Ecofascism

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (April 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Green politics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Neo-fascism |

|---|

|

|

|

Ecofascism is a theoretical political model in which a totalitarian government would require individuals to sacrifice their own interests to the "organic whole of nature".[1]

Some writers have used it to refer to hypothetical future governments, which might resort to fascist policies in order to deal with environmental issues.[1] Other writers have used it to refer to segments of historical[2][3] and modern[4] fascist movements that focused on environmental issues.

Definition[]

Environmental historian Michael E. Zimmerman defines "ecofascism" as "a totalitarian government that requires individuals to sacrifice their interests to the well-being of the 'land', understood as the splendid web of life, or the organic whole of nature, including peoples and their states".[1] Zimmerman argues that while no ecofascist government has existed so far, "important aspects of it can be found in German National Socialism, one of whose central slogans was "Blood and Soil".[1]

Vice has defined Eco-fascism as an ideology "which blames the demise of the environment on overpopulation, immigration, and over-industrialization, problems that followers think could be partly remedied through the mass murder of refugees in Western countries."[5] Environmentalist author Naomi Klein has suggested that Eco-fascists' primary objectives are to close borders to immigrants and, on the more extreme end, to embrace the idea of climate change as a divinely-ordained signal to begin a mass purge of sections of the human race. Ecofascism is "environmentalism through genocide", opined Klein.[6]

Ideological origins[]

Madison Grant[]

Sometimes dubbed the "founding father" of eco-fascism,[7][8] Madison Grant was a pioneer of conservationism in America in the late 19th and early 20th century. Grant is credited as a founder of modern wildlife management. Grant built the Bronx River Parkway, was a co-founder of the American Bison Society, and helped create Glacier National Park, Olympic National Park, Everglades National Park and Denali National Park. As president of the New York Zoological Society, he founded the Bronx Zoo in 1899.[9]

But in addition to his conservation work, Grant was a trenchant racist. In 1906 Grant supported the placing of Ota Benga, a member of the Mbuti people kidnapped from the Congo, on display in the Bronx Zoo as an exhibit in the Monkey House.[7][8] In 1916 Grant wrote The Passing of the Great Race, a piece of pseudoscience which claimed to give an account of the anthropological history of Europe. The book divides Europeans into three races; Alpines, Mediterraneans and Nordics, and makes the case that the first two are inferior to the superior Nordics, who are the only race fit to rule the earth. Adolf Hitler would later describe Grant's book as "his bible" and Grant's "Nordic theory" became a bedrock of Nazi thought.[9][10][11] Additionally, Grant was a eugenicist: He was director of the American Eugenics Society and advocated for the culling of the unfit from the human population. Grant concocted a 100-year plan to perfect the human race which involved killing off ethnic group after ethnic group until racial purity had been obtained.[7] Grant campaigned for the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924, which drastically reduced the number of immigrants from Eastern Europe and Asia allowed into the United States.[11]

In the modern era, Grant's ideas have been cited by ultra-right figures such as Richard Spencer[9] and Anders Breivik.[8][12]

Nazism[]

The authors Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier suggest that the synthesis of fascism and environmentalism began with Nazism. In their book Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience, they note the Nazi Party's interest in ecology, and suggest their interest was "linked with traditional agrarian romanticism and hostility to urban civilization". Richard Walther Darré, a leading Nazi ideologist who invented the term "Blood and Soil", developed a concept of the nation having a mystic connection with their homeland, and as such, the nation was dutybound to take care of the land. Because of this, modern ecofascists cite the Nazi Party as an origin point of ecofascism.[13][14]

After the outlawing of the neo-nazi Socialist Reich Party, one of its members August Haußleiter moved towards organizing within the environmental and anti-nuclear movements, going on to become a founding member of the German Green Party. When green activists later uncovered his past activities in the neo-nazi movement, Haußleiter was forced to step down as the party's chairman, although he continued to hold a central role in the party newspaper. As efforts to expel nationalist elements within the party continued, a conservative faction split off and founded the Ecological Democratic Party, which became noted for persistent holocaust denial, rejection of social justice and opposition to immigration.[15]

Savitri Devi[]

