Fascist (insult)

Fascist has been used as a pejorative epithet against a wide range of individuals, political movements, governments, public, and private institutions since the emergence of fascism in Europe in the 1920s. Political commentators on both the Left and the Right accused their opponents of being fascists, starting in the years before World War II. In 1928, the Communist International labeled their social democratic opponents as social fascists,[1] while the social democrats themselves as well as some parties on the political right accused the Communists of having become fascist under Joseph Stalin's leadership.[2] In light of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, The New York Times declared on 18 September 1939 that "Hitlerism is brown communism, Stalinism is red fascism."[3] In 1944, the anti-fascist and socialist writer George Orwell commented that fascism had been rendered almost meaningless by its common use as an insult against various individuals and groups, and posited that in England fascist had become a synonym for bully.[4]

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union was categorized by its former World War II allies as totalitarian alongside fascist Nazi Germany to convert pre-World War II anti-fascism into post-war anti-communism, and debates around the comparison of Nazism and Stalinism intensified.[5] Both sides also used the epithets fascist and fascism against the other. In the Soviet Union, they were used to describe anti-Soviet activism, and East Germany officially referred to the Berlin Wall as the "Anti-Fascist Protection Wall." Across the Eastern Bloc, the term anti-fascist became synonymous with the Communist state–party line and denoted the struggle against dissenters and the broader Western world.[6][7] In the United States, early supporters of an aggressive foreign policy and domestic anti-communist measures in the 1940s and 1950s labeled the Soviet Union as fascist, and stated that it posed the same threat as the Axis Powers had posed during World War II.[8] Accusations that the enemy was fascist were used to justify opposition to negotiations and compromise, with the argument that the enemy would always act in a manner similar to Adolf Hitler or Nazi Germany in the 1930s.[9]

After the end of the Cold War, use of fascist as an insult continued across the political spectrum in many countries. Individuals and groups labeled as fascist by their opponents in the 21st century have included the participants in the Euromaidan demonstrations in Ukraine, the government of Croatia, United States president Donald Trump, and supporters of Sebastián Piñera in Chile. Fascist is also used as an insult to refer to actually-existing fascism as a left-wing ideology, rather than the consensus among scholars that it is a far-right ideology,[5] as a way to blame the tragedies of the 20th century on the left alone and erase leftist victims of fascist violence.[10]

Usage[]

Soviet and Russian politics[]

The Bolshevik movement and later the Soviet Union made frequent use of the fascist epithet coming from its conflict with the early German and Italian fascist movements. It was widely used in press and political language to describe either its ideological opponents, such as the White movement, or even internal fractions of the socialist movement, such as social democracy, were called social fascism and even regarded by communist parties as the most dangerous form of fascism).[11] In Germany, the Communist Party of Germany, which had been largely controlled by the Soviet leadership since 1928, used the epithet fascism to describe both the Social Democrats and the Nazi movement; in Soviet usage, the German Nazis were described as fascists until 1939, when the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was signed, after which Nazi–Soviet relations started to be presented positively in Soviet propaganda. Accusations that the leaders of the Soviet Union during the Stalin era acted as red fascists were commonly stated by both left-wing and right-wing critics.[12]

After Operation Barbarossa in 1941, fascist was used in the Soviet Union to describe virtually any anti-Soviet activity or opinion. In line with the Third Period, fascism was the "final phase of crisis of bourgeoisie", which "in fascism sought refuge" from "inherent contradictions of capitalism", and almost every Western capitalist country was fascist, with the Third Reich being just the "most reactionary" one.[13][14] The international investigation on Katyn massacre was described as "fascist libel"[15] and the Warsaw Uprising as "illegal and organised by fascists."[16] Polish Communist Służba Bezpieczeństwa described Trotskyism, Titoism, and imperialism as "variants of fascism."[17]

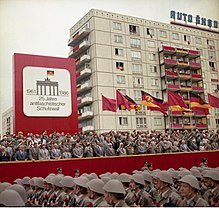

This use continued into the Cold War era and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The official Soviet version of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was described as "Fascist, Hitlerite, reactionary and counter-revolutionary hooligans financed by the imperialist West [which] took advantage of the unrest to stage a counter-revolution."[18] Some rank-and-file Soviet soldiers reportedly believed they were being sent to East Berlin to fight German fascists.[19] The Soviet-backed German Democratic Republic's official name for the Berlin Wall was the Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart (German: Antifaschistischer Schutzwall).[20] After the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai denounced the Soviet Union for "fascist politics, great power chauvinism, national egoism and social imperialism", comparing the invasion to the Vietnam War and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia.[21] During the Barricades in January 1991, which followed the May 1990 "On the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia" independence declaration of the Republic of Latvia from the Soviet Union, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union declared that "fascism was reborn in Latvia."[22]

