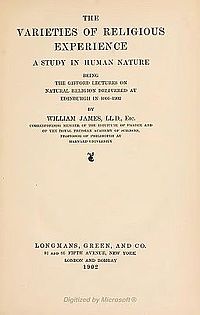

The Varieties of Religious Experience

| |

| Author | William James |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature, Being the Gifford Lectures on Natural Religion Delivered at Edinburgh in 1901–1902[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subjects | Philosophy of religion Psychology of religion |

| Publisher | Longmans, Green & Co. |

Publication date | 1902 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 534 |

| LC Class | BR110.J3 1902a |

| Followed by | Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking (1907) |

The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature is a book by Harvard University psychologist and philosopher William James. It comprises his edited Gifford Lectures on natural theology, which were delivered at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland between 1901 and 1902. The lectures concerned the psychological study of individual private religious experiences and mysticism, and used a range of examples to identify commonalities in religious experiences across traditions.

Soon after its publication, Varieties entered the Western canon of psychology and philosophy and has remained in print for over a century.

James later developed his philosophy of pragmatism. There are many overlapping ideas in Varieties and his 1907 book Pragmatism.[2]

Contents[]

The book has 14 chapters covering 20 lectures and a postscript.

Lecture I. Religion and Neurology.

In this first lecture, James outlines the scope of his investigation. Neither a theologian nor a historian of religion, James states that he is a psychologist and therefore his lectures will concern the psychology of religious feelings, rather than the institutions of religion. This further limits his enquiry to religious phenomena that have been articulated and recorded by individuals, limiting his study to either modern writers or sources from history which have become classic texts. James then distinguishes between questions concerning something's origin and its value, insisting that his purpose is to understand the origin of religious experiences and not to pass judgement on their value. This means that if James finds some material or natural cause of religious experience in his study, this should not lead anyone to conclude that this undermines their religious or spiritual value.

Lecture II. Circumscription of the Topic.

In his circumscription of the topic, James outlines how he will define religion for the sake of the lectures. Religious institutions are found wanting in this regard since they are not primary but rather depend on the private religious feeling of individuals, especially those of the founders of such institutions. James thus defines the essence of religion as "the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider divine".[3] He then distinguishes religion from moral or philosophical systems such as Stoicism which also teach a particular way or living, arguing that religion is distinguished by the presence of a sentiment which gladly assents to it. Religion is thus that which combines a moral system with a particular positive sentiment.

Lecture III. The Reality of the Unseen.

James begins his third lecture by noting that all states of mind involve some kind of object but that religious experiences involve an object which cannot be sensibly perceived. This ability to be aware of insensible objects in the mind, such as being aware of a presence in the room, is an ability particular to human beings. These experiences are sometimes connected with religion but not always, and James insists that they are not at all unusual. For those who have had such experiences, they are irrefutable and no rational argument will dissuade someone of their reality, even if the subject cannot explain or answer for the experience themselves.

James criticizes the rationalistic and scientific approaches, which would question these experiences, as being rarely convincing in the sphere of religion: rational arguments about religion are compelling for someone only if they already believe the conclusion. This is just a fact of human psychology for James, not a value judgement: humans are more persuaded irrationally and emotionally than they are by reasons. James concludes his lecture by noting the different kinds of responses such experiences can elicit (joy and sorrow), the variation of which will occupy his following lectures.

Lectures IV and V. The Religion of Healthy-Mindedness.

In these lectures, James outlines what he calls healthy-minded religion. Healthy-minded religion is one branch of James's two-fold typology of religion (the other being sick souled religion, discussed in the following chapters). This kind of religion is characterised by contentment; it is a life untroubled by the existence of evil and confident in its own salvation. For the healthy-minded individual, one's happiness and contentment is regarded as evidence for the truth of their religion. James follows Francis William Newman in calling this kind of religion 'once-born', referring to the lack of religious conversion or second birth experience. James presents a number of examples of healthy-minded religion throughout these two lectures and offers the mind-cure movement as an exemplar of healthy-minded religion. The philosophy of healthy-minded religion is not one of struggle but of surrender and letting go; this is the route to physical and spiritual health. James finishes his fifth lecture with a note about positivist scientists who simply regard religion as an evolutionary survival mechanism. While not explicitly endorsing mind-cure, James argues that its growth should warn against the most positivistic and sectarian scientists who see nothing of value in religion.

Lectures VI And VII. The Sick Soul.

