Unabomber Manifesto

Industrial Society and Its Future, widely called the Unabomber Manifesto, is a 35,000 word essay by Ted Kaczynski contending that the Industrial Revolution began a harmful process of technology destroying nature, while forcing humans to adapt to machines, and creating a sociopolitical order that suppresses human freedom and potential. The manifesto formed the ideological foundation of Kaczynski's 1978–1995 mail bomb campaign, designed to protect wilderness by hastening the collapse of industrial society.

It was originally printed in 1995 in supplements to Washington Post and New York Times after Kaczynski offered to end his bombing campaign for national exposure. Attorney General Janet Reno authorized the printing to help the FBI identify the author. The printings and publicity around them eclipsed the bombings in notoriety, and led to Kaczynski's identification by his brother, David Kaczynski.

The manifesto argues against accepting individual technological advancements as purely positive without accounting for their overall effect, which includes the fall of small-scale living, and the rise of uninhabitable cities. While originally regarded as a thoughtful critique of modern society, with roots in the work of academic authors such as Jacques Ellul, Desmond Morris, and Martin Seligman,[1] Kaczynski's 1996 trial polarised public opinion around the essay, as his court-appointed lawyers tried to justify their insanity defense around characterizing the manifesto as the work of a madman, and the prosecution lawyers rested their case on it being produced by a lucid mind.

While Americans abhorred Kaczynski's violence, his manifesto expressed ideas that continue to be commonly shared among the American public.[2] A 2017 Rolling Stone article stated that Kaczynski was an early adopter of the concept that:

- "We give up a piece of ourselves whenever we adjust to conform to society's standards. That, and we're too plugged in. We're letting technology take over our lives, willingly."[3]

The Labadie Collection of the University of Michigan houses a copy of Industrial Society and its Future, which has been translated into French, remains on college reading lists, and was updated in Kaczynski's 2016 Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How, which defends his political philosophy in greater depth.

Background and publication[]

Between 1978 and 1995, Ted Kaczynski engaged in a mail bomb campaign[4] against people involved with modern technology.[citation needed] His targets were universities and airlines, which the FBI shortened as UNABOM. In June 1995, Kaczynski offered to end his campaign if one of several publications (the Washington Post, New York Times, or Penthouse) would publish his critique of technology, titled Industrial Society and Its Future, which became widely known as the "Unabomber Manifesto".[5]

Kaczynski believed that his violence, as direct action when words were insufficient, would draw others to pay attention to his critique.[6] He wanted his ideas to be taken seriously.[7] The media debated the ethics of publishing the manifesto under duress.[8][5] The United States Attorney General Janet Reno advocated for the essay to be shared such that a reader could recognize its author.[5]

During that summer, the FBI worked with literature scholars to compare the Unabomber's oeuvre against the works of Joseph Conrad, including The Secret Agent, based on their shared themes.[9][10]

The Washington Post published the manifesto in full within a supplement on September 19, 1995, splitting the cost with The New York Times. According to a statement, the Post had the "mechanical ability to distribute a separate section in all copies of its daily newspaper."[11][12] A Berkeley-based chess book publisher began publishing copies in paperback the next month without Kaczynski's consent.[13]

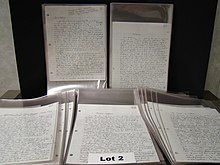

Kaczynski had drafted an essay of the ideas that would become the manifesto in 1971: that technological progress would extinguish individual liberty and that proselytizing libertarian philosophy would be insufficient without direct action.[7] The original, handwritten manifesto sold for $20,053 in a 2011 auction of Kaczynski's assets, along with typewritten editions and their typewriters, to raise restitution for his victims.[14][15]

Contents[]

At 35,000 words, Industrial Society and Its Future lays very detailed blame on technology for destroying human-scale communities.[5] Kaczynski contends that the Industrial Revolution harmed the human race by developing into a sociopolitical order that subjugates human needs beneath its own. This system, he wrote, destroys nature and suppresses individual freedom. In short, humans adapt to machines rather than vice versa, resulting in a society hostile to human potential.[7]

