Theodore von Kármán

Theodore von Kármán | |

|---|---|

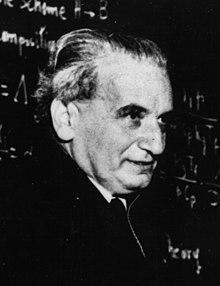

Von Kármán at the Caltech Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1950 | |

| Born | May 11, 1881 Budapest, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | May 6, 1963 (aged 81) Aachen, West Germany |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Citizenship | Hungary United States |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Kármán vortex street von Kármán constant von Kármán swirling flow von Kármán momentum integral Kármán line Kármán–Howarth equation Supersonic and hypersonic airflow characterization; |

| Awards | ASME Medal (1941) John Fritz Medal (1948) Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy (1954) Daniel Guggenheim Medal (1955) Timoshenko Medal (1958) National Medal of Science (1962) Wilhelm Exner Medal (1962) Foreign Member of the Royal Society[1] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Aerospace Engineering |

| Institutions | University of Göttingen, RWTH Aachen, California Institute of Technology, von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics |

| Thesis | Investigations on buckling strength (1908) |

| Doctoral advisor | Ludwig Prandtl[2] |

| Doctoral students | Giuseppe Gabrielli (1926) Wolfgang Klemperer (1926) Richard G. Folsom (1932) Maurice Anthony Biot (1932) Frank Wattendorf (1933) Ernest Sechler (1934) Arthur T. Ippen (1936) Qian Xuesen (1938) Louis Dunn (1940) Frank Malina (1940) Homer J. Stewart (1940) Guo Yonghuai (1944) Chia-Chiao Lin (1944) Sol Penner (1946) Wallace D. Hayes (1947) Frank E. Marble(1947)[2] |

| Influenced | Gregorio Millán |

Theodore von Kármán (Hungarian: (Szőlőskislaki) Tódor Kármán [(søːløːʃkiʃlɒki) ˈkaːrmaːn ˈtoːdor]; 11 May 1881 – 6 May 1963) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer, and physicist who was active primarily in the fields of aeronautics and astronautics. He was responsible for many key advances in aerodynamics, notably on supersonic and hypersonic airflow characterization. He is regarded as an outstanding aerodynamic theoretician of the 20th century.[3][4][5][6]

Early life[]

Theodore von Kármán was born into a Jewish family in Budapest, Austria-Hungary as Kármán Tódor, the son of Helen (Kohn, Hungarian: Kohn Ilka[7]) and Mór Kármán.[8] One of his ancestors was Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel.[1] He studied engineering at the city's Royal Joseph Technical University, known today as Budapest University of Technology and Economics. After graduating in 1902 he moved to the German Empire and joined Ludwig Prandtl at the University of Göttingen, where he received his doctorate in 1908. He taught at Göttingen for four years. In 1912 he accepted a position as director of the Aeronautical Institute at RWTH Aachen University, a leading German university. His time at RWTH Aachen was interrupted by service in the Austro-Hungarian Army from 1915 to 1918, when he designed the Petróczy-Kármán-Žurovec, an early helicopter.

After the war he returned to Aachen with his mother and sister Josephine de Karman. Some of his students took an interest in gliding and saw the competitions of the Rhön-Rossitten Gesellschaft as an opportunity to advance in aeronautics. Kármán engaged Wolfgang Klemperer to design a competitive glider.[9]

Josephine encouraged her brother Theodore to expand his science beyond national boundaries. They organized the first international conference in mechanics held in September 1922 in Innsbruck. Subsequent conferences were organized as the International Union of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics.[10] Kármán left his post at RWTH Aachen in 1930.

Emigration and JPL[]

Apprehensive about developments in Europe regarding Nazism, in 1930 Kármán accepted the directorship of the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology (GALCIT). The directorship included provision for a research assistant, and he selected Frank Wattendorf, an American who had been studying for three years in Aachen.

Another student Ernest Edwin Sechler took up the problem of making reliable airframes for aircraft, and with Kármán's support, developed an understanding of aeroelasticity.

