Ted Kaczynski

Ted Kaczynski | |

|---|---|

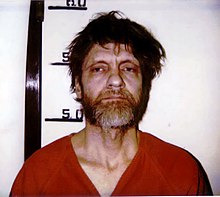

Kaczynski after his capture in 1996 | |

| Born | Theodore John Kaczynski May 22, 1942 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Other names | Unabomber, FC |

| Occupation | Mathematics professor |

Notable work | Industrial Society and Its Future (1995) |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated at USP Florence ADMAX, #04475-046[1] |

| Relatives | David Kaczynski (brother) |

| Conviction(s) | 10 counts of transportation, mailing, and use of bombs; three counts of murder |

| Criminal penalty | 8 consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole |

| Details | |

Span of crimes | 1978–1995 |

| Killed | 3 |

| Injured | 23 |

Date apprehended | April 3, 1996[2] |

| Education |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Complex analysis |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley |

| Thesis | Boundary Functions (1967) |

| Doctoral advisor | Allen Shields |

Theodore John Kaczynski (/kəˈzɪnski/ kə-ZIN-skee; born May 22, 1942), also known as the Unabomber (/ˈjuːnəbɒmər/), is an American domestic terrorist and former mathematics professor.[3][4] He was a mathematics prodigy, but abandoned his academic career in 1969 to pursue a primitive life.[5] Between 1978 and 1995, he killed three people and injured 23 others in a nationwide bombing campaign against people he believed to be advancing modern technology and the destruction of the environment. He issued a social critique opposing industrialization and advocating a nature-centered form of anarchism.[6]

In 1971, Kaczynski moved to a remote cabin without electricity or running water near Lincoln, Montana, where he lived as a recluse while learning survival skills to become self-sufficient. He witnessed the destruction of the wilderness surrounding his cabin and concluded that living in nature was becoming impossible, resolving to fight industrialization and its destruction of nature. He used terrorism to fight this industrialization, beginning his bombing campaign in 1978. In 1995, he sent a letter to The New York Times and promised to "desist from terrorism" if the Times or The Washington Post published his essay Industrial Society and Its Future, in which he argued that his bombings were extreme but necessary to attract attention to the erosion of human freedom and dignity by modern technologies that require mass organization.[7]

Kaczynski was the subject of the longest and most expensive investigation in the history of the Federal Bureau of Investigation up to that point.[8] The FBI used the case identifier UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) to refer to his case before his identity was known, which resulted in the media naming him the "Unabomber". The FBI and Attorney General Janet Reno pushed for the publication of Industrial Society and Its Future, which appeared in The Washington Post in September 1995. Upon reading the essay, Kaczynski's brother David recognized the prose style and reported his suspicions to the FBI. After his arrest in 1996, Kaczynski—maintaining that he was sane—tried and failed to dismiss his court-appointed lawyers because they wanted him to plead insanity to avoid the death penalty. In 1998, a plea bargain was reached under which he pleaded guilty to all charges and was sentenced to eight consecutive life terms in prison without the possibility of parole.

Early life[]

Childhood[]

Theodore John Kaczynski was born on May 22, 1942, in Chicago, Illinois, to working-class parents, Wanda Theresa (née Dombek) and Theodore Richard Kaczynski, a sausage maker.[9] The two were Polish Americans, and were raised as Catholics but later became atheists.[10] They married on April 11, 1939.[10]

Kaczynski's parents told his younger brother, David, that Ted had been a happy baby until severe hives forced him into hospital isolation with limited contact with others, after which he "showed little emotions for months".[10] Wanda recalled Ted recoiling from a picture of himself as an infant being held down by physicians examining his hives. She said he showed sympathy for animals who were in cages or otherwise helpless, which she speculated stemmed from his experience in hospital isolation.[11]

From first to fourth grade (ages six to nine), Kaczynski attended Sherman Elementary School in Chicago, where administrators described him as healthy and well-adjusted.[12] In 1952, three years after David was born, the family moved to suburban Evergreen Park, Illinois; Ted transferred to Evergreen Park Central Junior High School. After testing scored his IQ at 167,[13] he skipped the sixth grade. Kaczynski later described this as a pivotal event: previously he had socialized with his peers and was even a leader, but after skipping ahead of them he felt he did not fit in with the older children, who bullied him.[14]

Neighbors in Evergreen Park later described the Kaczynski family as "civic-minded folks", one recalling the parents "sacrificed everything they had for their children".[10] Both Ted and David were intelligent, but Ted exceptionally so. Neighbors described him as a smart but lonely individual.[10][15] His mother recalled Ted as a shy child who would become unresponsive if pressured into a social situation.[16] At one point she was so worried about his social development that she considered entering him in a study for autistic children led by Bruno Bettelheim. She decided against it after seeing Bettelheim's abrupt and cold manner.[17]

High school[]

Kaczynski attended Evergreen Park Community High School, where he excelled academically. He played the trombone in the marching band and was a member of the mathematics, biology, coin, and German clubs.[18][19] In 1996, a former classmate said: "He was never really seen as a person, as an individual personality ... He was always regarded as a walking brain, so to speak."[10] During this period, Kaczynski became intensely interested in mathematics, spending hours studying and solving advanced problems. He became associated with a group of like-minded boys interested in science and mathematics, known as the "briefcase boys" for their penchant for carrying briefcases.[19]

Throughout high school, Kaczynski was ahead of his classmates academically. Placed in a more advanced mathematics class, he soon mastered the material. He skipped the eleventh grade, and by attending summer school he graduated at age 15. Kaczynski was one of his school's five National Merit finalists and was encouraged to apply to Harvard College.[18] He entered Harvard on a scholarship in 1958 at age 16.[20] A classmate later said Kaczynski was emotionally unprepared: "They packed him up and sent him to Harvard before he was ready ... He didn't even have a driver's license."[10]

Harvard College[]

During his first year at Harvard, Kaczynski lived at 8 Prescott Street, which was designed to accommodate the youngest, most precocious incoming students in a small, intimate living space. For the following three years, he lived at Eliot House. Housemates and other students at Harvard described Kaczynski as a very intelligent but socially reserved person.[21] Kaczynski earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in mathematics from Harvard in 1962, finishing with a GPA of 3.12.[22][23][24]

Psychological study[]

In his second year at Harvard, Kaczynski participated in a study described by author Alston Chase as a "purposely brutalizing psychological experiment" led by Harvard psychologist Henry Murray. Subjects were told they would debate personal philosophy with a fellow student and were asked to write essays detailing their personal beliefs and aspirations. The essays were turned over to an anonymous individual who would confront and belittle the subject in what Murray himself called "vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive" attacks, using the content of the essays as ammunition.[25] Electrodes monitored the subject's physiological reactions. These encounters were filmed, and subjects' expressions of anger and rage were later played back to them repeatedly.[25] The experiment lasted three years, with someone verbally abusing and humiliating Kaczynski each week.[26][27] Kaczynski spent 200 hours as part of the study.[28]

Kaczynski's lawyers later attributed his hostility towards mind control techniques to his participation in Murray's study.[25] Some sources have suggested that Murray's experiments were part of Project MKUltra, the Central Intelligence Agency's research into mind control.[29][30] Chase and others have also suggested that this experience may have motivated Kaczynski's criminal activities.[31][32] Kaczynski stated he resented Murray and his co-workers, primarily because of the invasion of his privacy he perceived as a result of their experiments. Nevertheless, he said he was "quite confident that my experiences with Professor Murray had no significant effect on the course of my life".[33]

Mathematics career[]

