Unstoppable (2010 film)

| Unstoppable | |

|---|---|

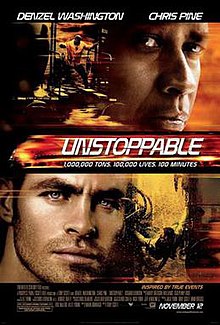

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tony Scott |

| Written by | Mark Bomback |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ben Seresin |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Harry Gregson-Williams |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States[3][2][4] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $85–100 million[5][6][7] |

| Box office | $167.8 million[7] |

Unstoppable is a 2010 American action thriller film directed and produced by Tony Scott and starring Denzel Washington and Chris Pine. It is based on the real-life CSX 8888 incident, telling the story of a runaway freight train and the two men who attempt to stop it. It was the last film Tony Scott directed before his death.

The film was released in the United States and Canada on November 12, 2010. It received generally positive reviews from critics and grossed $167 million against a production budget between $85–100 million. It was nominated for an Oscar for Best Sound Editing at the 83rd Academy Awards, but lost to Inception.

Plot[]

While two yard hostlers are moving an Allegheny and West Virginia Railroad (AWVR) train, pulled by lead locomotive #777 at Fuller Yard in northern Pennsylvania, Dewey, the engineer of the mixed-freight train, realizes that a trailing-point switch is not correctly aligned and leaves the cab of the moving locomotive after setting the throttle to idle. As he moves the switch, the throttle pops out of idle into full throttle notch 8. Dewey attempts to get back on the now-accelerating lead locomotive but is dragged and falls, leaving the train unattended going south down the mainline.

Believing the train is coasting, yardmaster Connie Hooper orders lead welder Ned Oldham to get ahead of the train in his pickup truck and switch it off the main track, but when Oldham finds that the train has already passed where it was expected to be, they realize it is running on full power. Connie alerts Oscar Galvin, VP of Train Operations, and contacts local, county, and state police, asking them to block all level crossings, while Ned continues to chase 777 in his truck. Federal Railroad Administration inspector Scott Werner, while visiting Fuller Yard to meet with the Railroad Safety Campaign excursion train (RSC 2002), warns that eight of the 39 cars contain highly toxic and flammable molten phenol, which would cause a major disaster if the train should derail in a populated area. News of the runaway soon draws ongoing media coverage.

Connie suggests they purposely derail the train while it passes through unpopulated farmland. Galvin dismisses her opinion, believing he can save the company money by lashing the train behind two locomotives helmed by engineer Judd Stewart, slowing it down enough for employee and former U.S. Marine Ryan Scott to descend via helicopter to the control cab of 777. However, Ryan is knocked unconscious during the attempt when 777 suddenly lunges at Stewart's lash-up as he touches down, sending him crashing into trailing runaway locomotive 767's windshield, and when Stewart attempts to divert 777 to a siding, he is unable to slow it down and is killed when his locomotives derail at a switch and the diesel fuel ignites and explodes, engulfing the lash-up diesels in a huge fireball. Realizing that 777 will derail on the Stanton Curve, a tight, elevated portion of track in the heavily populated Southern Pennsylvania town of Stanton, plans are finally made to purposely derail the train just north of the smaller town of Arklow.

Meanwhile, veteran AWVR railroad engineer Frank Barnes and conductor Will Colson, a new hire preoccupied with a restraining order from his wife Darcy, are pulling 25 cars with locomotive #1206 on the same line going north out of Brewster Yard in Southern Pennsylvania. Ordered onto a siding off the mainline, they narrowly manage to pull into a RIP track before 777 races by, smashing through their last boxcar. Frank observes that 777's last car has an open coupler and proposes that they travel in reverse and attempt to couple their engine to the runaway, then use their own brakes to slow down 777 before it reaches the Stanton Curve. Will uncouples 1206 from their own cars, while Frank reports his plan to Connie and Galvin, warning that Galvin's idea of using portable derailers will not work given 777's momentum. Galvin threatens to fire Frank, who informs Galvin that he has already received a forced, half-benefits, early-retirement notice. Galvin threatens to fire Will as well, but both Frank and Will ignore him and pursue 777.

