Quebec

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Quebec | |

|---|---|

Province | |

Flag | |

| Motto(s): Je me souviens (French: "I remember") | |

| Coordinates: 52°N 72°W / 52°N 72°WCoordinates: 52°N 72°W / 52°N 72°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Confederation | July 1, 1867 (1st, with Ontario, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick) |

| Capital | Quebec City |

| Largest city | Montreal |

| Largest metro | Greater Montreal |

| Government | |

| • Type | Constitutional monarchy |

| • Body | Government of Quebec |

| • Lieutenant Governor | J. Michel Doyon |

| • Premier | François Legault (CAQ) |

| Legislature | National Assembly of Quebec |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 78 of 338 (23.1%) |

| Senate seats | 24 of 105 (22.9%) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,542,056 km2 (595,391 sq mi) |

| • Land | 1,365,128 km2 (527,079 sq mi) |

| • Water | 176,928 km2 (68,312 sq mi) 11.5% |

| Area rank | Ranked 2nd |

| 15.4% of Canada | |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 8,164,361 [1] |

| • Estimate (2021 Q2) | 8,585,523 [2] |

| • Rank | Ranked 2nd |

| • Density | 5.98/km2 (15.5/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | in English: Quebecer or Quebecker, in French: Québécois (m)[3] Québécoise (f)[3] |

| Official languages | French[4] |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Total (2015) | C$380.972 billion[5] |

| • Per capita | C$46,126 (10th) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2018) | 0.908[6] — Very high (5th) |

| Time zones | |

| most of the province | UTC−05:00 (Eastern Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 |

| Magdalen Islands and Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation | UTC−04:00 (Atlantic Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−03:00 |

| east of the Natashquan River | UTC−04:00 (Atlantic Time Zone) |

| Postal abbr. | QC[7] |

| Postal code prefix | G, H, J |

| ISO 3166 code | CA-QC |

| Flower | Blue flag iris[8] |

| Tree | Yellow birch[8] |

| Bird | Snowy owl[8] |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

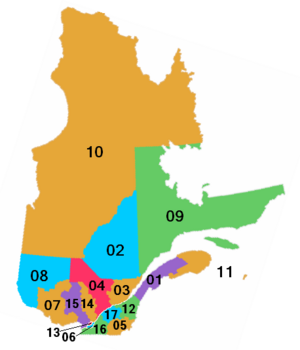

Quebec (/kəˈbɛk/, sometimes /kwəˈbɛk/; French: Québec [kebɛk] (![]() listen))[9] is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. Quebec is the largest province by area, at 1,542,056 km2 (595,391 sq mi), and the second-largest by population, with 8,164,361 people. Much of the population live in urban areas along the St. Lawrence River, between the most populous city, Montreal, and the province's capital city, Quebec City. Quebec is the home of the Québécois, recognized as a nation by both the provincial and federal governments. Located in Central Canada, the province shares land borders with Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast, and a coastal border with Nunavut; it also borders the U.S. states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York to the south.

listen))[9] is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. Quebec is the largest province by area, at 1,542,056 km2 (595,391 sq mi), and the second-largest by population, with 8,164,361 people. Much of the population live in urban areas along the St. Lawrence River, between the most populous city, Montreal, and the province's capital city, Quebec City. Quebec is the home of the Québécois, recognized as a nation by both the provincial and federal governments. Located in Central Canada, the province shares land borders with Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast, and a coastal border with Nunavut; it also borders the U.S. states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York to the south.

Quebec's official language is French, with 94.6% of the province's population reporting knowledge of the language. Québécois French is the local variety, and there are 17 regional accents deriving from it. Among other things, Quebec is well-known for producing nearly 72% of the world's maple syrup, for its comedy, and for making hockey one of the most popular sports in Canada. It is also renowned for its unique and vibrant culture; the province has its own celebrities, and produces its own literature, music/songs, films, TV shows, festivals, folklore, art, and more. Moreover, it has its own cuisine and national symbols.

Between 1534 and 1763, Quebec was called Canada and was the most developed colony in New France. Following the Seven Years' War, however, Quebec became a British colony in the British Empire: first as the Province of Quebec (1763–1791), then Lower Canada (1791–1841), and lastly Canada East (1841–1867), as a result of the Lower Canada Rebellion. It was, finally, confederated with Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick in 1867, beginning the Confederation of Canada. Until the early 1960s, the Catholic Church played a large role in the development of social and cultural institutions in Quebec. However, the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s-1980s increased the role of the Government of Quebec in controlling political, social, and future developments of the state of Quebec.

The Constitution Act, 1867 incorporated the present-day Government of Quebec, which functions within the context of a Westminster system and is both a liberal democracy and a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Premier of Quebec, presently François Legault, acts as head of government and holds office by virtue of commanding the confidence of the elected National Assembly. Québécois political culture mostly differs on a nationalist-vs-federalist continuum, rather than a left-vs-right continuum. Quebec independence debates, in particular, have played a large role in politics. A referendum on sovereignty-association was held in 1980, and one on independence was held in 1995.

Quebec society's cohesion and specificity is based on three of its unique statutory documents: the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, the Charter of the French Language, and the Civil Code of Quebec. Furthermore, unlike in the rest of Canada, law in Quebec is mixed: private law is exercised under a civil-law system, while public law is exercised under a common-law system. Its economy is diversified and post-industrial; sectors of the knowledge economy such as aerospace, information and communication technologies, biotechnology, and the pharmaceutical industry play leading roles. Quebec's substantial natural resources, notably exploited in hydroelectricity, forestry, and mining, have also long been a mainstay. The province's 2018 output was CA$439.3 billion, making it the second-largest Canadian province or territory by GDP.

Etymology

The name Québec comes from the Algonquin[10] word kébec, meaning 'where the river narrows'. The name originally referred to the area around Quebec City where the Saint Lawrence River narrows to a cliff-lined gap. Early variations in the spelling of the name included Québecq (Levasseur, 1601) and Kébec (Lescarbot, 1609).[11] French explorer Samuel de Champlain chose the name Québec in 1608 for the colonial outpost he would use as the administrative seat for the French colony of New France.[12]

Geography

Located in the eastern part of Canada, and (from a historical and political perspective) part of Central Canada, Quebec occupies a territory nearly three times the size of France or Texas, and much closer to the size of Alaska. As is the case with Alaska, most of the land in Quebec is very sparsely populated.[13] Its topography is very different from one region to another due to the varying composition of the ground, the climate (latitude and altitude), and the proximity to water. The Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands and the Appalachians are the two main topographic regions in southern Quebec, while the Canadian Shield occupies most of central and northern Quebec.[14]

Hydrography

Quebec has one of the world's largest reserves of fresh water,[15] occupying 12% of its surface.[16] It has 3% of the world's renewable fresh water, whereas it has only 0.1% of its population.[17] More than half a million lakes,[15] including 30 with an area greater than 250 km2 (97 sq mi), and 4,500 rivers[15] pour their torrents into the Atlantic Ocean, through the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Arctic Ocean, by James, Hudson, and Ungava bays. The largest inland body of water is the Caniapiscau Reservoir, created in the realization of the James Bay Project to produce hydroelectric power. Lake Mistassini is the largest natural lake in Quebec.[18]

The Saint Lawrence River has some of the world's largest sustaining inland Atlantic ports at Montreal (the province's largest city), Trois-Rivières, and Quebec City (the capital). Its access to the Atlantic Ocean and the interior of North America made it the base of early French exploration and settlement in the 17th and 18th centuries. Since 1959, the Saint Lawrence Seaway has provided a navigable link between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes. Northeast of Quebec City, the river broadens into the world's largest estuary, the feeding site of numerous species of whales, fish, and seabirds.[19] The river empties into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. This marine environment sustains fisheries and smaller ports in the Lower Saint Lawrence (Bas-Saint-Laurent), Lower North Shore (Côte-Nord), and Gaspé (Gaspésie) regions of the province. The Saint Lawrence River with its estuary forms the basis of Quebec's development through the centuries. Other notable rivers include the Ashuapmushuan, Chaudière, Gatineau, Manicouagan, Ottawa, Richelieu, Rupert, Saguenay, Saint-François, and Saint-Maurice.

Topography

Quebec's highest point at 1,652 metres (5,420 ft) is Mont d'Iberville, known in English as Mount Caubvick, located on the border with Newfoundland and Labrador in the northeastern part of the province, in the Torngat Mountains.[20] The most populous physiographic region is the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands. It extends northeastward from the southwestern portion of the province along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River to the Quebec City region, limited to the North by the Laurentian Mountains and to the South by the Appalachians. It mainly covers the areas of the Centre-du-Québec, Laval, Montérégie and Montreal, the southern regions of the Capitale-Nationale, Lanaudière, Laurentides, Mauricie and includes Anticosti Island, the Mingan Archipelago,[21] and other small islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence lowland forests ecoregion.[22] Its landscape is low-lying and flat, except for isolated igneous outcrops near Montreal called the Monteregian Hills, formerly covered by the waters of Lake Champlain. The Oka hills also rise from the plain. Geologically, the lowlands formed as a rift valley about 100 million years ago and are prone to infrequent but significant earthquakes.[14] The most recent layers of sedimentary rock were formed as the seabed of the ancient Champlain Sea at the end of the last ice age about 14,000 years ago.[23] The combination of rich and easily arable soils and Quebec's relatively warm climate makes this valley the most prolific agricultural area of Quebec province. Mixed forests provide most of Canada's springtime maple syrup crop. The rural part of the landscape is divided into narrow rectangular tracts of land that extend from the river and date back to settlement patterns in 17th century New France.

More than 95% of Quebec's territory lies within the Canadian Shield.[24] It is generally a quite flat and exposed mountainous terrain interspersed with higher points such as the Laurentian Mountains in southern Quebec, the Otish Mountains in central Quebec and the Torngat Mountains near Ungava Bay. The topography of the Shield has been shaped by glaciers from the successive ice ages, which explains the glacial deposits of boulders, gravel and sand, and by sea water and post-glacial lakes that left behind thick deposits of clay in parts of the Shield. The Canadian Shield also has a complex hydrological network of perhaps a million lakes, bogs, streams and rivers. It is rich in the forestry, mineral and hydro-electric resources that are a mainstay of the Quebec economy. Primary industries sustain small cities in regions of Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, and Côte-Nord.

The Labrador Peninsula is covered by the Laurentian Plateau (or Canadian Shield), dotted with mountains such as Otish Mountains. The Ungava Peninsula is notably composed of D'Youville mountains, Puvirnituq mountains and Pingualuit crater. While low and medium altitude peak from western Quebec to the far north, high altitudes mountains emerge in the Capitale-Nationale region to the extreme east, along its longitude. In the Labrador Peninsula portion of the Shield, the far northern region of Nunavik includes the Ungava Peninsula and consists of flat Arctic tundra inhabited mostly by the Inuit. Further south lie the subarctic taiga of the Eastern Canadian Shield taiga ecoregion and the boreal forest of the Central Canadian Shield forests, where spruce, fir, and poplar trees provide raw materials for Quebec's pulp and paper and lumber industries. Although the area is inhabited principally by the Cree, Naskapi, and Innu First Nations, thousands of temporary workers reside at Radisson to service the massive James Bay Hydroelectric Project on the La Grande and Eastmain rivers. The southern portion of the shield extends to the Laurentians, a mountain range just north of the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands, that attracts local and international tourists to ski hills and lakeside resorts.

The Appalachian region of Quebec has a narrow strip of ancient mountains along the southeastern border of Quebec. The Appalachians are actually a huge chain that extends from Alabama to Newfoundland. In between, it covers in Quebec near 800 km (497 mi), from the Montérégie hills to the Gaspé Peninsula. In western Quebec, the average altitude is about 500 metres (1,600 ft), while in the Gaspé Peninsula, the Appalachian peaks (especially the Chic-Choc) are among the highest in Quebec, exceeding 1,000 metres (3,300 ft).

Climate

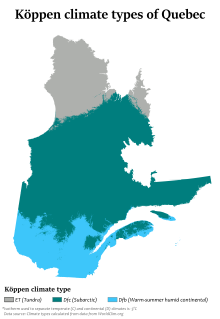

In general, the climate of Quebec is cold and humid.[25] The climate of the province is largely determined by its latitude, maritime and elevation influences.[25] According to the Köppen climate classification, Quebec has three main climate regions.[25] Southern and western Quebec, including most of the major population centres and areas south of 51oN, have a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with four distinct seasons having warm to occasionally hot and humid summers and often very cold and snowy winters.[25][26] The main climatic influences are from western and northern Canada and move eastward, and from the southern and central United States that move northward. Because of the influence of both storm systems from the core of North America and the Atlantic Ocean, precipitation is abundant throughout the year, with most areas receiving more than 1,000 mm (39 in) of precipitation, including over 300 cm (120 in) of snow in many areas.[27] During the summer, severe weather patterns (such as tornadoes and severe thunderstorms) occur occasionally.[28] Most of central Quebec, ranging from 51 to 58 degrees North has a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc).[25] Winters are long, very cold, and snowy, and among the coldest in eastern Canada, while summers are warm but very short due to the higher latitude and the greater influence of Arctic air masses. Precipitation is also somewhat less than farther south, except at some of the higher elevations. The northern regions of Quebec have an arctic climate (Köppen ET), with very cold winters and short, much cooler summers.[25] The primary influences in this region are the Arctic Ocean currents (such as the Labrador Current) and continental air masses from the High Arctic.

The four calendar seasons in Quebec are spring, summer, autumn and winter, with conditions differing by region. They are then differentiated according to the insolation, temperature, and precipitation of snow and rain.[29]

At Quebec City, the length of the daily sunshine varies from 8:37 hrs in December to 15:50 hrs in June; the annual variation is much greater (from 4:54 to 19:29 hrs) at the northern tip of the province.[30] From temperate zones to the northern territories of the Far North, the brightness varies with latitude, as well as the Northern Lights and midnight sun.

Quebec is divided into four climatic zones: arctic, subarctic, humid continental and East maritime. From south to north, average temperatures range in summer between 25 and 5 °C (77 and 41 °F) and, in winter, between −10 and −25 °C (14 and −13 °F).[31][32] In periods of intense heat and cold, temperatures can reach 35 °C (95 °F) in the summer[33] and −40 °C (−40 °F) during the Quebec winter,[33] They may vary depending on the Humidex or Wind chill. The all time record high was 40.0 °C (104.0 °F) and the all time record low was −51.0 °C (−59.8 °F).[34]

The all-time record of the greatest precipitation in winter was established in winter 2007–2008, with more than five metres[35] of snow in the area of Quebec City, while the average amount received per winter is around three metres.[36] March 1971, however, saw the "Century's Snowstorm" with more than 40 cm (16 in) in Montreal to 80 cm (31 in) in Mont Apica of snow within 24 hours in many regions of southern Quebec. Also, the winter of 2010 was the warmest and driest recorded in more than 60 years.[37]

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal | 26/16 | 79/61 | −5/−14 | 22/7 |

| Gatineau | 26/15 | 79/60 | −6/−15 | 21/5 |

| Quebec City | 25/13 | 77/56 | −8/−18 | 17/0 |

| Trois-Rivières | 25/14 | 78/58 | −7/−17 | 19/1 |

| Sherbrooke | 24/11 | 76/53 | −6/−18 | 21/0 |

| Saguenay | 24/12 | 75/54 | −10/−21 | 14/−6 |

| Matagami | 23/9 | 73/48 | −13/−26 | 8/−16 |

| Kuujjuaq | 17/6 | 63/43 | −20/−29 | −4/−20 |

| Inukjuak | 13/5 | 56/42 | −21/−28 | −6/−19 |

Wildlife

The large land wildlife is mainly composed of the white-tailed deer, the moose, the muskox, the caribou (reindeer), the American black bear and the polar bear. The average land wildlife includes the cougar, the coyote, the eastern wolf, the bobcat, the Arctic fox, the fox, etc. The small animals seen most commonly include the eastern grey squirrel, the snowshoe hare, the groundhog, the skunk, the raccoon, the chipmunk and the Canadian beaver.

Biodiversity of the estuary and gulf of Saint Lawrence River[39] consists of an aquatic mammal wildlife, of which most goes upriver through the estuary and the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park until the Île d'Orléans (French for Orleans Island), such as the blue whale, the beluga, the minke whale and the harp seal (earless seal). Among the Nordic marine animals, there are two particularly important to cite: the walrus and the narwhal.[40]

Inland waters are populated by small to large fresh water fish, such as the largemouth bass, the American pickerel, the walleye, the Acipenser oxyrinchus, the muskellunge, the Atlantic cod, the Arctic char, the brook trout, the Microgadus tomcod (tomcod), the Atlantic salmon, the rainbow trout, etc.[41]

Among the birds commonly seen in the southern inhabited part of Quebec, there are the American robin, the house sparrow, the red-winged blackbird, the mallard, the common grackle, the blue jay, the American crow, the black-capped chickadee, some warblers and swallows, the starling and the rock pigeon, the latter two having been introduced in Quebec and are found mainly in urban areas.[42] Avian fauna includes birds of prey like the golden eagle, the peregrine falcon, the snowy owl and the bald eagle. Sea and semi-aquatic birds seen in Quebec are mostly the Canada goose, the double-crested cormorant, the northern gannet, the European herring gull, the great blue heron, the sandhill crane, the Atlantic puffin and the common loon.[43] Many more species of land, maritime or avian wildlife are seen in Quebec, but most of the Quebec-specific species and the most commonly seen species are listed above.

Some livestock have the title of "Québec heritage breed", namely the Canadian horse, the Chantecler chicken and the Canadian cow.[44] Moreover, in addition to food certified as "organic", Charlevoix lamb is the first local Quebec product whose geographical indication is protected.[45] Livestock production also includes the pig breeds Landrace, Duroc and Yorkshire[46] and many breeds of sheep[47] and cattle.

The Wildlife Foundation of Quebec and the Data Centre on Natural Heritage of Quebec (CDPNQ) (French acronym)[48] are the main agencies working with officers for wildlife conservation in Quebec.

Vegetation

Given the geology of the province and its different climates, there is an established number of large areas of vegetation in Quebec. These areas, listed in order from the northernmost to the southernmost are: the tundra, the taiga, the Canadian boreal forest (coniferous), mixed forest and Deciduous forest.[24]

On the edge of the Ungava Bay and Hudson Strait is the tundra, whose flora is limited to a low vegetation of lichen with only less than 50 growing days a year. The tundra vegetation survives an average annual temperature of −8 °C (18 °F). The tundra covers more than 24% of the area of Quebec.[24] Further south, the climate is conducive to the growth of the Canadian boreal forest, bounded on the north by the taiga.

Not as arid as the tundra, the taiga is associated with the sub-Arctic regions of the Canadian Shield[49] and is characterized by a greater number of both plant (600) and animal (206) species, many of which live there all year. The taiga covers about 20% of the total area of Quebec.[24] The Canadian boreal forest is the northernmost and most abundant of the three forest areas in Quebec that straddle the Canadian Shield and the upper lowlands of the province. Given a warmer climate, the diversity of organisms is also higher, since there are about 850 plant species and 280 vertebrates species. The Canadian boreal forest covers 27% of the area of Quebec.[24] The mixed forest is a transition zone between the Canadian boreal forest and deciduous forest. By virtue of its transient nature, this area contains a diversity of habitats resulting in large numbers of plant (1000) and vertebrates (350) species, despite relatively cool temperatures. The ecozone mixed forest covers 11.5% of the area of Quebec and is characteristic of the Laurentians, the Appalachians and the eastern lowlands forests.[49] The third most northern forest area is characterized by deciduous forests. Because of its climate (average annual temperature of 7 °C [45 °F]), it is in this area that one finds the greatest diversity of species, including more than 1600 vascular plants and 440 vertebrates. Its relatively long growing season lasts almost 200 days and its fertile soils make it the centre of agricultural activity and therefore of urbanization of Quebec. Most of Quebec's population lives in this area of vegetation, almost entirely along the banks of the Saint Lawrence. Deciduous forests cover approximately 6.6% of the area of Quebec.[24]

The total forest area of Quebec is estimated at 750,300 km2 (289,700 sq mi).[50] From the Abitibi-Témiscamingue to the North Shore, the forest is composed primarily of conifers such as the Abies balsamea, the jack pine, the white spruce, the black spruce and the tamarack. Some species of deciduous trees such as the yellow birch appear when the river is approached in the south. The deciduous forest of the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands is mostly composed of deciduous species such as the sugar maple, the red maple, the white ash, the American beech, the butternut (white walnut), the American elm, the basswood, the bitternut hickory and the northern red oak as well as some conifers such as the eastern white pine and the northern whitecedar. The distribution areas of the paper birch, the trembling aspen and the mountain ash cover more than half of Quebec territory.[51]

Territorial evolution

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

- Territorial evolution of Quebec

The New France colony of Canada (in blue) in 1650.

Canada at its fullest extent after 1713.

North America in 1750, before the Seven Years' War.

The Province of Quebec from 1763 to 1783.

Lower Canada from 1791 to 1841. (Patriots' War in 1837)

The Province of Canada in 1850. (Canada East in green and Canada West in orange)

Quebec from 1867 to 1927. (Confederation in 1867)

Quebec today. Quebec (in blue) has a border dispute with Labrador (in red).

In 1534, Quebec's coasts off the Saint Lawrence River and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence were explored and claimed as French territory by Jacques Cartier, who called the territory "Canada". Between 1534 and 1603, with exploration and expansion, Canada's territory grew to encompass the coasts of the Saint Lawrence River, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, as well as the entirety of Prince Edward Island. Between 1603 and 1673, due to westward exploration, expansion and conflicts with the England, Canada became composed of the coasts of the Saint Lawrence River, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and of the Great Lakes, as well as southern Ontario and northern New England. In 1663, the Company of New France ceded Canada to the King, Louis XIV, who then proclaimed Canada a royal province of France and created the Sovereign Council of New France to administer the new province. Between 1673 and 1741, due to more westward exploration and conflicts with Great Britain, Canada grew to its largest size and was now composed of the coasts of the Saint Lawrence River, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Labrador and the Great Lakes, as well as southern Ontario, southern Manitoba and the north-eastern Midwest.[52]

In 1760, the British conquered Canada and the Canadiens were put under a British military regime until the end of the Seven Years' War. In 1763, the Treaty of Paris formally transferred Canada to Britain. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 created the new Province of Quebec out of the conquered territory. Quebec now only encompassed the banks of the Saint Lawrence River and Anticosti Island. However, in 1774, the Quebec Act restored Quebec's territory to roughly the size before the conquest.[53] Around this time, instructions were issued to the colony of Newfoundland, requiring it to supervise Labrador's coasts, even though Labrador was part of the Province of Quebec, not Newfoundland. In 1783, the new Treaty of Paris, which recognised the independence of the United States, ceded the territories south of the Great Lakes to the United States, greatly reducing the Province of Quebec's size.[54] In 1791, the Constitutional Act divided the Province of Quebec into the primarily French-speaking Lower Canada (now Quebec) and the primarily English-speaking Upper Canada (now Ontario). Lower Canada's lands consisted of the coasts of the Saint Lawrence River, Labrador and Anticosti Island, with the territory extending north to the boundary of Rupert's Land, and extending south, east and west to the borders with the US, New Brunswick, and Upper Canada. By 1809, the government of Newfoundland was no longer willing to supervise the coasts of Labrador. To solve this issue, and as a result of lobbying in London, the British government assigned the coasts of Labrador to the colony of Newfoundland. The inland border between the jurisdiction of Lower Canada and Newfoundland was not well-defined.[55] From 1837 to 1838, the Lower Canada Rebellion occurred. In 1840, the British Parliament decided that a proper response to the Lower Canada Rebellion was to try to assimilate the French-speaking inhabitants of Lower Canada by rejoining Lower Canada and Upper Canada, creating the Province of Canada. Lower Canada was renamed Canada East and Upper Canada was renamed Canada West.[56]

In 1867, the Confederation of Canada took place. The Province of Canada was divided into two new provinces, Quebec and Ontario, based on the former boundaries of Lower Canada and Upper Canada.[57] In 1898, the Canadian Parliament enacted the Quebec Boundary Extension Act, 1898, which gave Quebec a part of Rupert's Land, which the Dominion of Canada had bought from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870.[58] This Act expanded the boundaries of Quebec northward. In 1912, the Canadian Parliament enacted the Quebec Boundaries Extension Act, 1912, which gave Quebec another part of Rupert's Land: the District of Ungava.[59] This extended the borders of Quebec northward all the way to the Hudson Strait. In 1927, the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council drew a clear border between northeast Quebec and south Labrador. However, the Quebec government did not recognize the ruling of this council, resulting in a boundary dispute.

Today, Quebec occupies a total surface area of approximately 1,542,056 km2 (595,391 sq mi) and its border is roughly 12,000 km (7,500 mi) long. The province has land borders with Labrador, New Brunswick, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York and Ontario. Quebec also has sea borders with Nunavut. The Quebec-Labrador boundary dispute is still ongoing today, leading some to comment that Quebec's borders are the most imprecise in the Americas.[60]

History

It has been suggested that this article be split into articles titled History of Quebec and Timeline of Quebec history. (Discuss) (July 2021) |

Prehistory and protohistory

Indigenous peoples

During the last ice age, 20,000 years ago, nomads from Asia very gradually made their way to the Bering Strait, crossed it and reached America. From there, they and their descendants then populated the different regions of the continent. The first humans who established themselves on the lands of Quebec arrived there after the Laurentide Ice Sheet melted, roughly 11,000 years ago.[61]

From the first people who settled on the lands of Quebec, various ethnocultural groups emerged. They can today be grouped into eleven indigenous peoples: the Inuit and the ten Amerindian nations of the Abenakis, the Algonquins (or Anichinabés), the Attikameks, the Cree (or Eeyou), the Huron-Wendat, the Wolastoqiyik (or Etchemins), the Micmacs, the Mohawks (or Iroquois), the Innu (or Montagnais) and the Naskapis.[62] In the past, other groups were also present. For example, the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, a branch of the Iroquois who lived more settled lives in the Saint Lawrence Valley, who appear to have been supplanted by the Mohawks.[63] The Dorsets, a people who inhabited Quebec's northern regions, seem to have been supplanted by the Inuit.[64]

At the time of the European explorations of the 1500s, it was known that these groups sometimes traded and/or warred with each other. It was also known that Algonquians organized into seven political entities and lived nomadic lives based on hunting, gathering, and fishing on the Canadian Shield and Appalachian Mountains.[65] Inuit, on the other hand, fished and hunted whales and seals in the harsh Arctic climate along the coasts of Hudson and Ungava Bay.[66]

European explorations

The first confirmed contact between pre-Columbian civilizations and European explorers occurred in the 10th century, when the Icelandic Viking Leif Erikson explored some of the coasts of Newfoundland, Baffin Island, Greenland and Labrador.[67] From the 15th to 16th century, Basques, Bretons and Normans also occasionally traveled to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to exploit the plentiful fish.[68]

In the 14th century, the Byzantine Empire fell. For the Christian West, this made trade with the Far East, usually for things like spices and gold, more difficult because sea routes were now under the control of less cooperative Arab and Italian merchants.[69] As such, in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Spanish and Portuguese, and then the English and French, began to search for a new sea route. One method involved trying to bypass Africa. But, since the Europeans knew that the Earth was round, a second method involved traveling continuously West to circle the Earth. At the time, the Old World was not aware of the continent of America's existence and that it would be blocking the way. As such, in 1492, the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus set sail West and became the first European explorer to discover America. Columbus' discovery became the cataclysm for the European exploration movement.

France eventually wanted to find a way to bypass North America and reach China, like Magellan had done with South America by traveling under Cape Horn. Around 1522–1523, the Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano persuaded King Francis I of France to commission an expedition to find a western route to Cathay (China). Therefore, King Francis I launched a maritime expedition in 1524, led by Giovanni da Verrazzano, to search for the Northwest Passage. Though this expedition was unsuccessful, it established the name "New France" for Northeastern North America.[70]

In his first expedition ordered from the Kingdom of France, Jacques Cartier became the first European explorer to discover and map Quebec when he landed in Gaspé on July 24, 1534.[71] The second expedition, in 1535, was bigger and comprised 110 men on three ships: the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine and the Emérillon. That year, Jacques Cartier explored the lands of Stadaconé and decided to name the village and its surrounding territories Canada, because he had heard two young natives use the word kanata ("village" in Iroquois) to describe the location.[72] 16-century European cartographers would quickly adopt this name.[73] Cartier also wrote that he thought he had discovered large amounts of diamonds and gold, but this ended up only being quartz and pyrite. Then, by following what he called the Great River, he traveled West to the Lachine Rapids. There, navigation proved too dangerous for Cartier to continue his journey towards the goal: China. Cartier and his sailors had no choice but to return to Stadaconé and winter there. In the end, Cartier returned to France and took about 10 Native Americans, including the St. Lawrence Iroquoians chief Donnacona, with him. In 1540, Donnacona told the legend of the Kingdom of Saguenay to the King of France. This inspired the king to order a third expedition, this time led by Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval and with the goal of finding the Kingdom of Saguenay. But, it was unsuccessful.[74]

After these expeditions, France mostly abandoned the idea of America for 50 years because of its financial crisis; France was at war with Italy and there were religious wars between Protestants and Catholics.[75]

Around 1580, France became interested in America again, because the fur trade had become important in Europe. France returned to America looking for a specific animal: the beaver. As New France was full of beavers, it became a colonial-trading post where the main activity was the fur trade in the Pays-d'en-Haut.[76] In 1600, Pierre de Chauvin de Tonnetuit founded the first permanent trading post in Tadoussac for expeditions carried out in the Domaine du Roy.[77]

In 1603, Samuel de Champlain travelled to the Saint Lawrence River and, on Pointe Saint-Mathieu, established a defence pact with the Innu, Wolastoqiyik and Micmacs, that would be "a decisive factor in the maintenance of a French colonial enterprise in America despite an enormous numerical disadvantage vis-à-vis the British colonization in the South".[78][79] Thus also began French military support to the Algonquian and Huron peoples in defence against Iroquois attacks and invasions. These Iroquois attacks would become known as the Beaver Wars and would last from the early 1600s to the early 1700s.[80]

New France (1608–1765)

Founding and development of trading posts (1608–1663)

In 1608, Samuel de Champlain[81] returned to the region as head of an exploration party. On July 3, 1608, with the support of King Henri IV, he founded the Habitation de Québec (now Quebec City) on Cap Diamant and made it the capital of New France and all of its regions (which, at the time, were Acadia, Canada and Plaisance in Newfoundland).[82] The settlement was built as a permanent fur trading outpost. First Nations traded their furs for many French goods such as metal objects, guns, alcohol, and clothing.[83] In 1616, the Habitation du Québec became the first permanent establishment of the [84] with the arrival of its two very first settlers: Louis Hébert[85] and Marie Rollet.[86] Several missionary groups arrived in New France after the founding of Québec, like the Recollects in 1615, the Jésuites in 1625 and the Supliciens in 1657.

Coureurs des bois and Catholic missionaries used river canoes to explore the interior of the North American continent.[87] They established fur trading forts on the Great Lakes (Étienne Brûlé 1615), Hudson Bay (Radisson and Groseilliers 1659–60), Ohio River and Mississippi River (La Salle 1682), as well as the Saskatchewan River and Missouri River (de la Verendrye 1734–1738).[88]

In 1612, the Compagnie de Rouen received the royal mandate to manage the operations of New France and the fur trade. In 1621, they were replaced by the Compagnie de Montmorency. Then, in 1627, they were substituted by the Compagnie des Cent-Associés. Shortly after being appointed, the Compagnie des Cent-Associés introduced the Custom of Paris and the seigneurial system to New France. They also forbade settlement in New France by anyone other than Roman Catholics.[89][90]

In 1629, there was the surrender of Quebec, without battle, to English privateers led by David Kirke during the Anglo-French War. Samuel de Champlain argued that the English seizing of the lands was illegal as the war had already ended; he worked to have the lands returned to France. In 1632, the English king agreed to return the lands in exchange for Louis XIII paying his wife's dowry. These terms were signed into law with the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and the lands in Quebec and Acadia were returned to the Compagnie des Cent-Associés.

In 1634, Sieur de Laviolette founded Trois-Rivières at the mouth of the Saint-Maurice River. In 1642, Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve founded Ville-Marie (now Montreal) on Pointe-à-Callière. He chose to found Montreal on an island so that the settlement could be naturally protected against Iroquois invasions.

Many heroes of New France come from this period, such as Dollard des Ormeaux,[91] Guillaume Couture, Madeleine de Verchères and the Canadian Martyrs.

Royal province (1663-1760)

In 1663, King Louis XIV officially made New France into a royal province of France.[92] New France would now be a true colony administered by the Sovereign Council of New France from Québec, and which functioned off triangular trade. A governor-general, assisted by the intendant of New France and the bishop of Québec, would go on to govern Canada (Montreal, Québec, Trois-Rivières and the Pays-d'en-Haut) and its administrative dependencies: Acadia, Louisiana and Plaisance.[93]

The French settlers were mostly farmers and they were known as "Canadiens" or "Habitants". Though there was little immigration,[94] the colony still grew because of the Habitants' high birth rates.[95][96] In 1665, the Carignan-Salières regiment developed the string of fortifications known as the "Valley of Forts" to protect against Iroquois invasions. The Regiment brought along with them 1,200 new men from Dauphiné, Liguria, Piedmont and Savoy.[97] To redress the severe imbalance between single men and women, and boost population growth, King Louis XIV sponsored the passage of approximately 800 young French women (known as les filles du roi) to the colony.[98] In 1666, intendant Jean Talon organized the first census of the colony and counted 3,215 Habitants. Talon also enacted policies to diversify agriculture and encourage births, which, in 1672, had increased the population to 6,700 Canadiens.[99]

In 1686, the Chevalier de Troyes and the Troupes de la Marine seized three northern forts the English had erected on the lands explored by Charles Albanel in 1671 near Hudson Bay.[100] Similarly, in the south, Cavelier de La Salle took for France lands discovered by Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet in 1673 along the Mississippi River. As a result, the colony of New France's territory grew to extend from Hudson Bay all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, and would also encompass the Great Lakes.[101]

In the early 1700s, Governor Callières concluded the Great Peace of Montreal, which not only confirmed the alliance between the Algonquian peoples and New France, but also definitively ended the Beaver Wars.[102] In 1701, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville founded the district of Louisiana and made its administrative headquarter Biloxi. Its headquarter was later moved to Mobile, and then to New Orleans.[103] In 1738, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, extended New France to Lake Winnipeg. In 1742, his voyageur sons, François and Louis-Joseph, crossed the Great Plains and discovered the Rocky Mountains.[104]

From 1688 onwards, the fierce competition between the French Empire and British Empire to control North America's interior and monopolize the fur trade pitted New France and its Indigenous allies against the Iroquois and English -primarily in the Province of New York- in a series of four successive wars called the French and Indian Wars by Americans, and the Intercolonial wars in Quebec.[105] The first three of these wars were King William's War (1688-1697), Queen Anne's War (1702-1713), and King George's War (1744-1748). Many notable battles and exchanges of land took place. In 1690, the Battle of Quebec became the first time Québec's defences were tested. In 1713, following the Peace of Utrecht, the Duke of Orléans ceded Acadia and Plaisance Bay to the Kingdom of Great Britain, but retained Île Saint-Jean, and Île-Royale (Cape Breton Island) where the Fortress of Louisbourg was subsequently erected. These losses were significant since Plaisance Bay was the primary communication route between New France and France, and Acadia contained 5,000 Acadians.[106][107] In the siege of Louisbourg in 1745, the British were victorious, but returned the city to France after war concessions.[108]

Conquest of New France (1754–1763)

The last of the 4 French and Indian Wars was called the Seven Years' War ("The War of the Conquest" in Quebec, The French and Indian War in the US) and lasted from 1754 to 1763.[109][110] In 1754, tensions escalated for control of the Ohio Valley, an area controlled by French fur trade companies but coveted by British fur trade companies. Authorities in New France became more aggressive in their efforts to expel British traders and colonists from the Ohio Valley, and they began construction of a series of fortifications to protect the area.[111] In 1754, George Washington launched a surprise attack in the early morning hours on a group of sleeping Canadien soldiers. It came at a time when no declaration of war had been issued by anyone. This aggressive act, known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen, became the first battle of the Seven Years' War. By 1756, France and Britain were battling the Seven Years' War worldwide. In 1755, the first batch of new French soldiers arrived, commanded by Jean-Armand Dieskau. The latter would go on to fight in the Battle of Lake George, but would be wounded and taken prisoner. Also in 1755, the forceful Deportation of the Acadians was ordered by the Governor Charles Lawrence and Officer Robert Monckton. In 1756, Lieutenant General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm arrived in New France with 3,000 men as reinforcements.[112]

In 1758, on Île-Royale, British General James Wolfe besieged and captured the Fortress of Louisbourg.[113] This allowed him to control access to the Gulf of St. Lawrence through the Cabot Strait. In 1759, he for nearly three months from Île d'Orléans.[114] Then, Wolfe and his men stormed Québec and fought against Montcalm and his men for control of the city in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Both Montcalm and Wolfe died from the battle. The British won on September 13, 1759. Five days later, the king's lieutenant and Lord of Ramezay concluded the Articles of Capitulation of Quebec.

During the spring of 1760, the Chevalier de Lévis, armed with a new garrison from Ville-Marie, besieged Québec and forced the British to entrench themselves during the Battle of Sainte-Foy. However, the loss of the French vessels sent to support and resupply New France after the fall of Québec during the Battle of Restigouche marked the end of France's efforts to try to retake the colony. Then, after the British captured Trois-Rivières, Governor Vaudreuil signed the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal on September 8, 1760.

While awaiting the results of the Seven Years' War,[115] the rest of which was taking place in Europe, New France was put under a led by Governor James Murray.[116] The regime remained from 1760 to 1763. In 1762, Commander Jeffery Amherst ended the French presence in Newfoundland at the Battle of Signal Hill. Two months later, France ceded the western part of Louisiana and the Mississippi River Delta to the Kingdom of Spain via the Treaty of Fontainebleau in an attempt to curb British expansion towards the west of the continent. On February 10, 1763, the Treaty of Paris concluded the war. With the exception of the small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, France ceded its North American possessions to Great Britain in favour of gaining Guadeloupe for its then-lucrative sugar cane industry.[117] Thus, France had put an end to New France and abandoned the remaining 60,000 Canadiens who, as a result, sided with the Catholic clergy, refusing to take an oath to the British Crown.[118]

The rupture from France would provoke a transformation within the descendants of the Canadiens that would eventually result in the birth of a new nation whose development and culture would be founded upon, among other things, ancestral foundations anchored in Northeastern America.[119] This is referenced in O Canada with the passage: “terre de nos aïeux” ("land of our ancestors").[120] What British Commissioner John George Lambton (Lord Durham) would describe in his 1839 report would be the kind of relationship that would reign between the "Two Solitudes" of Canada for a long time: "I found two nations at war within one state; I found a struggle, not of principles, but of races”.[121] Incoming British immigrants would find that Canadiens were as full of national pride as they were, and while these newcomers would see the American territories as a vast ground for colonization and speculation, the Canadiens would regard Quebec as the heritage of their own race - not as a country to colonize, but as a country already colonized.[122]

British North America (1763–1867)

Province of Quebec (1763–1791)

After the British officially acquired Canada in 1763, King George III reorganized the constitution of Canada using the Royal Proclamation.[123] From this point on, the Canadiens were subordinated to the government of the British Empire and circumscribed to a region of St. Lawrence valley called the Province of Quebec. Canadiens were not happy with British rule. Likewise, during the Pontiac Rebellion of 1763, the Amerindian peoples jointly fought against the new order established by the British, and the Boston Tea Party of 1773 marked the culmination of the protest movements in the British American colonies.

With unrest growing in the colonies to the south, which would one day grow into the American Revolution, the British were worried that the Canadiens might also support the growing rebellion. At the time, Canadiens formed the vast majority of the population of the Province of Quebec (more than 99%) and British immigration was not going well. To secure the allegiance of Canadiens to the British crown, Governor James Murray and later Governor Guy Carleton promoted the need for accommodations. This eventually resulted in enactment of the Quebec Act[124] of 1774. This act allowed Canadiens to regain their civil customs, return to the seigneural system, regain certain rights (including the use of the French language), and reappropriate their old territories: Labrador, the Great Lakes, the Ohio Valley, Illinois Country and the Indian Territory. However, the oath of abjuration to the Catholic faith was replaced by an oath of allegiance to the British Crown. The Council for the Affairs of the Province of Quebec was established to admit Canadiens - that is to say faithful Catholics - to civil and governmental functions.[125]

As early as 1774, the Continental Congress of the separatist Thirteen Colonies attempted to rally the Canadiens to its cause. However, its military troops failed to defeat the British counteroffensive during its Invasion of Quebec in 1775. When it came to the idea of rebelling against the British, most Canadiens were neutral, although some patriotic regiments allied themselves with the American revolutionaries in the Saratoga campaign of 1777. When the British Empire recognized the independence of the rebel colonies at the signing of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, it conceded Illinois and the Ohio Valley to the newly formed United States and denoted the 45th parallel as the separation between the British Empire and the US. This drastically reduced the Province of Quebec's size; its southwest borders now ended at the Great Lakes. Then, United Empire Loyalists migrated to the Province of Quebec and populated various regions, including the Niagara Peninsula, the Eastern Townships and Thousand Islands.[126]

Lower Canada and Lower Canada Rebellion (1791–1840)

Dissatisfied with the many rights granted to Canadiens and wanting to use the British legal system they were used to in the American colonies, the immigrant Loyalists from the United States protested to British authorities until the Constitutional Act of 1791 was enacted, dividing the Province of Quebec into two distinct colonies starting from the Ottawa River: Upper Canada to the west (predominantly Anglo-Protestant) and Lower Canada to the east (predominantly Franco-Catholic). Each colony had a parliamentary system based on the principles of the Westminster system. However, the creation of Upper and Lower Canada allowed most Loyalists to live under British laws and institutions, while most Canadiens could maintain their familiar French civil law and the Catholic religion. Furthermore, Governor Haldimand drew Loyalists away from Quebec City and Montreal by offering free land of 200 acres (81 ha) per person on the northern shore of Lake Ontario to anyone willing to swear allegiance to George III. Basically, these colonies were designed with the intent of keeping French-speakers and English-speakers separate.[127]

In 1813, Beauport-native Charles-Michel de Salaberry became a hero by leading the Canadian troops to victory at the Battle of Chateauguay, during the War of 1812. In this battle, 300 Voltigeurs and 22 Amerindians successfully pushed back a force of 7000 Americans. This loss caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence Campaign, their major strategic effort to conquer Canada.

Gradually, the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, who represented the people, came more and more into conflict with the superior authority of the Crown and its appointed representatives. Starting in 1791, the government of Lower Canada was criticized and contested by the Parti canadien. In 1834, the Parti canadien presented its 92 resolutions, a series of political demands which expressed a genuine loss of confidence in the British monarchy. London refused to consider these and, in response, submitted . Discontentment intensified throughout the public meetings of 1837, sometimes being lead by tribunes like Louis-Joseph Papineau. Despite opposition from ecclesiastics, for example Jean-Jacques Lartigue, the Rebellion of the Patriotes began in 1837.[128]

In 1837, Louis-Joseph Papineau and Robert Nelson led residents of Lower Canada to form an armed resistance group called the Patriotes in order to seek an end to the unilateral control of the British governors.[130] They made a Declaration of Independence in 1838, guaranteeing human rights and equality for all citizens without discrimination.[131] Their actions resulted in rebellions in both Lower and Upper Canada. The Patriotes forces were victorious in their first battle, the Battle of Saint-Denis, because the British army was unprepared. However, the Patriotes were unorganized and badly equipped, leading to their loss against the British army in their second battle, the Battle of Saint-Charles, and their defeat in their final battle, the Battle of Saint-Eustache.[132] Following the British's defeat of the Patriotes, the Catholic clergy recovered their moral authority among the people and preached for the cohesion and development of the nation in the fields of education, health and civil society.

As access to new lands remained problematic because they were still monopolized by the Clique du Château, an exodus of Canadiens towards New England began and went on for the next one hundred years. This phenomenon is known as the Grande Hémorragie and greatly threatened the survival of the Canadien nation.[133] The massive British immigration ordered from London that soon followed the failed rebellion would only serve to further compound this problem. In order to combat this, the Church consequently adopted the revenge of the cradle policy.

Province of Canada (1840–1867)

In response to the rebellions, Lord Durham was asked to undertake a study and prepare a report offering a solution to the British Parliament.[134] In his report, Lord Durham recommended that Canadiens be culturally assimilated, with English as their only official language. In order to do this, the British passed the Act of Union of 1840, which merged Upper Canada and Lower Canada into a single colony: the Province of Canada. Lower Canada became the francophone and densely populated Canada East, and Upper Canada became the anglophone and sparsely populated Canada West. This union, unsurprisingly, was the main source of political instability until 1867.[135] The differences between the two cultural groups of the Province of Canada made it impossible to govern without forming coalition governments. Furthermore, despite their population gap, both Canada East and Canada West obtained an identical number of seats in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, which created representation problems. In the beginning, Canada East was under-represented because of its superior population size. Over time, however, massive immigration from the British Isles to Canada West occurred, which increased its population. Since the two regions continued to have equal representation in the Parliament, this meant that it was now Canada West that was under-represented. The representation issues were frequently called into question by debates on "Representation by Population", or "Rep by Pop". When Canada West was under-represented, the issue became a rallying cry for the Canada West Reformers and Clear Grits, led by George Brown.[136]

In 1844, the capital of the Province of Canada was moved from Kingston to Montreal.[137]

In this period, the Loyalists and immigrants from the British Isles decided to no longer refer to themselves as English or British, and instead appropriated the term "Canadian", referring to Canada, their place of residence. The “Old Canadians” responded to this appropriation of identity by henceforth identifying with their ethnic community, under the name "French Canadian". As such, the terms French Canadian and English Canadian were born. French Canadian writers began to reflect on the survival of their own. François-Xavier Garneau wrote an influential national epic, and wrote to Lord Elgin: “I have undertaken this work with the aim of re-establishing the truth so often disfigured, and of repelling the attacks and insults which my compatriots have been and still are the daily target of, from men who would like to oppress and exploit them all at every opportunity. I thought the best way to achieve this was to simply expose their story”.[138] His and other written works allowed French Canadians to preserve their collective consciousness and to protect themselves from assimilation, much like works like Evangeline had done for Acadians.[139][140]

Political unrest came to a head in 1849, when English Canadian rioters set fire to the Parliament Building in Montreal following the enactment of the Rebellion Losses Bill, a law that compensated French Canadians whose properties were destroyed during the rebellions of 1837-1838.[141] This bill, resulting from the Baldwin-La Fontaine coalition and Lord Elgin's advice, was a very important one as it established the notion of responsible government.[142] In 1854, the seigneurial system was abolished, the Grand Trunk Railway was built and the Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty was implemented. In 1866, the Civil Code of Lower Canada was adopted.[143][144][145] Then, the long period of political impasse that was the Province of Canada came to a close as the Macdonald-Cartier coalition began to reform the political system.[146]

Canadian province (1867–present)

On July 1, 1867, negotiations took place for a confederation between the colonies of the Province of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. This led to the British North America Act, which created the Dominion of Canada and its four founding provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Ontario. These last two came from the splitting of the Province of Canada, and used the old borders of Lower Canada for Quebec, and Upper Canada for Ontario.[147] Since this federal system's constitution was founded on the same principles as that of the United Kingdom's, each of the new provinces was guaranteed sovereign authority in the sphere of its legislative powers.[148]

After having fought as a Patriote at the Battle of Saint-Denis in 1837, George-Étienne Cartier joined the ranks of the Fathers of Confederation and submited the 72 resolutions of the Quebec Conference of 1864[149] approved for the establishment of a federated state -Quebec- whose territory was to be limited to the region which corresponded to the historic heart of the French Canadian nation and where French Canadians would most likely retain majority status. In the future, Quebec as a political entity would act as a form of protection against cultural assimilation and would serve as a vehicle for the national affirmation of the French-Canadian collective to the face of a Canadian state that would, over time, become dominated by Anglo-American culture. Despite this, the objectives of the new federal political regime were going to serve as great obstacles to the assertion of Quebec and the political power given to the provinces would be restricted. Quebec, economically weakened, would have to face political competition from Ottawa, the capital of the strongly centralizing federal state.[150]

Ultramontanism and French Canadian nationalism (1867–1914)

In this time period, the omnipresence of the Church was at its peak. The objective of clerico-nationalists consisted of promoting the values of traditional society: family, the French language, the Catholic Church and rural life. These values were the main ones upon which the French-Canadian nation's survival was based. They continued to be shared, in particular, by Roman du terroir novels and song La Bonne Chanson.[151] Though the Church was well regarded, it did sometimes have deviants of the ecclesial order to contain. A good example are the Montreal cabarets who defied Prohibition.[152]

Also during this time period, events such as the North-West Rebellion of 1885, the Manitoba Schools Question in 1896 and Ontario's Regulation 17 in 1917, turned the promotion and defenec of the rights of French Canadians into an important concern.[153] Under the aegis of the Catholic Church and the political action of Henri Bourassa, various symbols of national pride were developed, like the Carillon Sacré-Cœur, and O Canada - a patriotic song composed for Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day. Many organizations would go on to consecrate the affirmation of the French-Canadian people, including the caisses populaires Desjardins in 1900, the in 1904, the Club de Hockey Canadien (CH) in 1909, Le Devoir in 1910, the Congrès de la langue française in 1912, in 1915, L'Action nationale in 1917, etc.

On July 15, 1867, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau became Quebec's first Premier. In 1868, he created the Ministry of Public Instruction which was quickly denounced by the clergy. As such, in 1875, Boucherville abolished the Ministry and the 1867 system was restored.[154] In 1876, Pierre-Alexis Tremblay was defeated in a federal by-election because of pressure from the Church on voters, but succeeded in getting his loss annuled with the help of a new federal law. He quickly lost the subsequent election. In 1877, the Pope sent representatives to force the Quebecois Church to minimize its interventions in the electoral process.[155] At the time, the religious (ex. nuns, priests, etc.) represented 48% of teachers in Catholic schools.

As Montreal was the financial center of Canada during this era, it was the first Canadian city to implement new innovations, like electricity,[156] streetcars[157] and radio.[158] In 1885, liberal and conservative MPs formed the Parti national out of anger with the previous government for not having interceded in the execution of Louis Riel following the North-West Rebellion. They then proposed a series of unsuccessful republican reforms that supported economic nationalism and public education.[159] Then, in 1905, Lomer Gouin's government undertook a series of similar but more modest reforms that were more successful. In 1899, Henri Bourassa vigorously opposed the British government's request for Canada to join the Second Boer War. This would sow the seeds for the future conscription protests of the world wars.[160]

In 1909, the government passed a law obligating wood and pulp to be transformed in Quebec. This helped slow the Grande Hémorragie by allowing Quebec to export its finished products to the US instead of its labour force.[161] Afterwards, in 1910, Armand Lavergne passed the Loi Lavergne, the first language legislation in Quebec. It required the use of French alongside English on tickets, documents, bills and contracts issued by transportation and public utility companies. At this point in time, companies rarely recognized the majority language of Quebec.[162] Clerico-nationalists eventually started to fall out of favour in the federal elections of 1911.

World Wars (1914–1945)

When World War I broke out, Canada was automatically involved as a Dominion. Many Canadians voluntarily enlisted to fight. However, most of them were English Canadians. Unlike English Canadians, who felt a connection to the British Empire, French Canadians felt no connection to anyone in Europe. Furthermore, Canada was not threatened by the enemy, who was an ocean away and uninterested in conquering Canada. So, French Canadians saw no reason to fight. Nevertheless, a few French Canadians did enlist in the 22nd Battalion - precursor to the Royal 22e Regiment. By late 1916, the horrific number of casualties were beginning to cause reinforcement problems. After enormous difficulty in the federal government, because virtually every French-speaking MP opposed conscription while almost all the English-speaking MPs supported it, the Military Service Act became law on August 29, 1917.[163] French Canadians protested in what is now called the Conscription Crisis of 1917. The conscription protests grew so much that they eventually led to the of 1918.[164]

Following the Balfour declaration at the Imperial Conference of 1926, the Statute of Westminster of 1931 was enacted and it confirmed the autonomy of the Dominions - including Canada and its provinces - from the United Kingdom, as well as their free associaton in the Commonwealth.[165] In the 1930s, Quebec's economy was affected by the Great Depression because it greatly reduced American demand for Québécois exports. Between 1929 and 1932 the unemployment rate increased from 7,7% to 26,4%. In an attempt to remedy this, the Québécois government enacted infrastructure projects, campaigns to colonise distant regions (mostly in Abitibi-Témiscamingue and Bas-Saint-Laurent), financial assistance to farmers, and the "secours directs" - the ancestor to Canada's present Employment Insurance welfare scheme.[166]

When World War II came around, French Canadians would still be against conscription for the same reasons as last time. When Canada declared war in September 1939, the federal government pledged not to conscript soldiers for overseas service. As the war went on, more and more English Canadians voiced support for conscription, despite firm opposition from French Canada. Following a poll on April 27, 1942 that showed 72,9% of Quebec's residents were against conscription, while 80% or more were for conscription in every single other province, the federal government passed Bill 80 for overseas service, then enacted it. Protests exploded and the Bloc Populaire emerged to fight conscription until the end of the war.[163] The stark differences between the values of French and English Canada popularized the expression the "Two Solitudes". Soldier Léo Major became a hero after he liberated the city of Zwolle from the Nazis by himself in 1945.

Grande Noirceur (1944–1959)

In the wake of the 1944 conscription crisis, Maurice Duplessis of the Union Nationale ascended to power until 1959. He focused on defending provincial autonomy, Quebec's catholic and francophone heritage, and laissez-faire liberalism instead of the emerging welfare state.[169]

However, as early as 1948, French-Canadian society began to develop new ideologies and desires. This is because many big changes in society were happening simultaneously, for example the: television, refrigerator, baby boomers, workers' conflicts, electrification of the countryside, emergence of a middle class, rural exodus, expansion of universities and bureaucracies, birth of a new intelligentsia, creation of a motorway system, renaissance of litterature and poetry, urbanization, etc... New ideas would sometimes be shared in publications like the Refus global or the Cité Libre before becoming mainstream.

The more French Canadian society was shaken by social change, the more the traditional elites - grouped around clerical circles and the figure of Duplessis - reflexively hardened their conservative and French-Canadian nationalism. Over time, the people became discontent.

Modern Quebec (1960–present)

Quiet Revolution (1960–1980)

The Quiet Revolution was a period of intense modernization, secularization and social reform where, in a collective awakening, French Canadians clearly expressed their concern and dissatisfaction with the inferior socioeconomic position French-speaking Canadians had in Canada, and with the cultural assimilation of francophone minorities in the English-majority provinces. It resulted, among many other things, in the formation of the modern Québécois identity and Québécois nation.[170][171][172]

In 1960, the Liberal Party of Quebec was brought to power with a two-seat majority, having campaigned with the slogan “C'est l'temps qu'ça change” ("Its time for things to change"). This new Jean Lesage government had the "team of thunder": René Lévesque, Paul Gérin-Lajoie, Georges-Émile Lapalme and Marie-Claire Kirkland-Casgrain. This government made many reforms in the fields of social policy, education, health and economic development. It also created the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, Labour Code, Ministry of Social Affairs, Ministry of Education, Office québécois de la langue française, Régie des rentes and Société générale de financement.

The Quiet Revolution was particularly characterized by the 1962 Liberal Party's slogan "Maîtres chez nous" ("Masters in our own house"), which, to the Anglo-American conglomerates that dominated the economy and natural resources of Quebec, announced a collective will for freedom of the French-Canadian people.[173] In 1962, the government of Quebec nationalized its electricity and dismantled the financial syndicates of Saint Jacques Street.

Confrontations between the lower clergy and the laity began. As a result, state institutions began to deliver services without the assistance of the church, and many parts of civil society began to be more secular. During the Second Vatican Council, the reform of Quebec's institutions was overseen and supported by the Holy See. In 1963, Pope John XXIII proclaimed the encyclical Pacem in Terris, establishing human rights.[174][175] In 1964, the Lumen Gentium confirmed that the laity had a particular role in the “management of ”.[176]

In 1965, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism[177] wrote a preliminary report underlining Quebec's distinct character, and promoted open federalism, a political attitude guaranteeing Quebec to a minimum amount of consideration.[178][179] To favour Quebec during its Quiet Revolution, Canada, through Lester B. Pearson, adopted a policy of open federalism.[180][181] In 1966, the Union Nationale was re-elected and continued on with major reforms.[182]

In 1967, President of France Charles de Gaulle visited Quebec, the first French head of state to do so, to attend Expo 67 in Montreal. There, he addressed a crowd of more than 100,000, making a speech and ending it with the exclamation: "Vive le Québec Libre!" ("Long live free Quebec"). This declaration had a profound effect on Quebec by bolstering the burgeoning modern Quebec sovereignty movement and resulting in a political crisis between France and Canada. Following this, various civilian groups developed and acted, sometimes to the point of confronting public authority, for example, the October Crisis of 1970.[183] The meetings of the Estates General of French Canada in November 1967 marked a tipping point where relations between francophones of America, and especially francophones of Canada, ruptured. This breakdown greatly affected Quebec society's evolution (as well as those of other francophones).[184]

In 1968, class conflicts and changes in mentalities intensified.[185] That year, Option Quebec sparked a constitutional debate on the political future of the province by pitting federalist and sovereignist doctrines against each other and talking about the cultural and social emancipation of the Quebec and French-Canadian political entities. In 1973, the liberal government of Robert Bourassa initiated the James Bay Project on La Grande River. In 1974, it enacted the Official Language Act, which made French the official language of Quebec. In 1975, it established the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms and the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. In 1976, the Summer Olympics took place in Montreal.

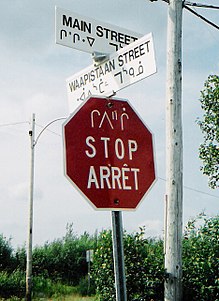

Quebec's first modern sovereignist government, led by René Lévesque, materialized when the Parti Québécois was brought to power in the 1976 Quebec general election.[186] The Charter of the French Language came into force the following year, strengthening the linguistic rights of Quebecois, most notably at work and concerning signage. Before then, Quebec was the only province to de facto practice institutional English-French bilinguilism.

Debate over sovereignty (1980–present)

Between 1966 and 1969, the Estates General of French Canada confirmed the state of Quebec to be the nation's fundamental political milieu and for it to have the right to self-determination.[187][188]

In the 1980 referendum on sovereignty-association with Canada, 60% of the votes were against. Polls showed that the overwhelming majority of anglophones and immigrants voted against, and that francophones were almost equally divided.[189] During the campaign, Pierre Trudeau stated that a "no" vote was a vote for patriation of Canada's constitution. As such, after the referendum, Lévesque went back to Ottawa to start negotiating constitutional changes. On the night of November 4, 1981, the Kitchen Accord took place. Delegations from the other nine provinces and the federal government reached a compromise in the absence of the Quebec delegation, which had left for the night to their hotels in Hull.[190] Because of this event, the National Assembly refused to recognize the new Constitution Act, 1982, which patriated the Canadian constitution and made numerous modifications to it.[191] The 1982 amendments apply to Quebec despite never having officially consented to it.[192]

Between 1982 to 1992, the Qubec government's attitude changed to prioritize reforming the federation, a behaviour described by René Lévesque as the beau risque ("beautiful risk"). The subsequent attempts at constitutional amendments by the Mulroney and Bourassa governments ended in failure with both the Meech Lake Accord of 1987 and the Charlottetown Accord of 1992, resulting in the creation of the Bloc Québécois.[193][194] After these failed attempts, Daniel Johnson of the Liberal Party of Quebec briefly gained power as the 25th premier of Quebec in 1994.[195][196] He then soon lost the following election, which established Jacques Parizeau as the new premier.[197]

In 1995, influenced by the Commission on the Political and Constitutional Future of Quebec,[198] Jacques Parizeau and his government called a referendum on Quebec's independence from Canada. This consultation ended in failure for sovereignists, though the final outcome was very close: 50.6% "no" and 49.4% "yes". On average, francophones voted 60% "yes", while anglophones and immigrants voted 95% "no".[199][200] The Unity Rally, a controversial event payed for by sponsors outside Quebec, supporting the "no" side, took place on the eve of the referendum.[201]

In 1998, following the Supreme Court of Canada's decision on the reference relating to the secession of Quebec, the Parliaments of Canada and Quebec defined the legal frameworks within which their respective governments would act in another referendum. On October 30, 2003, the National Assembly voted unanimously to affirm "that the people of Québec form a nation".[202] In 2004, accusations were made of illegal expenditures by Option Canada to aid the "no" side in 1995. Also in 2004, the sponsorship scandal began, which concerned corrupt operation of a federal program to promote federalism in Quebec. On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons passed a symbolic motion declaring "that this House recognize that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada."[203] In March 2007, the Parti Québécois was pushed back to official opposition in the National Assembly, with the Liberal party leading.

During the 2011 Canadian federal elections, Quebec voters rejected the sovereignist Bloc Québécois in favour of the federalist and previously minor New Democratic Party (NDP). As the NDP's logo is orange, this event was called the "orange wave".[204] After three subsequent Liberal governments, the Parti Québécois regained power in 2012 and its leader, Pauline Marois, became the first female premier of Quebec.[205] The Liberal Party of Quebec then returned to power in April 2014.[206] In 2018, the Coalition Avenir Québec, a then-seven-year-old political party led by François Legault, won the provincial general elections, obtaining a majority of seats in the National Assembly. Between 2020 and 2021, Quebec took measures to protect itself against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Government and politics

The head of government in Quebec is the premier (called premier ministre in French), who leads the largest party in the unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale) from which the Executive Council of Quebec is appointed. The lieutenant governor represents the Queen of Canada and acts as the province's head of state.[law 1][207] Until 1968, the Quebec legislature was bicameral,[208] consisting of the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly. In that year, the Legislative Council was abolished and the Legislative Assembly was renamed the National Assembly. Quebec was the last province to abolish its legislative council.

The Government of Quebec awards an order of merit called the National Order of Quebec. Inspired in part by the French Legion of Honour, it is conferred upon men and women born or living in Quebec (but non-Quebecers can be inducted as well) for outstanding achievements.[209]

Governmental organization

Canadian Monarchy

Quebec is founded on the Westminster system, and is both a liberal democracy and a constitutional monarchy with parliamentary regime.[210] Quebec is a member state of the Canadian federation, as such, its leader is Elizabeth II, who is the incarnation of the Crown of Canada and holder of the government and executive power in the province of Quebec.

Provincial Parliament

The Parliament of Quebec is the legislative body of Quebec. It is made up of the lieutenant governor (representative of the Crown) and an elective chamber bearing the name of the National Assembly (representative of the people). Each legislature has a maximum duration of five years, however, barring exceptions, Quebec now conducts fixed-date elections in October every four years.[211]

Premier and the Executive Council

The Executive Council (or Council of Ministers), chaired by the premier, is the primary body for executive power in Quebec.[212] Its members are the principal advisers to the lieutenant governor in the exercise of executive power.

Lieutenant governor

The lieutenant governor is the Queen's representative within the State of Quebec. He or she has specific and symbolic powers.[law 2][207]

Federal representation

Quebec has 78 members of Parliament (MPs) in the House of Commons of Canada.[213] They are elected in federal elections. At the level of the Senate of Canada, Quebec is represented by 24 senators, which are appointed on the advice of the prime minister of Canada.[214]

Public administration

The Quebec State is the depositary of administrative and police authority in the areas of exclusive jurisdiction it holds concerning laws and constitutional convention.