In 1962, Kaczynski enrolled at the University of Michigan, where he earned his master's and doctoral degrees in mathematics in 1964 and 1967, respectively. Michigan was not his first choice for postgraduate education; he had applied to the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Chicago, both of which accepted him but offered him no teaching position or financial aid. Michigan offered him an annual grant of $2,310 (equivalent to $19,763 in 2020) and a teaching post.[24]

At Michigan, Kaczynski specialized in complex analysis, specifically geometric function theory. Professor Peter Duren said of Kaczynski, "He was an unusual person. He was not like the other graduate students. He was much more focused about his work. He had a drive to discover mathematical truth." George Piranian, another of his Michigan mathematics professors, said, "It is not enough to say he was smart".[34] Kaczynski received 1 F, 5 Bs and 12 As in his 18 courses at the university. In 2006, he said he had unpleasant memories of Michigan and felt the university had low standards for grading, as evidenced by his relatively high grades.[24]

For a period of several weeks in 1966, Kaczynski experienced intense sexual fantasies of being a female and decided to undergo gender transition. He arranged to meet with a psychiatrist, but changed his mind in the waiting room and did not disclose his reason for making the appointment. Afterwards, enraged, he considered killing the psychiatrist and other people whom he hated. Kaczynski described this episode as a "major turning point" in his life:[35][36][37] "I felt disgusted about what my uncontrolled sexual cravings had almost led me to do. And I felt humiliated, and I violently hated the psychiatrist. Just then there came a major turning point in my life. Like a Phoenix, I burst from the ashes of my despair to a glorious new hope."[36]

In 1967, Kaczynski's dissertation Boundary Functions[38] won the Sumner B. Myers Prize for Michigan's best mathematics dissertation of the year.[10] Allen Shields, his doctoral advisor, called it "the best I have ever directed",[24] and Maxwell Reade, a member of his dissertation committee, said, "I would guess that maybe 10 or 12 men in the country understood or appreciated it."[10][34]

In late 1967, the 25-year-old Kaczynski became an acting assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught mathematics. By September 1968, Kaczynski was appointed assistant professor, a sign that he was on track for tenure.[10] His teaching evaluations suggest he was not well-liked by his students: he seemed uncomfortable teaching, taught straight from the textbook and refused to answer questions.[10] Without any explanation, Kaczynski resigned on June 30, 1969.[38] The chairman of the mathematics department, J. W. Addison, called this a "sudden and unexpected" resignation.[39][40]

In 1996, reporters for the Los Angeles Times interviewed mathematicians about Kaczynski's work and concluded that Kaczynski's subfield effectively ceased to exist after the 1960s as most of its conjectures were proven. According to mathematician Donald Rung, if Kaczynski continued to work in mathematics he "probably would have gone on to some other area".[38]

Life in Montana[]

After resigning from Berkeley, Kaczynski moved to his parents' home in Lombard, Illinois. Two years later, in 1971, he moved to a remote cabin he had built outside Lincoln, Montana, where he could live a simple life with little money and without electricity or running water,[41] working odd jobs and receiving significant financial support from his family.[10]

His original goal was to become self-sufficient so he could live autonomously. He used an old bicycle to get to town, and a volunteer at the local library said he visited frequently to read classic works in their original languages. Other Lincoln residents said later that such a lifestyle was not unusual in the area.[42] Kaczynski's cabin was described by a census taker in the 1990 census as containing a bed, two chairs, storage trunks, a gas stove, and lots of books.[18]

Starting in 1975, Kaczynski performed acts of sabotage including arson and booby trapping against developments near to his cabin.[43] He also dedicated himself to reading about sociology and political philosophy, including the works of Jacques Ellul.[25] Kaczynski's brother David later stated that Ellul's book The Technological Society "became Ted's Bible".[44] Kaczynski recounted in 1998, "When I read the book for the first time, I was delighted, because I thought, 'Here is someone who is saying what I have already been thinking.'"[25]

In an interview after his arrest, he recalled being shocked on a hike to one of his favorite wild spots:[45]

It's kind of rolling country, not flat, and when you get to the edge of it you find these ravines that cut very steeply in to cliff-like drop-offs and there was even a waterfall there. It was about a two days' hike from my cabin. That was the best spot until the summer of 1983. That summer there were too many people around my cabin so I decided I needed some peace. I went back to the plateau and when I got there I found they had put a road right through the middle of it ... You just can't imagine how upset I was. It was from that point on I decided that, rather than trying to acquire further wilderness skills, I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge.

Kaczynski was visited multiple times in Montana by his father, who was impressed by Ted's wilderness skills. Kaczynski's father was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer in 1990 and held a family meeting without Kaczynski later that year to map out their future.[18] In October 1990, Kaczynski's father committed suicide.[46]

Bombings[]

Between 1978 and 1995, Kaczynski mailed or hand-delivered a series of increasingly sophisticated bombs that cumulatively killed three people and injured 23 others. Sixteen bombs were attributed to Kaczynski. While the bombing devices varied widely through the years, many contained the initials "FC", which Kaczynski later said stood for "Freedom Club",[47] inscribed on parts inside. He purposely left misleading clues in the devices and took extreme care in preparing them to avoid leaving fingerprints; fingerprints found on some of the devices did not match those found on letters attributed to Kaczynski.[48][a]

Initial bombings[]

Kaczynski's first mail bomb was directed at Buckley Crist, a professor of materials engineering at Northwestern University. On May 25, 1978, a package bearing Crist's return address was found in a parking lot at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The package was "returned" to Crist, who was suspicious because he had not sent it, so he contacted campus police. Officer Terry Marker opened the package, which exploded and caused minor injuries.[49] Kaczynski had returned to Chicago for the May 1978 bombing and stayed there for a time to work with his father and brother at a foam rubber factory. In August 1978, his brother fired him for writing insulting limericks about a female supervisor Ted had courted briefly.[50][51] The supervisor later recalled Kaczynski as intelligent and quiet, but remembered little of their acquaintanceship and firmly denied they had had any romantic relationship.[52] Kaczynski's second bomb was sent nearly one year after the first one, again to Northwestern University. The bomb, concealed inside a cigar box and left on a table, caused minor injuries to graduate student John Harris when he opened it.[49]

FBI involvement[]

In 1979, a bomb was placed in the cargo hold of American Airlines Flight 444, a Boeing 727 flying from Chicago to Washington, D.C. A faulty timing mechanism prevented the bomb from exploding, but it released smoke, which caused the pilots to carry out an emergency landing. Authorities said it had enough power to "obliterate the plane" had it exploded.[49] Kaczynski sent his next bomb to Percy Wood, the president of United Airlines.[53]

Kaczynski left false clues in most bombs, which he intentionally made hard to find to make them appear more legitimate. Clues included metal plates stamped with the initials "FC" hidden somewhere (usually in the pipe end cap) in bombs, a note left in a bomb that did not detonate reading "Wu—It works! I told you it would—RV," and the Eugene O'Neill one dollar stamps often used to send his boxes.[48][54][55] He sent one bomb embedded in a copy of Sloan Wilson's novel Ice Brothers.[49] The FBI theorized that Kaczynski's crimes involved a theme of nature, trees and wood. He often included bits of a tree branch and bark in his bombs. His selected targets included Percy Wood and Professor Leroy Wood. Crime writer Robert Graysmith noted his "obsession with wood" was "a large factor" in the bombings.[56]

Later bombings[]

In 1981, a package that had been discovered in a hallway at the University of Utah was brought to the campus police, and was defused by a bomb squad.[49] In May of the following year, a bomb was sent to Patrick C. Fischer, a professor teaching at Vanderbilt University. Fischer was on vacation in Puerto Rico at the time and his secretary, Janet Smith, opened the bomb and received injuries to the face and arms.[49][57]

