Vibraphone

| |

| Percussion instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vibes, Vibraharp, Vibraceleste |

| Classification | Percussion |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 111.222 (Directly struck idiophone) |

| Inventor(s) | Henry Schluter |

| Developed | 1927 |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Marimba, xylophone, glockenspiel | |

| Musicians | |

| Gary Burton, Lionel Hampton, Ruth Underwood, Stefon Harris, Bobby Hutcherson, Milt Jackson, Mike Freeman, Joe Locke, Steve Nelson, Pascal Schumacher, Dave Samuels, Mark Sherman, Cal Tjader, Tommy Vig, Warren Wolf, Roy Ayers, Manu Dibango, David Friedman | |

| Builders | |

| Musser, Yamaha, Adams Musical Instruments, Saito, Marimba One | |

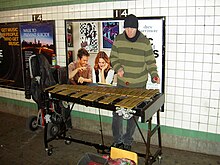

The vibraphone is a musical instrument in the struck idiophone subfamily of the percussion family. It consists of tuned metal bars and is usually played by holding two or four soft mallets and striking the bars. A person who plays the vibraphone is called a vibraphonist, vibraharpist, or vibist.[1]

The vibraphone resembles the marimbaphone and steel marimba, which it superseded.[2] One of the main differences between the vibraphone and other keyboard percussion instruments is that each bar suspends over a resonator tube with a motor-driven butterfly valve at the top. The valves connect together on a common axle, which produces a tremolo or vibrato effect while the motor rotates the axle. The vibraphone also has a sustain pedal similar to a piano. With the pedal up, the bars produce a muted sound. With the pedal down, the bars sustain for several seconds, or until muted with the pedal.

The vibraphone is commonly used in jazz music, in which it often plays a featured role and was a defining element of the sound of mid-20th-century "Tiki lounge" exotica, as popularized by Arthur Lyman. It is the second most popular solo keyboard percussion instrument in classical music, after the marimba, and it is part of the standard college-level percussion performance education. It is a standard instrument in the modern percussion section for orchestras, concert bands, and marching bands (as part of the front ensemble).[3][4]

History[]

Around 1916, instrument maker Herman Winterhoff, of the Leedy Manufacturing Company, began experimenting with "vox humana" effects on a three octave (F-F) steel marimba.[5][6] By attaching a motor, he could create vibrato effects, hence the name "vibraphone". This instrument was marketed by the Leedy Manufacturing Company in the United States starting in 1924.[7] However, this instrument differed significantly from the instrument now called the vibraphone. The Leedy vibraphone did not have a pedal mechanism and had bars made of steel rather than aluminum. The Leedy vibraphone achieved a degree of popularity after it was used in the novelty recordings of "Aloha 'Oe" and "Gypsy Love Song" in 1924 by vaudeville performer Louis Frank Chiha.[8][9]

The popularity of Leedy's instrument led competitor J.C. Deagan, Inc., the inventor of the original steel marimba which Leedy's design was based on, to ask its chief tuner, Henry Schluter, to develop a similar instrument in 1927. However, instead of just copying the Leedy design, Schluter introduced several significant improvements: making the bars from aluminum instead of steel for a more "mellow" tone, adjustments to the dimensions and tuning of the bars to eliminate the dissonant harmonics in the Leedy design (further mellowing the tone), and the introduction of a foot-controlled damper bar allowing musicians to play it with more expression. Schluter's design became more popular than the Leedy design and has become the template for all instruments now called "vibraphone".[10]

However, when Deagan began marketing Schluter's instrument in 1928, they called it the "vibraharp".[11] Since Deagan trademarked the name, other manufacturers were forced to use the earlier name "vibraphone" for their instruments incorporating the newer design.

The use of the vibraphone in jazz was popularized by Lionel Hampton, a jazz drummer from California.[12] At one recording session with bandleader Louis Armstrong, Hampton was asked to play a vibraphone that had been left behind in the studio.[13] This resulted in the recording of the song "Memories of You" in 1930, a song often considered to be the first instance of an improvised vibraphone solo.[14][15]

The first classical composers to use the vibraphone were Alban Berg, who used it prominently in his opera Lulu in 1935,[16][17] and William Grant Still, who used it in his piece Kaintuck' in the same year.[18] While the vibraphone has not been used quite as extensively in the realm of classical music, it can often be heard in theatre or film music, such as in Bernstein's West Side Story.