In 1936, Kármán engaged the legal services of Andrew G. Haley to form the Aerojet Corporation, with his graduate student Frank Malina and their experimental rocketry collaborator Jack Parsons, to manufacture JATO rocket motors. He later became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

German activity during World War II increased US military interest in rocket research. In early 1943, the Experimental Engineering Division of the United States Army Air Forces Material Command forwarded to Kármán reports from British intelligence sources describing German rockets capable of travelling more than 100 miles (160 km). In a letter dated 2 August 1943 Kármán provided the Army with his analysis of and comments on the German program.[11]

In 1944 he and others affiliated with GALCIT founded the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which is now a Federally funded research and development center managed and operated by Caltech under a contract from NASA. In 1946 he became the first chairman of the Scientific Advisory Group which studied aeronautical technologies for the United States Army Air Forces. He also helped found AGARD, the NATO aerodynamics research oversight group (1951), the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences (1956), the International Academy of Astronautics (1960), and the Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics in Sint-Genesius-Rode, south of Brussels (1956).

He eventually became an important figure in supersonic motion, noting in a seminal paper that aeronautical engineers were "pounding hard on the closed door leading into the field of supersonic motion."[12]

Last years[]

In June 1944, von Kármán underwent surgery for intestinal cancer in New York City. The surgery caused two hernias, and Kármán's recovery was slow. Early in September, while still in New York, he met US Army Air Forces Commanding General Henry H. Arnold on a runway at LaGuardia Airport, and Arnold then proposed that Kármán should move to Washington, D.C. to lead the Scientific Advisory Group and become a long-range planning consultant to the military. Kármán returned to Pasadena around mid-September, was appointed to the SAG position on October 23, 1944, and left Caltech in December 1944.[13]

At the age of 81 Kármán was the recipient of the first National Medal of Science, bestowed in a White House ceremony by President John F. Kennedy. He was recognized, "For his leadership in the science and engineering basic to aeronautics; for his effective teaching and related contributions in many fields of mechanics, for his distinguished counsel to the Armed Services, and for his promoting international cooperation in science and engineering."[14]

Kármán never married. He died on a trip to Aachen, West Germany, in 1963, five days short of his 82nd birthday,[15] and his body was returned to the United States to be entombed in the Beth Olam Mausoleum at what is now the Hollywood Forever Cemetery.[16] He has sometimes been described as one of The Martians.[17]

Kármán's fame was in the use of mathematical tools to study fluid flow,[18] and the interpretation of those results to guide practical designs. He was instrumental in recognizing the importance of swept-back wings ubiquitous in modern jet aircraft.

Selected contributions[]

Specific contributions include theories of non-elastic buckling, unsteady wakes in circum-cylinder flow, stability of laminar flow, turbulence, airfoils in steady and unsteady flow, boundary layers, and supersonic aerodynamics. He made additional contributions in other fields, including elasticity, vibration, heat transfer, and crystallography. His name also appears in a number of concepts, for example:

- Föppl–von Kármán equations (large deflection of elastic plates)

- Born–von Karman boundary condition (in solid state physics)

- Born–von Kármán lattice model (model for the lattice dynamics of a crystal)

- Chaplygin–Kármán–Tsien approximation (potential flow)

- Falkowich–Kármán equation (transonic flow)

- von Kármán constant (wall turbulence)

- Kármán line (aerodynamics/astronautics)

- von Kármán–Gabrielli diagram (transportation)

- Kármán–Howarth equation (turbulence)

- k function

- Kármán–Penner flux fraction (combustion)

- Kármán–Nikuradse correlation (viscous flow; coauthored by Johann Nikuradse)

- Kármán–Pohlhausen parameter (boundary layers)

- Kármán–Treffz transformation (airfoil theory)

- Prandtl–von Kármán law (velocity in open channel flow)

- von Kármán integral equation (boundary layers)

- von Kármán ogive (supersonic aerodynamics)

- von Kármán vortex street (flow past cylinder)

- von Kármán–Tsien compressibility correction

- Vortex shedding

- Von Kármán swirling flow

Selected writings[]

Books[]

- von Kármán, Theodore; Burgers, J. M. (1924). General Aerodynamic Theory. 2 vols., Julius Springer.

