V404 Cygni

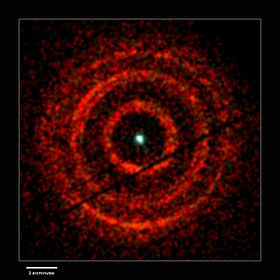

X-ray light echoes from the 2015 nova eruption Credit: Andrew Beardmore (Univ. of Leicester) and NASA/Swift | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Cygnus |

| Right ascension | 20h 24m 03.83s[1] |

| Declination | +33° 52′ 02.2″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 11.2 - 18.8[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | K3 III[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.3[4] |

| B−V color index | +1.5[4] |

| Variable type | Nova[5] |

| Astrometry | |

| Distance | 2,390[6] pc |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | +3.4[7] |

| Details | |

| A (black hole) | |

| Mass | 9[6] M☉ |

| B | |

| Mass | 0.7[7] M☉ |

| Radius | 6.0[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 10.2[7] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 3.50[8] cgs |

| Temperature | 4,800[8] K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 36.4[8] km/s |

| Other designations | |

V404 Cyg, Nova Cygni 1938, Nova Cygni 1989, GS 2023+338, AAVSO 2020+33 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

V404 Cygni is a microquasar and a binary system in the constellation of Cygnus. It contains a black hole with a mass of about 9 M☉ and an early K giant star companion with a mass slightly smaller than the Sun. The star and the black hole orbit each other every 6.47129 days at fairly close range. Due to their proximity and the intense gravity of the black hole, the companion star loses mass to an accretion disk around the black hole and ultimately to the black hole itself.[9] The "V" in the name indicates that it is a variable star, which repeatedly gets brighter and fainter over time. It is also considered a nova, because at least three times in the 20th century it produced a bright outburst of energy. Finally, it is a soft X-ray transient because it periodically emits short bursts of X-rays.

In 2009, the black hole in the V404 Cygni system became the first black hole to have an accurate parallax measurement for its distance from the Solar System. Measured by very-long-baseline interferometry using the High Sensitivity Array, the distance is 2.39±0.14 kiloparsecs,[10] or 7800±460 light-years.

In April 2019, astronomers announced that jets of particles shooting from the black hole were wobbling back and forth on the order of a few minutes, something that had never before been seen in the particle jets streaming from a black hole. Astronomers believe that the wobble is caused by the Lense-Thirring effect due to warping of space/time by the huge gravitational field in the vicinity of the black hole.[11]

The black hole companion has been proposed as a Q star candidate.[12]

Discovery[]

This system was first noted as Nova Cygni 1938 and given the variable star designation V404 Cygni. It was considered to be an ordinary "moderately fast" nova although large fluctuations were noted during the decline. It was discovered after maximum light, and the photographic magnitude range was measured at 12.5–20.5.[13]

On May 22, 1989 the Japanese Ginga Team discovered a new X-ray source that was catalogued as GS 2023+338.[14] This source was quickly linked to V404 Cygni, which was discovered to be in outburst again as Nova Cygni 1989.[15][16]

Follow-up studies showed a previously unnoticed outburst in 1956. There was also a possible brightening in 1979.[17]

2015 outburst[]

On 15 June 2015 NASA's Swift satellite detected the first signs of renewed activity. A worldwide observing campaign was commenced and on 17 June ESA's INTEGRAL Gamma-ray observatory started monitoring the outburst. INTEGRAL was detecting "repeated bright flashes of light time scales shorter than an hour, something rarely seen in other black hole systems", and during these flashes V404 Cygni was the brightest object in the X-ray sky—up to fifty times brighter than the Crab Nebula. This outburst was the first since 1989. Other outbursts occurred in 1938 and 1956, and the outbursts were probably caused by material piling up in a disk around the black hole until a tipping point was reached.[20] The outburst was unusual in that physical processes in the inner accretion disk were detectable in optical photometry from small telescopes; previously, these variations were thought to be only detectable with space-based X-ray telescopes.[9] A detailed analysis of the INTEGRAL data revealed the existence of so-called near the black hole. This plasma consists of electrons and their antimatter counterparts, positrons.[21]