The initial purpose of the vibraphone was to add to the large arsenal of percussion sounds used by vaudeville orchestras for novelty effects. This use was quickly overwhelmed in the 1930s by its development as a jazz instrument. As of 2020, it retains its use as a jazz instrument and is established as a major keyboard percussion instrument, often used for solos, in chamber ensembles, and in modern orchestral compositions.[3][19]

Manufacturers[]

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, each manufacturer attracted its own following in various specialties, but the Deagan vibraphones were the models preferred by many of the emerging class of specialist jazz players. Deagan struck endorsement deals with many of the leading players, including Lionel Hampton and Milt Jackson. The Deagan company went out of business in the 1980s and its trademark and patents were purchased by Yamaha.[20] Yamaha continues to make percussion instruments based on the Deagan designs.[21]

In 1948, the Musser Mallet Company was founded by Clair Omar Musser, who had been a designer at Deagan. The Musser company continues to manufacture vibraphones as part of the Ludwig Drum Company and is considered by many to be the industry standard.[22]

As of 2020, there are numerous manufacturers of the vibraphone that make vibraphones with ranges up to 4 octaves (C3–C7). The list includes Adams, Bergerault, DeMorrow, Majestic, Malletech, Marimba One, Musser, Premier, and Yamaha.

Range[]

The standard modern instrument has a range of three octaves, from the F below middle C (F3 to F6 in scientific pitch notation). Larger 3+1⁄2- or 4-octave models from the C below middle C are also becoming more common (C3 to F6 or C7). Unlike its cousin the glockenspiel, it is a non-transposing instrument, generally written at concert pitch. However, composers occasionally (for example, Olivier Messiaen) write parts to sound an octave higher.

In the 1930s several manufacturers made soprano vibraphones with a range C4 to C7, notably the Ludwig & Ludwig Model B110 and the Deagan Model 144. Deagan also made a portable model that had a 2+1⁄2-octave range and resonators made of cardboard (Model 30).[23]

Construction[]

The major components of a vibraphone are the bars, resonators, damper mechanism, motor, and the frame. Vibraphones are usually played with mallets.

Bars[]

Vibraphone bars are made from aluminum bar stock, cut into blanks of predetermined length. Holes are drilled through the width of the bars, so they can be suspended by a cord, typically parachute cord. To maximize the sustain of the bars, the holes are placed at approximately the nodal points of the bar (i.e. the points of minimum amplitude, around which the bar vibrates). For a uniform bar, the nodal points are located 22.4% from each end of the bar.[24]

Material is ground away from underside of the bars in an arch shape to lower the pitch. This allows the lower-pitched bars to be a manageable length. It is also the key to the "mellow" sound of the vibraphone (and marimba, which uses the same deep arch) compared with the brighter xylophone, which uses a shallower arch, and the glockenspiel, which has no arch at all. These rectangular bars have three primary modes of vibration.[24] The deep arch causes these modes to align and create a consonant arrangement of intervals: a fundamental pitch, a pitch two octaves above that, and a third pitch an octave and a major third above the second. For the F3 bar that usually forms the lowest note on a vibraphone, there would be F3 as the fundamental, F5 as the first overtone and A6 as the second overtone.[24] As a side effect, the arch causes the nodal points of the fundamental vibration to shift closer towards the ends of the bar.

After beveling or rounding the edges, fine-tuning adjustments are made. If a bar is flat, its overall pitch structure can be raised by removing material from the ends of the bar. Once this slightly sharp bar is created, the secondary and tertiary tones can be lowered by removing material from specific locations of the bar.[24] Vibraphones are tuned to a standard of A = 442 Hz or A = 440 Hz, depending on the manufacturer or in some cases the customer's preference.

Like marimbas, professional vibraphones have bars of graduated width. Lower bars are made from wider stock, and higher notes from narrower stock, to help balance volume and tone across the range of the instrument. The bars are anodized, typically in silver or gold color, after fine-tuning and may have a smooth or brushed (matte) finish. These are cosmetic features with a negligible effect on the sound.