During the Euromaidan demonstrations in January 2014, the Slavic Anti-Fascist Front was created in Crimea by Russian member of parliament Aleksey Zhuravlyov and Crimean Russian Unity party leader and future head of the Republic of Crimea Sergey Aksyonov to oppose "fascist uprising" in Ukraine.[23][24] After the February 2014 Ukrainian revolution, through the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation and the outbreak of the war in Donbass, Russian nationalists and state media used the term. They frequently described the Ukrainian government after Euromaidan as fascist or Nazi,[25][26] at the same time using antisemitic canards, such as accusing them of "Jewish influence", and stating that they were spreading "gay propaganda", a trope of anti-LGBT activism.[27]

Western politics[]

In 1944, the acclaimed English writer, democratic socialist, and anti-fascist George Orwell wrote about the term's overuse as an epithet, arguing: "It will be seen that, as used, the word 'Fascism' is almost entirely meaningless. In conversation, of course, it is used even more wildly than in print. I have heard it applied to farmers, shopkeepers, Social Credit, corporal punishment, fox-hunting, bull-fighting, the 1922 Committee, the 1941 Committee, Kipling, Gandhi, Chiang Kai-Shek, homosexuality, Priestley’s broadcasts, Youth Hostels, astrology, women, dogs and I do not know what else. ... [T]he people who recklessly fling the word 'Fascist' in every direction attach at any rate an emotional significance to it. By 'Fascism' they mean, roughly speaking, something cruel, unscrupulous, arrogant, obscurantist, anti-liberal and anti-working-class. Except for the relatively small number of Fascist sympathizers, almost any English person would accept 'bully' as a synonym for 'Fascist'. That is about as near to a definition as this much-abused word has come."[28] In 2004, Samantha Power, a lecturer at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, reflected Orwell's words from 60 years prior when she stated: "Fascism – unlike communism, socialism, capitalism, or conservatism – is a smear word more often used to brand one's foes than it is a descriptor used to shed light on them."[29]

In the 1980s, the term was used by leftist critics to describe the presidency of Ronald Reagan. The term was later used in the 2000s to describe the presidency of George W. Bush by its critics and in the late 2010s to describe the candidacy and presidency of Donald Trump. In her 1970 book Beyond Mere Obedience, radical activist and theologian Dorothee Sölle coined Christofascist to describe fundamentalist Christians.[30][31][32] In 2006, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) found contrary to the Article 10 (freedom of expression) of the ECHR fining a journalist for calling a right-wing journalist "local neo-fascist", regarding the statement as a value-judgment acceptable in the circumstances.[33]

In response to multiple authors claiming that the then-presidential candidate Donald Trump was a fascist,[34][35][36][37] a 2016 article for Vox cited five historians who study fascism, including Roger Griffin, author of The Nature of Fascism, who stated that Trump either does not hold and even is opposed to several political viewpoints that are integral to fascism, including viewing violence as an inherent good and an inherent rejection of or opposition to a democratic system.[38] A growing number of scholars have posited that the political style of Trump resembles that of fascist leaders, beginning with his election campaign in 2016,[39][40] continuing over the course of his presidency as he appeared to court far-right extremists,[41][42][43][44] including his failed efforts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election results after losing to Joe Biden,[45] and culminating in the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[46] As these events have unfolded, some commentators who had initially resisted applying the label to Trump came out in favor of it, including conservative legal scholar Steven G. Calabresi and conservative commentator Michael Gerson.[47][48] After the attack on the Capitol, the historian of fascism Robert O. Paxton went so far as to state that Trump is a fascist, despite his earlier objection to using the term in this way.[49] Other historians of fascism such as Richard J. Evans,[50] Griffin, and Stanley Payne continue to disagree that fascism is an appropriate term to describe Trump's politics.[46]

American politics[]