Kaczynski indicts technological progress with the destruction of small human communities and rise of uninhabitable cities controlled by an unaccountable state. He contends that this relentless technological progress will not dissipate on its own because individual technological advancements are seen as good despite the sum effects of this progress. Kaczynski describes modern society as defending this order against dissent, in which individuals are adjusted to fit the system and those outside it are seen as bad. This tendency, he says, gives rise to expansive police powers, mind-numbing mass media, and indiscriminate promotion of drugs.[7] He criticizes both big government and big business as the ineluctable result of industrialization,[5] and holds scientists and "technophiles" responsible for recklessly pursuing power through technological advancements.[7]

He argues that this industrialized system's collapse will be devastating and that quickening the collapse will mitigate the devastation's impact. He justifies the trade-offs that come with losing industrial society as being worth the cost.[7] Kaczynski's ideal revolution seeks not to overthrow government but the economic and technological foundation of modern society.[16] He seeks to destroy existing society and protect the wilderness, the antithesis of technology.[7]

Criticism[]

One scholar accused him of "collecting philosophical and environmental clichés to reinforce common American concerns".[5]

Influences[]

Industrial Society and Its Future echoed contemporary critics of technology and industrialization such as John Zerzan, Jacques Ellul,[17] Rachel Carson, Lewis Mumford, and E. F. Schumacher.[18] Its idea of the "disruption of the power process" similarly echoed social critics emphasizing the lack of meaningful work as a primary cause of social problems, including Mumford, Paul Goodman, and Eric Hoffer.[18] Aldous Huxley addressed its general theme in Brave New World, to which Kaczynski refers in his text. Kaczynski's ideas of "oversocialization" and "surrogate activities" recall Sigmund Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents and its theories of rationalization and sublimation (a term which Kaczynski uses three times to describe "surrogate activities").[19]

However, a 2021 study by Sean Fleming shows that many of these similarities are coincidental.[20] Kaczynski had not read Lewis Mumford, Paul Goodman, or John Zerzan until after he submitted Industrial Society and Its Future to the New York Times and the Washington Post. There is no evidence that he read Freud, Carson, or Schumacher. Instead, Fleming argues, Industrial Society and Its Future "is a synthesis of ideas from [...] French philosopher Jacques Ellul, British zoologist Desmond Morris, and American psychologist Martin Seligman."[20] Kaczynski's understanding of technology, his idea of maladaptation, and his critique of leftism are largely derived from Ellul's 1954 book, The Technological Society. Kaczynski's concept of “surrogate activities” comes from Desmond Morris's concept of “survival-substitute activities,” while his concept of “the power process” combines Morris's concept of “the Stimulus Struggle” with Seligman's concept of learned helplessness. Fleming's study relies on archival material from the Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan, including a "secret" set of footnotes that Kaczynski did not include in the Washington Post version of Industrial Society and Its Future.[20]

Aftermath[]

Kaczynski had intended for his mail bombing campaign to raise awareness for the message in Industrial Society and Its Future, which he wanted to be seriously regarded.[7] With its initial publication in 1995, the manifesto was received as intellectually deep and sane. Writers described the manifesto's sentiment as familiar.

To Kirkpatrick Sale, the Unabomber was "a rational man" with reasonable beliefs about technology. He recommended the manifesto's opening sentence for the forefront of American politics. Cynthia Ozick likened the work to an American Raskolnikov (of Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment), as a "philosophical criminal of exceptional intelligence and humanitarian purpose ... driven to commit murder out of an uncompromising idealism".[7] Numerous websites engaging with the manifesto's message appeared online.[7]

While Kaczynski's effort to publish his manifesto, more so than the bombings themselves, brought him into the American news,[21] and the manifesto was widely spread via newspapers, book reprints, and the Internet, ultimately, the ideas in the manifesto were eclipsed by reaction to the violence of the bombings, and did not spark the serious public consideration he was looking for.[21][22]

Reading the manifesto, David Kaczynski suspected his brother's authorship and notified the FBI.[7]

Effect of the trial[]

After Ted Kaczynski's April 1996 arrest, he wanted to use the trial to disseminate his views,[5] but the judge denied him permission to represent himself. Instead, his court-appointed lawyers planned an insanity defense that would discredit Industrial Society and Its Future against his will. The prosecution's psychiatrists counter-cited the manifesto as evidence of the Unabomber's lucidity, and Kaczynski's sanity was tried in court and in the media. Kaczynski responded by taking a plea bargain for life imprisonment without parole in May 1998.