Resonators[]

Resonators are thin-walled tubes, typically made of aluminum, but any suitably strong material can be used. They are open at one end and closed at the other. Each bar is paired with a resonator whose diameter is slightly wider than the width of the bar and whose length to the closure is one-quarter of the wavelength of the fundamental frequency of the bar.[24] When the bar and resonator are properly in tune with each other, the vibrating air beneath the bar travels down the resonator and is reflected from the closure at the bottom, then returns to the top and is reflected back by the bar, over and over, creating a much stronger standing wave and increasing the amplitude of the fundamental frequency. The resonators, besides raising the upper end of the vibraphone's dynamic range, also affect the overall tone of the vibraphone, since they amplify the fundamental, but not the upper partials.

Oftentimes, vibraphones, and other mallet instruments, will include non-functional, decorative resonator tubes with no corresponding bar above to make the instrument look more full.[25]

There is a trade-off between the amplifying effect of the resonators and the length of sustain of a ringing bar. The energy in a ringing bar comes from the initial mallet strike, and that energy can either be used to make the bar ring louder initially, or not as loudly but for a longer period of time. This is not an issue with marimbas and xylophones, where the natural sustain time of the wooden bars is short, but vibraphone bars can ring for many seconds after being struck, and this effect is highly desirable in many circumstances. Therefore, the resonators in a vibraphone are usually tuned slightly off-pitch to create a balance between loudness and sustain.[26]

A unique feature of vibraphone resonators is a shaft of rotating discs, commonly called fans, across the top. When the fans are open, the resonators have full function. When the fans are closed, the resonators are partially occluded, reducing the resonance of the fundamental pitch. A drive belt connects the shafts to an electric motor beneath the playing surface and rotates the fans. This rotation of the fans creates a vibrato effect along with some volume changes creating a tremolo effect.[27][28]

In 1970, Deagan introduced a model "Electravibe", which dispensed with resonator tubes entirely and took a signal directly from the bars, adding a tremolo in a preamplifier. This sought to improve the portability of the instrument and solve the problem inherent in all tuned mallet instruments; miking the bars evenly.

Damper mechanism[]

For the first few years of production, the original Leedy Vibraphone did not include a mechanism for damping, or stopping, the sustaining tones. In 1927, the J.C. Deagan company introduced a pedal mechanism that has not changed substantially since.[27] A rigid bar beneath the center of the instrument is pressed upward by an adjustable spring and engages a long felt pad against the sharps and the naturals. A foot pedal lowers the bar and allows notes to ring freely; releasing the pedal engages the damper and stops any vibrating notes. One common flaw of this damping mechanism is that the bar is often supported at one point in the middle, causing it to damp the instrument unevenly in the upper and lower registers. To combat this, some manufacturers have made silicone- or liquid-filled damper pads whose fluid shape can conform evenly around the bars.[29][30]

Motors[]

Vibraphones usually have an electric motor and pulley assembly mounted on one side or the other to drive the disks in the resonators. Often, mainly in classical music or in non-jazz ensembles like a percussion ensemble or front ensemble, the vibraphone is played with the motor off and the disks not moving. In those cases having the motor off is the norm and is not used unless specifically called for.[31][32][33][34]

The early vibraphones used motors that were intended to power record-player turntables[8] and had limited or no speed-adjustment capabilities. Whatever speed adjustments were possible were made by moving the drive belt among a small number of pulleys (usually three) of varying diameters. Later, variable-speed AC motors became available at reasonable prices. These motors allow the adjustment of the rotating speed by a potentiometer mounted on a control panel near the motor. They typically support rotation rates in the range 1–12 Hz. These motors remained the preferred solution until the 1990s and are still in use by some manufacturers.