- von Kármán, Theodore; Biot, M. A. (1940). Mathematical Methods in Engineering; An introduction to the Mathematical Treatment of Engineering Problems. McGraw-Hill. pp. 505. ASIN B0006AOTLK.

- von Kármán, Theodore; Biot, M. A. (2004). Aerodynamics: Selected Topics in the Light of Their Historical Development. Dover Books on Aeronautical Engineering. Dover Publications. p. 224. ISBN 978-0486434858.

- von Kármán, Theodore (1956). Collected Works of Dr. T. von Kármán (1902–1951). 4 vols., Butterworth Scientific Publications.

- von Kármán, Theodore (1961). From Low-Speed Aerodynamics to Astronautics. Pergamon Press. ASIN B000H4OVPO.

- von Kármán, Theodore; Edson, L. (1967). The Wind and Beyond—T. von Kármán Pioneer in Aviation and Pathfinder in Space. Little Brown. p. 376. ISBN 978-0316907538.

Autobiography[]

Four years after Kármán died his autobiography The Wind and Beyond was published by Lee Edson with Little, Brown and Company. Seven major academic journals then followed with book reviews by noted authors: As the book was non-technical, written for the general reader, Thomas P. Hughes[19] cited that as problematic given the technical context of Kármán's work. Hughes conceded that Kármán "exhibited a genius for finding the simplifying assumptions that made possible the mathematical analysis." While acknowledging Kármán's gifts as an applied mathematician and teacher, Stanley Corrsin points out that the autobiography is "marriage between a man and his ego." In the later part of his life, Kármán was a "planner of global symposia and societies" and a "consultant to the upper echelons of the Pentagon corps."[20]

On creativity, Kármán wrote "the finest creative thought comes not out of organized teams but out of the quiet of one's own world."[9]:307 In his review[21] I. B. Holley noted "penetrating insights into the creative process, its ingredients, nurture and exploitation." According to Holley, Kármán was given to "convivial drinking and the company of beautiful women."

An enthusiastic review by J. Kestin[22] advised readers to buy and study the book, and prize it as a reference. On the other hand, Charles Süsskind[23] faults Kármán for his contempt for the conventional (gaminarie). Süsskind expected the book to show some reaction to Wernher von Braun’s coming to America, and some clarification of the Hsue-shen Tsien affair, rather than "lapses into generalities". Süsskind also tags Kármán as a militarist: a "forthright engineer who is quite unabashed about his lifelong association with military authorities in whatever country he happened to reside at the time."

Sydney Goldstein, who also wrote the Royal Society memoir for Kármán, reviewed the autobiography[24] and remembered "an eminent engineer and scientist, warm-hearted and witty, much traveled, well-known by many, devoted to international collaboration, who, in his own words, as a scientist found the military 'the most comfortable group to deal with'".

Honors and legacy[]

- Each year since 1960 the American Society of Civil Engineers has awarded to an individual the Theodore von Karman Medal, "in recognition of distinguished achievement in engineering mechanics."[25]

- Established in 1968, the Theodore von Kármán Prize has been awarded by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics to recognize outstanding application of mathematics in mechanics or engineering.

- In 1968, Kármán was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame.[26]

- Established in 1983, the has been awarded annually by the International Academy of Astronautics to recognize outstanding lifetime achievements in any branch of science without limit of nationality or sex.[27]

- In 2005 Kármán was named as an Honorary Fellow of the Arnold Engineering Development Center (AEDC). Fellows of the AEDC are recognized as "People who have made exceptionally distinguished contributions to the center's flight testing mission."[28]

- Craters on Mars and the Moon are named in his honor.

- The boundary between the atmosphere and space is named the Kármán line.