Savitri Devi was a prominent proponent of Esoteric Nazism and deep ecology. A fanatical supporter of Hitler and the Nazi Party from the 1930s onwards, she also supported animal rights activism and was a vegetarian from a young age. She put forward ecologist views in her works, such as the Impeachment of Man (1959), in which she declared her views on animal rights and nature. According to her, human beings do not stand above the animals; but in her ecologist views, humans are rather a part of the ecosystem and should respect all life, including animals and the whole of nature. Because of her dual devotion to both Nazism and deep ecology, she is considered an influential figure in ecofascist circles.[16][17]

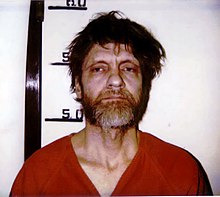

Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber[]

Ted Kaczynski, better known as "The Unabomber", is a figure cited as highly influential upon ecofascist thought. Between 1978 and 1995 Kaczynski instigated a terrorist bombing campaign aimed at inciting a revolution against modern industrial society, in the name of returning humanity to a primitive state he suggested offered humanity more freedom while protecting the environment. In 1995 Kaczynski offered to end his bombing campaign if The Washington Post or The New York Times would publish his 35,000-word Unabomber manifesto. Hoping to save lives, both newspapers agreed to those terms. The manifesto railed not only against modern industrial society but also against "leftists", whom Kaczynski defined as "mainly socialists, collectivists, 'politically correct' types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists and the like".[18]

Because of Kaczynski's intelligence and ability to write in a high-level academic tone, his manifesto was given serious consideration upon release and became highly influential, even amongst those who severely disagreed with his use of violence. Kaczynski's staunchly radical pro-green, anti-left work was quickly absorbed into ecofascist thought.[13]

Kaczynski also criticized the right wing for their support for technological and economic progress while complaining about a decay of tradition, stating that technology erodes traditional social mores that conservatives and right wingers want to protect, and referred to conservatives as fools.[19]

Although Kaczynski and his manifesto has been embraced by ecofascists,[13] he totally rejected fascism.[20] In his manifesto Kaczynski wrote that he considered fascism a "kook ideology" and Nazism as "evil".[20] Kaczynski never tried to align himself with the far right at any point before or after his arrest.[20]

In 2017 Netflix released a dramatisation of Kaczynski's life, entitled Manhunt: Unabomber. The popularity of the show thrust Kaczynski and his manifesto once again into the public's mind and raised the profile of ecofascism.[13][14][20]

Garrett Hardin, Pentti Linkola, and "Lifeboat Ethics"[]

Two figures influential in ecofascism are Garrett Hardin and Pentti Linkola, both of whom were proponents of what they refer to as "Lifeboat Ethics". Hardin was an American ecologist accused by the Southern Poverty Law Center of being a white nationalist,[21] whilst Linkola was a Finnish ecologist accused of being an active ecofascist who actively advocated ending democracy and replacing it with dictatorships that would use totalitarian and even genocidal tactics to end climate change.[22] Both men used versions of the following analogy to illustrate their viewpoint:

What to do, when a ship carrying a hundred passengers suddenly capsizes and there is only one lifeboat? When the lifeboat is full, those who hate life will try to load it with more people and sink the lot. Those who love and respect life will take the ship's axe and sever the extra hands that cling to the sides[13][14]

Association with violence and mass shootings[]

The perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings described himself as an ecofascist,[23][24] ethno-nationalist, and racist[25] in his manifesto The Great Replacement, named after a far-right conspiracy theory[26] originating in France. Jordan Weissmann, writing for Slate, describes the perpetrator's version of ecofascism as "an established, if somewhat obscure, brand of neo-Nazi"[27] and quotes Sarah Manavis of New Statesman as saying, "[Eco-fascists] believe that living in the original regions a race is meant to have originated in and shunning multiculturalism is the only way to save the planet they prioritise above all else".[27] Similarly, Luke Darby clarifies it as: "eco-fascism is not the fringe hippie movement usually associated with ecoterrorism. It's a belief that the only way to deal with climate change is through eugenics and the brutal suppression of migrants."[28]