During the 1990s, some manufacturers began using computer-controlled stepping motors. These motors are capable of slower rotating speeds, approaching 0 Hz. The computer control also allows operations that are not possible with an analog motor, such as the ability to synchronize the rotation of the two resonator sets and stop the rotation at a desired state (e.g. all open, all closed, all half-open, etc.).[35]

Frame[]

The vibraphone frame offers a number of challenges to designers. It must be sturdy enough to endure the torsional forces created by the damper/spring/pedal assembly and the stresses of repeated transport and playing, while still being light enough for easy transport. Considering the weight of the bars alone, this does not leave much margin for the frame. The bars must also be securely attached to the frame, but not rigidly. Each bar must have some independent flex for it to ring.

The motor is attached to the frame at one end. The hinges for the damper bar are attached at each end, and the spring assembly and the pedal are usually aligned in the middle. Two banks of resonator tubes are laid into grooves in the frame so that they straddle the damper bar. The resonators are not firmly fastened to the frame. The ends of the shafts that gang the disks are connected to the drive of the motor through a drive belt similar to an O-ring.

A bed for the bars is made by laying four wooden rails onto pins on the end blocks. Like the resonators, these rails do not firmly attach to the frame. Each rail has a series of pins with rubber spacers that support the bars. The bars are arranged into two groups, and a soft cord passes through the nodal holes in the bars of each group. These bars lay between the support pins, with the cord hooking the pins. On the outside rails, the pins have U-shaped hooks, and the cord rests in the bend. the inside pins have a hook that grasps the cord and holds the bars in place against the force of the damper pad. The two ends of the cord attach with a spring at one end to provide tension and flex.[36]

Mallets[]

Vibraphone mallets usually consist of a rubber ball core wrapped in yarn or cord and attached to a narrow dowel, most commonly made of rattan or birch and sometimes of fiberglass or nylon. Mallets suitable for the vibraphone are also generally suitable for the marimba.

The mallets can have a great effect on the tonal characteristics of the sound produced, ranging from a bright metallic clang to a mellow ring with no obvious initial attack. Consequently, a wide array of mallets is available, offering variations in hardness, head size, weight, shaft length, and flexibility.

Classical players must carry a wide range of mallet types to accommodate the changing demands of composers who are looking for particular sounds. Jazz players, on the other hand, often make use of multi-purpose mallets to allow for improvisation.[37]

Technique[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

The world of vibraphone players can be roughly divided into those who play with two mallets and those who play with four. In reality the division is not strict: many players switch between two, three and four mallets depending on the demands of their current musical situations.

Furthermore, concentrating on the number of mallets a player holds means missing the far more significant differences between the two-mallet and four-mallet playing styles.

Two-mallet style[]

The two-mallet approach to vibes is traditionally linear, playing like a horn rather than comping like a guitar or piano. Two-mallet players usually concentrate on playing a single melodic line and rely on other musicians to provide accompaniment. Double stops (two notes played simultaneously) are sometimes used, but mostly as a reinforcement of the main melodic line, similar to the usual use of double stops in solo violin music. In jazz groups, two-mallet vibraphonists are usually considered part of the "front line" with the horn players, contributing solos of their own but contributing very little in the way of accompaniment to other soloists.

Two-mallet players use several different grips, with the most common being a palms-down grip, which is basically the same as the matched grip used by drummers. The mallets are held between the thumb and index finger of each hand, with the remaining three fingers of each hand pressing the shafts into the down-facing palms. Strokes use a combination of wrist movement and fingertip control of the shaft.

Another popular grip is similar to French grip, a grip used on timpani. The mallets are again held between the thumb and index fingers and controlled with the remaining three fingers, but the palms are held vertically, facing inward towards each other. Most of the stroke action comes from the finger-tip control of the shafts.

Passages are usually played hand-to-hand with double-sticking (playing two notes in a row with the same hand) used when convenient in minimizing crossing the hands.

The player must pay close attention to the damper pedal to play cleanly and avoid multiple notes ringing unintentionally at the same time. Because the notes ring for a significant fraction of a second when struck with the damper pad up, and ringing bars do not stop ringing immediately when contacted by the pad, players use a technique called after pedaling.[38] In this technique, the player presses the damper pedal slightly after striking the bar—shortly enough so the recently struck note continues to ring, but long enough so that the previous note stops ringing.