Kaczynski's next two bombs targeted people at the University of California, Berkeley. The first, in July 1982, caused serious injuries to engineering professor Diogenes Angelakos.[49] Nearly three years later, in May 1985, John Hauser, a graduate student and captain in the United States Air Force, lost four fingers and vision in one eye.[58] Kaczynski handcrafted the bomb from wooden parts.[59] A bomb sent to the Boeing Company in Auburn, Washington, was defused by a bomb squad the following month.[58] In November 1985, professor James V. McConnell and research assistant Nicklaus Suino were both severely injured after Suino opened a mail bomb addressed to McConnell.[58]

In late 1985, a nail-and-splinter-loaded bomb placed in the parking lot of his store in Sacramento, California, killed 38-year-old computer store owner Hugh Scrutton. A similar attack against a computer store took place in Salt Lake City, Utah, on February 20, 1987. The bomb, disguised as a piece of lumber, injured Gary Wright when he attempted to remove it from the store's parking lot. The explosion severed nerves in Wright's left arm and propelled over 200 pieces of shrapnel into his body.[b] Kaczynski was spotted while planting the Salt Lake City bomb. This led to a widely distributed sketch of the suspect as a hooded man with a mustache and aviator sunglasses.[61][62]

In 1993, after a six-year break, Kaczynski mailed a bomb to the home of Charles Epstein from the University of California, San Francisco. Epstein lost several fingers upon opening the package. In the same weekend, Kaczynski mailed a bomb to David Gelernter, a computer science professor at Yale University. Gelernter lost sight in one eye, hearing in one ear, and a portion of his right hand.[63]

In 1994, Burson-Marsteller executive Thomas Mosser was killed after opening a mail bomb sent to his home in New Jersey. In a letter to The New York Times, Kaczynski wrote he had sent the bomb because of Mosser's work repairing the public image of Exxon after the Exxon Valdez oil spill.[64] This was followed by the 1995 murder of Gilbert Brent Murray, president of the timber industry lobbying group California Forestry Association, by a mail bomb addressed to previous president William Dennison, who had retired. Geneticist Phillip Sharp at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology received a threatening letter shortly afterwards.[63]

Table of bombings[]

| Date | State | Location | Explosion | Victim(s) | Occupation of victim(s) | Injuries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 25, 1978 | Illinois | Northwestern University | Yes | Terry Marker | University police officer | Minor cuts and burns | |

| May 9, 1979 | Yes | John Harris | Graduate student | Minor cuts and burns | |||

| November 15, 1979 | American Airlines Flight 444 from Chicago to Washington, D.C. (explosion occurred midflight) | Yes | Twelve passengers | Multiple | Non-lethal smoke inhalation | ||

| June 10, 1980 | Lake Forest | Yes | Percy Wood | President of United Airlines | Severe cuts and burns over most of body and face | ||

| October 8, 1981 | Utah | University of Utah | Bomb defused | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| May 5, 1982 | Tennessee | Vanderbilt University | Yes | Janet Smith | University secretary | Severe burns to hands; shrapnel wounds to body | |

| July 2, 1982 | California | University of California, Berkeley | Yes | Diogenes Angelakos | Engineering professor | Severe burns and shrapnel wounds to hand and face | |

| May 15, 1985 | Yes | John Hauser | Graduate student | Loss of four fingers and severed artery in right arm; partial loss of vision in left eye | |||

| June 13, 1985 | Washington | The Boeing Company in Auburn | Bomb defused | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| November 15, 1985 | Michigan | University of Michigan | Yes | James V. McConnell | Psychology professor | Temporary hearing loss | |

| Yes | Nicklaus Suino | Research assistant | Burns and shrapnel wounds | ||||

| December 11, 1985 | California | Sacramento | Yes | Hugh Scrutton | Computer store owner | Death | |

| February 20, 1987 | Utah | Salt Lake City | Yes | Gary Wright | Computer store owner | Severe nerve damage to left arm | |

| June 22, 1993 | California | Tiburon | Yes | Charles Epstein | Geneticist | Severe damage to both eardrums with partial hearing loss, loss of three fingers | |

| June 24, 1993 | Connecticut | Yale University | Yes | David Gelernter | Computer science professor | Severe burns and shrapnel wounds, damage to right eye, loss of right hand | |

| December 10, 1994 | New Jersey | North Caldwell | Yes | Thomas J. Mosser | Advertising executive at Burson-Marsteller | Death | |

| April 24, 1995 | California | Sacramento | Yes | Gilbert Brent Murray | Timber industry lobbyist | Death | |

| References:[65][66] | |||||||

Manifesto[]

In 1995, Kaczynski mailed several letters to media outlets outlining his goals and demanding a major newspaper print his 35,000-word essay Industrial Society and Its Future (dubbed the "Unabomber manifesto" by the FBI) verbatim.[67][68] He stated he would "desist from terrorism" if this demand was met.[7][69][70] There was controversy as to whether the essay should be published, but Attorney General Janet Reno and FBI Director Louis Freeh recommended its publication out of concern for public safety and in the hope that a reader could identify the author. Bob Guccione of Penthouse volunteered to publish it. Kaczynski replied Penthouse was less "respectable" than The New York Times and The Washington Post, and said that, "to increase our chances of getting our stuff published in some 'respectable' periodical", he would "reserve the right to plant one (and only one) bomb intended to kill, after our manuscript has been published" if Penthouse published the document instead of The Times or The Post.[71] The Washington Post published the essay on September 19, 1995.[72][73]

Kaczynski used a typewriter to write his manuscript, capitalizing entire words for emphasis in lieu of italics. He always referred to himself as either "we" or "FC" ("Freedom Club"), though there is no evidence that he worked with others. Donald Wayne Foster analyzed the writing at the request of Kaczynski's defense team in 1996 and noted that it contained irregular spelling and hyphenation, along with other linguistic idiosyncrasies. This led him to conclude that Kaczynski was its author.[74]

Summary[]

Industrial Society and Its Future begins with Kaczynski's assertion: "The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race."[75][76] He writes that technology has had a destabilizing effect on society, has made life unfulfilling, and has caused widespread psychological suffering.[77] Kaczynski argues that most people spend their time engaged in useless pursuits because of technological advances; he calls these "surrogate activities" wherein people strive toward artificial goals, including scientific work, consumption of entertainment, political activism and following sports teams.[77] He predicts that further technological advances will lead to extensive human genetic engineering and that human beings will be adjusted to meet the needs of the social systems, rather than vice versa.[77] Kaczynski states that technological progress can be stopped, in contrast to the viewpoint of people who he says understand technology's negative effects yet passively accept it as inevitable.[78] He calls for a return to primitivist lifestyles.[77] Kaczynski's critiques of civilization bear some similarities to anarcho-primitivism, but he rejected and criticized anarcho-primitivist views.[79][80][81]

Kaczynski argues that the erosion of human freedom is a natural product of an industrial society because "the system has to regulate human behavior closely in order to function", and that reform of the system is impossible as drastic changes to it would not be implemented because of their disruption of the system.[82] He states that the system has not yet fully achieved control over all human behavior and is in the midst of a struggle to gain that control. Kaczynski predicts that the system will break down if it cannot achieve significant control, and that it is likely this issue will be decided within the next 40 to 100 years.[82] He states that the task of those who oppose industrial society is to promote stress within and upon the society and to propagate anti-technology ideology, one that offers the "counter-ideal" of nature. Kaczynski goes on to say that a revolution will only be possible when industrial society is sufficiently unstable.[83]