Lectures VI and VII complete James's typology of religion by considering sick souled religion. James makes the contrast between the two religious approaches by considering their different responses to the problem of evil: whereas the healthy-minded believer is untroubled by the existence of evil and simply chooses to have no dealings with it, this option is not available to the sick souled believer, for whom the world's evils cannot be ignored. For the religion of the sick soul, evil is an unavoidable and even essential part of human existence and this makes straightforward religious acceptance of the world difficult. James describes an experience of the world utterly stripped of all its emotional valence, transforming all experience into melancholy. To illustrate this, James quotes from Leo Tolstoy's short work My Confession, which describes Tolstoy's experience of utter meaninglessness, and John Bunyan's autobiographical account of melancholy, which was bound up with Bunyan's perception of his original sin. James's third example is an unnamed source (which is in fact autobiographical)[4] who describes overwhelming panic and fear who felt utter dread at his own existence. Throughout the discussion of these examples, James indicates that all three recovered from their melancholy but that discussion of this will be postponed until later lectures. James concludes the lecture by considering the possible disagreement that could arise between healthy-minded and sick souled religious believers; James argues that, while healthy-minded religions can be completely satisfying for some people, they are ill-equipped to deal with suffering. Therefore, the best religions are, in James's view, those such as Buddhism and Christianity which can accommodate evil and suffering by teaching a path of deliverance.

Lecture VIII. The Divided Self, and the Process of Its Unification.

James begins this lecture by rehearsing the arguments of the previous lectures on healthy-mindedness and sick soul. He notes that, while a healthy-minded individual can achieve happiness through a surplus of positive experience over negative, this is not available to the sick soul. The sick soul is so burdened by the despair and transience of natural life that it takes a spiritual transformation to overcome this melancholy. James argues that the experience of a sick soul is psychologically rooted in an individual having a disordered constitution, presented in the lecture as the presence of two conflicting selves in a person. Normal personal development consists in the unifying of these two selves but this is not always successful and the period of unification is characterised by unhappiness. James notes that for those with a more religious disposition, this disunity will be experienced as religious melancholy or conviction of sin, and suggests Saint Augustine and Henry Alline as examples of religiously divided souls who eventually achieved inner unity through religious conversion. James notes that religious conversion can occur either gradually or suddenly, before returning to the examples of Tolstoy and Bunyan, who both exemplify the gradual approach. The root of the sickness of these two souls can be found, James argues, in their inner disunity and thus was overcome by a process of unification — or religious conversion. Despite the unification of their souls, neither Tolstoy nor Bunyan have become healthy-minded: James argues that the previous experiences of both preclude this categorisation; rather, they are twice-born.

Lecture IX. Conversion.

After discussing the unification of the disordered soul, James moves on to discuss the specifically religious instances of this phenomenon, the phenomenon of conversion. Two lectures are devoted to this subject which, in the published volume, are presented as two separate chapters. To introduce the idea of conversion, James begins by quoting at length the testimony of an individual named Stephen H. Bradley, who experienced a dramatic conversion experience at the age of fourteen after attending a Methodist revival meeting. James then proceeds to discuss the ways in which an individual's character can develop according to the specifics of their life and argues that such changes occur as a result of changing "emotional excitement" in one's life,[5] whereby things which once excited an individual's emotions no longer do so, or vice versa. Therefore, for James, to be converted means that religious ideas move from a peripheral place in one's consciousness to center stage and that these religious ideas begin to take a central role in the convert's energy and motivation. As to why this change takes place, James notes that psychology cannot provide a clear answer but suggests the symbolism of mechanical equilibrium could help to provide an answer. Following E. D. Starbuck, James makes a distinction between volitional conversion, wherein a convert consciously chooses to convert, and self-surrender conversion, which involves a convert letting go and allowing themselves to be converted. Volitional conversions are more gradual than self-surrender conversions, the latter of which are more likely to involve dramatic conversion experiences and, James argues, are the more interesting objects of study. Since all religion involves reliance on a power higher than oneself, James finds that a degree of self-surrender is a necessary part of all religious conversion — and that theology and psychology agree on this point.

Lecture X. Conversion—Concluded.