In another damper technique—half pedaling—the player depresses the pedal just enough to remove the spring pressure from the bars, but not enough to make the pad lose contact with the bars. This lets the bars ring slightly longer than with the pad fully up and can make a medium-fast passage sound more legato without pedaling every note.

Four-mallet style[]

The four-mallet vibraphone style is multi-linear, like a piano. "Thinking like a pianist, arranger, and orchestrator, the vibist approaches the instrument like a piano and focuses on a multi-linear way of playing."[39] In jazz groups, four-mallet vibraphonists are often considered part of the rhythm section, typically substituting for piano or guitar and providing accompaniment for other soloists in addition to soloing themselves. Furthermore, the four-mallet style has led to a significant body of unaccompanied solo vibes playing. One notable example is Gary Burton’s performance of "Chega de Saudade (No More Blues)" from his Grammy-winning 1971 album "Alone at Last".[40]

Although some early vibes players made use of four mallets, notably Red Norvo, Adrian Rollini, and sometimes Lionel Hampton, the fully pianistic four-mallet approach to jazz on the vibraphone is almost entirely the creation of Burton. Many of the key techniques of the four-mallet style, such as multi-linear playing and the advanced damping techniques described below, are easily applied to playing with two mallets and some modern two-mallet players have adapted these devices to their playing, somewhat blurring the distinctions between modern two- and four-mallet players.

The most popular four-mallet grip for vibraphone is the Burton grip, named for Gary Burton. One mallet is held between the thumb and index finger and the other is held between the index and middle fingers. The shafts cross in the middle of the palm and extend past the heel of the hand. For wide intervals, the thumb often moves in between the two mallets, and the inside mallet is held in the crook of the fingers.

Also popular is the Stevens grip, named for marimbist Leigh Howard Stevens. Many other grips are in use, some variations on the Burton or Stevens, others idiosyncratic creations of individual vibes players. One common variation of the Burton grip places the outside mallet between the middle and ring fingers instead of between the index and middle.[41]

Four-mallet vibists usually play scalar linear passages much the same as two-mallet players, using one mallet from each hand (outside right and inside left for Burton grip), except that four-mallet players tend to make more use of double strokes, not only to avoid crossing hands, but also to minimize motion between the two bar rows. For example, an ascending E flat major scale could be played L-R-R-L-L-R-R-L, keeping the left hand on the "black" bars and the right hand on the "white". For linear passages with leaps, all four mallets are often used sequentially.[39]

Pedaling techniques are at least as important for the four-mallet vibist as for two-mallet players, but the all-or-nothing damping system of the pedal/pad presents many obstacles to multi-linear playing, since each line normally has its own damping requirements independent of the other lines. To overcome this, four-mallet players use a set of damping techniques referred to as "mallet damping", in addition to the pedaling techniques used by two-mallet players. There are many benefits of being proficient in this technique as a vibraphonist. As it allows a player to hold out one chord and add or subtract any individual pitch desired, a vibist can transition between chords much more smoothly than a pianist who cannot stop a string from vibrating without reaching inside the instrument when the pedal is down. Most modern vibraphonists are highly skilled in this technique. The mallet damping techniques "are to the vibist as garlic and fresh basil are to the Northern Italian chef" and contribute significantly to expressive four-mallet playing.[42]

Mallet damping includes "dead strokes", where a player strikes a bar and then, instead of drawing the mallet back, directly presses the head of the mallet onto the bar, causing the ringing to stop immediately. This produces a fairly distinctive "choked" sound, and dead strokes are often used just for that particular sound in addition to the damping aspects.[43]

In hand-to-hand damping, the vibist plays a note with one mallet, while simultaneously pressing another mallet onto a previously ringing bar. Usually the damping mallet and the striking mallet are held in different hands, but advanced players can, in some circumstances, use two mallets from the same hand.[44] This is the most powerful of the mallet damping techniques, as it can be used to damp any note on the instrument while simultaneously striking any other note.[42]

Slide damping can be used to damp a note that is physically adjacent to the new note being struck. The player strikes the new note and then controls the rebound of the mallet so that it slides over and onto the note to be damped.[42] Sometimes slide damping can make the new note sound "bent" or as if there is a glissando from the damped note to the ringing one, as the two notes normally ring together for some short period of time.