Kaczynski's biographer argued that the public should look beyond this "genius-or-madman debate", and view the manifesto as reflecting normal, common, unexceptional ideas shared by Americans, sharing their distrust over the direction of civilization. While most Americans abhorred his violence, adherents to his anti-technology message have celebrated his call to question technology and preserve wilderness.[7] From his Colorado jail,[7] he continues to clarify his philosophy with other writers by letter.[5]

Legacy[]

As of 2000, Industrial Society and Its Future remained on college reading lists and the green anarchist and eco-extremist movements came to hold Kaczynski's writing in high regard, with the manifesto finding a niche audience among critics of technology, such as the speculative science fiction and anarcho-primitivist communities.[23] [7][24] It has since been translated into French by Jean-Marie Apostolidès.[25]

Since 2000, the Labadie Collection houses a copy of the manifesto along with the Unabomber's others writings, letters and papers after he officially designated the University of Michigan to receive them. They have since become one of the most popular archives in their Special collections.[26]

In 2017, an article in Rolling Stone stated that Kaczynski was an early adopter of the idea that:

- "We give up a piece of ourselves whenever we adjust to conform to society's standards. That, and we're too plugged in. We're letting technology take over our lives, willingly."[3]

In 2018, New York magazine stated that the manifesto generated later interest from neoconservatives, environmentalists, and anarcho-primitivists.[27]

In December 2020, a man who was arrested at Charleston International Airport on a charge of "conveying false information regarding attempted use of a destructive device," after he falsely threatened that he had a bomb was found to have carried the Unabomber manifesto.[28][29]

Reprints and further work[]

Feral House republished the manifesto in Kaczynski's first book, the 2010 Technological Slavery, alongside correspondence and an interview.[30][31] Kaczynski was unsatisfied with the book and his lack of control in its publication.[32] Kaczynski's 2016 Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How updates his 1995 manifesto with more relevant references and defends his political philosophy in greater depth.[32][33]

See also[]

- Accelerationism

- Anarchism and violence

- Anarcho-primitivism

- Criticism of technology

- Eco-terrorism

- Green anarchism

- Neo-Luddism

- Propaganda of the deed

References[]

- ^ Fleming, Sean (May 7, 2021). "The Unabomber and the origins of anti-tech radicalism". Journal of Political Ideologies: 1–19. doi:10.1080/13569317.2021.1921940. ISSN 1356-9317.

- ^ Kelman 2017, p. fn4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Diamond, Jason (August 17, 2017). "Flashback: Unabomber Publishes His 'Manifesto'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Michael 2012, p. 75.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Michael 2012, p. 76.

- ^ Simmons 1999, p. 688.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Chase 2000.

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph (September 21, 2015). "Defying critics to publish the Unabomber 'Manifesto'". Poynter. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Kovaleski 1996.

- ^ Kelman 2017, p. 186.

- ^ Graham, Donald E.; Sulzberger Jr., Arthur O. (September 19, 1995). "Statement by Papers' Publishers". The Washington Post. p. A07. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Post, Times publish Unabomber manifesto". CNN. September 19, 1995. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Unabomber Manifesto Published in Paperback; 3,000 Copies Sold". Los Angeles Daily News. Associated Press. October 14, 1995. p. 10. ProQuest 281557917.

- ^ "Unabomber auction nets $190,000". NBC News. Associated Press. June 2, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "Feds to auction Unabomber's manifesto". NBC News. May 13, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Kelman 2017, p. fn1.

- ^ Kaczynski, Ted. "Progress vs. Liberty (aka '1971 Essay')". Wild Will Project. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sale, Kirkpatrick (September 25, 1995). "Unabomber's Secret Treatise". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ Wright, Robert (August 28, 1995). "The Evolution of Despair". Time. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Fleming 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Simmons 1999, p. 675.

- ^ Richardson, Chris (2020). Violence in American Society: An Encyclopedia of Trends, Problems, and Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 502. ISBN 978-1-4408-5468-2.

- ^ Tan & Snow 2015, p. 521.