- In Irvine, CA there is a five-mile street in the heart of Irvine's business center named after him.

- In 1977, RWTH Aachen University named its newly constructed lecture hall complex "Kármán-Auditorium" in memory of Kármán's outstanding research contributions at the university's Aeronautical Institute.

- An auditorium at JPL is named after Kármán,[29] as is a series of monthly lectures held there since 2007.[30]

- An auditorium at AFRL is named after Arnold and Kármán.

- University of Southern California Professor Shirley Thomas (after nearly two decades of petitioning) was able to create a postage stamp in his honor.[31]

- In 1963 President Kennedy awarded Kármán the National Medal of Science: "Dr. von Karman, it is a great pleasure for me to select you as the first recipient of the National Medal of Science. I know of no one else who more completely represents all of the areas with which this award is appropriately concerned—science, engineering, and education."[32]

- In 1957, Kármán became the first recipient of the Ludwig-Prandtl-Ring from Deutsche Gesellschaft für Luft- und Raumfahrt (German Society for Aeronautics and Astronautics) for "outstanding contribution in the field of aerospace engineering."

- In 1956 Kármán founded a research institute in Sint-Genesius-Rode, Belgium, which is now named after him: the von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics.

- In 1948 Kármán was awarded the Franklin Medal.

- The American Mathematical Society selected Kármán as its Josiah Willard Gibbs Lecturer for 1939.[33][34]

- The International von Kármán Wings Award Banquet is an annual affair.[35]

- The only still airworthy Lisunov Li-2 plane (reg. HA-LIX) has been named Kármán Tódor in 2002.[36]

See also[]

- The Martians (scientists)

- Karman line

Further reading[]

- I. Chang, Thread of the Silkworm. Perseus Books Group (1995). ISBN 0-465-08716-7.

- D. S. Halacy, Jr., Father of Supersonic Flight: Theodor von Kármán (1965).

- M. H. Gorn, The Universal Man: Theodore von Kármán's Life in Aeronautics (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, 1992).

- G. Gabrielli, "Theodore von Kármán", Atti Accad. Sci. Torino Cl. Sci. Fis. Mat. Natur. 98 (1963/1964), 471–485.

- J. L. Greenberg and J. R. Goodstein, "Theodore von Kármán and applied mathematics in America," A century of mathematics in America II (Providence, R.I., 1989), 467–477.

- R. C. Hall, "Shaping the course of aeronautics, rocketry, and astronautics: Theodore von Kármán, 1881–1963," J. Astronaut. Sci. 26 (4) (1978), 369–386.

- J. Polásek, "Theodore von Kármán and applied mathematics" (Czech), Pokroky Mat. Fyz. Astronom. 28 (6) (1983), 301–310.

- Wattendorf, F. L. (1956). "Theodore von Kármán, international scientist". Z. Flugwiss. 4: 163–165.

- Wattendorf, F. L.; Malina, F. J. (1964). "Theodore von Kármán, 1881–1963". Astronautica Acta. 10: 81.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goldstein, S. (1966). "Theodore von Karman 1881–1963". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 12: 334–365. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1966.0016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Theodore von Kármán at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ Chang, Iris, Thread of the silkworm, Basic Books, 1996, pages 47–60

- ^ Greenberg, J. L.; Goodstein, J. R. (1983). "Theodore von Karman and Applied Mathematics in America". Science. 222 (4630): 1300–1304. Bibcode:1983Sci...222.1300G. doi:10.1126/science.222.4630.1300. PMID 17773321. S2CID 19738034.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Theodore von Kármán", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Sears, W. R. (1965). "Some Recollections of Theodore von Kármán". Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. 13: 175–183. doi:10.1137/0113011.

