The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine

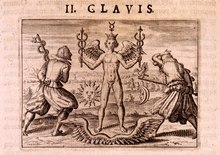

The second key. Woodcut from 1618. | |

| Author | Basil Valentine |

|---|---|

| Original title | Ein kurtz summarischer Tractat, von dem grossen Stein der Uralten |

| Translator | Michael Maier |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Alchemy |

| Publisher | Johann Thölde |

Publication date | 1599 |

The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine is a widely reproduced alchemical book attributed to Basil Valentine. It was first published in 1599 by Johann Thölde who is likely the book's true author.[1] It's presented as a sequence of alchemical operations encoded allegorically in words, to which images have been added. The first Basil Valentine book to discuss the keys is Ein kurtz summarischer Tractat, von dem grossen Stein der Uralten ("A Short Summary Tract: Of the great stone of the ancients"), 1599.

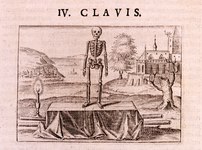

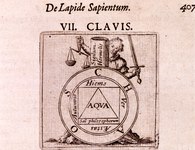

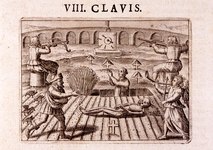

The first part of the book is a discussion of general alchemical principles and advice about the philosopher's stone. The second half of Ein kurtz summarischer Tractat, under the subtitle "The Twelve Keys", contains twelve short chapters. Each chapter, or "key", is an allegorical description of one step in the process by which the philosopher's stone may be created. With each step, the symbolic names (Deckname, or code name) used to indicate the critical ingredients are changed, just as the ingredients themselves are transformed. The keys are written in such a fashion as to conceal as well as to illuminate: only a knowledgeable reader or alchemical adept was expected to correctly interpret the veiled language of the allegorical text and its related images.[2]

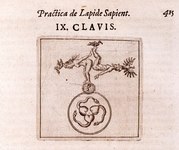

Illustrations[]

The 1599 edition does not include illustrations. Woodcuts appear in the 1602 edition. Revised engravings for all twelve steps appear in Tripus Aureus ("Golden Tripod"). This 1618 Latin translation by Michael Maier includes three works, the first of which is Basil Valentine's.[2]: 153 [3] Since the texts predate the images, the texts should be considered primary.[2]: 144

- The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine, as engraved by Matthaeus Merian (1593–1650), and published in the collection Musaeum hermeticum, Francofurti : Apud Hermannum à Sande, 1678

First key.

Second key

Third key

Fourth key

Fifth key

Sixth key

Seventh key

Eighth key

Ninth key

Tenth key

Eleventh key

Twelfth key

Physicochemical interpretation[]

The allegorical text and fantastic visual imagery of alchemical writings make them difficult to interpret. A physicochemical reading was proposed in the twenty-first century. Chemist and historian Lawrence M. Principe has drawn on knowledge of chrysopoetic symbolism and experimentally tested possible chemical processes and practices which may correspond to several of Basil Valentine's twelve steps. Visually he refers to the 1602 woodcuts.[2]: 144 Principe speculates that the twelve keys may involve descriptions of varying types. Some of the early keys may encode descriptions of actual laboratory techniques and observed results. Other keys may be theoretical extrapolations of what could be accomplished: ideas for experiments that had not yet been successfully carried out. The final keys may be descriptions of methods based on other writers' textual precedents.[2]: 157–8

There is evidence that the "father of chemistry", Robert Boyle, also volatilized gold by following the steps in Basil Valentine's keys.[4][5] Sir Isaac Newton also seriously studied the writings attributed to 'Basil Valentine'.[6]

See also[]

External links[]

References[]

- ^ John Maxson Stillman. "Basil Valentine. A Seventeenth Century Hoax." The Popular Science Monthly, 1912.

- ^ a b c d e Principe, Lawrence M. (2013). The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226923789.: 152–153

- ^ McLean, Adam. "12 Keys of Basil Valentine". Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Keiger, Dale (February 1999). "All that glitters". Johns Hopkins Magazine. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ Principe, Lawrence M. (1998). The aspiring adept : Robert Boyle and his alchemical quest : including Boyle' s "lost" Dialogue on the Transmutation of Metals. Princeton: Princeton university press. ISBN 0691050821.

- ^ Brewster, David (1855). Memoirs of the life, writings, and discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton. Edinburgh: T. Constable and Co.

- Alchemical documents

- Emblem books

- 1599 books

- 1599 in science