes: Posthumous Transformations in Folktales]. Tautosakos darbai (in Lithuanian) (XLVI): 90–97. ISSN 1392-2831.

- ^ Kerbelyte, Bronislava. "Litovskie Narodnye Skazki". Moskva: Forum, Neolit, 2015. p. 244. ISBN 978-5-91134-887-8.

- ^ Arājs, Kārlis; Medne, A. Latviešu pasaku tipu rādītājs. Zinātne, 1977. p. 113.

- ^ Haboucha, Reginetta. Types and Motifs of the Judeo-Spanish Folktales (RLE Folklore). Routledge. 2021 [1992]. pp. 152-154. ISBN 9781317549352.

- ^ Die goldenen kinder. In: Walachische Märchen. Arthur und Albert Schott. Stuttgart und Tübingen: J. C. Cotta'scher Verlag. 1845. pp. 121-125.

- ^ "Die goldenen Kinder". In: Schott, Arthur und Albert. Rumänische Volkserzählungen aus dem Banat. Bukarest: Kriterion, 1975. pp. 49-54.

- ^ Sirte-Margarita. In: Murray, Eustace Clare Grenville. Doĭne: Or, the National Songs and Legends of Roumania. Smith, Elder. 1854. pp. 106-110.

- ^ Kovács Ágnes. Szegény ember okos leánya: Román népmesék. Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó. 1957. pp. 24-42.

- ^ Obert, Franz. "Romänische Märchen und Sagen aus Siebenbürgen". In: Das Ausland. Vol. 31. Stuttgart; München; Augsburg; Tübingen: Verlag Cotta. 1858. p. 118.

- ^ Sandu Timoc, Cristea. Poveşti populare româneşti. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1988. p. x.

- ^ Sandu Timoc, Cristea. Poveşti populare româneşti. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1988. pp. 182-186, 408.

- ^ Sandu Timoc, Cristea. Poveşti populare româneşti. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1988. pp. 186-189, 407.

- ^ Беларуская міфалогія: Энцыклапедычны слоўнік [Belarusian mythology: Encyclopedic dictionary]. С. Санько [і інш.]; склад. І. Клімковіч. Мінск: Беларусь, 2004. pp. 575-576. ISBN 985-01-0473-2.

- ^ Bódis, Zoltán. Storytelling: Performance, Presentations and Sacral Communication. In: Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 7 (2). Estonian Literary Museum, Estonian National Museum, University of Tartu. 2013. pp. 22. ISSN 2228-0987 (online)

- ^ Arnold Ipolyi. Ipolyi Arnold népmesegyüjteménye (Népköltési gyüjtemény 13. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvénytársualt Tulajdona. 1914. pp. 274-276.

- ^ János Erdélyi. Magyar népmesék. Pest: Heckenast Gusztáv Sajátja. 1855. pp. 42-47.

- ^ Antal Horger. Hétfalusi csángó népmesék (Népköltési gyüjtemény 10. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvénytársulat Tulajdona. 1908. pp. 112-116.

- ^ Róna-Sklarek, Elisabet. Ungarische Volksmärchen. Neue Folge. Leipzig: Dieterich. 1909. pp. 82-86.

External links[]

- Original text of the fairy tale at Wikisource (in Romanian)

- Doi feți cu stea în frunte at Project Gutenberg

- A két aranyhajú fiú at IMDb

- Romanian fairy tales

- Fictional princes

- Fictional twins

- Twins in fiction

- Fiction about shapeshifting

- Romanian mythology

- Fictional emperors and empresses

- Infanticide