As 777 approaches the portable derailers, police first attempt to engage the engine's fuel cutoff button by shooting at it, but are unsuccessful and some mistakenly shoot the larger fuel cap instead. As Frank predicted, the train barrels through the derailers unhindered, to Galvin's dumbfounded disbelief and horror. Knowing that Frank's plan is their only remaining chance at preventing a cataclysmic disaster, Connie and Werner fully support him and take over control of the situation from Galvin. Meanwhile, Darcy learns about 777 and Will's involvement in the chase. Similarly, Frank's daughters learn of their father's involvement while at work.

Frank and Will catch up to 777's trailing hopper car and attempt to engage the coupler, accidentally blowing the seal on the car and spraying grain onto 1206. When the locking pin will not engage, Will kicks it into place, but his foot gets crushed in the process. Will hobbles back to 1206's cab, and Frank tries to slow 777 with the independent brakes, but 777's momentum proves to be too powerful. Will stays in the cab to work the dynamic brakes and throttle while Frank works his way along the top of 777's cars in a risky attempt to engage the handbrakes on each car. Eventually, 1206's brakes burn out due to the traction motors being overworked and the train starts gaining speed again. Using the independent air brake, Will coordinates the brake timing with Frank, and they manage to reduce speed enough to clear the Stanton Curve, just barely, with the train tipping but righting itself. As 777 picks up speed, Frank finds his path to 777's cab blocked. Ned arrives in his truck with a police escort on a road parallel to the tracks. Will jumps onto the bed of Ned's truck, and Ned races to the front of 777, where Will leaps onto the locomotive, reduces the throttle to idle, and applies the brakes, finally allowing them to bring the runaway train to a safe stop. Ned and first responders pull up next to the now stopped 777, and Will's injured foot is treated by the paramedics. Darcy and Will's son arrive and reunite with him. Connie arrives shortly thereafter to congratulate them and Ned for their efforts while Ned is handling the press conference with another AWVR representative, surrounded by friends, family, and vehicles from first responders and news outlets.

Frank, Will, and Ned are hailed as heroes. Before the closing credits, it is revealed that Frank was promoted and later retires with full benefits. Will is happily married to Darcy (who is currently expecting their second child), recovers from his injuries, and continues working with AWVR. Connie is promoted to Galvin's VP position, while it's implied that Galvin was fired for both his poor handling of the incident and causing Stewart's death. Ryan Scott recovers from his injuries, and Dewey, who is held responsible for causing the situation, is fired from his job and goes on to work in the fast-food industry.

Cast[]

- Denzel Washington as Frank Barnes, a veteran railroad engineer.

- Chris Pine as Will Colson, a young train conductor.

- Rosario Dawson as Connie Hooper, the yardmaster of Fuller Yard.

- Ethan Suplee as Dewey, a hostler who accidentally instigates the disaster.

- Kevin Dunn as Oscar Galvin, vice-president of AWVR train operations.

- Kevin Corrigan as Inspector Scott Werner, an FRA inspector who helps Frank, Will, and Connie.

- Kevin Chapman as Bunny, a railroad operations dispatcher for Fuller Yard.

- Lew Temple as Ned Oldham, a railroad lead welder.

- T. J. Miller as Gilleece, Dewey's conductor, also a hostler.

- Jessy Schram as Darcy Colson, Will's estranged wife.

- David Warshofsky as Judd Stewart, a veteran engineer who is friends with Frank & dies in an attempt to slow the runaway train.

- Andy Umberger as Janeway, the president of AWVR.

- Elizabeth Mathis and Meagan Tandy as Nicole and Maya Barnes, Frank's daughters who work as waitresses at Hooters.

- Aisha Hinds as Casey Barnes, a Railroad Safety Campaign coordinator in an excursion train to Fuller Yard for a field trip designed to teach schoolchildren about railroad safety.

- Ryan Ahern as Ryan Scott, a railway employee and US Marine veteran of the war in Afghanistan who is injured in an attempt to stop the runaway.

- Jeff Wincott as Jesse Colson, Will's brother whom Will is living with at the start of the film.