A significant portion of the document is dedicated to discussing left-wing politics, Kaczynski attributing many of society's issues to leftists.[82] He defines leftists as "mainly socialists, collectivists, 'politically correct' types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists and the like".[84] He believes that oversocialization and feelings of inferiority primarily drive leftism,[77] and derides it as "one of the most widespread manifestations of the craziness of our world".[84] Kaczynski adds that the type of movement he envisions must be anti-leftist and refrain from collaboration with leftists, as in his view "leftism is in the long run inconsistent with wild nature, with human freedom and with the elimination of modern technology".[75] He also criticizes conservatives, describing them as fools who "whine about the decay of traditional values, yet ... enthusiastically support technological progress and economic growth".[84]

Contemporary Reception[]

James Q. Wilson, in a 1998 New York Times Op-Ed, “If it is the work of a madman, then the writings of many political philosophers—Jean Jacques Rousseau, Tom Paine, Karl Marx—are scarcely more sane.”[85]

"The Unabomber does not like socialization, technology, leftist political causes or conservative attitudes. Apart from his call for an (unspecified) revolution, his paper resembles something that a very good graduate student might have written."[86]

A fellow alumni of Harvard University in 2000 for The Atlantic wrote that "It is true that many believed Kaczynski was insane because they needed to believe it. But the truly disturbing aspect of Kaczynski and his ideas is not that they are so foreign but that they are so familiar." He argued that "We need to see Kaczynski as exceptional—madman or genius—because the alternative is so much more frightening."[87]

Other works[]

University of Michigan–Dearborn philosophy professor David Skrbina helped to compile Kaczynski's work into the 2010 anthology Technological Slavery, including the original manifesto, letters between Skrbina and Kaczynski, and other essays.[88] Kaczynski updated his 1995 manifesto as Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How to address advances in computers and the internet. He advocates practicing other types of protest and makes no mention of violence.[89]

According to a 2021 study, Kaczynski's manifesto "is a synthesis of ideas from three well known academics: French philosopher Jacques Ellul, British zoologist Desmond Morris, and American psychologist Martin Seligman."[90]

Investigation[]

Because of the material used to make the mail bombs, U.S. postal inspectors, who initially had responsibility for the case, labeled the suspect the "Junkyard Bomber".[91] FBI Inspector Terry D. Turchie was appointed to run the UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) investigation.[92] In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included 125 agents from the FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service was formed.[92] The task force grew to more than 150 full-time personnel, but minute analysis of recovered components of the bombs and the investigation into the lives of the victims proved of little use in identifying the suspect, who built the bombs primarily from scrap materials available almost anywhere. Investigators later learned that the victims were chosen indiscriminately from library research.[93]

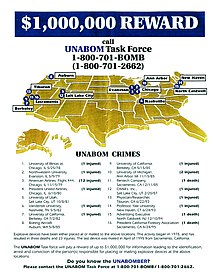

In 1980, chief agent John Douglas, working with agents in the FBI's Behavioral Sciences Unit, issued a psychological profile of the unidentified bomber. It described the offender as a man with above-average intelligence and connections to academia. This profile was later refined to characterize the offender as a neo-Luddite holding an academic degree in the hard sciences, but this psychologically based profile was discarded in 1983. FBI analysts developed an alternative theory that concentrated on the physical evidence in recovered bomb fragments. In this rival profile, the suspect was characterized as a blue-collar airplane mechanic.[94] The UNABOMB Task Force set up a toll-free telephone hotline to take calls related to the investigation, with a $1 million reward for anyone who could provide information leading to the Unabomber's capture.[95]

Before the publication of Industrial Society and Its Future, Kaczynski's brother, David, was encouraged by his wife to follow up on suspicions that Ted was the Unabomber.[96] David was dismissive at first, but he took the likelihood more seriously after reading the manifesto a week after it was published in September 1995. He searched through old family papers and found letters dating to the 1970s that Ted had sent to newspapers to protest the abuses of technology using phrasing similar to that in the manifesto.[97]

Before the manifesto's publication, the FBI held many press conferences asking the public to help identify the Unabomber. They were convinced that the bomber was from the Chicago area where he began his bombings, had worked in or had some connection to Salt Lake City, and by the 1990s had some association with the San Francisco Bay Area. This geographical information and the wording in excerpts from the manifesto that were released before the entire text of the manifesto was published persuaded David's wife to urge him to read it.[98][99]

After publication[]

After the manifesto was published, the FBI received thousands of leads in response to its offer of a reward for information leading to the identification of the Unabomber.[99] While the FBI reviewed new leads, Kaczynski's brother David hired private investigator Susan Swanson in Chicago to investigate Ted's activities discreetly.[100] David later hired Washington, D.C. attorney Tony Bisceglie to organize the evidence acquired by Swanson and contact the FBI, given the presumed difficulty of attracting the FBI's attention. Kaczynski's family wanted to protect him from the danger of an FBI raid, such as those at Ruby Ridge or Waco, since they feared a violent outcome from any attempt by the FBI to contact Kaczynski.[101][102]

In early 1996, an investigator working with Bisceglie contacted former FBI hostage negotiator and criminal profiler Clinton R. Van Zandt. Bisceglie asked him to compare the manifesto to typewritten copies of handwritten letters David had received from his brother. Van Zandt's initial analysis determined that there was better than a 60 percent chance that the same person had written the manifesto, which had been in public circulation for half a year. Van Zandt's second analytical team determined a higher likelihood. He recommended Bisceglie's client contact the FBI immediately.[101]

In February 1996, Bisceglie gave a copy of the 1971 essay written by Ted Kaczynski to Molly Flynn at the FBI.[92] She forwarded the essay to the San Francisco-based task force. FBI profiler James R. Fitzgerald[103][104] recognized similarities in the writings using linguistic analysis and determined that the author of the essays and the manifesto was almost certainly the same person. Combined with facts gleaned from the bombings and Kaczynski's life, the analysis provided the basis for an affidavit signed by Terry Turchie, the head of the entire investigation, in support of the application for a search warrant.[92]

David Kaczynski had tried to remain anonymous, but he was soon identified. Within a few days an FBI agent team was dispatched to interview David and his wife with their attorney in Washington, D.C. At this and subsequent meetings, David provided letters written by his brother in their original envelopes, allowing the FBI task force to use the postmark dates to add more detail to their timeline of Ted's activities. David developed a respectful relationship with behavioral analysis Special Agent Kathleen M. Puckett, whom he met many times in Washington, D.C., Texas, Chicago, and Schenectady, New York, over the nearly two months before the federal search warrant was served on Kaczynski's cabin.[105]

David had once admired and emulated his older brother but had since left the survivalist lifestyle behind.[106] He had received assurances from the FBI that he would remain anonymous and that his brother would not learn who had turned him in, but his identity was leaked to CBS News in early April 1996. CBS anchorman Dan Rather called FBI director Louis Freeh, who requested 24 hours before CBS broke the story on the evening news. The FBI scrambled to finish the search warrant and have it issued by a federal judge in Montana; afterwards, the FBI conducted an internal leak investigation, but the source of the leak was never identified.[106]

FBI officials were not unanimous in identifying Ted as the author of the manifesto. The search warrant noted that several experts believed the manifesto had been written by another individual.[48]

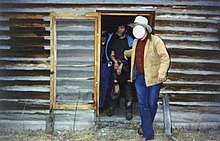

Arrest[]

FBI agents arrested an unkempt Kaczynski at his cabin on April 3, 1996. A search revealed a cache of bomb components, 40,000 hand-written journal pages that included bomb-making experiments, descriptions of the Unabomber crimes and one live bomb, ready for mailing. They also found what appeared to be the original typed manuscript of Industrial Society and Its Future.[107] By this point, the Unabomber had been the target of the most expensive investigation in FBI history at the time.[8][108] A 2000 report by the United States Commission on the Advancement of Federal Law Enforcement stated that the task force had spent over $50 million throughout the course of the investigation.[109]