In the United States, fascist is used as an insult to imply that Nazism, and by extension fascism, was a socialist and left-wing ideology, which is contrary to the consensus among scholars of fascism.[5] An example of this is conservative columnist Jonah Goldberg's book Liberal Fascism, where modern liberalism and progressivism in the United States are described as the child of fascism. Writing for The Washington Post, historian Ronald J. Granieri stated that this "has become a silver bullet for voices on the right like Dinesh D'Souza and Candace Owens: Not only is the reviled left, embodied in 2020 by figures like [Bernie] Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Elizabeth Warren, a dangerous descendant of the Nazis, but anyone who opposes it can't possibly have ties to the Nazis' odious ideas. There is only one problem: This argument is untrue."[5] Another example are Republican Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene's numerous statements, such as comparing mask mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic to Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. According to cultural critic writing for NBC News, in an effort to erase leftist victims of Nazi violence, "they've actually inverted the truth, implying that Nazis themselves were leftists", and "are part of a history of far-right disavowal, projection and escalation intended to provide a rationale for retaliation."[10]

Chilean politics[]

In Chile, the insult facho pobre ("poor fascist") has been the subject of significant analysis, including figures such as Alberto Mayol and Carlos Peña González.[51][52] The insult was used in the aftermath of the 2017 Chilean general election, where right-wing Sebastián Piñera won the presidency, against those who voted for right-wing candidates.[53] Peña González calls the essence of the insult "the worst of the paternalisms: the belief that ordinary people ... does not know what they want and betrays their true interest at the time of choise",[53] while writer states that the insult is a sort of "left-wing classism" (Spanish: roteo de izquierda) and imply that "certain ideas can only be defended by the priviledged class."[51]

Serbian politics[]

In Serbian politics, the fascist label is often reserved for inflammatory statements and dehumanization of Croats and Croatia. During the Croatian War of Independence in 1991, Serb-controlled Yugoslav Counterintelligence Service launched Operation Labrador as a false flag operation, intended to bomb Jewish cemeteries in Zagreb, in order to portray then internationally unrecognised Croatian government as fascist and undermine their chances for international recognition.[54] In modern Serbia, Dragan J- Vučićević, editor-in-chief of Serbian Progressive Party's propaganda flagship Informer, holds belief that the "vast majority of Croatian nation are Ustaše" and thus fascists.[55] The same notion is sometimes drawn through his tabloid's writings.[56] Aleksandar Vulin, one of the country's leading politicians, also frequently comments on Croatia in a similar manner.[57][58][59] After he was banned from entering to Croatia, Vulin commented the ban by saying that modern Croatia is a "follower of [Ante] Pavelić's fascist ideology."[60]

Marxist explanations for broad uses[]

Several Marxist theories back up particular uses of fascism beyond its usual remit. Nicos Poulantzas's theory of state monopoly capitalism could be associated with the idea of a military-industrial complex to suggest that the 1960s United States had a fascist social structure, although this kind of Maoist or Guevarist analysis often underpinned the rhetorical depiction of Cold War authoritarians as fascists. In a 1969 interview with the Viking Youth Power Hour, Abbie Hoffman stated: "They employ massive overkill strategy, there are 30, 20 to 30 marshals daily inside the courtroom, it has the atmosphere of an arms camp, the law against us is rigged ... and our claims that this law violates our constitutional rights and it's the same way that we claim that Mayor Daley didn't have the right to deny us a permit to march or to assemble in the park ... . I think it points a direction in the future which is that the government embarked on a course of fascism."[61]

Some Marxist groups, such as the Indian section of the Fourth International and Mansoor Hekmat-led or influenced groups in Iran and Iraq, have provided analytical accounts as to why fascist should be applied to groups like the Hindutva movement, the Iranian regime born after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, or the Islamist sections of the Iraqi insurgency. Other scholars contend that the traditional meaning of fascism does not apply to Hindutva groups and may hinder an analysis of their activities.[62][63][64][65]

See also[]

- Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire

- Definitions of fascism

- Godwin's law

- Nazi analogies

- Political insult

- Red-baiting

- Reductio ad Hitlerum

References[]

- ^ Haro, Lea (2011). "Entering a Theoretical Void: The Theory of Social Fascism and Stalinism in the German Communist Party". Critique: Journal of Socialist Theory. 39 (4): 563–582. doi:10.1080/03017605.2011.621248.