- ^ Örvények és Repülők-Kármon Tódor Élete és Munkássága, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 1994 Lee Edson, p.12., ISBN 9630567644 - Hungarian edition of Theodore von Kármán with Lee Edson (1967) The Wind and Beyond

- ^ "Theodore von Karman - Rocket Scientist". Resonance. August 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Theodore von Kármán with Lee Edson (1967) The Wind and Beyond, page 98

- ^ Alkemade, Dr. Ir. Fons (2010). "IUTAM | History". Amsterdam, The Netherlands: International Union of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ "Development of the Corporal: the embryo of the army missile program, vol. 1" (PDF). Army Ballistic Missile Agency. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26.

- ^ Hallion, Richard P. "The NACA, NASA, and the Supersonic-Hypersonic Frontier". NASA. NASA Technical Reports Server. hdl:2060/20100025896.

- ^ Bluth, John (July 15, 1994). "Von Karman, Malina laid the groundwork for the future JPL". Jet Propulsion Laboratory UNIVERSE. 24 (14).

- ^ "The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details". NSF.

- ^ Physics Today

- ^ Legends of Hollywood Forever Cemetery

- ^ A marslakók legendája - György Marx

- ^ Sears, W. R. (1986). "Von Kármán: Fluid Dynamics and Other Things". Physics Today. 39 (1): 34. Bibcode:1986PhT....39a..34S. doi:10.1063/1.881063.

- ^ Thomas P. Hughes (1968) The American Historical Review

- ^ Stanley Corrsin (1968) Isis 59(2)

- ^ I. B. Holley (1968) Science v 159 #3814

- ^ J. Kestin (1969) Journal of Applied Mechanics 36(1)

- ^ Charles Süsskind (1968) Technology and Culture

- ^ Sydney Goldstein (1968) Journal of Fluid Mechanics 33(2) doi:10.1017/S0022112068221390

- ^ "Theodore von Karman Medal". ASCE. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30.

- ^ Sprekelmeyer, Linda, editor. These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame. Donning Co. Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57864-397-4.

- ^ "von Karman Award". International Academy of Astronautics.

- ^ "AEDC Fellows". Arnold Air Force Base.

- ^ Bilger, Burkhard (April 22, 2013) "The Martian Chroniclers", The New Yorker. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- ^ "Von Kármán Lecture Series".

- ^ "1992 29¢ Theodore von Karman Stamps Scott #2699". Exploring Space Stamps.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (February 18, 1963) "Remarks Upon Presenting the National Medal of Science to Theodore von Karman". The American Presidency Project.

- ^ Josiah Willard Gibbs Lectures. American Mathematical Society

- ^ von Kármán, Theodore (1940). "The engineer grapples with nonlinear problems". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 46 (8): 615–683. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1940-07266-0. MR 0003131.

- ^ http://galcit.caltech.edu/ahs/index.html

- ^ Fontos események li-2.hu, retrieved 10 June 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theodore von Kármán. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Theodore von Kármán |

- Works by or about Theodore von Kármán at Internet Archive

- Judith R. Goodstein and Carolyn Kopp (1981) Guide to the Von Kármán Collections, Institute Archives, Robert A. Millikan Library, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Theodore von Kármán", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- JPL Director 1938-44 from Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- The Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics in Belgium

- Theodore von Karman from American National Biography

- Video recording of the N. Peters's lecture on life and work of Theodore von Kármán

- Theodore von Kármán at Find a Grave

- 1881 births

- 1963 deaths

- 20th-century American scientists

- Aerodynamicists

- ASME Medal recipients

- Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I

- Budapest University of Technology and Economics alumni

- California Institute of Technology faculty

- Early spaceflight scientists

- Fellows of the American Physical Society

- Fluid dynamicists

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- Hungarian aerospace engineers

- Hungarian emigrants to the United States

- 20th-century Hungarian physicists

- 20th-century Hungarian inventors

- Hungarian Jews

- Hungarian nobility

- Jewish American scientists

- Jewish inventors

- John Fritz Medal recipients

- Ludwig-Prandtl-Ring recipients

- Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Medal for Merit recipients

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Scientists from Budapest

- Royal Aeronautical Society Gold Medal winners

- RWTH Aachen University faculty

- 20th-century American inventors

- University of Göttingen alumni

- University of Göttingen faculty