After his capture, theories emerged naming Kaczynski as the Zodiac Killer, who murdered five people in Northern California from 1968 to 1969. Among the links that raised suspicion was the fact that Kaczynski lived in the San Francisco Bay Area from 1967 to 1969 (the same period that most of the Zodiac's confirmed killings occurred in California), that both individuals were highly intelligent with an interest in bombs and codes, and that both wrote letters to newspapers demanding the publication of their works with the threat of continued violence if the demand was not met. Yet Kaczynski's whereabouts could not be verified for all of the killings. Since the gun and knife murders committed by the Zodiac Killer differed from Kaczynski's bombings, authorities did not pursue him as a suspect. Robert Graysmith, author of the 1986 book Zodiac, said the similarities are "fascinating" but purely coincidental.[110]

The early hunt for the Unabomber portrayed a perpetrator far different from the eventual suspect. Kaczynski consistently uses "we" and "our" throughout Industrial Society and Its Future. At one point in 1993 investigators sought an individual whose first name was "Nathan" because the name was imprinted on the envelope of a letter sent to the media.[54] When authorities presented the case to the public, they denied that there was ever anyone other than Kaczynski involved in the crimes.[96]

Guilty plea[]

A federal grand jury indicted Kaczynski in June 1996 on ten counts of illegally transporting, mailing, and using bombs.[111] Kaczynski's lawyers, headed by Montana federal public defenders Michael Donahoe and Judy Clarke, attempted to enter an insanity defense to avoid the death penalty, but Kaczynski rejected this strategy. On January 8, 1998, he asked to dismiss his lawyers and hire Tony Serra as his counsel; Serra had agreed not to use an insanity defense and instead promised to base a defense on Kaczynski's anti-technology views.[112][113][114] After this request was unsuccessful, Kaczynski tried to kill himself on January 9.[115] Sally Johnson, the psychiatrist who examined Kaczynski, concluded that he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.[116] Forensic psychiatrist Park Dietz said Kaczynski was not psychotic but had a schizoid or schizotypal personality disorder.[117] In his 2010 book Technological Slavery, Kaczynski said that two prison psychologists who visited him frequently for four years told him they saw no indication that he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and the diagnosis was "ridiculous" and a "political diagnosis".[118]

On January 21, 1998, Kaczynski was declared competent to stand trial by federal prison psychiatrist Johnson, "despite the psychiatric diagnoses".[119] As he was fit to stand trial, prosecutors sought the death penalty, but Kaczynski avoided that by pleading guilty to all charges on January 22, 1998, and accepting life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. He later tried to withdraw this plea, arguing it was involuntary as he had been coerced to plead guilty by the judge. Judge Garland Ellis Burrell Jr. denied his request, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld that decision.[120][121]

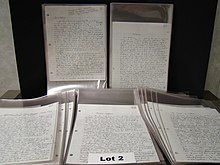

In 2006, Burrell ordered that items from Kaczynski's cabin be sold at a "reasonably advertised Internet auction". Items considered to be bomb-making materials, such as diagrams and "recipes" for bombs, were excluded. The net proceeds went towards the $15 million in restitution Burrell had awarded Kaczynski's victims.[122] Kaczynski's correspondence and other personal papers were also auctioned.[123][124][125] Burrell ordered the removal, before sale, of references in those documents to Kaczynski's victims; Kaczynski unsuccessfully challenged those redactions as a violation of his freedom of speech.[126][127][128] The auction ran for two weeks in 2011, and raised over $232,000.[129]

Incarceration[]

Kaczynski is serving eight life sentences without the possibility of parole at ADX Florence, a supermax prison in Florence, Colorado.[126][130] Early in his imprisonment, Kaczynski befriended Ramzi Yousef and Timothy McVeigh, the perpetrators of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, respectively. The trio discussed religion and politics and formed a friendship which lasted until McVeigh's execution in 2001.[131] In 2012, Kaczynski responded to the Harvard Alumni Association's directory inquiry for the fiftieth reunion of the class of 1962; he listed his occupation as "prisoner" and his eight life sentences as "awards".[132]

The U.S. government seized Kaczynski's cabin, which they put on display at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., until it closed at the end of 2019.[133] In October 2005, Kaczynski offered to donate two rare books to the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies at Northwestern University's campus in Evanston, Illinois, the location of his first two attacks. The Library rejected the offer on the grounds that it already had copies of the works.[134] The Labadie Collection, part of the University of Michigan's Special Collections Library, houses Kaczynski's correspondence with over 400 people since his arrest, including replies, legal documents, publications, and clippings.[135][136] His writings are among the most popular selections in the University of Michigan's special collections.[88] The identity of most correspondents will remain sealed until 2049.[135][137]

Legacy[]

Kaczynski has been portrayed in and inspired multiple artistic works in the realm of popular culture.[138] These include the 1996 television film Unabomber: The True Story,[139] the 2011 play P.O. Box Unabomber,[140] and Manhunt: Unabomber, the 2017 season of the television series Manhunt.[141] The moniker "Unabomber" was also applied to the Italian Unabomber, a terrorist who conducted attacks similar to Kaczynski's in Italy from 1994 to 2006.[142] Prior to the 1996 United States presidential election, a campaign called "Unabomber for President" was launched with the goal of electing Kaczynski as president through write-in votes.[143]

In his book The Age of Spiritual Machines (1999), futurist Ray Kurzweil quoted a passage from Kaczynski's manifesto Industrial Society and Its Future.[144] In turn, Kaczynski was referenced by Bill Joy, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, in the 2000 Wired article "Why the Future Doesn't Need Us". Joy stated Kaczynski "is clearly a Luddite, but simply saying this does not dismiss his argument".[145][146] Professor Jean-Marie Apostolidès has raised questions surrounding the ethics of spreading Kaczynski's views.[147] Various radical movements and extremists have been influenced by Kaczynski.[90] People inspired by Kaczynski's ideas show up in unexpected places, from nihilist, anarchist and eco-extremist movements to conservative intellectuals.[47] Anders Behring Breivik, the perpetrator of the 2011 Norway attacks,[148] published a manifesto which copied large portions from Industrial Society and Its Future, with certain terms substituted (e.g., replacing "leftists" with "cultural Marxists" and "multiculturalists").[149][150]

Over twenty years after Kaczynski's imprisonment, his views have inspired an online community of primitivists and neo-Luddites. One explanation for the renewal of interest in his views is the television series Manhunt: Unabomber, which aired in 2017.[151] Kaczynski is also frequently referred to by ecofascists online.[152] Although some militant fascist and neo-Nazi groups idolize him, Kaczynski described fascism in his manifesto as a "kook ideology" and Nazism as "evil".[151]

Published works[]

Mathematical[]

- Kaczynski, Theodore (June–July 1964). "Another Proof of Wedderburn's Theorem". American Mathematical Monthly. 71 (6): 652–653. doi:10.2307/2312328. JSTOR 2312328. A proof of Wedderburn's little theorem in abstract algebra

- —— (June–July 1964). "Advanced Problem 5210". American Mathematical Monthly. 71 (6): 689. doi:10.2307/2312349. JSTOR 2312349. A challenge problem in abstract algebra

- —— (June–July 1965). "Distributivity and (−1)x = −x (Advanced Problem 5210, with Solution by Bilyeu, R.G.)". American Mathematical Monthly. 72 (6): 677–678. doi:10.2307/2313887. JSTOR 2313887. Reprint and solution to "Advanced Problem 5210" (above)

- —— (July 1965). "Boundary Functions for Functions Defined in a Disk". Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics. 14 (4): 589–612.