Hand damping (also known as finger damping) can be used to damp a white note while striking a nearby black note.[42] As the player strikes a black note with a mallet, they simultaneously press the heel of their hand or the side of their pinky finger onto the ringing white bar, using the same hand to strike the black note and damp the white note. Using both hands, it's possible to damp and strike two notes at once.

Specialty techniques[]

Five or six mallets[]

To achieve denser sound and richer chord voicings, some vibraphonists have experimented with three mallets per hand, either in both hands for a total of six mallets or in just the left hand for a total of five.

Bowing[]

Like many other metallophones, percussionists can use an orchestral bow on the vibraphone to achieve sustained tones that neither decay, nor have a percussive attack.[45][46]

Classical works with the vibraphone[]

Although the vibraphone has been predominantly used for jazz music, many classical pieces have been composed using the instrument, either as featured soloist or with a prominent part. Notable works include:

- Ferde Grofe: Grand Canyon Suite (1931)

- Alban Berg: Lulu (1935)

- Roy Harris: Symphony No. 3 (1939)

- Morton Gould: Harvest, for vibraphone, harp, and strings (1945)

- Darius Milhaud: Concerto for marimba, vibraphone, and orchestra, Op. 278 (1947)

- Benjamin Britten: Spring Symphony (1948–1949)

- Ralph Vaughan Williams: Sinfonia antartica (Symphony No. 7) (1952)

- Alan Hovhaness: The Flowering Peach, incidental music to the play by Clifford Odets, for clarinet, alto saxophone, timpani, tam-tam, vibraphone, glockenspiel, harp, and celesta, Op. 125 (1954)

- Ralph Vaughan Williams: Symphony No. 8 (1955)

- Pierre Boulez: Le marteau sans maître for contralto and six instrumentalists, with prominent part for vibraphone (1955)

- Benjamin Britten: The Prince of the Pagodas (1957)

- Siegfried Fink: Concerto for vibraphone and orchestra (1958–59)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: Refrain, for piano, vibraphone, and celesta (1959)

- William Walton: Symphony No. 2 (1960)

- Leonard Bernstein: Symphonic Dances from West Side Story (1961)

- Jean Barraqué: Concerto for vibraphone, clarinet, and six instrumental groups (1962–68)

- René Leibowitz: Trois Caprices for vibraphone op.70 (1966)

- Igor Stravinsky: Requiem Canticles (1966)

- Mieczysław Weinberg: The Passenger (1968)

- Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 14 (1969)

- Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 15 (1971)

- Alan Hovhaness: Spirit Cat, suite for soprano, vibraphone, and marimba, Op. 253 (1971)

- Benjamin Britten: Death in Venice (1973)

- Stuart Saunders Smith: Links series, 11 works (1975–1994)

- Tomáš Svoboda: Morning Prayer, for four percussionists, Op. 101 (1981)

- Tomáš Svoboda: Baroque Trio, for vibraphone, electric guitar, and piano, Op. 109 (1982)

- Steve Reich: Sextet, for four percussionists and two keyboardists (1984–1985)

- Franco Donatoni: Omar (1985)

- Pierre Boulez: "...explosante-fixe...", version for vibraphone and electronics (1986)

- Morton Feldman: For Stefan Wolpe for chorus and two vibraphones (1986)

- Philippe Manoury: Solo de vibraphone (1986)

- Lior Navok: V5—for vibraphone and string quartet (1994)

- Emmanuel Séjourné: Concerto for vibraphone and orchestra; Concerto for vibraphone and piano (1999)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: Strahlen for vibraphone (optionally with glockenspiel) and ten-channel electronic music (2002)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: Vibra-Elufa for vibraphone (2003)

- Gil Shohat: Tyre and Jerusalem (2003)

- William P. Perry: Jamestown Concerto (2008)

- Gil Shohat: The Child Dreams (2010),

- Luigi Morleo: Diritti: NO LIMIT Concerto for Vibraphone and String Orchestra (2013)

- Tommy Vig: Concerto for vibraharp and orchestra (2013)

- Fabian Müller: Concerto for Vibraphone and Orchestra (2014)

- