Pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber (or "Latin Pseudo-Geber") refers to a corpus of Latin alchemical writing dated to the late 13th and early 14th centuries, attributed to Geber (Jābir ibn Hayyān), an early alchemist of the Islamic Golden Age. The most important work of the corpus is Summa perfectionis magisterii ("The Height of the Perfection of Mastery"), likely written slightly before 1310, whose actual author has sometimes been identified as Paul of Taranto.[1] The work was influential in the domain of alchemy and metallurgy in late medieval Europe.

The historicity of Jābir ibn Hayyān itself is in question, and most of the numerous Islamic works attributed to him are, themselves, pseudepigraphic. It is common practice of historians of alchemy to refer to the earlier body of Islamic alchemy texts as the Corpus Jabirianum or Jabirian Corpus, and to the later, 13th to 14th century Latin corpus as Pseudo-Geber or Latin Pseudo-Geber, a term introduced by Marcellin Berthelot. The "Pseudo-Geber problem" is the question of a possible relation between the two corpora. This question has long been controversially discussed. It is now mostly thought that at least parts of Latin Pseudo-Geber are based on earlier Islamic authors such as Al-Razi.

Corpus[]

The following set of books is called the "Pseudo-Geber Corpus" (or the "Latin Geber Corpus"). The works were first edited in the 16th century,[2] but had been in circulation in manuscript form for roughly 200 years beforehand. The stated author is Geber or Geber Arabs (Geber the Arab), and it is stated in some copies that the translator is Rodogerus Hispalensis (Roger of Hispania). The works attributed to Geber include:

- Summa perfectionis magisterii ("The Height of the Perfection of Mastery").

- Liber fornacum ("Book of Furnaces"),

- De investigatione perfectionis ("On the Investigation of Perfection"), and

- De inventione veritatis ("On the Discovery of Truth").

Being the clearest expression of alchemical theory and laboratory directions available until then—in a field where mysticism, secrecy, and obscurity were the usual rule—Pseudo-Geber's books were widely read and influential among European alchemists.[3]

The Summa Perfectionis in particular was one of the most widely read alchemy books in western Europe in the late medieval period.[4] Its author assumed that all metals are composed of unified sulfur and mercury corpuscles[5] and gave detailed descriptions of metallic properties in those terms. The use of an elixir for transmuting base metals into gold is explained (see philosopher's stone) and a lengthy defense is given defending alchemy against the charge that transmutation of metals was impossible.

The practical directions for laboratory procedures were so clear that it is obvious the author was familiar with many chemical operations. It contains early recipes for producing mineral acids,[6] much like the earlier Arabic corpus.[7] It was not equaled in chemistry until the 16th century writings of chemist Vannoccio Biringuccio, mineralogist Georgius Agricola and assayer Lazarus Ercker.[8]

The next three books on the list above are shorter and are, to a substantial degree, condensations of the material in the Summa Perfectionis.

Two further works, Testamentum Geberi and Alchemia Geberi, are "absolutely spurious, being of a later date [than the other four]", as Marcellin Berthelot put it,[9] and they are usually not included as part of the Pseudo-Geber corpus. Their author is not the same as the others, but it is not certain that the first four have the same author either.[10] De Inventione Veritatis has the earliest known recipe for the preparation of nitric acid.[6]

Manuscripts:

- Geber Liber Fornacum translatum [...] per Rodericum Yspanensem, Biblioteca Marciana, Venice, MS. Latin VI.215 [3519].

- Geberi Arabis Philosophi sollertissimi rerum naturalium pertissimi, liber fornacum ad exterienda [...] pertimentum interprete Rodogero Hisaplensi interprete, Glasgow University Library, Ferguson MS. 232.

- Eejisdem 'liber fornacum', ad exercendam chemiam pertinentium, interprete Rodogero Hispalensi, British Library, MS Slane 1068

Early editions:

- 1525: Faustus Sabaeus, Geberis philosophi perspicacissimi Summa perfectionis magisterii in sua natura ex exemplari undecumque emendatissimi nuper edita, Marcellus Silber, Rome.