- —— (November 1966). "On a Boundary Property of Continuous Functions". Michigan Mathematical Journal. 13 (3): 313–320. doi:10.1307/mmj/1031732782.

- —— (1967). Boundary Functions (fragment) (PhD). University of Michigan. ProQuest 288225414. Kaczynski's doctoral dissertation. Complete dissertation available for purchase from ProQuest, with publication number 6717790.

- —— (March–April 1968). "Note on a Problem of Alan Sutcliffe". Mathematics Magazine. 41 (2): 84–86. doi:10.2307/2689056. JSTOR 2689056. A brief paper in number theory concerning the digits of numbers

- —— (March 1969). "Boundary Functions for Bounded Harmonic Functions" (PDF). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 137: 203–209. doi:10.2307/1994796. JSTOR 1994796. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 16, 2017.

- —— (July 1969). "Boundary Functions and Sets of Curvilinear Convergence for Continuous Functions" (PDF). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 141: 107–125. doi:10.2307/1995093. JSTOR 1995093. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2017.

- —— (November 1969). "The Set of Curvilinear Convergence of a Continuous Function Defined in the Interior of a Cube" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 23 (2): 323–327. doi:10.2307/2037166. JSTOR 2037166. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2017.

- —— (January–February 1971). "Problem 787". Mathematics Magazine. 44 (1): 41. doi:10.2307/2688865. JSTOR 2688865. A challenge problem in geometry

- —— (November–December 1971). "A Match Stick Problem (Problem 787, with Solutions by Gibbs, R.A. and Breisch, R.L.)". Mathematics Magazine. 44 (5): 294–296. doi:10.2307/2688646. JSTOR 2688646. Reprint and solutions to "Problem 787" (above)

Other[]

- Kaczynski, Theodore (1995). Industrial Society and Its Future. The Washington Post.

- Kaczynski, Theodore (2010). Technological Slavery. Feral House. ISBN 978-1-932595-80-2.

- Kaczynski, Theodore (2019). Technological Slavery: Volume 1 (revised and expanded 3rd ed.). Fitch & Madison Publishers. ISBN 978-1-944228-01-9..

- Kaczynski, Theodore (2016). Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How. Fitch & Madison Publishers. ISBN 978-1-944228-00-2..

- Kaczynski, Theodore (2020). Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How (expanded 2nd ed.). Fitch & Madison Publishers. ISBN 978-1-9442-2802-6..

Notes[]

- ^ As stated in the "Additional Findings" section of the FBI affidavit, where a balanced listing of other uncorrelated evidence and contrary determinations also appeared, "203. Latent fingerprints attributable to devices mailed and/or placed by the UNABOM subject were compared to those found on the letters attributed to Theodore Kaczynski. According to the FBI Laboratory no forensic correlation exists between those samples."[48]

- ^ Kaczynski's brother, David—who would play a vital role in Kaczynski's capture by alerting federal authorities to the prospect of his brother's involvement in the Unabomber case—sought out and became friends with Wright after Kaczynski was detained in 1996. David Kaczynski and Wright have remained friends and occasionally speak together publicly about their relationship.[60]

References[]

- ^ "Inmate Locator". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ "Video: Unabomber captured in 1996 after 17 years on the run". ABC News. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Mahan & Griset (2008), p. 132.

- ^ Haberfeld & von Hassell (2009), p. 40.

- ^ Marbella, Jean (April 7, 1996). "Berkeley recalls little about bomb suspect Assistant professor left few traces in 1969 when he abruptly quit TTC". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021.

- ^ Gautney (2010), p. 199.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Excerpts From Letter by 'Terrorist Group', FC, Which Says It Sent Bombs". The New York Times. April 26, 1995. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Howlett, Debbie (November 13, 1996). "FBI Profile: Suspect is educated and isolated". USA Today.

The 17-year search for the bomber has been the longest and costliest investigation in FBI history.

- ^ "The Unabomber's family photo album". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l McFadden, Robert D. (May 26, 1996). "Prisoner of Rage – A special report.; From a Child of Promise to the Unabom Suspect". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017.

- ^ Kovaleski, Serge F.; Adams, Lorraine (June 16, 1996). "A Stranger in the Family Picture". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017.

- ^ Chase (2004), p. 161.

- ^ "The Kaczynski brothers and neighbors". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ Chase (2004), pp. 107–108.

- ^ "Kaczynski: Too smart, too shy to fit in". USA Today. Associated Press. November 13, 1996.

- ^ Ferguson, Paul (1997). "A loner from youth". CNN. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008.

- ^ Karr-Morse (2012), p. 102.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Achenbach, Joel; Kovaleski, Serge F. (April 7, 1996). "The Profile of a Loner". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Martin, Andrew; Becker, Robert (April 16, 1996). "Egghead Kaczynski Was Loner in High School". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017.

- ^ Hickey (2003), p. 268.

- ^ Song, David (May 21, 2012). "Theodore J. Kaczynski". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017.

- ^ Knothe, Alli; Andersen, Travis (May 23, 2012). "Unabomber lists self as 'prisoner' in Harvard directory". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017.

- ^ "Unabomber in Harvard reunion note". BBC. May 24, 2012. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Stampfl, Karl (March 16, 2006). "He came Ted Kaczynski, he left The Unabomber". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Alston, Chase (June 2000). "Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber". The Atlantic Monthly. 285 (6). Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Moreno, Jonathan D (May 25, 2012). "Harvard's Experiment on the Unabomber, Class of '62". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ Haas, Michaela (February 25, 2016). "My Brother, the Unabomber". Medium. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (March 2, 2003). "A Dangerous Mind". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2018.

- ^ Moreno (2012).

- ^ "MKUltra: Inside the CIA's Cold War mind control experiments". The Week. July 21, 2017. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017.

- ^ Chase (2003), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Jad Abumrad (June 28, 2010). "Oops" (Podcast). WNYC Studios. Event occurs at 12:31.

- ^ Sperber (2010), p. 41.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ostrom, Carol M. (April 6, 1996). "Unabomber Suspect Is Charged – Montana Townsfolk Showed Tolerance For 'The Hermit'". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008.

- ^ Wiehl (2020), pp. 78–79.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Booth, William (September 12, 1998). "Gender Confusion, Sex Change Idea Fueled Kaczynski's Rage, Report Says". The Washington Post.

- ^ Magid, Adam K. (August 29, 2009). "The Unabomber Revisited: Reexamining the Use of Mental Disorder Diagnoses as Evidence of the Mental Condition of Criminal Defendants". Indiana Law Journal. S2CID 142388669 – via Semantic Scholar.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Crenson, Matt (July 21, 1996). "Kaczynski's Dissertation Would Leave Your Head Spinning". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016.

- ^ Perez-Pena, Richard (April 5, 1996). "On the Suspect's Trail: the Suspect; Memories of His Brilliance, And Shyness, but Little Else". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017.

- ^ Graysmith (1998), pp. 11–12.

- ^ "125 Montana Newsmakers: Ted Kaczynski". Great Falls Tribune. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ Kifner, John (April 5, 1996). "On the suspect's trail: Life in montana; gardening, bicycling and reading exotically". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015.

- ^ Brooke, James (March 14, 1999). "New portrait of Unabomber: Environmental saboteur around Montana village for 20 years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017.

- ^ Chase (2003), p. 332

- ^ Kingsnorth, Paul. "Dark Ecology". Orion Magazine. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Kaczynski (2016), p. 50.

