The Pennsylvania Gazette

Statue of Benjamin Franklin holding a copy of The Pennsylvania Gazette | |

| Founder(s) | Samuel Keimer Benjamin Franklin in 1729, who bought and reoriented the publication into a 'news only' newspaper |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1728 (as The Universal Instructor in all Arts and Sciences: and Pennsylvania Gazette) |

| Political alignment | Non partisan |

| Ceased publication | 1800 |

| Headquarters | Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| City | Philadelphia |

The Pennsylvania Gazette was one of the United States' most prominent newspapers from 1728 until 1800. In the several years leading up to the American Revolution the paper served as a voice for colonial opposition to British colonial rule, especially as it related to the Stamp Act, and the Townshend Acts.

History[]

The newspaper was first published in 1728 by Samuel Keimer and was the second newspaper to be published in Pennsylvania under the name The Universal Instructor in all Arts and Sciences: and Pennsylvania Gazette, alluding to Keimer's intention to print out a page of Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences in each copy.[1]

On October 2, 1729, Samuel Keimer, the owner of the Gazette, fell into debt and before fleeing to Barbados sold the newspaper to Benjamin Franklin and his partner Hugh Meredith,[2][3][4][5] and shortened its name, as well as dropping Keimer's grandiose plan to print out the Cyclopaedia.[1] Franklin not only printed the paper but also often contributed pieces to the paper under aliases. His newspaper soon became the most successful in the colonies.[3]

On December 28, 1732, Franklin announced in Gazette that he had just printed and published the first edition of The Poor Richard, (better known as Poor Richard's Alamanack) by Richard Saunders, Philomath.[6] On August 6, 1741 Franklin published an editorial about deceased Andrew Hamilton, a lawyer and public figure in Philadelphia who had been a friend. The editorial praised the man highly and showed Franklin had held the man in high esteem.[7]

On October 19, 1752,[8] Franklin published a third-person account of his pioneering kite experiment in The Pennsylvania Gazette, without mentioning that he himself had performed it.[9]

Primarily a publication for classified ads, merchants and individuals listed notices of employment, lost and found goods and items for sale; the newspaper also reprinted foreign news. Most entries involved stories of travel.[10] The gazette also published advertisements for runaway slaves and indentured servants.[11]

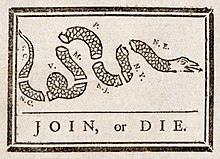

This newspaper, among other firsts, would print the first political cartoon in America, Join, or Die, authored by Franklin himself.[12]

The paper ceased publication in 1800, ten years after Franklin's death.[13] It is claimed that the publication later reemerged as the Saturday Evening Post in 1821.[14]

There are three known copies of the original issue, which are held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Wisconsin State Historical Society.[1]

Today, The Pennsylvania Gazette moniker is used by an unrelated bi-monthly alumni magazine of the University of Pennsylvania, which Franklin founded and served as a trustee.

Archives are available online for a fee.[15]

See also[]

- Early American publishers and printers

- Pennsylvania Chronicle

- The Constitutional Post

- Join, or Die

- Liberty's Kids

- The Drinker's Dictionary

References[]

- ^ a b c "Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia". Library of Congress. 2006. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ Isaacson, 2003, p. 64

- ^ a b Benjamin Franklin Historical Society, Essay

- ^ Aldridge, 1962, p. 77

- ^ Clark & Wetherall, 1989, p. 282

- ^ Miller, 1961, p. 97

- ^ Konkle, Burton Alva (1932). Benjamin Chew 1722–1810: Head of the Pennsylvania Judiciary System Under Colony and Commonwealth. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 17–29 (28–29).

- ^ Tom Tucker, Bolt Of Fate: Benjamin Franklin And His Fabulous Kite (PublicAffairs, 2009) p135

- ^ Steven Johnson (2008) The Invention of Air, p. 39 ISBN 978-1-59448-401-8

- ^ Zach Hutchins, "Travel Writing, Travel Reading, and the Boundaries of Genre: Embracing the Banal in Franklin's 1747 Pennsylvania Gazette," Studies in Travel Writing 17.3 (2013):300-19.

- ^ Smith, Billy G., and Richard Wojtowicz. Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisements for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728-1790. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv4s7gw2. Accessed 3 Sept. 2021.

- ^ "Today in History: January 17". Library of Congress. 2006. Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- ^ "The Pennsylvania Gazette". Accessible Archives. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ About the Saturday Evening Post Archived February 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Sources[]

- Aldridge, Alfred Owen (February 15, 1962). "Benjamin Franklin and the "Pennsylvania Gazette"". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. 106 (1): 77–81. JSTOR 985213.

- Clark, Charles E.; Wetherell, Charles (April 1989). "The Measure of Maturity: The Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728-1765". The William and Mary Quarterly. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 46 (2): 279–303. JSTOR 1920255.

- Bernard Bailyn; John B. Hench, eds. (1981) [1980]. The Press & the American Revolution. Boston : Northeastern University Press (Originally published: Worcester, Mass. : American Antiquarian Society). ISBN 978-0-9303-50307.

- Miller, C. William (1961). "Franklin's "Poor Richard Almanacs": Their Printing and Publication". Studies in Bibliography. Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia. 14: 97–115. JSTOR 40371300.

External links[]

Media related to The Pennsylvania Gazette at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Pennsylvania Gazette at Wikimedia Commons

- Defunct newspapers of Philadelphia

- Publications established in 1728

- Publications disestablished in 1800

- 1728 establishments in Pennsylvania

- Newspapers of colonial America