Eoin O'Duffy

This article uses bare URLs, which may be threatened by link rot. (May 2021) |

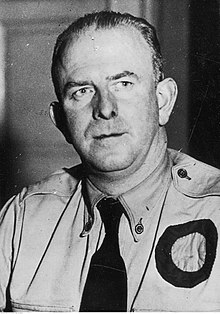

General Eoin O'Duffy | |

|---|---|

O'Duffy speaking at a rally in September 1934 | |

| Leader of Fine Gael | |

| In office 4 May 1933 – 16 June 1934 | |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | W. T. Cosgrave |

| Garda Commissioner | |

| In office 30 September 1922 – 4 February 1933 | |

| Preceded by | Michael Staines |

| Succeeded by | Eamon Broy |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office May 1921 – August 1923 | |

| Constituency | Monaghan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Owen Duffy 28 January 1890 Lough Egish, County Monaghan, Ireland |

| Died | 30 November 1944 (aged 54) Dublin, Ireland |

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery, Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Political party | Sinn Féin (1917–1922) Fine Gael (1933–1934) National Corporate Party (1935–1937) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Irish Volunteers Irish Republican Brotherhood Irish Republican Army National Army Irish Brigade |

| Years of service | 1917–1933 1936–1937 |

| Rank | General Chief of Staff |

| Battles/wars | Irish War of Independence Irish Civil War Spanish Civil War |

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy, 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was a fascist Irish nationalist politician, military commander and police commissioner. He was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a prominent figure in the Ulster IRA during the Irish War of Independence. In this capacity he became Chief of Staff of the IRA in 1922. He accepted the Anglo-Irish Treaty and served as a general in the National Army in the Irish Civil War, on the pro-Treaty side.

O'Duffy became the second Commissioner of the Garda Síochána, the police force of the new Irish Free State, after the Civic Guard Mutiny and the subsequent resignation of Michael Staines. He had been an early member of Sinn Féin. He was elected as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Monaghan, his home county, during the 1921 election. After a split in Sinn Féin in 1923, he became associated with Cumann na nGaedheal and led the movement known as the Blueshirts. After the merger of various pro-Treaty factions under the banner of Fine Gael, O'Duffy was the party leader for a short time, before leaving the party in 1934.

O'Duffy was attracted to the various fascist movements on the continent. He raised the Irish Brigade to fight for Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War as an act of Catholic solidarity and was inspired by Benito Mussolini's Italy to found the National Corporate Party. During the Second World War, he offered to Nazi Germany the prospect of raising an Irish Brigade to fight against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front, but this was not taken up.

O'Duffy was active in multiple sporting bodies, including the Gaelic Athletic Association and the Irish Olympic Council.

Early life[]

Eoin O'Duffy was born Owen Duffy in Lough Egish, near Castleblayney, County Monaghan, on 28 January 1890 to an impoverished smallholder family.[1] He was the youngest of seven children. His father, also named Owen Duffy, had inherited his 15-acre farm from his father Peter in 1888, however the family were forced to farm conacre land and work on the roads to make ends meet. O'Duffy attended Laggan national school.[2] He graduated to a school in Laragh where he developed an interest in the Gaelic Revival and attended night classes hosted by the Gaelic League.[3] He was close to his mother, Bridget Fealy, who died of cancer when he was 12.[4] O'Duffy was devastated by her death and he wore her ring for the rest of his life.[5]

In 1909, he sat the king's scholarship examination for St Patrick's College, Dublin, but as a place was not assured, he applied to become a clerk in the county surveyor's office in Monaghan. O'Duffy decided to pursue a career as a surveyor and came fifth in the local government board examination in 1912.[6] O'Duffy was appointed and moved to Newbliss to take up his new position.[7] He later secured a post as an engineer.

Involvement in sport[]

Ulster GAA[]

O'Duffy was a leading member of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) in Ulster. He was appointed secretary of the Ulster Provincial Council in 1912. He later served as Treasurer of the GAA Ulster Council from 1921 to 1934. His important role in developing the GAA in Ulster is memorialised by the O'Duffy Terrace at the principal provincial stadium, St Tiernach's Park in Clones, County Monaghan.[8] In December 2009 a plaque was erected in memory of O'Duffy in Aughnamullen. The plaque was unveiled by the President of the Ulster GAA Council, Tom Daly.[9]

He was also a member of Harps' Gaelic football club.[2]

Other sports[]