The second lecture on conversion continues the discussion of sudden and dramatic conversion, which involves a radical transformation from the old life to the new, supported with a number of examples. Sudden conversion experiences can be noted, James argues, for the sense of passivity felt by the convert during the process, a sense which Christian theology interprets as the action of the spirit of God in which a wholly new nature is given to the convert. James then compares different Christian traditions on the notion of instantaneous conversion: more traditional Protestants as well as Catholics do not value instantaneous conversions, whereas other groups — such as Moravian Protestants and Methodists — invest high value in such experiences. To explain the human capacity for dramatic conversion experiences, James refers to the notion in nineteenth-century psychology of consciousness as a field. The field of consciousness is analogous to a magnetic field, with the conscious subject at the center, the borders of which are hazy and indeterminate. Events which occur at the margins of the field of consciousness, or subconsciously, can in James's view explain various kinds of mystical and religious experiences. Taken psychologically, the individuals who experience instantaneous conversion can be described as having unusually large margins in their fields of consciousness. Anticipating an objection from religious listeners, James then refers to his earlier comment concerning the distinction between a phenomenon's value and its origin: the value of a religious experience is established not by tracing the source of its origin but in evaluating its fruits. On examining the fruits of conversion, James finds that, while there is nothing which positively distinguishes converted people from their non-converted counterparts as a whole, for the individual converts, such experiences precipitate a renewed spiritual and moral life. James finishes this lecture by noting key characteristics of sudden conversion experiences: a sense of assurance in submission to a higher power, the perception of truths not previously known, and a change in how the perceived world appears to the individual. James finally makes a brief note on the issue of backsliding, arguing that conversion experiences present a kind of "high water mark", which cannot be diminished by backsliding.[6]

Lectures XI, XII, And XIII. Saintliness.

Having concluded the preceding lecture arguing that the value of a conversion experience can be judged according to the fruits it produces in an individual's life, James proceeds to evaluate these fruits in his lectures on saintliness. James analyses a person's character as derived from the interaction between the internal forces of impulse and inhibition; while these are often in conflict, inhibitions can be overcome when emotions reach a certain level of high intensity. The religious disposition is interpreted in this way: religious emotions form the center of an individual's emotional energy and thus have the power to overwhelm one's inhibitions. This is why conversion can result in individual character change, and James offers various examples of individuals cured of vices such as drunkenness and sexual immorality following their conversion.

A saintly character is one where "spiritual emotions are the habitual centre of the personal energy." James states that saintliness includes: "1. A feeling of being in a wider life than that of this world's selfish little interests; and a conviction … of the existence of an Ideal Power. 2. A sense of the friendly continuity of the ideal power with our own life, and a willing self-surrender to its control. 3. An immense elation and freedom, as the outlines of the confining selfhood melt down. 4. A shifting of the emotional Centre towards loving and harmonious affections, towards 'yes, yes' and away from 'no,' where the claims of the non-ego are concerned."

This religious character can be broken down into asceticism (pleasure in sacrifice), strength of soul (a "blissful equanimity" free from anxieties), purity (a withdrawal from the material world), and charity (tenderness to those most would naturally disdain). The rest of the lectures are devoted to numerous examples of these four kinds of saintliness, exemplified by numerous religious figures across various traditions. This includes an extended discussion of various ascetic practices, ranging from a resistance to excess comfort through to more extreme forms of self-mortification, such as that practiced by Henry Suso. James then discusses the monastic virtues of obedience, chastity and poverty, and finishes the lecture by noting that the value of saintly virtues can only truly be understood by those who have experienced them.

Lectures XIV And XV. The Value of Saintliness.

In these lectures, James considers the question of how to measure the value of saintliness without addressing the question of the existence of God (which is prohibited by James's empirical method). This can be done, James insists, by considering the fruits (or benefits) derived from saintliness. James then restates his decision to focus on the private, inner experience of religion; he quotes a personal experience of George Fox, noting that such experiences will initially be treated as heterodoxy and heresy but, with enough of a following, can become a new orthodoxy. Responding to the question of extravagance, James notes that saintly virtues are liable to corruption by excess which is often the result of a deficient intellect being overcome by the strength of the saintly virtue. Saintly devotion can become fanaticism or, in gentler characters, feebleness derived from over-absorption, to the neglect of all practical interests. Excessive purity can become scrupulosity and can result in withdrawal from society. Finally, James finds the virtues of tenderness and charity ill-equipped for a world in which other people act dishonestly. Despite these tendencies to excess, James finds that the saintly virtues can often operate prophetically, demonstrating the capacity human beings have for good. Even asceticism, which James acknowledges can often appear to be an excess with no redeeming virtue, can work in a similar way. The excesses of the ascetic can be an appropriate response to the world's evils and remind the more healthy-minded individuals of the world's imperfection. After briefly rejecting a Nietzschean critique of saintliness, James concludes that, while saints may often appear ill-adapted to society, they may be well-adapted to the future heavenly world. Hence, the value of saintliness cannot be answered without a return to questions of theology.

Lectures XVI And XVII. Mysticism.

James begins his lectures on mysticism by reiterating his claim that mystical experiences are central to religion. He then outlines four features which mark an experience as mystical. The first two are sufficient to establish that an experience is mystical:

- Ineffability — "no adequate report of its contents can be given in words. […] its quality must be directly experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred to others. […] mystical states are more like states of feeling than like states of intellect. No one can make clear to another who has never had a certain feeling, in what the quality or worth of it consists."

- Noetic quality —"Although so similar to states of feeling, mystical states seem to those who experience them to be also states of knowledge. They are states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect. They are illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance, all inarticulate though they remain; and as a rule they carry with them a curious sense of authority for after-time."

The second two are very often found in mystical experiences:

- Transiency —"Mystical states cannot be sustained for long."

- Passivity —"the mystic feels as if his own will were in abeyance, and indeed sometimes as if he were grasped and held by a superior power."

During a discussion about mystical experiences precipitated by the consumption of alcohol or psychoactive drugs, James comments that he regards ordinary waking sober consciousness as just one kind of consciousness among many and he goes on to argue that the kind of consciousness brought about by the consumption of psychoactive drugs is the same as that which has been cultivated by the mystical traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and Christianity. Having surveyed examples of mystical experience, James proceeds to consider their veracity. In mysticism's favour is James's observation that mystical experiences across diverse traditions tend to point towards the same kind of truth, that is, the existence of a greater, incomprehensible reality, beyond human experience. The knowledge imparted by mystical experience is, on the whole, "optimistic" and "pantheistic".[7] Regarding the authoritativeness of mystical experiences, James makes three points: first, mystical experiences are authoritative for the individuals who experience them; second, they have no authority over someone who has not had the experience; third, despite this, mystical experiences do indicate that the rationalistic consciousness does not have sole authority over matters of truth.

Lecture XVIII. Philosophy.

James's lecture on philosophy returns to the question of whether religious experiences can justify belief in God, having found in the previous lecture that mysticism can only validate religion for those who have mystical experiences. James then argues that feelings are fundamental to religion: philosophy and theology would never have started had there not been felt experiences to prompt reflection. His intention is to challenge intellectualized religion, the view of rationalist theologians such as John Henry Newman that religion can (and must) be rationally demonstrated, independent of any private feeling. Following a discussion of Charles Peirce's pragmatist philosophy, James argues that neither the traditional metaphysical nor moral characteristics of God proposed by theology can be supported by religious experience and thus they must be disposed of. James's conclusion with regards to philosophy is that it is ultimately incapable of demonstrating by purely rational processes the truth of religion. Transformed into a "Science of Religions", however, philosophy can be useful in critiquing various extant religious beliefs by comparing religions across cultures and demonstrating where these religions are contradicted by the natural sciences.[8]

Lecture XIX. Other Characteristics.

In this penultimate lecture, James considers some other characteristics of religion left over from the preceding lectures. The first in that the aesthetic sentiments involved in religion can make religions appear more attractive to people: the richness of complex systems of dogmatic theology can be equated to the majesty of religious architecture. After briefly commenting that sacrifice and confession are rarely practiced in contemporary religion, James discusses at greater length the phenomenon of prayer which, he argues, is the means by which religious people communicate with God. Acknowledging challenges to the authenticity of petitionary prayer, James argues that prayers are often answered through some inner resourcing of the individual (such as strength to endure a trial). Thus, prayer does effect real change - whether than change is objective or subjective is of no consequence to James. In the final part of the lecture, James draws parallels between what is often regarded as spiritual inspiration and the manifestations of psychopathological symptoms; he rejects the notion that religious experiences can be explained away as psychopathology and rather insists that both religious experiences and psychopathology indicate the existence of a reality beyond what is normally experienced by sober, awake, rational consciousness.

Lecture XX. Conclusions.

In the final chapter James identifies a two-part "common nucleus" of all religions: (1) an uneasiness ("a sense that there is something wrong about us as we naturally stand") and (2) a solution ("a sense that we are saved from the wrongness by making proper connection with the higher powers").