Locomotives[]

The locomotives used in the movie were borrowed from two railroads. The two runaway AWVR locomotives, 777 and 767, were GE AC4400CWs borrowed from the Canadian Pacific Railway. 777 was played by CP 9777 and 9782. 767 was played by CP 9758 and 9751. The EMD SD40-2s which played AWVR 1206, 7375, 5624, 7346, 5607, and 5580 were all borrowed from Wheeling and Lake Erie. 1206 was played by W&LE 6353 and 6354. 7375 and 5624 were played by W&LE 6352. Lastly, 7346, 5607 (Brewster Yard), and 5580 were played by W&LE 6351.[8][9]

| Locomotive type | Real life owner | Real life numberboards | Featured |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC4400CW | CP | CP 9777[10] & 9782[11] | AWVR 777 |

| CP 9758[12] & 9751[13] | AWVR 767 | ||

| EMD SD40-2 | W&LE | W&LE 6353[14] & 6354[15] | AWVR 1206 |

| W&LE 6352[16] | AWVR 7375 & 5624 | ||

| W&LE 6351[17] | AWVR 7346, 5607, & 5580 | ||

| EMD GP11 | SWP | SWP 2002[18] | RSC 2002 |

Production[]

Unstoppable suffered various production challenges before filming could commence, including casting, schedule, location, and budgetary concerns.[19][20]

In August 2004, Mark Bomback was hired by 20th Century Fox to write the screenplay Runaway Train.[21] Robert Schwentke signed on to direct Runaway Train in August 2005, with plans to begin shooting in early 2006.[22] In June 2007, Martin Campbell was in negotiations to replace Schwentke as director of the film, now titled Unstoppable.[23][24] Campbell was attached until March 2009, when Tony Scott came on board as director.[25] In April, both Denzel Washington and Chris Pine were attached to the project.[26]

The original budget had been trimmed from $107 million to $100 million, but Fox wanted to reduce it to the low $90 million range, asking Scott to cut his salary from $9 million to $6 million and wanting Washington to shave $4 million off his $20 million fee.[27] Washington declined and, although attached since April,[28] formally withdrew from the project in July, citing lost patience with the film's lack of a start date.[20] Fox made a modified offer as enticement, and he returned to the project two weeks later.[28][29][30]

Production was headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the fictional "Allegheny and West Virginia Railroad" depicted in the movie is headquartered. Filming took place in a broad area around there including the Ohio cities of Martins Ferry, Bellaire, Mingo Junction, Steubenville, and Brewster,[31] and in the Pennsylvania cities of Pittsburgh,[32] Emporium, Milesburg, Tyrone, Julian, Unionville, Port Matilda, Bradford, Monaca, Eldred, Mill Hall, Turtlepoint, Port Allegany, and Carnegie,[33] and also in Portville, New York and Olean, New York.[34] The film is the most expensive ever to be shot in Western Pennsylvania.[35]

The Western New York and Pennsylvania Railroad's Buffalo Line was used for two months during daylight, while the railroad ran its regular freight service at night.[36] The real-life bridge and elevated curve in the climactic scene is the B & O Railroad Viaduct between Bellaire, Ohio and Benwood, West Virginia.[37]

A two-day filming session took place at the Hooters restaurant in Wilkins Township, a Pittsburgh suburb, featuring 10 Hooters Girls from across the United States. Other interior scenes were shot at 31st Street Studios (then the Mogul Media Studios) on 31st Street in Pittsburgh. Principal photography began on August 31, 2009,[38] for a release on November 12, 2010.

Filming was delayed for one day when part of the train accidentally derailed on November 21, 2009.[39]

The locomotives used on the runaway train, 777 and trailing unit 767, were played by GE AC4400CWs leased from the Canadian Pacific Railway. CP #9777 and #9758 played 777 and 767 in early scenes, and CP #9782 and #9751 were given a damaged look for later scenes.[40] These four locomotives were repainted to standard colors in early 2010 by Canadian Pacific following the filming, but the black and yellow warning stripes from the AWVR livery painted on the plows of each locomotive were left untouched (except for 9777's plow) and remained visible on the locomotives. The plows on 9782 and 9751 appear to have been repainted black as of 2018 and 2020 respectively.[41][42]