As well as being a prominent figure in Ulster GAA he was also active in other sports. He was President of the Irish Amateur Handball Association from 1926 to 1934, the National Athletic and Cycling Association from 1931 to 1934 (which he founded in 1922), and the Irish Olympic Council from 1931 to 1932.[2]

O'Duffy believed in the ideal of "cleaned manliness". He said sport "cultivates in a boy habits of self-control [and] self-denial" and promotes "the cleanest and most wholesome of the instincts of youth". He said a lack of sport caused some boys to have "failed to keep their athleticism, but became weedy youths, smoking too soon, drinking too soon".[10]

Political activities[]

Irish Republican Army and Sinn Féin[]

In 1917, O'Duffy joined the Irish Volunteers and took an active part in the Irish War of Independence, after that organisation became the Irish Republican Army (IRA). He rose rapidly through the ranks. He started off as the Section Commander of the Clones Company, then Captain, then Commandant and finally appointed Brigadier in 1919.[2] He came to the attention of Michael Collins, who enrolled him in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and supported his advancement in the movement's hierarchy.[11][12] One year later, Collins described O'Duffy as "the best man in Ulster".[13] O'Duffy's senior involvement in the GAA and knowledge of Monaghan from his job as a surveyor proved invaluable for organisation and recruitment.[14]

In 1918 O'Duffy became secretary of Sinn Féin's north Monaghan area council.[15] On 14 September 1918 he and Daniel Hogan were arrested after a GAA match and charged with "illegal assembly". He was imprisoned in Belfast Prison and released on 19 November 1918.[2] After his release O'Duffy focused on organising his brigade and built an effective intelligence network by cultivating contacts with susceptible RIC men. He was forced to go on the run after an RIC raid on his house in September 1919 but continued to draw his salary from the Monaghan county council.[16]

On 15 February 1920, he (along with Ernie O'Malley) was involved in the first capture of a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks by the IRA in Ballytrain, in his native Monaghan. The raid boosted local IRA recruitment, shook RIC morale and resulted in the closure of many barracks in rural Monaghan.[17] O'Duffy was once again arrested and imprisoned in Belfast Prison, where he went on hunger strike.[18] He was released in June and arranged which Sinn Féin candidates would stand in Monaghan during the 1920 Irish local elections.[19]

O'Duffy's brigade started raiding the homes of Protestants for arms, increasing sectarian tensions.[20] Armed Orangemen begun parading the roads of Unionist areas and tit-for-tat killings occurred in reprisal for IRA casualties incurred during raids.[21] He supported the Belfast Boycott and his brigade began harassing of Protestant stores, burning delivery vans from Belfast, raiding trains carrying northern goods and sabotaging rail-tracks.[22]

O'Duffy became more ruthless in 1921, intensifying attacks on British forces and executions of suspected informers and other opponents of the IRA.[23] When a Protestant trader named George Lester held up and searched two boys he suspected of being dispatch carriers for the IRA in February 1921, O'Duffy ordered his death. Lester was shot but survived his injury. In retaliation the B Specials invaded Rosslea on 23 February and sacked the Catholic part of the town. One month later the IRA, commanded by O'Duffy, raided the town in reprisal, burning fourteen houses and killing three Protestants, two of them B Specials.[24]

He became director of the army in 1921. In May 1921 he was returned as a Sinn Féin TD for the Monaghan constituency to the Second Dáil.[25] He was re-elected at the 1922 general election.[26]

In March 1921, he was made commander of the IRA's 2nd Northern Division. Following the Truce with the British in July 1921, he was sent to Belfast. After the rioting known as Belfast's Bloody Sunday, he was given the task of liaising with the British to try to maintain the Truce and defend Catholic areas against attack. During this time he gained the nickname "Give 'em the lead" after delivering a belligerent speech in South Armagh threatening that if unionists "decided they were against Ireland and against their fellow countrymen" the IRA would "have to use the lead against them".[27] He was Director of Organisation in Ulster and Chief Liaison officer for Ulster at the time the treaty was signed.[28]

In January 1922 he became IRA Chief of Staff, replacing Richard Mulcahy. O'Duffy was the youngest general in Europe until Francisco Franco was promoted to that rank.[citation needed]

Civil War General and Garda Síochána[]

In 1921 he supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty, being pessimistic about the IRA's chances should the war resume and seeing the treaty as a stepping stone to a republic.[29] On 14 January, Dan Hogan was arrested in Derry by the B Specials. In response O'Duffy proposed the kidnapping of a hundred prominent Orangemen in Fermanagh and Tyrone to Collins. The raid was executed on 7 February.[30] On 22 April, O'Duffy accused Liam Lynch's 1st Southern Division of retaining arms intended for the Northern IRA. Lynch in turn blamed O'Duffy for the arms not reaching the north.[31]

He served as a general in the National Army and was given control of the South-Western Command.[2] In the ensuing Irish Civil War he was one of the architects behind the Free State's strategy of seaborne landings in Republican-held areas. He took Limerick for the Free State in July 1922, before being held up in the Battle of Killmallock south of the city. The enmities of the civil war era were to stay with O'Duffy throughout his political career.[citation needed]

In September 1922, Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O'Higgins was experiencing indiscipline within the recently formed Garda Síochána and O'Duffy was appointed Garda Commissioner after resigning from the army in order to take up the position. O'Duffy was a fine organiser and has been given much of the credit for the emergence of a largely respected, non-political and unarmed police force. He insisted on a Catholic ethos to distinguish the Gardaí from their Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) predecessors, and regularly told members of the force they were not just men working an ordinary job, but policemen fulfilling their religious duty.[32] He was also a vocal opponent of alcohol in the force, instructing Gardaí to avoid it all costs.[33][page needed]

In February, following a general election in 1933 Éamon de Valera dismissed O'Duffy as Garda Commissioner. In the Dáil de Valera explained the reason for his dismissal, stating "[O'Duffy] was likely to be biased in his attitude because of past political affiliations". The true reason, however, appears to have been the new government's discovery that in 1932, O'Duffy's was one of the voices urging W. T. Cosgrave to resort to a military coup rather than to turn over power to the incoming Fianna Fáil administration.[34] O'Duffy refused the offer of another position of equivalent rank in the public service.[35] Ernest Blythe said many years later that the outgoing Government had become so alarmed by O'Duffy's conduct that had they returned to power they would have also acted as De Valera did and dismissed O'Duffy as Garda Commissioner.[36]

Leader of the Blueshirts[]

In July 1933 O'Duffy, urged by Blythe and Thomas F. O'Higgins, became leader of the Army Comrades Association, an organisation set up to protect Cumann na nGaedheal public meetings, which had been disrupted under the slogan "No Free Speech for Traitors" by Irish Republican Army members newly confident after the elections. O'Duffy and many other conservative elements within the Irish Free State began to embrace fascist ideology, which was in vogue at that time and O'Duffy was seen to be an ideal choice to lead the Blueshirts as he was considered charismatic, skilled in organising and also untainted by association with the failures of the previous Cumann na nGaedheal government.[37]

O'Duffy was approved as leader of the ACA on 20 July.[38] He soon changed the name of this new movement to the National Guard. An admirer of the Italian leader Benito Mussolini, O'Duffy and his organisation adopted outward symbols of European fascism such as the straight-arm Roman salute and a distinctive blue uniform. It was not long before they became known as the Blueshirts, similar to the Italian Blackshirts and the German Brownshirts.[citation needed] O'Duffy established a weekly newspaper, the Blueshirt, and published a new constitution that promoted corporatism, Irish unification and opposition to "alien" control and influence.[39]

In August 1933 a parade was planned by the Blueshirts in Dublin to commemorate Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, both of whom had died 11 years earlier. This was an imitation of Mussolini's March on Rome and was perceived as such despite contrary claims. De Valera feared a similar coup d'état as seen in Italy and the Special Branch raided the houses of prominent treatyites to seize their firearms.[40] On 11 August, de Valera reinstated the Constitution (Amendment No. 17) Act 1931, banned the parade and placed Gardaí outside of key locations.[41]

On 22 August the Blueshirts were declared an illegal organisation.[42] To circumvent this ban the movement once again adopted a new name, this time styling itself the League of Youth. In 1933 a group of Irish republicans, one member of which was Dan Keating, planned to assassinate O'Duffy in Ballyseedy, County Kerry, while he would be on his way to a meeting. A man was sent to Limerick to find out which car O'Duffy would be travelling in but the man purposely gave false information and O'Duffy escaped.[43]

During the early stages of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935 O'Duffy offered Benito Mussolini the service of 1000 Blueshirts because he believed the war represented the struggle between civilisation and barbarism. On 18 September, in an interview he said that the Blueshirts were volunteering to fight "not for Italy or against Abyssinia, but for the principle of the corporate system" against which "the forces of both Marxism and of capitalism" were ranged.[44]

O'Duffy and some of his men also made an appearance at the 1934 International Fascist conference in Montreux where he argued against antisemitism, telling the conference that they had "no Jewish problem in Ireland" and that he "could not subscribe to the principle of the persecution of any race".[45][46]

Fine Gael[]

On 24 August 1933, representatives of Cumann na nGaedheal and the National Centre Party approached O'Duffy, offering that the Blueshirts join their ranks in exchange for O'Duffy becoming their leader. On 8 September the Blueshirts, under pressure after de Valera's ban on the organisation, approved the merger and so Cumann na nGaedheal, the Centre Party and the Blueshirt movement merged to form Fine Gael.[47] O'Duffy, though not a TD, became the first leader, with former President of the Executive Council W. T. Cosgrave serving as parliamentary leader and Vice-President. The National Guard, now rechristened the Young Ireland Association, was transformed from an illegal paramilitary group into the militant wing of a political party.

The new party's policy document, published in mid-November 1933, sought the reunification of Ireland within the British Commonwealth but made no mention of a corporatist parliament and committed itself to democracy. As a result, O'Duffy was forced to tone down his anti-democratic rhetoric though many of his Blueshirt colleagues continued to advocate authoritarianism.[48]

Fine Gael meetings were often attacked by IRA members and O'Duffy's touring of rural towns resulted in tensions and violence.[49] On 6 October 1933 O'Duffy was involved in disturbances in Tralee during which he was hit with a hammer on the head and had his car torched as he attempted to attend a Fine Gael convention.[50] De Valera used the violence to justify a crackdown on Blueshirt activities. A raid on the Young Ireland Association found evidence that it was the National Guard under another name, and the organisation was once again banned.[51] O'Duffy responded with a speech in Ballyshannon where referred to himself as a republican and declared that "whenever Mr de Valera runs away from the Republic and arrests you Republicans, and puts you on board beds in Mountjoy, he is entitled to the fate he gave Mick Collins and Kevin O’Higgins".[52] O'Duffy was arrested by the Gardaí several days later.[53] He was initially released on appeal but was summoned to appear before the Military Tribunal two days later and charged with membership of an illegal organisation and incitement to murder the president of the executive council, however they unable to convict him of either charges.[54]

O'Duffy proved an unsuitable leader: he was a soldier rather than a politician, and was temperamental. He resented Cumann na nGaedheal's drift from republicanism following Collins' death in 1922, and insisted that Fine Gael would not "play second fiddle to anybody in the matter of Nationality".[55] O'Duffy's nationalistic views alienated ex-Unionists who had supported Cumann na nGaedheal since the civil war, alarmed pro-Commonwealth moderates in Fine Gael, and resulted in O'Duffy being made the subject of an exclusion order in Northern Ireland.[56] O'Duffy also clashed with his party on economic matters. Whereas Fine Gael favoured a return to pasture farming and free trade, O'Duffy was supportive of the experiments in tillage and protectionism implemented by his Fianna Fáil rivals, and was forced to attempt to compromise between the two.[57]

His Fine Gael colleagues who regarded themselves as defenders of law-and-order were embarrassed by the Blueshirts use of violence and attacks on the Gardaí, in addition to O'Duffy's connections with foreign fascist organisations and his view of the IRA as a communist group.[2] O'Duffy's prestige was damaged when Fine Gael only won majorities on six councils to Fianna Fáil's fifteen in the 1934 Irish local elections after O'Duffy had predicted taking twenty.[58] The cost of Blueshirt activism also began to strain the party financially.[59] O'Duffy's approval of illegal agitation against the collection of land annuities by the government, declaration of his support for a republic and the revelation of his connections with the British Union of Fascists and the Fedrelandslaget were the last straws for moderates in Fine Gael. On 5 and 7 September 1934 Cosgrave, Ned Cronin and James Dillon met O'Duffy resulting in an agreement that O'Duffy could "deliver only carefully prepared and concise speeches from manuscripts" and give interviews "only after consultation and in writing". In response, O'Duffy resigned from the party on 18 September.[60]

After his resignation, O'Duffy denounced Fine Gael as "the pan-British party of the Free State" and claimed he resigned "because he was not prepared to lead the League of Youth with the Union Jack tied to his neck".[61]

Spanish Civil War[]

At first, O'Duffy announced to the press that "he was glad to be out of politics" but in October 1934 he announced his intentions to lead the Blueshirts as an independent movement. The Blueshirts split into two factions, one supporting O'Duffy and the other supporting Ned Cronin's leadership.[62] O'Duffy and Cronin toured the country attempting to win the support of local Blueshirt branches.[63] By 1935 the Blueshirts had disintegrated. Seeking to regain his former political influence, O'Duffy attempted to court the IRA, encouraging his followers to wear Easter lilies and desist from informing on republicans.[64] In June 1935 O'Duffy launched the National Corporate Party, a fascist political party inspired by Italy's Mussolini.

The following year he organised an Irish Brigade to fight for Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War. He was motivated to do so by Ireland's historic link with Spain, his devout anti-communism and a will to defend Catholicism, stating "It is not a conflict between fascism and anti-fascism but between Christ and anti-christ".[50] In London in September 1936 O'Duffy met Juan de la Cierva and Emilio Mola, promising he would recruit an Irish contingent to fight against the Republicans.[65]

Despite the Irish Government advising against participation in the war, 700 of O'Duffy's followers went to Spain to fight on Franco's side. He later stated he had received over 7,000 applications but several complications meant only 700 of these made it to Spain.[66] O'Duffy's men saw little fighting and were sent home by Franco, returning in June 1937.[67] Franco had not been impressed by the Brigade's lack of military expertise and there were bitter arguments among O'Duffy and his officers about the direction of the Brigade.[66]

Later life and death[]

O'Duffy returned to Ireland from Spain in disarray. He wrote a book, Crusade in Spain (1938), about the Irish Brigade in Spain. The book had antisemitic undertones; O'Duffy wrote that trade unions are "powerful political Jewish-Masonic organisations, directed and focused by the Communist International."[2] He later congratulated General Franco for winning the Spanish Civil War; Franco thanked O'Duffy for his sending congratulations "on the victory of the Spanish Army in defence of Christianity, occidental civilisation and humanity, over the forces of destruction and disorder."[68]

In 1936 O'Duffy attended the founding meeting of Cumann Poblachta na hÉireann but never became a member.[69] In 1940 he also attended the founding meeting of Córas na Poblachta along with former leaders of the Irish Christian Front.[70] In 1939 The Irish Times reported that O'Duffy and his followers were trying to set up a new organisation however nothing materialised.[68] He was subsequently put under surveillance by the G2.

In February 1939 he met up with Oskar Pfaus, a German spy whom he put in touch with the IRA. He also met the Italian diplomat Vincenzo Berardis.[2] Berardis assessed O'Duffy as being a committed fascist and noted his approval of the S-Plan and his opposition to de Valera's coercion against the IRA.[71] A month later O'Duffy met Berardis again to solicit his support for a new fascist party that would unite Irish fascists and republicans.[72] He is thought to have met with several leading IRA figures and German diplomat Eduard Hempel in a remote corner of Donegal during the summer of 1939. G2 suspected O'Duffy was "flirting with the IRA" by acting as a negotiator between them and the Germans. At one point O'Duffy was offered a position as an IRA intelligence officer and on another occasion he was invited to join former IRA Chiefs of Staff Moss Twomey and Andy Cooney in a protest against the "Yankee invasion of the Six Counties" in the summer of 1941.[73]

In early November 1940 O'Duffy spoke with German spy Hermann Goertz in a meeting arranged by Seamus O'Donovan. O'Duffy made a good impression on Goertz and put him in contact with General Hugo MacNeill, who met with O'Duffy and German diplomat Henning Thomsen the next month to draw up a bilateral understanding between the Irish army and Germany in the event of a British invasion of Ireland.[74]

In the summer of 1943 O'Duffy approached the German Legation in Dublin with an offer to organise an Irish Volunteer Legion for use on the Eastern Front. He explained his offer to the German ambassador as a wish to "save Europe from Bolshevism". He requested an aircraft to be sent from Germany so that he could conduct the necessary negotiations in Berlin. The offer was "not taken seriously".[75] By this time O'Duffy had developed a serious drinking problem[76] and his health had begun to seriously deteriorate; he died on 30 November 1944, aged 54. He received a state funeral. Following Requiem Mass in St Mary's Pro-Cathedral, he was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.[77]

In 2006 RTÉ aired a documentary entitled Eoin O'Duffy — An Irish Fascist.[78]

Gallery[]

British Army intelligence file for Owen O'Duffy (Eoin O'Duffy)

References[]

- ^ McGarry, Fearghal (2005). Eoin O'Duffy: A Self-Made Hero. OUP Oxford. p. 1. ISBN 0199276552.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Eoin O'Duffy papers" (PDF). National Library of Ireland.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 5

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 6

- ^ "From a Free State hero to a buffoon in a Blueshirt". Irish Independent. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 7

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 8

- ^ Nauright, John; Wiggins, David K., eds. (2016). Sport and Revolutionaries: Reclaiming the Historical Role of Sport in Social and Political Activism. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 9781317519485.

- ^ "General Owen O'Duffy Remembered". Hogan Stand.

- ^ "Violence, citizenship and virility: The making of an Irish fascist". History Ireland.

- ^ Fearghal McGarry, 'O'Duffy, Eoin (1890–1944)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 27

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 26

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 28

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 32

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 42–43

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 48

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 49

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 50

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 52–53

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 54

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 57

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 58–64

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 60

- ^ "Eoin O'Duffy". Oireachtas Members Database. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "Eoin O'Duffy". ElectionsIreland.org. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 78–80

- ^ "Witness Statement of Captain Liam McMullen" (PDF). Bureau of Military History.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 91

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 99

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 98

- ^ McNiffe, Liam (1997). A history of the Garda Síochána. Wolfhound Press. p. 138.

- ^ Wallace, Colm (2017). The Fallen: Gardaí Killed in Service 1922-1949. Dublin: History Press.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 189

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 197

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 188,386

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 207–208

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 209

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 210

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 216

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 217

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 218

- ^ "Spanish Civil War veterans look back". BBC.

- ^ "Eoin O'Duffy's Blueshirts and the Abyssinian Crisis". History Ireland. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL: Pax Romanizing". Time. 31 December 1934. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 254

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 219

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 222–223

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 225

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dwyer, Ryle (31 December 2012). "More recent files devoid of O'Duffy-era detail". www.irishexaminer.com. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 226

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 227

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 228

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 229–230

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 235

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 239

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 241–243

- ^ Collins, Stephen; Meehan, Ciara (7 November 2020). "Without the Blueshirts, there would have been no Fine Gael". Irish Times. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 260

- ^ McGarry (2005), pp. 261–265

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 240

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 270

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 271

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 279

- ^ Fearghal McGarry, Irish Politics and the Spanish Civil War, p. 27

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ireland and the Spanish Civil War". History Ireland.

- ^ Thomas Gunning, former secretary to O'Duffy, was also a "suspect" for Irish Military Intelligence (G2), having remained in Spain after the rest of the Irish volunteers for Franco departed under a cloud of recrimination. Gunning worked as a newspaper correspondent in Spain for a short time then made his way to Berlin, where he worked for the Propaganda Ministry until his death in 1940.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "What O'Duffy Did When He Came Home". The Irish Times.

- ^ Eithne McDermott (1998). Clann Na Poblachta. p. 11. ISBN 9781859181867.

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 332

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 324

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 325

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 338

- ^ McGarry (2005), p. 336

- ^ See Stephan, Enno: Spies in Ireland (1963) p. 232

- ^ Dorney, John (24 October 2018). "'God's Battle': O'Duffy's Irish Brigade in the Spanish Civil War". theirishstory.com. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Staff writer(s) (4 January 2008). "Cemetery's appeal very much alive". The Irish Times.

- ^ "HIDDEN HISTORY: FOUNDING FATHERS. Eoin O'Duffy – an Irish Fascist | RTÉ Presspack".

Further reading[]

- Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O'Duffy: A Self-Made Hero (Oxford University Press, 2005)

- For material on the Irish Bandera at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 October 2009)

- For material on the International Brigadiers from Ireland at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 October 2009).

- Eoin O'Duffy: A Self-Made Hero – Fearghal McGarry interviewed

- A review of McGarry's book at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 October 2009) by Dermot Bolger in the Sunday Independent, (Dublin) 27 November 2005.

- 1892 births

- 1944 deaths

- Antisemitism in Ireland

- Burials at Glasnevin Cemetery

- Chiefs of Staff of the Defence Forces (Ireland)

- Christian fascists

- Early Sinn Féin TDs

- Far-right politics in Ireland

- Fascist politicians

- Garda Commissioners

- Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members

- Irish anti-communists

- Irish fascists

- Irish people of the Spanish Civil War

- Leaders of Fine Gael

- Members of the 2nd Dáil

- Members of the 3rd Dáil

- Members of the Blueshirts

- National Army (Ireland) generals

- Olympic Federation of Ireland officials

- People from County Monaghan

- People of the Irish Civil War (Pro-Treaty side)