- ^ Adelheid von Saldern, The Challenge of Modernity: German Social and Cultural Studies, 1890-1960 (2002), University of Michigan Press, p. 78, ISBN 0-472-10986-3.

- ^ "Editorial: The Russian Betrayal". The New York Times. 18 September 1939.

- ^ Orwell, George (1944). "What is Fascism?" George Orwell. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Granieri, Ronald J. (5 February 2020). "The right needs to stop falsely claiming that the Nazis were socialists". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Agethen, Manfred; Jesse, Eckhard; Neubert, Ehrhart (2002). Der missbrauchte Antifaschismus. Freiburg: Verlag Herder. ISBN 978-3451280177.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2008). Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. Pan Macmillan. p. 54. ISBN 9780330472296.

- ^ Adler, Les K.; Paterson, Thomas G. (April 1970). "Red Fascism: The Merger of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in the American Image of Totalitarianism, 1930's–1950's". The American Historical Review. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 75 (4): 1046–1064. doi:10.2307/1852269. JSTOR 1852269.

- ^ Adler, Les K.; Paterson, Thomas G. (April 1970). "Red Fascism: The Merger of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in the American Image of Totalitarianism, 1930's–1950's". The American Historical Review. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 75 (4): 1046–1064. doi:10.2307/1852269. JSTOR 1852269.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berlatsky, Noah (8 July 2021). "Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene can't stop making Covid-Nazi comparisons". NBC News. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Draper, Theodore (February 1969). "The Ghost of Social-Fascism". Commentary: 29–42.

- ^ Adler, Les K.; Paterson, Thomas G. (April 1970). "Red Fascism: The Merger of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in the American Image of Totalitarianism, 1930's–1950's". The American Historical Review. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 75 (4): 1046–1064. doi:10.2307/1852269. JSTOR 1852269.

- ^ "Наступление фашизма и задачи Коммунистического Интернационала в борьбе за единство рабочего класса против фашизма". 7th Comintern Congress. 20 August 1935. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "Фашизм – наиболее мрачное порождение империализма". История второй мировой войны 1939–1945 гг. 1973. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Robert Stiller, "Semantyka zbrodni"

- ^ "1944 – Powstanie Warszawskie". e-Warszawa.com. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "Dane osoby z katalogu funkcjonariuszy aparatu bezpieczeństwa – Franciszek Przeździał". Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. 1951. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Kendall, Bridget (6 July 2017). The Cold War: A New Oral History of Life Between East and West. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4735-3087-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Fryer, Peter (1957). "The Second Soviet Intervention". Hungarian Tragedy. London: D. Dobson. ASIN B0007J7674. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006 – via Vorhaug.net.

- ^ "Goethe-Institut – Topics – German-German History Goethe-Institut". 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ Rea, Kenneth W. (1975). "Peking and the Brezhnev Doctrine". Asian Affairs. 3 (1): 22–30. ISSN 0092-7678 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga".

- ^ Shynkarenko, Oleg (18 February 2014). "The Battle for Kiev Begins". Daily Beast. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Elizabeth A. Wood (2015). Roots of Russia's War in Ukraine. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- ^ Shuster, Simon (20 October 2014). "Russians Re-write History to Slur Ukraine Over War". Time. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (20 March 2014). "Fascism, Russia, and Ukraine". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Wagstyl, Stefan. "Fascism: a useful insult". Financial Times.

- ^ Rosman, Artur Sebastian (February 19, 2019). "Orwell Watch #27: What is fascism? Does anybody know?" Stanford University. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Power, Samantha (May 2, 2014). "The Original Axis of Evil". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Dorothee Sölle (1970). Beyond Mere Obedience: Reflections on a Christian Ethic for the Future. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House.

- ^ "Confessing Christ in a Post-Christendom Context". The Ecumenical Review. 1 July 2000. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

... shall we say this, represent this, live this, without seeming to endorse the kind of christomonism (Dorothee Solle called it 'Christofascism'! ...

- ^ Pinnock, Sarah K. (2003). The Theology of Dorothee Soelle. Trinity Press International. ISBN 1-56338-404-3.

... of establishing a dubious moral superiority to justify organized violence on a massive scale, a perversion of Christianity she called Christofascism. ...

- ^ "Case of Karman v. Russia (Application no. 29372/02) Judgment". European Court of Human Rights. 14 March 2007.