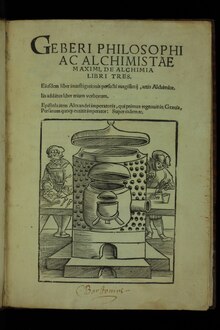

- 1528, 1529: Geberi philosophi de Alchimia libri tres, Strasbourg

- 1531: Johann Grüninger, Geberi philosophi ac alchimistae maximi de alchimia libri tres, Strasbourg.

- 1541: Peter Schoeffer, Geberis philosophi perspicacissimi, summa perfectionis magisterii in sua natur ex bibliothecae Vaticanae exemplari (hathitrust.org)

- 1545: Alchemiae Gebri Arabis libri, Nuremberg

- 1572: Artis Chemicae Principes, Avicenna atque Geber, Basel

- 1598: Geberi Arabis de alchimia traditio, Strasbourg.

- 1668: Georgius Hornius, Gebri Arabis Chemia sive traditio summae perfectionis et investigation magisterii, Leiden

- 1682: Gebri, regis Arabum, summa perfectionis magisterii, cum libri invastigationis magisterii et testamenti ejusdem Gebri - et Avicennae minearlium additione, Gdansk

Early translations:

- 1530 Das Buch Geberi von der Verborgenheyt der Alchymia, Strasbourg

- 1551: Giovanni Bracesco, Esposizione di Geber filosofo, Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari e fratelli, Venice

- 1692: William Salmon, Gebri Arabis Summa: The Sum of Geber Arabs

- 1710: Geberi curieuse vollständige Chymische Schriften, Frankfurt

Authorship[]

Islamic alchemy was held in high esteem by 13th century European alchemists, and the author adopted the name of an illustrious predecessor, as was usual practice at the time. The authorship of Geber (Jabir ibn Hayyam) was first questioned in the late 19th century by the studies of Kopp,[11] Hoefer, Berthelot, and Lippmann. The corpus is clearly influenced by medieval Islamic writers (especially by Al-Razi, and to a lesser extent, the eponymous Jabir). The identity of the author remains uncertain. He may have lived in Italy or Spain, or both. Some books in the Geber corpus may have been written by authors that post-date the author of the Summa Perfectionis, as most of the other books in the corpus are largely recapitulations of the Summa Perfectionis.[9] Crosland (1962) refers to Geber as "a Latin author" while still emphasizing the identity of the author being "still in dispute". [12] William R. Newman in his 1991 critical edition of the Summa perfectionis argues that the author of the Summa perfectionis was Paul of Taranto.[4]

The estimated date for the first four books is 1310, and they could not date from much before that because no reference to the Summa Perfectionis is found anywhere in the world before or during the 13th century. For example, there is no mention in the 13th century writings of Albertus Magnus and Roger Bacon.[13]

The degree of dependence of the corpus from actual Islamic sources is somewhat disputed: Brown (1920) asserted that the Pseudo-Geber Corpus contained "new and original facts" not known from Islamic alchemy, specifically mention of nitric acid, aqua regia, oil of vitriol and silver nitrate.[9] Already in the 1920s, Eric John Holmyard criticized the claim of Pseudo-Geber being "new and original" compared to medieval Islamic alchemy, arguing for direct derivation from Islamic authors.[14] Holmyard later argued that the then-recent discovery of Jabir's The Book of Seventy diminished the weight of the argument of there being "no Arabic originals" corresponding to Pseudo-Geber,[15] By 1957, Holmyard was willing to admit that "the general style of the works is too clear and systematic to find a close parallel in any of the known writings of the Jabirian corpus" and that they seemed to be "the product of an occidental rather than an oriental mind" while still asserting that the author must have been able to read Arabic and most likely worked in Moorish Spain.[16]