Most of the other AWVR locomotives seen in the film, including chase locomotive #1206, and the locomotive consist used in an attempt to stop the train, #7375 and #7346, were played by EMD SD40-2s leased from the Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway. #1206 was played by three different SD40-2s: W&LE #6353 and #6354, and a third unit that was bought from scrap and modified for cab shots. #6353 and #6354 were returned to the W&LE and painted black to resume service, but #6354's windshield remains jutted forward from the AWVR livery.[15] Judd Stewart's locomotive consist #7375 and #7346 were played by W&LE #6352 and #6351, which also played two locomotive "extras" (#5624 and #5580), wearing the same grey livery with different running numbers.[40] The Railroad Safety Campaign excursion train locomotive (RSC #2002) was played by a Southwest Pennsylvania Railroad Paducah-built EMD GP11 rebuilt from an EMD GP9. The two passenger coaches carrying schoolchildren were provided by the Orrville Railroad Heritage Society in Orrville, Ohio.[43]

Inspiration[]

Unstoppable was inspired by the 2001 CSX 8888 incident, in which a runaway train ultimately traveled 66 miles (106 km) through northwest Ohio. Led by CSX Transportation SD40-2 #8888, the train left Stanley Yard in Walbridge, Ohio with no one at the controls, after the hostler got out of the slow-moving train to correct a misaligned switch, mistakenly believing he had properly set the train's dynamic braking system, much as his counterpart (Dewey) in the film mistakenly believed he had properly set the locomotive's throttle (in the CSX incident, the locomotive had an older-style throttle stand where the same lever controlled both the throttle and the dynamic brakes; in fact, putting on "full throttle" and "full brakes" both involved advancing the same lever to the highest position after switching to a different operating mode. Thus if the engineer failed to properly switch modes, it was easy to accidentally apply full throttle instead of full brake, or vice-versa.)

Two of the train's tank cars contained thousands of gallons of molten phenol, a toxic ingredient used in glues, paints, and dyes. The chemical is very dangerous; it is highly corrosive to the skin, eyes, lungs, and nasal tract. Attempts to derail it using a portable derailer failed, and police had tried to engage the red fuel cutoff button by shooting at it; after having three shots mistakenly hit the red fuel cap, this ultimately had no effect because the button must be pressed for several seconds before the engine would be starved of fuel and shut down. For two hours, the train traveled at speeds up to 51 miles per hour (82 km/h) until the crew of a second locomotive, CSX #8392, coupled onto the runaway and slowly applied its brakes. Once the runaway was slowed down to 11 miles per hour (18 km/h), CSX trainmaster Jon Hosfeld ran alongside the train, and climbed aboard, shutting down the locomotive. The train was stopped at the Route 31 crossing, just south-southeast of Kenton, Ohio. No one was seriously injured in the incident.[44]

RSC 2002 was inspired by a CSX Operation Lifesaver passenger train, which was turning around at Stanley Yard and was preparing to head back south after having traveled north from Columbus to Walbridge using the same track CSX 8888 was now on. CSX ended up having to bus the safety train's 120 passengers back to the cities at which they had boarded, including Bowling Green, Findlay, and Kenton.[45]

When the film was released, the Toledo Blade compared the events of the film to the real-life incident. "It's predictably exaggerated and dramatized to make it more entertaining," wrote David Patch, "but close enough to the real thing to support the 'Inspired by True Events' announcement that flashes across the screen at its start." He notes that the dead man switch would probably have worked in real life despite the unconnected brake hoses, unless the locomotive, or independent brakes, were already applied. As explained in the movie, the dead man's switch failed because the only available brakes were the independent brakes, which were quickly worn through, similar to CSX 8888. The film exaggerates the possible damage the phenol could have caused in a fire, and he found it incredible that the fictional AWVR freely disseminated information such as employees' names and images and the cause of the runaway to the media. In the real instance, he writes, the cause of the runaway was not disclosed until months later when the National Transportation Safety Board released its report, and CSX never made public the name of the engineer whose error caused the runaway, nor what disciplinary action was taken.[46]

Soundtrack[]

The film score was composed by Harry Gregson-Williams and the soundtrack album was released on December 7, 2010.

Release[]

Marketing[]

A trailer was released online on August 6, 2010.[47] The film went on general release on November 12, 2010.

Home media[]

Unstoppable was released on DVD and Blu-ray on February 15, 2011.[48]

Reception[]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 87% certified fresh based on 193 reviews, with an average rating of 6.92/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "As fast, loud, and relentless as the train at the center of the story, Unstoppable is perfect popcorn entertainment—and director Tony Scott's best movie in years."[49] Metacritic gives the film a weighted average score of 69 out of 100, based on 32 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[50]

Film critic Roger Ebert rated the film three and a half stars out of four, remarking in his review, "In terms of sheer craftsmanship, this is a superb film."[51] In The New York Times, Manohla Dargis praised the film's visual style, saying that Scott "creates an unexpectedly rich world of chugging, rushing trains slicing across equally beautiful industrial and natural landscapes."[52]

The Globe and Mail in Toronto was more measured. While the film's action scenes "have the greasy punch of a three-minute heavy-metal guitar solo", its critic felt the characters were weak. It called the film "an opportunistic political allegory about an economy that's out of control and industries that are weakened by layoffs, under-staffing, and corporate callousness."[53]

Director Quentin Tarantino highlighted the film in a January 2020 episode of the Rewatchables podcast, and included it in his list of the ten best of the decade.[54] In June 2021, he named it one of his favorite "Director's Final Films".[55] Christopher Nolan cited the film as an influence, praising its use of suspense.[56]

Box office[]

Unstoppable was expected to take in about the same amount of money as the previous year's The Taking of Pelham 123, another Tony Scott film involving an out-of-control train starring Denzel Washington. Pelham took in $23.4 million during its opening weekend in the United States and Canada.[5] Unstoppable had a strong opening night on Friday November 12, 2010, coming in ahead of Megamind with a gross of $8.1 million. However, Megamind won the weekend, earning $30 million to Unstoppable's $23.9 million.[57] Unstoppable performed slightly better than The Taking of Pelham 123 did in its opening weekend. As of April 2011, the film had earned $167,805,466 worldwide.[7][58]

Awards[]

The film was nominated in the Best Sound Editing (Mark Stoeckinger) category at the 83rd Academy Awards and nominated for Teen Choice Award for Choice Movie – Action.[59][60]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Unstoppable – Production Credits". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2008. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "AFI|Catalog - Unstoppable". catalog.afi.com. American Film Institute. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Film: Unstoppable". lumiere.obs.coe.int.

- ^ ""Unstoppable": Denzel wrestles runaway train, saves American manhood". Salon.com. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Movie Projector: 'Unstoppable' seeks to derail 'Megamind' as 'Morning Glory' looks dim". Los Angeles Times. November 11, 2010.

One person close to the production said "Unstoppable" cost about $100 million after the benefit of tax credits, though another person close to Fox said the final budget was closer to $85 million.

- ^ "Unstoppable – Box Office Data, Movie News, Cast Information". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Unstoppable (2010)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "UNSTOPPABLE! The Trains of the Hit Movie and the event that inspired the movie!". The CineTrains Project - Trains in the Cinema and TV. January 6, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "NS 043-06 with the Unstoppable Train". YouTube. November 2, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "CP 9777". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "CP 9782". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "CP 9758". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "CP 9751". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "WE 6353". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "WE 6354 and 6985". www.rrpicturearchives.net. May 10, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "WE 6352". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "WE 6351". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "SWP 2002, NREX 8749, SWP 2003 (1)". www.rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (June 30, 2009). "Action pic "Unstoppable" hits budget snags". The Hollywood Reporter. Reuters. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fleming, Michael (July 13, 2009). "Denzel Washington exits 'Unstoppable'". Variety. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (August 16, 2004). "Bomback hops aboard Fox pic". Variety. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ Brodesser, Claude (August 21, 2005). "'Train' meets its maker". Variety. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (June 7, 2007). "Fox dealing with 'Unstoppable' budget". Variety. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Sampson, Mike (June 8, 2007). "Campbell is Unstoppable". JoBlo.com. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (March 27, 2009). "Tony Scott boards 'Unstoppable'". Variety. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (June 29, 2009). "Fox train thriller just 'Unstoppable'". Variety. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ "Denzel Washington Drops Out of Unstoppable?". ComingSoon.com. July 14, 2009. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Parsons, Ryan (July 23, 2009). "Denzel Washington Unstoppable Again". CanMag.com. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (July 22, 2009). "Washington back on track with Fox". Variety. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Goldstein, Patrick (August 5, 2009). "In the salary tug of war between studios and talent, it's no contest". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Heldenfels, Rich (November 7, 2010). "Ohio is stunt double". Akron Beacon Journal. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ^ Vancheri, Barbara (July 24, 2009). "Action flick 'Unstoppable' to film in Pittsburgh". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ "Denzel Washington movie call takes job fair tone". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. August 27, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Postles, Don (September 10, 2009). "Hollywood comes to Olean Friday". WIVB.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ Loeffler, William (November 7, 2010). "'Unstoppable' most expensive film shot in Western Pennsylvania". TribLIVE.com. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ Zimmermann, Karl (2012). "Where Alcos Tough It Out". Trains. Kalmbach Publishing. 72 (6): 44.