The suspect in the 2019 El Paso shooting is believed to have written a similar manifesto, professing support for the Christchurch shooter.[29] Posted to the online message board 8chan,[30] it blames immigration to the United States for environmental destruction,[31] saying that American lifestyles were "destroying the environment",[32] invoking an ecological burden to be borne by future generations,[24][28] and concluding that the solution was to "decrease the number of people in America using resources".[32]

The Swedish self-identified ecofascist Green Brigade is an eco-terrorist group linked to The Base that is responsible for multiple mass murder plots. The Green Brigade has been responsible for arson attacks against targets deemed to be enemies of nature, like attack on a mink farm that caused multi-million-dollar damages. Two members were arrested by Swedish police, allegedly planning assassinating judges and bombings.[33][34]

In December 2020, the Swedish Defence Research Agency released a report on ecofascism. The paper argued that ecofascism is intimately tied to the ideology of accelerationism, and ecofascists nearly exclusively choose terror tactics over the political approach. Further, the SDRA argues not all ecofascist mass shooters have been recognized as such: Pekka-Eric Auvinen who shot eight people in Finland before killing himself adhered to the ideology according to his manifesto titled "The Natural Selector's Manifesto". He advocated "total war against humanity" due to the threat humanity posed to other species. He wrote that death and killing is not a tragedy, as it constantly happens in nature between all species. Auvinen also wrote that the modern society hinders "natural justice" and that all inferior "subhumans" should be killed and only the elite of humanity be spared. In one of his YouTube videos Auvinen paid tribute to the prominent ecofascist Pentti Linkola.[37]

William H. Stoetzer, a member of the Atomwaffen Division, an organization responsible for at least eight murders, was active in the Earth Liberation Front as late as 2008 and joined Atomwaffen in 2016.[38]

Critiques[]

According to deep ecologic activist and writer David Orton, the term is pejorative in nature and it has "social ecology roots, against the deep ecology movement and its supporters plus, more generally, the environmental movement. Thus, 'ecofascist' and 'ecofascism', are used not to enlighten but to smear." Orton argues that "it is a strange term/concept to really have any conceptual validity" as there has not "yet been a country that has had an "eco-fascist" government or, to my knowledge, a political organization which has declared itself publicly as organized on an ecofascist basis."[39]

Accusations of ecofascism have often been made but are usually strenuously denied.[39][40] Such accusations have come from both sides of the political spectrum. Those on the political left see it as an assault on human rights, as in social ecologist Murray Bookchin's use of the term. Detractors on the political right include Rush Limbaugh and other conservative and wise use movement commentators. In the latter case, it is often a hyperbolic term for all environmental activists, including more mainstream groups such as Greenpeace and the Sierra Club.[40]

Bookchin's critique of deep ecology[]

Murray Bookchin criticizes the political position of deep ecologists such as David Foreman:

There are barely disguised racists, survivalists, macho Daniel Boones, and outright social reactionaries who use the word ecology to express their views, just as there are deeply concerned naturalists, communitarians, social radicals, and feminists who use the word ecology to express theirs... It was out of this former kind of crude eco-brutalism that Hitler, in the name of "population control," with a racial orientation, fashioned theories of blood and soil... The same eco-brutalism now reappears a half-century later among self-professed deep ecologists who believe that Third World peoples should be permitted to starve to death and that desperate Indian immigrants from Latin America should be excluded by the border cops from the United States lest they burden "our" ecological resources.[41]

Sakai on "natural purity"[]

Such observations among the left are not exclusive to Bookchin. In his review of Anna Bramwell's biography of Richard Walther Darré, political writer J. Sakai and author of Settlers: The Mythology of the White Proletariat, observes the fascist ideological undertones of natural purity.[42] Prior to the Russian Revolution, the tsarist intelligentsia was divided on the one hand between liberal "utilitarian naturalists", who were "taken with the idea of creating a paradise on earth through scientific mastery of nature" and influenced by nihilism as well as Russian zoologists such as Anatoli Petrovich Bogdanov; and, on the other, "cultural-aesthetic" conservationists such as Ivan Parfenevich Borodin, who were influenced in turn by German Romantic and idealist concepts such as Landschaftspflege and Naturdenkmal.[43]

Far-Right Green Movements[]

France[]

Nouvelle Droite movement[]

The European Nouvelle Droite movement, developed by Alain de Benoist and other individuals involved with the GRECE think tank, have also combined green politics with right-wing ideas such as European ethnonationalism.[44]

Germany[]

German conservatives have published a magazine, Umwelt und Aktiv, that masquerades as a garden and nature publication but intertwines garden tips with racial slurs. This is known as a “camouflage publication” in which the NPD, or far-right National Democratic Party, can spread its mission and ideologies through a discrete source and make its way into homes they otherwise wouldn’t. Right-wing environmentalists are settling in the northern regions of rural Germany and are forming nationalistic and authoritarian communities which produce honey, fresh produce, baked goods, and other such farm goods for profit. Their ideology is centered around “blood and soil” ruralism in which they humanely raise produce and animals for profit and sustenance. Through their support of this operation, and the backing of many others, it’s reported that the NPD is trying to wrestle the green movement, which has been dominated by the left since the 1980s, back from the left through these avenues.

It’s difficult to know if when one is buying local produce or farm fresh eggs from a farmer at their stand, they’re supporting a right-wing agenda. Various efforts are being made to halt or slow the infiltration of right-wing ecologists into the community of organic farmers such as brochures about their communities and common practices. However, as the organic cultivation organization, Biopark, demonstrates with their vetting process, it’s difficult to keep people out of communities because of their ideologies. Biopark specifies that they vet based on cultivation habits, not opinions or doctrines. Especially when they’re not explicitly stated.[45]

Collegium Humanum[]

United Kingdom[]

Throughout its history, the far-right British National Party has flirted on and off with environmentalism. During the 1970s the party's first leader John Bean expressed support for the emerging environmentalist movement in the pages of the party's newspaper and suggested the primary cause of pollution as overpopulation, and therefore immigration into Britain must be halted.[46] During the 2000s the BNP sought to position itself as the "only 'true' green party in the United Kingdom, dedicating a significant portion of their manifestos to green issues. During an appearance on BBC One's Question Time in October 2009, then-leader Nick Griffin proclaimed:

Unlike the fake "Greens" who are merely a front for the far left of the Labour regime, the BNP is the only party to recognise that overpopulation – whose primary driver is immigration, as revealed by the government's own figures – is the cause of the destruction of our environment. Furthermore, the BNP's manifesto states that a BNP government will make it a priority to stop building on green land. New housing should wherever possible be built on derelict "brown land".[47]

The Guardian criticised Griffin's claims that himself and the BNP were truly environmentalists at heart, suggesting it was merely a smokescreen for anti-immigrant rhetoric and pointed to previous statements by Griffin in which he suggested that climate change was a hoax.[47] These suspicions seemed to be proven correct when in December 2009 the BNP released a 40-page document denying that global warming is a "man-made" phenomena.[48] The party reiterated this stance in 2011, as well as making claims that wind farms were the of cause the deaths of "thousands of Scottish pensioners from hypothermia".[49]

Hungary[]

The far-right Hungarian political party Our Homeland Movement has adopted some elements of enviromentalism; for example, the party has called on Hungarians to show patriotism by supporting the removal of pollution from the Tisza River while simultaneously placing the blame on the pollution on Romania and Ukraine.[50] Similarly, elements of the far-right Sixty-Four Counties Youth Movement proscribe themselves to the "Eco-Nationalist" label, with one member stating "no real nationalist is a climate denialist".[51]

Slovakia[]

In Slovakia, the far-right People's Party Our Slovakia of Marian Kotleba, the fourth biggest party in the country, has a strong focus on environmental protection and farming.[52]

Serbia[]

Leviathan Movement promotes ecology and protects animals from cruelty by, among other things, saving them from abusers. Leviathan used to share an office with the Serbian Right, a far-right political party, and Leviathan ’s leader, Pavle Bihali, is seen in pictures on his social media accounts posing with neo-Nazis.[52]

In media[]

Themes of eco-fascism can be found in films like Soylent Green, Hunger Games, Z.P.G., and Fortress.

See also[]

- Animal welfare in Nazi Germany

- ATWA

- Definitions of fascism

- Eco-nationalism

- Eco-terrorism

- Individualists Tending to the Wild

- Ecoauthoritarianism

- Fascism

- Neo-Luddism

- Occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

- Radical environmentalism

- Red-green-brown alliance

References[]

- ^ a b c d Zimmerman, Michael E. (2008). "Ecofascism". In Taylor, Bron R. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, Volume 1. London, UK: Continuum. pp. 531–532. ISBN 978-1-44-112278-0.

- ^ "...the phenomenon one might call "actually existing ecofascism", that is, the preoccupation of authentically fascist movements with environmentalist concerns". Peter Staudenmeier, "Fascist Ecology: The 'Green Wing' of the Nazi Party and its Historical Antecedents in Germany". In "Ecofascism: Lessons from the German experience", by Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier, 1995. Staudenmeier's and Biehl's book was based on the research results of Marie-Luise Heuser, "Was grün begann endete blutigrot. Von der Naturromantik zu den Reagrarisierungs- und Entvölkerungsplänen der SA und SS". In: Dieter Hassenpflug (Hrsg.): Industrialismus und Ökoromantik. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, 1991, ISBN 9783824440771. She showed that the SS extermination programs were based on ecological motives.

- ^ Olsen, Jonathan. 1999. Nature and Nationalism: Right-Wing Ecology and the Politics of Identity. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- ^ Matthew Phelan (2018-10-22). "The Menace of Eco-Fascism". New York Review of Books.

- ^ Kamel, by Zachary; Lamoureux, Mack; Makuch, Ben (20 January 2020). "'Eco-fascist' Arm of Neo-Nazi Terror Group, The Base, Linked to Swedish Arson". Vice. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Corcione, Adryan (30 April 2020). "Eco-fascism: What It Is, Why It's Wrong, and How to Fight It". Teen Vogue. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Tucker, Jeffrey A. (17 March 2019). "The Founding Father of Eco-Fascism". American Institute for Economic Research. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Darby, Luke (7 August 2019). "What Is Eco-Fascism, the Ideology Behind Attacks in El Paso and Christchurch?". GQ magazine. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Patin, Katia (19 January 2021). "The rise of eco-fascism". Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Weymouth, Adam (21 April 2021). "Ecofascism: The dark side of environmentalism". Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ a b Sparrow, Jeff (29 November 2019). "Eco-fascists and the ugly fight for 'our way of life' as the environment disintegrates". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Adler-Bell, Sam (24 September 2019). "Why White Supremacists Are Hooked on Green Living". The New Republic. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, Jason (19 March 2019). "Eco-fascism is undergoing a revival in the fetid culture of the extreme right". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Tom (10 April 2019). "Understanding the Alt-Right's Growing Fascination with 'Eco-Fascism'". Vice. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Lee, Martin A. (2000). The Beast Reawakens: Fascism’s Resurgence from Hitler’s Spymasters to Today’s Neo-Nazi Groups and Right-Wing Extremists. New York: Routledge. pp. 217–218. ISBN 0415925460. OCLC 1106702367.

- ^ "Savitri Devi: The mystical fascist being resurrected by the alt-right". BBC. 29 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Didion, Joan (April 23, 1998). "Varieties of Madness". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ "The Unabomber Trial: The Manifesto". The Washington Post. 1997. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Hanrahan, Jake (1 August 2018). "Inside the Unabomber's odd and furious online revival". Wired UK. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Garrett Hardin". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ Adler-Bell, Sam (24 September 2019). "Why White Supremacists Are Hooked on Green Living". NewRepublic.com. New Republic. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Koziol, Michael (15 March 2019). "Christchurch shooter's manifesto reveals". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b Achenbach, Joel (18 August 2019). "Two mass killings a world apart share a common theme: 'ecofascism': Environmental groups denounce racists who cloak themselves in green". The Washington Post – via ProQuest.

- ^ Fisher, Marc; Achenbach, Joel. "Boundless racism, zero remorse: A manifesto of hate and 49 dead in New Zealand". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Darby, Luke (5 August 2019). "How the 'Great Replacement' conspiracy theory has inspired white supremacist killers". The Daily Telegraph. London – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Weissmann, Jordan (15 March 2019). "What the Christchurch Killer's Manifesto Tells Us". Slate. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ a b Darby, Luke (7 August 2019). "What Is Eco-Fascism, the Ideology Behind Attacks in El Paso and Christchurch?". GQ. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Noack, Rick (6 August 2019). "Christchurch endures as extremist touchstone, as investigators probe suspected El Paso manifesto". The Washington Post – via ProQuest.