- ^ John H. Richardson (December 11, 2018). "Children of Ted Two decades after his last deadly act of ecoterrorism, the Unabomber has become an unlikely prophet to a new generation of acolytes". NYMAG. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Hawkins, Kayla (August 1, 2017). "What Is The Unabomber Manifesto? The Document Helped End The 'Manhunt' For Ted Kaczynski". Bustle. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Jeffrey R. Young (May 20, 2012). "The Unabomber's Pen Pal". www.chronicle.com. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Richardson, John H. (December 11, 2018). "The Unlikely New Generation of Unabomber Acolytes". Intelligencer. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Man charged in airport bomb scare had razor blade in his shoe, Unabomber manifesto". WCBD News 2. December 9, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Fortier-Bensen, Tony (December 8, 2020). "Affidavits shed new light on airport bomb scare in November, man had Unabomber's manifesto". WCIV. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Kellogg, Carolyn (May 19, 2011). "Possible Tylenol-poisoning suspect Ted Kaczynski and his anti-technology manifesto". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Adams, Guy (October 22, 2011). "Unabomber aims for best-seller with green book". The Independent. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moen 2019, p. 223.

- ^ Bailey, Holly (January 27, 2016). "The Unabomber takes on the Internet". Yahoo News. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Chase, Alston (June 2000). "Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber". The Atlantic. ISSN 1072-7825.

- Kelman, David (2020). "Politics in a Small Room: Subterranean Babel in Piglia's El camino de Ida". The Yearbook of Comparative Literature. 63 (1): 179–201. doi:10.3138/ycl.63.005. ISSN 1947-2978. S2CID 220494877. Project MUSE 758028.

- Kovaleski, Serge F. (July 9, 1996). "1907 Conrad Novel May Have Inspired Unabomb Suspect". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286.

- McHugh, Paul (November 2003). "The making of a killer". First Things: A Monthly Journal of Religion and Public Life (137): 58+. ISSN 1047-5141. Gale A110263474.

- Michael, George (2012). "Ecoextremism and the Radical Animal Liberation Movement". Lone Wolf Terror and the Rise of Leaderless Resistance. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 61–78. ISBN 978-0-8265-1857-6.

- Moen, Ole Martin (February 2019). "The Unabomber's ethics". Bioethics. 33 (2): 223–229. doi:10.1111/bioe.12494. hdl:10852/76721. ISSN 0269-9702. PMID 30136739. EBSCOhost 134360154.

- Richardson, John H. (December 11, 2018). "The Unlikely New Generation of Unabomber Acolytes". New York Magazine. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Simmons, Ryan (1999). "What is a Terrorist? Contemporary Authorship, the Unabomber, and Mao II". MFS Modern Fiction Studies. 45 (3): 675–695. doi:10.1353/mfs.1999.0056. ISSN 1080-658X. S2CID 162235453. Project MUSE 21412.

- Tan, Anna E.; Snow, David (November 2015). "Cultural Conflicts and Social Movements". In della Porta, Donatella; Diani, Mario (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements. pp. 513–533. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199678402.013.5. ISBN 9780199678402.

Further reading[]

- Chase, Alston (2004). A Mind for Murder: The Education of the Unabomber and the Origins of Modern Terrorism. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32556-0.

- Didion, Joan (April 23, 1998). "Varieties of Madness". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504.

- Finnegan, William (May 20, 2011). "The Unabomber Returns". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X.

- Hough, Andrew (July 24, 2011). "Norway shooting: Anders Behring Breivik plagiarised 'Unabomber'". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235.

- Katz, Jon (April 17, 1998). "The Unabomber's Legacy, Part I". Wired. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Kravets, David (September 20, 2015). "Unabomber's anti-technology manifesto published 20 years ago". Ars Technica. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Rubin, Mike (June 4, 1996). "An explosive bestseller". Village Voice. 41 (23): 8. ISSN 0042-6180. EBSCOhost 9606174925.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick (September 25, 1995). "Unabomber's Secret Treatise: Is There Method in His Madness?". The Nation.

- Sikorski, Wade (1997). "On Mad Bombers". Theory & Event. 1 (1). doi:10.1353/tae.1991.0012. ISSN 1092-311X. S2CID 144440330. Project MUSE 32449.

External links[]

- Full manifesto from the Washington Post

- 1995 essays

- Anarchist manifestos

- Eco-terrorism

- Technophobia