Postscript

James finds that "the only thing that [religious experience] unequivocally testifies to is that we can experience union with something larger than ourselves and in that union find our greatest peace." He explains that the higher power "should be both other and larger than our conscious selves."

Themes[]

Religious experiences[]

In the Varieties, James explicitly excludes from his study both theology and religious institutions, choosing to limit his study to direct and immediate religious experiences, which he regarded as the more interesting object of study.[9] Churches, theologies, and institutions are important as vehicles for passing on insights gained by religious experience but, in James's view, they live second-hand off the original experience of the founder.[10] A key distinction in James's treatment of religion is between that of healthy-minded religion and religion of the sick soul; the former is a religion of life's goodness, while the latter cannot overcome the radical sense of evil in the world.[9] Although James presents this as a value-neutral distinction between different kinds of religious attitude, he in fact regarded the sick souled religious experience as preferable, and his anonymous source of melancholy experience in lectures VI and VII is in fact autobiographical.[4] James considered healthy mindedness to be America's main contribution to religion, which he saw running from the transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman to Mary Baker Eddy's Christian Science. At the extreme, the "healthy minded" see sickness and evil as an illusion. James considered belief in the "mind cure" to be reasonable when compared to medicine as practiced at the beginning of the twentieth century.[11]

James devotes two lectures to mysticism and in the lectures outlines four markers of mystical experience. These are:

- Ineffable: the experience is incapable of being described and must be directly experienced to be understood.

- Noetic: the experience is understood to be a state of knowledge through which divine truths can be learned.

- Transient: the experience is of limited duration.

- Passivity: the subject of the experience is passive, unable to control the arrival and departure of the experience.[9]

He believed that religious experiences can have "morbid origins"[12] in brain pathology and can be irrational but nevertheless are largely positive. Unlike the bad ideas that people have under the influence of a high fever, after a religious experience the ideas and insights usually remain and are often valued for the rest of the person's life.[13]

James had relatively little interest in the legitimacy or illegitimacy of religious experiences. Further, despite James' examples being almost exclusively drawn from Christianity, he did not mean to limit his ideas to any single religion. Religious experiences are something that people sometimes have under certain conditions. In James' description, these conditions are likely to be psychological or pharmaceutical rather than cultural.

Pragmatism[]

Although James did not fully articulate his pragmatic philosophy until the publication of Pragmatism in 1907, the approach to religious belief in the Varieties is influenced by pragmatic philosophy. In his Philosophy and Conclusions lectures, James concludes that religion is overall beneficial to humankind, although acknowledges that this does not establish its truth.[9] While James intended to approach the topic of religious experience from this pragmatist angle, Richard Rorty argues that he ultimately deviated from this methodology in the Varieties. In his lectures on saintliness, the intention is to discover whether the saintly virtues are beneficial for human life: if they are then, according to pragmatism, that supports their claim to truth. However, James ends up concluding that the value of the saintly virtues is dependent on their origin: given that the saintly virtues are only beneficial if there is an afterlife for which they can prepare us, their value depends on whether they are divinely ordained or the result of human psychology. This is no longer a question of value but of empirical fact. Hence, Rorty argues that James ends up abandoning his own pragmatist philosophy due to his ultimate reliance of empirical evidence.[14]

James considers the possibility of "over-beliefs", beliefs which are not strictly justified by reason but which might understandably be held by educated people nonetheless. Philosophy can contribute to shaping these over-beliefs — for example, he finds wanting traditional arguments for the existence of God, including the cosmological, design, and moral arguments, along with the argument from popular consensus.[15] James admits to having his own over-belief, which he does not intend to prove, that there is a greater reality not normally accessible by our normal ways of relating to the world which religious experiences can connect us to.[9]

Reception[]

The August 1902 New York Times review of the first edition ends with the following:

Everywhere there is a frolic welcome to the eccentricities and extravagances of the religious life. Many will question whether its more sober exhibitions would not have been more fruitful of results, but the interest and fascination of the treatment are beyond dispute, and so, too, is the sympathy to which nothing human is indifferent.[1]

A July 1963 Time magazine review of an expanded edition published that year ends with quotes about the book from Peirce and Santayana:[16]

In making little allowance for the fact that people can also be converted to vicious creeds, he acquired admirers he would have deplored. Mussolini, for instance, hailed James as a preceptor who had showed him that "an action should be judged by its result rather than by its doctrinary basis." James ... had no intention of giving comfort to latter-day totalitarians. He was simply impatient with his fellow academicians and their endless hairsplitting over matters that had no relation to life. A vibrant, generous person, he hoped to show that religious emotions, even those of the deranged, were crucial to human life. The great virtue of The Varieties, noted pragmatist philosopher Charles Peirce, is its "penetration into the hearts of people." Its great weakness, retorted George Santayana, is its "tendency to disintegrate the idea of truth, to recommend belief without reason and to encourage superstition."

In 1986, Nicholas Lash criticised James's Varieties, challenging James's separation of the personal and institutional. Lash argues that religious geniuses such as St. Paul or Jesus, with whom James was particularly interested, did not have their religious experiences in isolation but within and influenced by a social and historical context.[17] Ultimately, Lash argues that this comes from James's failure to overcome Cartesian dualism in his thought: while James believed he had succeeded in surpassing Descartes, he was still tied to a notion of an internal ego, distinct from the body or outside world, which undergoes experiences.[18]

Cultural references[]

The famous 1932 dystopian novel Brave New World by Aldous Huxley has a passage where Mustapha Mond shows this and other books about religion to John, after the latter has been caught for causing disorder between Delta humans in a hospital.

The book is referenced twice in the 1939 “The Big Book” of Alcoholics Anonymous, which is the basic text for members in Alcoholics Anonymous.

In 2012 the Russian-American composer Gene Pritsker released his chamber opera William James's Varieties of Religious Experience.

The 2015 The Man in the High Castle TV series season 2, episode 2, includes this as a book banned by the Japanese, who occupy the former western United States after World War II. One of the characters studies the book as he tries to understand his brief transport to what, for him, is the alternate reality of the United States having won World War II.

The book also appears in the new 2021 , as King Shark reads it upside down.

See also[]

- Cosmic Consciousness

- Fideism

- Mysticism

- Religious experience

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A Study of Man: The Varieties of Religious Experience". The New York Times. August 9, 1902. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ Poole, Randall A (2003). "William James in the Moscow Psychological Society". In Grossman, Joan DeLaney; Rischin, Ruth (eds.). William James in Russian Culture. Lanham MD: Lexington Books. p. 143. ISBN 978-0739105269.

- ^ James, William (2012). Bradley, Matthew (ed.). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 32.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taylor, Charles (2003). Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press. pp. 33–34.

- ^ James, William (2012). Bradley, Matthew (ed.). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 154.

- ^ James, William (2012). Bradley, Matthew (ed.). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 200.

- ^ James, William (2012). Bradley, Matthew (ed.). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 322.

- ^ James, William (2012). Bradley, Matthew (ed.). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 347.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Goodman, Russell (2017). "William James". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ^ Taylor, Charles (2003). Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press. pp. 23.

- ^ Duclow, Donald F. (2002-01-01). "William James, Mind-Cure, and the Religion of Healthy-Mindedness". Journal of Religion and Health. 41 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1023/A:1015106105669. JSTOR 27511579. S2CID 34501644.

- ^ Fuller, Andrew Reid (1994-01-01). Psychology and Religion: Eight Points of View. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780822630364.

- ^ James, William (1985-01-01). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674932258.

feverish%20fancies.

- ^ Rorty, Richard (2004). "Some Inconsistencies in James's Varieties". In Proudfoot, Wayne (ed.). William James and a Science of Religions: Reexperiencing The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 86–97 (95). ISBN 9780231132046.

- ^ Pomerleau, Wayne P. "William James (1842—1910)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ "Books: The Waterspouts of God". Time. July 19, 1963. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ Lash, Nicholas (1986). Easter in Ordinary: Reflections on Human Experience and the Knowledge of God. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. pp. 54–57.

- ^ Lash, Nicholas (1986). Easter in Ordinary: Reflections on Human Experience and the Knowledge of God. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. pp. 60–64.

External links[]

- The Varieties of Religious Experience at Project Gutenberg

- Tom Butler-Bowdon (2005), "Short commentary on The Varieties of Religious Experience", 50 Spiritual Classics: 50 Great Books of Inner Discovery, Enlightenment and Purpose, London & Boston: Nicholas Brealey

- Internet Archive listings for Varieties of Religious Experience

- 1902 non-fiction books

- Books by William James

- English-language books

- Epistemology literature

- Epistemology of religion

- Gifford Lectures

- History of mental health in the United Kingdom

- History of psychiatry

- History of psychology

- Philosophy of psychology

- Philosophy of religion literature

- Psychology of religion

- University of Edinburgh