- ^ Arango, Tim; Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Benner, Katie (3 August 2019). "Minutes Before El Paso Killing, Hate-Filled Manifesto Appears Online". The New York Times.

- ^ Owen, Tess (6 August 2019). "Eco-Fascism: the Racist Theory That Inspired the El Paso and Christchurch Shooters". Vice.

- ^ a b Lennard, Natasha (5 August 2019). "The El Paso Shooter Embraced Eco-Fascism. We Can't Let the Far Right Co-Opt the Environmental Struggle". The Intercept.

- ^ Lamoureux, Mack (December 25, 2020). "Neo-Nazis Are Using Eco-Fascism to Recruit Young People". Vice News.

- ^ Lamoureux, Mack (December 25, 2020). "Alleged Eco-Terrorists Discussed Abortion Clinic Bombing, Assassinating Judge: Court Documents". Vice News.

- ^ Shajkovci, Ardian (27 September 2020). "Eco-Fascist 'Pine Tree Party' Growing as a Violent Extremism Threat". Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Manavis, Sarah (21 September 2018). "Eco-fascism: The ideology marrying environmentalism and white supremacy thriving online". New Statesman. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Kaati, Lisa; Cohen, Katie; Sarnecki, Hannah; Fernquist, Johan; Pelzer, Björn. "Ekofascism. En studie av propaganda i digitala miljöer" [Ecofascism. A study of propaganda in digital environments] (in Swedish). Swedish Defence Research Agency. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Thayer, Nate (6 December 2019). "Secret Identities of U.S. Nazi Terror Group Revealed". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b Orton, David (February 2000). "Ecofascism: What is It? A Left Biocentric Analysis". home.ca.inter.net. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Green historian to Brandis: My Work's Been Abused". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 November 2003. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (Summer 1987). "Social Ecology Versus Deep Ecology: A Challenge for the Ecology Movement". Green Perspectives: Newsletter of the Green Program Project. No. 4–5.

- ^ Sakai, J. (2003). The Green Nazi - an investigation into fascist ecology. Kerspledebeb. ISBN 978-0-9689503-9-5.

- ^ Weiner, Douglas R. (2000). Models Of Nature: Ecology, Conservation, and Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-5733-1.

- ^ "Fascism" by Roger Griffin, in Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, edited by Bron Taylor. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2008. (pp. 639-644)

- ^ "German far-right extremists tap into green movement for support". the Guardian. 2012-04-28. Retrieved 2021-12-02.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (21 April 2020). "Greenshirts – The (Mis)use of Environmentalism by the Extreme Right". Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b Hickman, Leo (22 October 2009). "Nick Griffin's views on climate change and population can only be disdained on Question Time". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Hickman, Leo (16 December 2009). "BNP document proves the far right is at home with climate change denial". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Ward, Bob (11 May 2011). "British election results show climate change denial is not a vote winner". Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Margulies, Morgan (2021). "Eco-Nationalism: A Historical Evaluation of Nationalist Praxes in Environmentalist and Ecologist Movements". Consilience:The Journal of Sustainable Development (23): 22–29. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Lubarda, Balsa (9 February 2021). "When Ecologism Turns (Far) Right: the Hungarian Laboratory". Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b "In 'Far-Right Ecologism', European Extremists Pursue Broader Appeal". Balkan Insight. 2 February 2022.

External links[]

- Ecofascism: What is It?, by David Orton.

- Darker shades of Green, by Derek Wall for Red Pepper.

- An alternative to the new wave of ecofascism, by Micah White for The Guardian, 16 September 2010.

- Eco-fascism: The ideology marrying environmentalism and white supremacy thriving online by Sarah Manavis.

- Fascism

- Green politics

- Political slurs

- Far-right politics

- Deep ecology

- Environmental movements

- Syncretic political movements

- Environmentalism

- Terrorism in Sweden

- Terrorism in the United States

- Terrorism in New Zealand

- Eco-terrorism

- Political ecology