A follow-up study of the 2015 data found a coronal magnetic field strength of 461 ± 12 gauss, "substantially lower than previous estimates for such systems".[22]

See also[]

- List of stars in Cygnus

- List of black holes

- List of nearest black holes

References[]

- ^ a b Cutri, Roc M.; Skrutskie, Michael F.; Van Dyk, Schuyler D.; Beichman, Charles A.; Carpenter, John M.; Chester, Thomas; Cambresy, Laurent; Evans, Tracey E.; Fowler, John W.; Gizis, John E.; Howard, Elizabeth V.; Huchra, John P.; Jarrett, Thomas H.; Kopan, Eugene L.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Light, Robert M.; Marsh, Kenneth A.; McCallon, Howard L.; Schneider, Stephen E.; Stiening, Rae; Sykes, Matthew J.; Weinberg, Martin D.; Wheaton, William A.; Wheelock, Sherry L.; Zacarias, N. (2003). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: 2MASS All-Sky Catalog of Point Sources (Cutri+ 2003)". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. 2246: II/246. Bibcode:2003yCat.2246....0C.

- ^ Watson, C. L. (2006). "The International Variable Star Index (VSX)". The Society for Astronomical Sciences 25th Annual Symposium on Telescope Science. Held May 23–25. 25: 47. Bibcode:2006SASS...25...47W.

- ^ Khargharia, Juthika; Froning, Cynthia S.; Robinson, Edward L. (2010). "Near-infrared Spectroscopy of Low-mass X-ray Binaries: Accretion Disk Contamination and Compact Object Mass Determination in V404 Cyg and Cen X-4". The Astrophysical Journal. 716 (2): 1105. arXiv:1004.5358. Bibcode:2010ApJ...716.1105K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/716/2/1105. S2CID 119116307.

- ^ a b Liu, Q. Z.; Van Paradijs, J.; Van Den Heuvel, E. P. J. (2007). "A catalogue of low-mass X-ray binaries in the Galaxy, LMC, and SMC (Fourth edition)". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 469 (2): 807. arXiv:0707.0544. Bibcode:2007A&A...469..807L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077303. S2CID 14673570.

- ^ Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/GCVS. Originally Published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- ^ a b Bernardini, F.; Russell, D. M.; Shaw, A. W.; Lewis, F.; Charles, P. A.; Koljonen, K. I. I.; Lasota, J. P.; Casares, J. (2016). "Events leading up to the 2015 June Outburst of V404 Cyg". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 818 (1): L5. arXiv:1601.04550. Bibcode:2016ApJ...818L...5B. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/818/1/L5. S2CID 119251825.

- ^ a b c d Shahbaz, T.; Ringwald, F. A.; Bunn, J. C.; Naylor, T.; Charles, P. A.; Casares, J. (1994). "The mass of the black hole in V404 Cygni". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 271: L10–L14. Bibcode:1994MNRAS.271L..10S. doi:10.1093/mnras/271.1.L10.

- ^ a b c González Hernández, Jonay I.; Casares, Jorge; Rebolo, Rafael; Israelian, Garik; Filippenko, Alexei V.; Chornock, Ryan (2011). "Chemical Abundances of the Secondary Star in the Black Hole X-Ray Binary V404 Cygni". The Astrophysical Journal. 738 (1): 95. arXiv:1106.4278. Bibcode:2011ApJ...738...95G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/738/1/95. S2CID 118443418.

- ^ a b Kimura, Mariko; et al. (7 January 2016). "Repetitive patterns in rapid optical variations in the nearby black-hole binary V404 Cygni". Nature. 529 (7584): 54–70. arXiv:1607.06195. Bibcode:2016Natur.529...54K. doi:10.1038/nature16452. PMID 26738590. S2CID 4463697.

- ^ Miller-Jones, J. A. C.; Jonker; Dhawan (2009). "The first accurate parallax distance to a black hole". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 706 (2): L230. arXiv:0910.5253. Bibcode:2009ApJ...706L.230M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/706/2/L230. S2CID 17750440.

- ^ "This Black Hole's Jets Wobble Like Crazy Because It's Warping Space-Time". Space.com. 29 April 2019.

- ^ Brecher, K. (1993-05-01). "Gray Holes". American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts #182. 182: 55.07. Bibcode:1993AAS...182.5507B.

- ^ Duerbeck, Hilmar W (1987). "A reference catalogue and atlas of galactic novae". Space Science Reviews. 45 (1–2): 1. Bibcode:1987SSRv...45....1D. doi:10.1007/BF00187826. S2CID 115854775.

- ^ Kitamoto, Shunji; Tsunemi, Hiroshi; Miyamoto, Sigenori; Yamashita, Koujun; Mizobuchi, Seiko; Nakagawa, Michio; Dotani, Tadayasu; Makino, Fumiaki (1989). "GS2023 + 338 - A new class of X-ray transient source?". Nature. 342 (6249): 518. Bibcode:1989Natur.342..518K. doi:10.1038/342518a0. S2CID 4308343.

- ^ Hurst, G. M (1989). "Nova Cygni 1938 Reappears - V404-CYGNI". Journal of the British Astronomical Society. 99: 161. Bibcode:1989JBAA...99..161H.

- ^ R. M. Wagner; S. Starrfield; A. Cassatella; R. Gonzalez-Riestra; T. J. Kreidl; S. B. Howell; R. M. Hjellming; X.-H. Han; G. Sonneborn (24 July 2005). "The 1989 outburst of V404 cygni: A very unusual x-ray nova". In A. Cassatella; R. Viotti (eds.). Physics of Classical Novae. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 369. pp. 429–430. Bibcode:1990LNP...369..429W. doi:10.1007/3-540-53500-4_162. ISBN 978-3-540-53500-3.

- ^ Richter, Gerold A (1989). "V404 Cyg - a Further Outburst in 1956". Information Bulletin on Variable Stars. 3362: 1. Bibcode:1989IBVS.3362....1R.

- ^ Rodriguez, J.; Cadolle Bel, M.; Alfonso-Garzón, J.; Siegert, T.; Zhang, X. L.; Grinberg, V.; Savchenko, V.; Tomsick, J. A.; Chenevez, J.; Clavel, M.; Diehl, R.; Domingo, A.; Gouiffès, C.; Greiner, J.; Krause, M. G. H.; Laurent, P.; Loh, A.; Markoff, S.; Mas-Hesse, J. M.; Miller-Jones, J. C. A.; Russell, D. M.; Wilms, J. (September 2015). "Correlated optical, X-ray, and γ-ray flaring activity seen with INTEGRAL during the 2015 outburst of V404 Cygni". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 581. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527043. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Martí, Josep; Luque-Escamilla, Pedro L.; García-Hernández, María T. (February 2016). "Multi-colour optical photometry of V404 Cygni in outburst (Research Note)". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 586. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527239. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Monster Black Hole Wakes Up After 26 Years". integral. ESA. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Gamma rays reveal pair plasma from a flaring black hole binary system". Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics. 29 February 2016.

- ^ Yigit Dallilar; et al. (8 Dec 2017). "A precise measurement of the magnetic field in the corona of the black hole binary V404 Cygni". Science. 358 (6368): 1299–1302. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1299D. doi:10.1126/science.aan0249. PMID 29217570.

- Cygnus (constellation)

- X-ray binaries

- Stellar black holes

- Objects with variable star designations

- K-type giants

- Novae

- Recurrent novae