The Outlaw

| The Outlaw | |

|---|---|

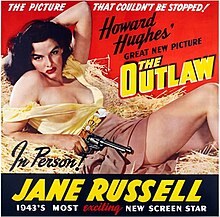

Theatrical Poster | |

| Directed by | Howard Hughes |

| Written by | Jules Furthman |

| Produced by | Howard Hughes |

| Starring | Jack Buetel Jane Russell Walter Huston Thomas Mitchell |

| Cinematography | Gregg Toland |

| Edited by | Wallace Grissell |

| Music by | Victor Young |

Production company | Howard Hughes Productions |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3,400,000[1] |

| Box office | $5,075,000 (est. US/Canada rentals)[2] |

The Outlaw is a 1943 American Western film, directed by Howard Hughes and starring Jack Buetel, Jane Russell, Thomas Mitchell, and Walter Huston. Hughes also produced the film, while Howard Hawks served as an uncredited co-director. The film is notable as Russell's breakthrough role, and she became regarded as a sex symbol and a Hollywood icon. Later advertising billed Russell as the sole star.

Plot[]

Sheriff Pat Garrett welcomes his old friend Doc Holliday to Lincoln, New Mexico. Doc is looking for his stolen horse and finds it held by Billy the Kid. Despite this, the two gunfighters take a liking to each other, much to Garrett's disgust. Doc still tries to steal his horse back late that night, but Billy is waiting for him outside the barn.

After that, Billy decides to sleep in the barn, and shots are fired at him. He overpowers his ambusher, who turns out to be Rio McDonald, Doc's love-interest. She is out to avenge her dead brother. It is implied that the Kid rapes Rio after ripping off her dress.[3]

The next day, a stranger offers to shoot Garrett in the back while the Kid distracts the lawman. But, he is only setting the Kid up. Billy, suspicious as always, guns the stranger down just before being shot himself. There are no witnesses, and Garrett tries to arrest Billy. Garrett does not understand when Doc sides with the Kid. As the pair start to leave, Garrett shoots Billy. Doc in response shoots the gun out of his hand and also shoots and kills two of Garrett's men.

Doc flees with Billy to the home of Rio and her aunt, Guadalupe. With a posse after them, Doc rides away. Instead of killing the unconscious Kid, Rio instead nurses him to health over the next month. By the time Doc returns, Rio has fallen in love with her patient. Doc is furious that Billy has stolen his girlfriend. After Doc's anger subsides a bit, the Kid gives him a choice: the horse or Rio. To Billy's annoyance, Doc picks the horse. Angered that both men value the animal more than her, Rio fills their canteens with sand. The two ride off without noticing.

On the trail, they are pursued by Garrett and a posse. The pair surmise that Rio tipped the sheriff off. Doc kills a few men from long range, but leaves Garrett unharmed.

When Doc wakes one morning, he finds Billy gone and Garrett waiting to handcuff him and take him back to town. Stopping at Rio's, the two men find that Billy has left Rio tied up in sight of water in revenge. Suspecting that Billy loves Rio (even if he doesn't realize it) and will return to free her, Garrett waits. When the Kid returns, he is captured.

On the way back to town, they are surrounded by hostile Mescaleros. Garrett reluctantly frees his prisoners and returns their revolvers, after extracting a promise from Doc that he will give them back and make Billy do the same. They manage to elude the Indians, but Doc refuses to honor his word.

As Doc tries to leave with his horse, Billy stops him. The two men decide to have a duel, which Garrett expects Billy to lose. However, as they await the signal (the end of a clock signalling eight o'clock), Billy realizes that Doc is a true friend, and moves his hands away from his guns. Doc tries to provoke him, inflicting minor wounds in one hand and both ears, but the Kid still will not fire. The two reconcile. Furious, Garrett calls Doc out, despite not having a chance. Doc makes no attempt to shoot his friend and is fatally wounded. Garrett is aghast.