- ^ Jump up to: a b John H. Richardson (December 11, 2018). "Children of Ted Two decades after his last deadly act of ecoterrorism, the Unabomber has become an unlikely prophet to a new generation of acolytes". New York.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Affidavit of Assistant Special Agent in Charge". Court TV. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "The Unabomber: A Chronology (1978–1982)". Court TV. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ "Ted Kaczynski's Family on 60 Minutes". CBS News. September 15, 1996. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ "Kaczynski was fired '78 after allegedly harassing co-worker". USA Today. Associated Press. November 13, 1996.

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (April 19, 1996). "Woman Denies Romance With Unabomber Suspect". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015.

- ^ Marx, Gary; Martin, Andrew (April 5, 1996). "Survivors See Little Sense Behind the Terror". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blumenthal, Ralph; Kleinfield, N. R. (December 18, 1994). "Death in the Mail – Tracking a Killer: A special report.; Investigators Have Many Clues and Theories, but Still No Suspect in 15 Bombings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017.

- ^ "The end of anon: literary sleuthing from Shakespeare to Unabomber". The Guardian. August 16, 2001. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ Graysmith (1998), pp. 286, 289.

- ^ "Patrick Fischer dies at 75; target of Unabomber". Los Angeles Times. September 3, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Unabomber: A Chronology (1985–1987)". Court TV. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Claiborne, William (April 11, 1996). "Kaczynski Beard May Confuse Witness". The Washington Post.

- ^ Lavandera, Ed (June 6, 2008). "Unabomber's brother, victim forge unique friendship". CNN. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008.

- ^ Locke, Michelle (April 7, 1996). "Not Knowing Where to Look, Unabomber Hunters Looked Everywhere". Associated Press.

- ^ Yates, Nona (January 23, 1998). "Recap of the Unabomber Case". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Unabomber: A Chronology (1988–1995)". Court TV. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. v. Kaczynski Trial Transcripts". Court TV. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "The Unabomber's Targets: An Interactive Map". CNN. 1997. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008.

- ^ Lardner, George; Adams, Lorraine (April 14, 1996). "To Unabomb Victims, a Deeper Mystery". The Washington Post. p. A01. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011.

- ^ Kaczynski, Theodore. "Industrial Society and Its Future" (PDF). editions-hache.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Chase (2004), p. 84.

- ^ Boxall, Bettina; Connell, Rich; Ferrell, David (June 30, 1995). "Unabomber Sends New Warnings". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011.

- ^ Staff writer(s) (April 21, 1996). "A Delicate Dance". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017.

- ^ Elson, John (July 10, 1995). "Murderer's Manifesto". Time. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (September 19, 1995). "Unabomber Manuscript is Published: Public Safety Reasons Cited in Joint Decision by Post, N.Y. Times". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Statement by Papers' Publishers". The Washington Post. September 19, 1995. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011.

- ^ Crain, Caleb (1998). "The Bard's fingerprints". Lingua Franca: 29–39. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Excerpts from Unabomber document". United Press International. September 19, 1995. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017.

- ^ Kaczynski (1995), p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Adams, Brooke (April 11, 1996). "From His Tiny Cabin to the Lack Of Electricity And Water, Kaczynski's Simple Lifestyle in Montana Mountains Coincided Well With His Anti-Technology Views". Deseret News. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017.

- ^ Katz, Jon (April 17, 1998). "The Unabomber's Legacy, Part I". Wired. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ Malendowicz, Paweł (2020). "The Concept of "the Return to the Past" as an Inspiration for the Anti-Civilization Project of Utopian Primitivist Thought". Studia Politologiczne. 53: 200–214. doi:10.33896/SPolit.2019.53.11. ISSN 1640-8888.

Kaczynski himself negated primitivist thought, claiming that all primitive communities fed on some kind of animal food, none of them was vegan, there was no gender equality in most of them ... there was rivalry, which often assumed violent forms, some communities protected nature, but others devastated it through excessive hunting or careless use of fire.

- ^ Fleming, Sean (May 7, 2021). "The Unabomber and the origins of anti-tech radicalism". Journal of Political Ideologies: 1–19. doi:10.1080/13569317.2021.1921940. ISSN 1356-9317.

- ^ Moen, Ole Martin (August 23, 2018). "The Unabomber's ethics". Bioethics. 33 (2): 223–229. doi:10.1111/bioe.12494. hdl:10852/76721. ISSN 1467-8519. PMID 30136739. S2CID 52070603.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sale, Kirkpatrick (September 25, 1995). "Is There Method in His Madness?". The Nation. p. 306.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (September 25, 1995). "Is There Method in His Madness?". The Nation. p. 308.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Didion, Joan (April 23, 1998). "Varieties of Madness". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ Nast, Condé (May 20, 2011). "The Unabomber Returns". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ News, Deseret (January 16, 1998). "Kaczynski's actions prove he is not insane". Deseret News. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Chase, Alston (June 1, 2000). "Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Young, Jeffrey R. (May 25, 2012). "The Unabomber's Pen Pal". The Chronicle of Higher Education. The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. 58 (37): B6–B11. ISSN 0009-5982. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- ^ Bailey, Holly (January 28, 2016). "The Unabomber takes on the Internet". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on February 14, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fleming, Sean (2021). "The Unabomber and the origins of anti-tech radicalism". Journal of Political Ideologies: 1–19. doi:10.1080/13569317.2021.1921940. ISSN 1356-9317.

- ^ Graysmith (1998), p. 74.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Taylor, Michael (May 5, 1998). "New Details Of Stakeout in Montana". SFGate. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018.

- ^ "Unabomber". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Franks, Lucinda (July 22, 1996). "Don't Shoot". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008.

- ^ Labaton, Stephen (October 7, 1993). "Clue and $1 million Reward in Case of the Serial Bomber". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kaczynski, David (September 9, 2007). "Programme 9: 9th September 2007". RTÉ Radio 1. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Johnston, David (April 5, 1996). "On the Suspect's Trail: the Investigation; Long and Twisting Trail Led To Unabom Suspect's Arrest". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017.

- ^ Perez-Pena, Richard (April 7, 1996). "Tapestry of Links in the Unabom Inquiry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Claiborne, William (August 21, 1998). "FBI Gives Reward to Unabomber's Brother". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011.

- ^ Kovaleski, Serge F.; Thomas, Pierre (April 9, 1996). "Brother Hired Own Investigator". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Belluck, Pam (April 10, 1996). "In Unabom Case, Pain for Suspect's Family". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017.

- ^ Kovaleski, Serge F. (July 15, 2001). "His Brother's Keeper". The Washington Post.

- ^ Davis, Pat (January–February 2017). "Historian Spotlight – James Fitzgerald". The FBI National Academy Associates Inc. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018.

- ^ Davies, Dave (August 22, 2017). "FBI Profiler Says Linguistic Work Was Pivotal in Capture Of Unabomber". National Public Radio, Inc. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018.

- ^ Johnston, David (May 5, 1998). "17-Year Search, an Emotional Discovery and Terror Ends". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dubner, Stephen J. (October 18, 1999). "I Don't Want To Live Long. I Would Rather Get The Death Penalty Than Spend The Rest of My Life in Prison". Time. Archived from the original on December 4, 2002. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "Unabomber suspect is caught, ending eight-year man-hunt". CNN. 1996. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008.

- ^ "The Unabomb Trial". CNN. 1997. Archived from the original on June 18, 2006.

- ^ Federal Commission on the Advancement of Federal Law Enforcement (2000). "Law Enforcement in a New Century and a Changing World". NCJ 181343.

- ^ Fagan, Kevin; Wallace, Bill (May 14, 1996). "Kaczynski, Zodiac Killer – the Same Guy?". SFGate. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011.