With Brown (1920), Karpenko and Norris (2001) still assert that the first documented occurrence of aqua regia is in Pseudo-Geber.[6] By contrast, Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan (2005) claimed that Islamic texts dated to before the 13th century, including the works of Jabir and Al-Razi, did in fact contain detailed descriptions of substances such as nitric acid, aqua regia, vitriol, and various nitrates,[17] and Al-Hassan in 2009 argued that the Pseudo-Gerber Corpus was a direct translation of a work originally written in Arabic, pointing to a number of Arabic Jabirian manuscripts which already contain much of the theories and practices that Berthelot previously attributed to the Latin corpus.[7]

References[]

- ^ William R. Newman. New Light on the Identity of Geber", Sudhoffs Archiv 69 (1985): 79-90

- ^ Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry, Allen G. Debus, Jeremy Mills Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-0-9546484-1-1.

- ^ Holmyard, E. J.; Jabir; Russell, Richard (September 1997). The Works of Geber. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-0015-2. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Summa perfectionis of Pseudo-Geber: A critical edition, translation, and study, by William R. Newman (1991)

- ^ "The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science". John A Norris. Ambix vol. 53 no. 1, March 2006, pp. 43-56.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Vladimir Karpenko and John A. Norris (2001), Vitriol in the history of Chemistry.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, Critical-Issues Studies in al-Kimya′: Critical Issues in Latin and Arabic Alchemy and Chemistry, published as book by Olms in 2009 and as article by Centaurus journal in 2011. Online versions are available at Geber Problem @ History of Science and Technology in Islam and at Scribd.

- ^ See German article de:Lazarus Ercker.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chapter VI: "The Pseudo-Geber" in A History of Chemistry from the Earliest Times (2nd ed., 1920), by J.C. Brown.

- ^ Long, Pamela O. (2001). Openness, secrecy, authorship: technical arts and the culture of knowledge from antiquity to the Renaissance. JHU Press. pp. 146 147. ISBN 978-0-8018-6606-7. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ Hermann Kopp, Beitraege zur Geschichte der Chemie Drittes Stueck (Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1875), 28-33n.

- ^ P. Crosland, Maurice, Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry, Harvard University Press, 1962; republished by Dover Publications, 2004 ISBN 0-486-43802-3, ISBN 978-0-486-43802-3, p. 15 and p. 36.

- ^ History of Analytical Chemistry, by Ferenc Szabadváry (1960).

- ^ "[Berthelot] deliberately wanted to underrate Jābir […], the choice of Jābir’s works made by Berthelot is entirely misleading." "It is here that Berthelot’s ignorance of Arabic led him astray. As a matter of fact, the Summa is full of Arabic phrases and turns of speech, and so are the other Latin works", cited after Hassan (2005)

- ^ Makers of Chemistry, by Eric John Holmyard (1931).

- ^ Eric John Holmyard, Alchemy, 1957, page 134: "The question at once arises whether the Latin works are genuine translations from the Arabic, or written by a Latin author and, according to common practice, ascribed to Jabir in order to heighten their authority. That they are based on Muslim alchemical theory and practice is not questioned, but the same may be said of most Latin treatises on alchemy of that period; and from various turns of phrase it seems likely that their author could read Arabic. But the general style of the works is too clear and systematic to find a close parallel in any of the known writings of the Jabirian corpus, and we look in vain in them for any references to the characteristically Jabirian ideas of "balance" and the alphabetic numerology. Indeed for their age they have a remarkably matter of fact air about them, theory being stated with a minimum of prolixity and much precise practical detail being given. The general impression they convey is that they are the product of an occidental rather than an oriental mind, and a likely guess would be that they were written by a European scholar, possibly in Moorish Spain. Whatever their origin, they became the principal authorities in early Western alchemy and held that position for two or three centuries."

- ^ Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan, Cultural contacts in building a universal civilisation: Islamic contributions, published by O.I.C. Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture in 2005 and available online at History of Science and Technology in Islam

- 13th-century alchemists

- 14th-century alchemists

- Pseudepigraphy

- 13th-century scientists