After Doc is buried, Garrett offers to give Billy their friend's revolvers. He also persuades Billy to give him his guns, saying that he can claim that it is Billy in the grave. The Kid can leave his past behind him and have a fresh start in life. But, it is a trick. Garrett had removed the firing pins from Doc's revolvers. While comparing the guns, he inadvertently switched one of Doc's for his, so neither of the men's guns fires. Billy pulls out a second, working gun. He handcuffs Garrett, judging that the lawman will say that Billy is dead rather than admit the Kid left him helpless. As he is riding away, Billy stops and looks back; Rio joins him on his horse.

Cast[]

- Jack Buetel as Billy the Kid

- Jane Russell as Rio McDonald

- Thomas Mitchell as Pat Garrett

- Walter Huston as Doc Holliday

- Mimi Aguglia as Guadalupe

- Joe Sawyer as Charley

- Gene Rizzi as stranger who tries to trick Billy

- Dickie Jones as boy (uncredited)

- Edward Peil Sr. as Swanson (uncredited)

- Lee Shumway as card dealer (uncredited)

Production[]

In 1941, while filming The Outlaw, Hughes felt that the camera did not do justice to Jane Russell's bust. He employed his engineering skills to design a new cantilevered underwire bra to emphasize her figure. Hughes added curved structural steel rods that were sewn into the brassiere under each breast cup and connected to the bra's shoulder straps. This arrangement allowed the breasts to be pushed upward and the bra shoulder straps to be moved away from the neck, exposing more of her bosom. Contrary to many media reports afterward, Russell did not wear the bra during filming; she said in her 1988 autobiography that the bra was so uncomfortable that she secretly discarded it.[4][5] She wrote that the "ridiculous" contraption hurt so much that she wore it for only a few minutes, and instead wore her own bra. To prevent Hughes from noticing, Russell padded the cups with tissue and tightened the shoulder straps before returning to the set. She later said "I never wore it in The Outlaw, and he never knew. He wasn’t going to take my clothes off to check if I had it on. I just told him I did."[6] The famed bra ended up in a Hollywood museum—a false witness to the push-up myth.[7]

Although the film was completed in February 1941, Hughes had trouble getting it approved by the Hollywood Production Code Administration due to its emphasis on and display of Russell's breasts. The Production Administration set the standards for morally acceptable content in motion pictures, and ordered cuts to the film. Hughes reluctantly removed about 40 feet, or a half-minute, of footage that prominently featured Russell's bosom. However, 20th Century Fox decided to cancel its agreement to release The Outlaw; as a result, Hughes stood to lose millions of dollars. Ever the resourceful businessman, he schemed to create a public outcry for his film to be banned.

Hughes had his managers call ministers, women's clubs and housewives, informing them about the 'lewd picture' he was about to release. The public responded by protesting and trying to have the film banned, which generated the publicity Hughes needed to establish a demand for the film and get it released. The resulting controversy created enough interest to get The Outlaw into theaters for one week in 1943, and then it was pulled due to violations of the Production Code. The film was released widely on April 23, 1946, when RKO Radio Pictures premiered the film in San Francisco, where it became a box-office hit. By the end of 1946, the film had earned $3 million in domestic rentals.[8] Additional re-releases in 1950 and 1952[8] brought its lifetime rental earnings to $5.075 million.[2]

Hughes sued Classic Film Museum, Inc. and Alan J. Taylor for unlawful distribution of Hell's Angels, Scarface, and The Outlaw. When it emerged that The Outlaw had fallen into the public domain in 1969 for lack of copyright renewal, the case was settled, with Classic Film Museum agreeing to stop distribution of the two copyrighted titles, and Hughes withdrawing his claim on The Outlaw.[9][10]

The film was later colorized twice. The first colorization was released by Hal Roach Studios in 1988. The second colorized version, produced by Legend Films, was released to DVD on June 16, 2009, featuring both the newly colorized edition and a restored black-and-white edition of the film. The DVD version also featured an audio commentary by Jane Russell and actress Terry Moore, Hughes's alleged wife. Russell approved of the colorization, stating "The color looked great. It was not too strong, like in many of the early colorized movies that made the films look cheap."[citation needed]

Author Robert Lang writes that the true expression of sexuality in this film is based in the relationship between Doc Holliday and Billy the Kid. He says that the film is about "the complications that arise when Doc Holliday falls in love with Billy the Kid, and Pat Garett becomes jealous of the bond that develops between the two men."[11] Hughes scholars and historians scoff at this highly subjective Hollywood interpretation; they suggest that Hughes would have never allowed any form of sexuality to be expressed in his films that might take away from the effect and value of his starlet, Jane Russell.[12]

Notes[]

- ^ Dietrich, Noah; Thomas, Bob (1972). Howard, The Amazing Mr. Hughes. Greenwich, Connecticut: Fawcett Publications, Inc. p. 153. ISBN 978-0449136522.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "All Time Domestic Champs". Variety. January 6, 1960. p. 34.

- ^ 20/20 Movie Review of The Outlaw (1943)

- ^ "Jane Russell". The Economist. March 12, 2011. p. 101.

- ^ "Jane Russell". March 1, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

A joke at that time was that 'Culture is the ability to describe Jane Russell without moving your hands.'

- ^ Tiffin, George (September 30, 2015). A Star is Born: The Moment an Actress becomes an Icon. Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1-78185-936-0.

He wasn’t going to take my clothes off to check if I had it on. I just told him I did."

- ^ Jessica Seigel (February 13, 2004). "The Cups Runneth Over". New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Edgarton, Gary R. (2012). Westerns: The Essential 'Journal of Popular Film and Television' Collection. ISBN 978-0-415-78323-1.

Some court decisions were won, others were lost, but at the end of its run, The Outlaw had managed to play 5,000 of a possible 18,000 dates and, even though some of the biggest houses had to be by-passed, it still managed to gross $3,000,000, which, by this time, was little more than Hughes' costs. Over the next few years most of this opposition evaporated – even the Legion of Decency lifted its condemnation. During 1950 and 1952, the film went through two more general releases and raised its total rental gross to over five million, making it second only to Duel in the Sun, a calculated imitation done in color, as the second biggest box office Western up to this point.

- ^ Court case: Agreement, Summa Corporation v. Classic Film Museum, Inc., Civil Action No. 75-81 N.D. United Artists Howard Hughes Files collection, Archives Division, Texas State Library.

- ^ Pierce, David (June 2007). "Forgotten Faces: Why Some of Our Cinema Heritage Is Part of the Public Domain". Film History: An International Journal. 19 (2): 125–43. doi:10.2979/FIL.2007.19.2.125. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 25165419. OCLC 15122313. S2CID 191633078.. See note #17.

- ^ Lang, Robert (2002). Masculine Interests: Homoerotics in Hollywood Films. New York City: Columbia University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-231-11300-7.

- ^ Gerber, A. B. (1968). Bashful Billionaire: The Story of Howard Hughes. New York: Dell Pub. Co.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Outlaw (film). |

- The Outlaw at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Outlaw at the TCM Movie Database

- The Outlaw at AllMovie

- The Outlaw is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The Outlaw at IMDb

- Advertising Blimp "Kept off the screen for 3 years, it's coming at last! The Outlaw starring Jane Russell"

- 1943 films

- English-language films

- 1943 Western (genre) films

- American films

- American Western (genre) films

- Biographical films about Billy the Kid

- Films set in New Mexico

- RKO Pictures films

- Films directed by Howard Hawks

- Films directed by Howard Hughes

- Films with screenplays by Jules Furthman

- Films scored by Victor Young

- American black-and-white films

- Cultural depictions of Doc Holliday

- Cultural depictions of Pat Garrett

- Obscenity controversies in film