Nazi architecture

Nazi architecture is the architecture promoted by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime from 1933 until its fall in 1945, connected with urban planning in Nazi Germany. It is characterized by three forms: a stripped neoclassicism, typified by the designs of Albert Speer; a vernacular style that drew inspiration from traditional rural architecture, especially alpine; and a utilitarian style followed for major infrastructure projects and industrial or military complexes. Nazi ideology took a pluralist attitude to architecture; however, Adolf Hitler himself believed that form follows function and wrote against "stupid imitations of the past".[1]

While similar to Classicism, the official Nazi style is distinguished by the impression it leaves on viewers. Architectural style was used by the Nazis to deliver and enforce their ideology. Formal elements like flat roofs, horizontal extension, uniformity, and the lack of decor created "an impression of simplicity, uniformity, monumentality, solidity and eternity," which is how the Nazi Party wanted to appear.[2]

Adlerhorst bunker complex looked like a collection of Fachwerk (half-timbered) cottages. Seven buildings in the style of Franconian half-timbered houses were constructed in Nuremberg in 1939 and 1940.[3]

German Jewish architects were banned, eg. Erich Mendelsohn and Julius Posener emigrated in 1933.

Forced labor[]

The construction of new buildings served other purposes beyond reaffirming Nazi ideology. In Flossenbürg and elsewhere, the SS built forced-labor camps where prisoners of the Third Reich were forced to mine stone and make bricks, much of which went directly to Albert Speer for use in his rebuilding of Berlin and other projects in Germany. These new buildings were also built by forced-laborers. Working conditions were harsh, and many laborers died. This process of mining and construction allowed Nazis to fulfill political and economic goals simultaneously while creating buildings that fulfilled ideological expression goals.[4]

Welthauptstadt Germania[]

The crowning achievement of this movement was to be Welthauptstadt Germania, the projected renewal of the German capital Berlin following the Nazis' presumed victory of World War II. Speer, who oversaw the project, produced most of the plans for the new city. Only a small portion of the "World Capital" was ever built between 1937 and 1943. The plan's core features included the creation of a great neoclassical city based on an East-West axis with the Berlin victory column at its centre. Major Nazi buildings like the Reichstag or the Große Halle (never built) would adjoin wide boulevards. A great number of historic buildings in the city were demolished in the planned construction zones. However, with defeat of the Third Reich, the work was never started.

Nazi Austria[]

Greater Vienna[]

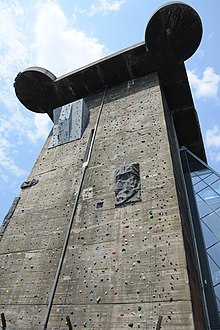

Greater Vienna was the second-largest city of the Reich, three time greater than old Vienna.[5][6] Three pairs of concrete flak towers were constructed between 1942 and 1944, one of them is known as Haus des Meeres, another one Contemporary Art Depot (currently closed).[7]

Linz[]

Linz was one of the Führer cities. Only Nibelungen Bridge was constructed.[8]

Housing construction[]

The Nazis constructed many apartments, 100,000 of them in Berlin alone, mostly as housing estates eg. in Grüne Stadt (Green Town) in Prenzlauer Berg.[9][10][11] Volkswagen's city Wolfsburg was originally constructed by the Nazis.

Proponents[]

- Hermann Bartels

- Peter Behrens

- German Bestelmeyer

- Paul Bonatz

- Woldemar Brinkmann

- Walter Brugmann

- Richard Ermisch

- Gottfried Feder

- Roderich Fick

- Theodor Fischer

- Leonhard Gall

- Hermann Giesler

- Wilhelm Grebe

- Fritz Hoger

- Eugen Honig

- Clemens Klotz

- Wilhelm Kreis

- Werner March

- Konrad Nonn

- Ludwig Ruff

- Franz Ruff

- Ernst Sagebiel

- Paul Schmitthenner

- Julius Schulte-Frohlinde

- Paul Schultze-Naumburg

- Alexander von Senger

- Albert Speer

- Paul Troost

- Rudolf Wolters

Surviving examples of Nazi architecture[]

- The Academy for Youth Leadership in Braunschweig

- The Berchtesgaden Chancellery Branch office in Bischofswiesen

- The new terminal building at Berlin Tempelhof Airport

- The widening of the Charlottenburger Chaussee in Berlin

- The former Reichsbank building in Berlin

- The Führerbau in Munich

- The in Weimar

- The Haus der Kunst in Munich

- The Kehlsteinhaus in Berchtesgaden

- The Ministry of Aviation building in Berlin

- The Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg

- The Olympiastadion in Berlin

- The NS-Ordensburgen Krössinsee, Sonthofen and Vogelsang

- The Prora building complex in Rügen

- The Theater Saarbrücken in Saarbrücken

- The Totenburg Mausoleum in Wałbrzych, Poland

- The Lower Silesian Government Office Building in Wrocław, Poland.

See also[]

- List of Nazi constructions

- Führer Headquarters

- Schwerbelastungskörper

- Urban planning in Nazi Germany

- Totalitarian architecture

- Fascist architecture

- Reactionary modernism

- Völkisch movement

- Führermuseum

References[]

- ^ Nazi architecture, in "Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture", 2006, p. 518.

- ^ Espe, Hartmut (1981). "Differences in the perception of national socialist and classicist architecture". Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1016/s0272-4944(81)80016-3. ISSN 0272-4944.

- ^ "15. Transformer Building and Workers' Housing | General Plan of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds".

- ^ Jaskot, Paul B. (2000). The architecture of oppression: the SS, forced labor and the Nazi monumental building economy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0203169654. OCLC 48137989.

- ^ "Exhibition: »Vienna. The Pearl of the Reich« Planning for Hitler".