- ^ "'Racist', 'fascist', 'utterly repellent': What the world said about Donald Trump". BBC News. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Gopnik, Adam (11 May 2016). "Going There with Donald Trump". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Swift, Nathan (26 October 2015). "Donald Trump's fascist tendencies". The Highlander. Highlander Newspaper. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Hodges, Dan (9 December 2015). "Donald Trump is an outright fascist who should be banned from Britain today". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (19 May 2016). "I asked 5 fascism experts whether Donald Trump is a fascist. Here's what they said". Vox. Vox Media. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Kagan, Robert (18 May 2016). "This is how fascism comes to America". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ McGaughey, Ewan (2018). "Fascism-Lite in America (or the Social Ideal of Donald Trump)". British Journal of American Legal Studies. 7 (2): 291–315. doi:10.2478/bjals-2018-0012. S2CID 195842347. SSRN 2773217.

- ^ Stanley, Jason (15 October 2018). "If You're Not Scared About Fascism in the U.S., You Should Be". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (30 October 2018). "Donald Trump borrows from the old tricks of fascism". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Gordon, Peter (7 January 2020). "Why Historical Analogy Matters". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Szalai, Jennifer (10 June 2020). "The Debate Over the Word Fascism Takes a New Turn". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Cummings, William; Garrison, Joey; Sergent, Jim (6 January 2021). "By the numbers: President Donald Trump's failed efforts to overturn the election". USA Today. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Matthews, Dylan (14 January 2020). "The F Word: The debate over whether to call Donald Trump a fascist, and why it matters". Vox. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Calabresi, Steven G. (20 July 2020). "Trump Might Try to Postpone the Election. That's Unconstitutional". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Gerson, Michael (1 February 2021). "Trumpism is American fascism". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Paxton, Robert O. (11 January 2021). "I've Hesitated to Call Donald Trump a Fascist. Until Now". Newsweek. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. (13 January 2021). "Why Trump isn't a fascist". The New Statesman. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "¿Qué es ser un facho pobre?". The Clinic (in Spanish). 15 November 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Carlos Peña y el concepto de 'facho pobre': 'Los insultos a la gente que votó a la derecha revelan una grave incomprensión'". El Desconcierto (in Spanish). 31 December 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peña, Carlos (31 December 2017). "Facho pobre". El Mercurio.

- ^ "19. kolovoza 1991. - Operacija Labrador i Opera". Hrvatska radiotelevizija. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Razgovor s vlasnikom Informera, najzloćudnijeg tabloida Balkana: Vučićeviću, jeste li vi budala?". Novi list (in Croatian). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Đorđević, Jelena. "Kako Informerova matematika 'dokazuje' da su skoro svi Hrvati ustaše". Raskrinkavanje.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Blebne i ostane živ! Vulin pljuje po Hrvatima kad god stigne..." 24 sata. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Tko je Aleksandar Vulin, Vučićev jastreb, koji je opet dao skandalozne izjave o Hrvatima". Večernji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Srpski ministar obrane: Vučić ne treba ići u Hrvatsku, tamo će ga na trgovima dočekati ustaše". T.portal. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Vulin o zabrani ulaska: Hrvatska je sljedbenica fašističke Pavelićeve ideologije". Radiosarajevo.ba (in Bosnian). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Hoffman, Abbie; Laporte, Toma (November 1969). "An Interview About the Trial with Abbie Hoffman".

- ^ Chatterjee, Surojit (19 December 2003). "RSS neither Nationalist nor Fascist, Indian Christian priest's research concludes". The Christian Post. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006.

- ^ P. Venugopal (August 23, 1998). "RSS neither nationalist nor fascist, says Christian priest after research". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on July 22, 2004.

- ^ Walter K. Andersen, Shridhar D. Damle (May 1989). "The Brotherhood in Saffron: The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Hindu Revivalism". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 503: 156–57. doi:10.1177/0002716289503001021. S2CID 220839484.

- ^ Ethnic and Racial Studies, Volume 23, Number 3, May 2000, pp. 407–441 ISSN 0141-9870 print/ISSN 1466-4356 online.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fascism |

- Masso, Iivi (19 February 2009). "Fašism kui propaganda tööriist". (Fascism as a tool of propaganda). Eesti Päevaleht. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights

- Fascism

- Pejorative terms for people

- Political terminology