- ^ Vancheri, Barbara (November 12, 2010). "'Unstoppable' director Tony Scott loved filming in Pennsylvania". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Block Communications. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Gayle Fee & Laura Raposa (August 17, 2009). "We Hear: Kevin Chapman, Denzel Washington, Tom Werner & more..." Boston Herald.

- ^ "Train Derails in Bridgeport, Not Part of Movie". WTRF.com. November 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The AWVR engines used in the movie Unstoppable". myrailfan.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011.

- ^ "CP 9782". www.rrpicturearchives.net. September 30, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "Mid train DPU CP 9751". www.rrpicturearchives.net. September 6, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Locher, Paul (November 14, 2010). "Trains featured in movie starring Denzel Washington". The-Daily-Record.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ "CSX 8888 – The Final Report". Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ Feehan, Jennifer; Lecker, Kelly (May 16, 2001). "Disaster avoided during hours of panic, 66 miles of terror". The Blade. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Patch, David (November 12, 2010). "Hollywood widens truth gauge in runaway train flick". Toledo Blade. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ Rosenberg, Adam (June 8, 2010). "'Unstoppable' Trailer Rolling Like An Out-Of-Control Freight Train". MTV Movie Blog. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ^ "Unstoppable (2010)". VideoETA. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ "Unstoppable (2010)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ^ "Unstoppable Reviews, Ratings, Credits". Metacritic. CBS.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 10, 2010). "Unstoppable". Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (November 11, 2010). "I Think I Can: Trying to Stop a Crazy Train Hurtling to Disaster". The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ "Unstoppable: Like derivatives trading, this train is out of control". The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Canada: CTVGlobeMedia. November 12, 2010. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino Says Tony Scott's 'Unstoppable' Is One Of His Top 10 Films Of The Last Decade". theplaylist.net.

- ^ "Final Films with Quentin Tarantino".

- ^ Earl, William (May 25, 2017). "Christopher Nolan Reveals How 11 Classic Films Inspired 'Dunkirk'". IndieWire.

- ^ "Box office: No. 1 'Megamind' stops 'Unstoppable'". Los Angeles Times. November 14, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Gray, Brandon (November 13, 2010). "Friday Report: 'Unstoppable' Squeaks by 'Megamind'". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ "Oscar nominations 2011 in full". BBC News. January 25, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ "Blake Lively Wins Choice TV Drama Actress The Teen Choice Awards! Here Are More Winners!". Hollywood Life. August 7, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Unstoppable (2010 film) |

- 2010 films

- English-language films

- 2010 action thriller films

- 2010s disaster films

- 2010s survival films

- 20th Century Fox films

- American films

- American films based on actual events

- American action thriller films

- American disaster films

- American survival films

- CSX Transportation

- Disaster films based on actual events

- Dune Entertainment films

- Films about railway accidents and incidents

- Films about the United States Marine Corps

- Films directed by Tony Scott

- Films scored by Harry Gregson-Williams

- Films set in 2010

- Films set in Pennsylvania

- Films set in Pittsburgh

- Films set on trains

- Films shot in New York (state)

- Films shot in Ohio

- Films shot in Pennsylvania

- Films shot in Pittsburgh

- Films with screenplays by Mark Bomback

- Scott Free Productions films

- Techno-thriller films

- Thriller films based on actual events