- ^ "Vienna under the Nazi-Regime - History of Vienna".

- ^ "Vienna Luftwaffe Anti Aircraft Flak Towers today". 3 November 2017.

- ^ "The "Führer's prerogative" and the planned "Führer Museum" in Linz - Art Database".

- ^ "Der Wohnungsbau der Nazi-Zeit – Unbekanntes Erbe". 28 November 2006.

- ^ http://www.reimer-mann-verlag.de/pdfs/302786_1.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Grüne Stadt | Michail Nelken".

Bibliography[]

- Baynes, Norman H., ed. (1942). The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922–August 1939. Two vols. London: Oxford University Press.

- Brenner, Hildegard (1965). La politica culturale del nazismo [Die Kunstpolitik des Nationalsozialismus (Art policies of Nazism)] (in Italian). Translated from German by Enzo Collotti. Bari: Laterza.

- ; Cowdery, Josephine (2003). The New German Reichschancellery in Berlin 1938–1945. Victory WW2 Publishing. ISBN 978-0910667289.

- De Jaeger, Charles (1981). The Linz file: Hitler's plunder of Europe's art. Exeter: Webb & Bower. ISBN 978-0906671306.

- Dülffer, Jost; Thies, Jochen; Henke, Josef (1978). Hitlers Städte: Baupolitik Im Dritten Reich. Eine Dokumentation [Building Policies in the Third Reich] (in German). Köln: Böhlau. ISBN 3412034770.

- Giesler, Hermann (1977). Ein Anderer Hitler: Bericht Seines Architekten Erlebnisse, Gesprache, Reflexionen [A Different Hitler: Report on its Architects' Experiences, Conversations, Reflections] (in German). Druffel. ISBN 978-3806108200.

- Helmer, Stephen (1985). Hitler's Berlin: The Speer Plans for Reshaping the Central City (Illustrated). Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. ISBN 0835716821.

- Hitler, Adolf (1971). Mein Kampf [My Struggle]. Translated by Ralph Manheim. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0395078013. In Internet Archive (1941 edition by Reynal & Hitchcock, New York).

- Hitler, Adolf (2000). Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944: His Private Conversations. Translated by Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 1929631057.

- Homze, Edward L. (1967). Foreign Labor in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691051186.

- Jaskot, Paul B. (2000). The Architecture of Oppression: The SS, Forced Labor and the Nazi Monumental Building Economy. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415223416.

- Krier, Leon (1989). Albert Speer Architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 2871430063.

- Lärmer, Karl (1975). Autobahnbau in Deutschland 1933 bis 1945 [Highway construction in Germany 1933-1945] (in German). Berlin: Akademie Verlag. ASIN B001UWP0DY.

- Lehmann-Haupt, Hellmut (1973). Art under a Dictatorship (Illustrated). New York: Octagon Books. ISBN 0374948968.

- Lehrer, Steven (2006). The Reich Chancellery and Fuhrerbunker Complex: An Illustrated History of the Seat of the Nazi Regime. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786423934.

- Mittig, Hans-Ernst (2005). "Marmor der Reichskanzlei". In Bingen, Dieter; Hinz, Hans-Martin (eds.). Die Schleifung: Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau historischer Bauten in Deutschland und Polen [The Razing: Destruction and Reconstruction of Historical Buildings in Germany and Poland] (in German). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 3447050969.

- Nerdinger, Winfried (1999). Bauhaus-Moderne im Nationalsozialismus [Modernist Architecture in Nazi Germany] (in German). Prestel. ISBN 978-3791312699.

- Petsch, Joachim (1976). Baukunst Und Stadtplanung Im Dritten Reich: Herleitung, Bestandsaufnahme, Entwicklung, Nachfolge [Architecture and urban planning in the Third Reich: Origin, Inventory, Development, Follow-up] (in German). C. Hanser. ISBN 978-3446122796.

- Rittich, Werner (1938). Architektur und Bauplastik der Gegenwart [Plastic Figures in Modern Architecture] (in German). Berlin: Rembrandt Verlag.

- Schönberger, Angela (1981). Die Neue Reichskanzlei von Albert Speer. Zum Zusammenhang von nationalsozialistischer Ideologie und Architektur [The New Reich Chancellery by Albert Speer. To a Coherence between Nazi Ideology and Architecture] (in German). Berlin: Gebrüder Mann. ISBN 978-3786112631.

- Scobie, Alexander (1990). Hitler's State Architecture: The Impact of Classical Antiquity. College Art Association Monograph – Book 45. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271006918.

- Schmitz, Matthias (1940). A Nation Builds: Contemporary German Architecture. New York: German Library of Information.

- Speer, Albert (1970). Inside the Third Reich. Translation by Richard and Clara Winston. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 002037500X. In Internet Archive.

- Spotts, Frederic (2002). Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. Woodstock, New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 1585673455.

- Taylor, Robert (1974). The Word in Stone: The Role of Architecture in the National Socialist Ideology. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520021932.

- Thies, Jochen (1976). Architekt der Weltherrschaft. Die Endziele Hitlers [Architect of world domination. The ultimate goals of Hitler] (in German). Düsseldorf: Droste. ISBN 978-3770004256.

- Zoller, Albert (1949). Hitler privat. Erlebnisbericht seiner Geheimsekretärin [Hitler's Private Secretary Testimony] (in German). Düsseldorf: Droste. ASIN B0023S7QZO.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nazi architecture. |

- A Theory of Ruin-value , Cornelius Holtorf, last updated on 21 December 2004.

- A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust website:

- NS-Architektur at LEMO – Lebendiges Museum Online.

- Nazi architecture

- Architectural styles

- History of Berlin

- Culture in Berlin