- ^ Gladstone, Mark (June 19, 1996). "Kaczynski Indicted in 4 Unabomber Attacks". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Glaberson, William (January 8, 1998). "Kaczynski Tries Unsuccessfully to Dismiss His Lawyers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Kaczynski Demands to Represent Himself". Wired. Reuters. January 8, 1998. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017.

- ^ Glaberson, William (January 8, 1998). "Kaczynski Can't Drop Lawyers Or Block a Mental Illness Defense". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013.

- ^ "Suspected Unabomber in suicide attempt". BBC News. January 9, 1998. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017.

- ^ Suzanne, Marmion (September 12, 1998). "Unabomber's Psychiatric Profile Reveals Gender Identity Struggle". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Diamond, Stephen A. (April 8, 2008). "Terrorism, Resentment and the Unabomber". Psychology Today.

- ^ Kaczynski (2010), p. 42.

- ^ Possley, Maurice (January 21, 1998). "Doctor Says Kaczynski Is Competent For Trial". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017.

- ^ Weinstein, Henry (February 13, 2001). "Retrial Rejected for Unabomber". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "The Unabomber: A Chronology (The Trial)". Court TV. Archived from the original on June 30, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ Taylor, Michael (August 12, 2006). "Unabomber's journal, other items to be put up for auction online". SFGate. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008.

- ^ Prendergast, Catherine (2009). "The Fighting Style: Reading the Unabomber's Strunk and White". College English. 72 (1): 10–28. ISSN 0010-0994. JSTOR 25653005 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Perrone, Jane (July 27, 2005). "Crime Pays". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017.

- ^ Hong-Gong, Lin II; Lee, Wendy (July 26, 2005). "Unabomber 'Murderabilian' for Sale". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kovaleski, Serge F. (January 22, 2007). "Unabomber Wages Legal Battle to Halt the Sale of Papers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline (August 13, 2008). "Unabomber Objects to Newseum's Exhibit". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 10, 2008.

- ^ Egelko, Bob (January 9, 2009). "Unabomber's items can be auctioned". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009.

- ^ Kravets, David (June 2, 2011). "Photo Gallery: Weird Government 'Unabomber' Auction Winds Down". Wired. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012.

- ^ "Theodore John Kaczynski Register Number: 04475-046". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Bailey, Holly (January 29, 2016). "The Unabomber's not-so-lonely prison life". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017.

- ^ Knothe, Alli (May 23, 2012). "Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, lists himself in Harvard 1962 alumni report; says 'awards' include eight life sentences". Boston.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Newseum – Unabomber". Newseum. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ Pond, Lauren (October 31, 2005). "NU rejects Unabomber's offer of rare African books". The Daily Northwestern. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Herrada, Julie (2003). "Letters to the Unabomber: A Case Study and Some Reflections" (PDF). Archival Issues. 28 (1): 35–46.

- ^ Bailey, Holly (January 25, 2016). "Letters from a serial killer: Inside the Unabomber archive". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016.

It has been almost 20 years since Ted Kaczynski's trail of terror came to an end. Now a huge trove of his personal writings has come to light, revealing the workings of his mind—and the life he leads behind bars.

- ^ "Labadie Manuscripts". University of Michigan Library. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Gabriel, Trip (April 21, 1996). "Popular Culture Sets Sights on Unabomber". The New York Times.

- ^ Canton, Maj. "Unabomber: The True Story". Radio Times.

- ^ "P.O. Box Unabomber". 36 Monkeys.

- ^ Pedersen, Erik (June 5, 2017). "'Manhunt: Unabomber' Trailer: FBI Profiler Hunts An Unusual Serial Killer". Deadline Hollywood.

- ^ "Italian 'Unabomber' strikes again". BBC News. April 26, 2003.

- ^ Winokur, Scott (September 17, 1996). "The "Unabomber for President" campaign". SFGate.

- ^ Diamond, Jason (August 17, 2017). "Flashback: Unabomber Publishes His 'Manifesto'". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Joy, Bill (April 1, 2000). "Why the Future Doesn't Need Us". Wired.

- ^ Young, Jeffrey R. (May 20, 2012). "The Unabomber's Pen Pal". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ Haven, Cynthia (February 1, 2010). "Unabomber's writings raise uneasy ethical questions for Stanford scholar". Stanford University.

- ^ Hall, John (April 16, 2012). "Anders Breivik admits massacre but pleads not guilty claiming it was self defence". The Independent.

- ^ Hough, Andrew (July 24, 2011). "Norway shooting: Anders Behring Breivik plagiarised 'Unabomber'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- ^ Van Gerven Oei, Vincent W. J. (2011). "Anders Breivik: On Copying the Obscure". continent. 1 (3): 213–23. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hanrahan, Jake (August 1, 2018). "Inside the Unabomber's odd and furious online revival". Wired UK. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (March 19, 2019). "Eco-fascism is undergoing a revival in the fetid culture of the extreme right". The Guardian.

Book sources[]

- Chase, Alston (2004). A Mind for Murder: The Education of The Unabomber and the Origins of Modern Terrorism (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32556-0.

- Chase, Alston (2003). Harvard and the Unabomber: the education of an American terrorist (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-02002-1.

- Gautney, Heather (2010). Protest and Organization in the Alternative Globalization Era: NGOs, Social Movements, and Political Parties (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-62024-7.

- Graysmith, Robert (1998). Unabomber: A Desire to Kill (Berkley ed.). New York: Berkeley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-16725-0.

- Haberfeld, M.R.; von Hassell, Agostino, eds. (2009). A New Understanding of Terrorism: Case Studies, Trajectories and Lessons Learned. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-0115-6.

- Hickey, Eric W., ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of Murder and Violent Crime 1st Edition. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0761924371.

- Kaczynski, David (2016). Every Last Tie: The Story of the Unabomber and His Family. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-7500-5.

- Kaczynski, Theodore John (1995). Industrial Society and Its Future. ISBN 979-8636242437.

- Kaczynski, Theodore John (2010). Technological Slavery. Scottsdale, Arizona: . ISBN 978-1944228019.

- Karr-Morse, Robin (2012). Scared Sick: The Role of Childhood Trauma in Adult Disease (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01354-8.

- Mahan, Sue; Griset, Pamala L. (2008). Terrorism in Perspective (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-5015-2.

- Moreno, Jonathan D. (2012). Mind Wars: Brain Science and the Military in the 21st Century. New York: Bellevue Literary Press. ISBN 978-1-934137-43-7.

- Sperber, Michael (2010). Dostoyevsky's Stalker and Other Essays on Psychopathology and the Arts. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-4993-3.

- Wiehl, Lis W. (2020). Hunting the Unabomber: the FBI, Ted Kaczynski, and the capture of America's most notorious domestic terrorist. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-0-7180-9234-4.

External links[]

- 1942 births

- 20th-century American criminals

- 20th-century American mathematicians

- Activists from Illinois

- American anarchists

- American environmentalists

- American hermits

- American male criminals

- American people convicted of murder

- American people imprisoned on charges of terrorism

- American people of Polish descent

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Bombers (people)

- Complex analysts

- Criminals from Chicago

- Fugitives

- Harvard College alumni

- Inmates of ADX Florence

- Insurrectionary anarchists

- Living people

- Mathematicians from Illinois

- Neo-Luddites

- People convicted of murder by the United States federal government

- People from Evergreen Park, Illinois

- People from Lewis and Clark County, Montana

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by the United States federal government

- School bombings in the United States

- Simple living advocates

- Social critics

- University of California, Berkeley College of Letters and Science faculty

- University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts alumni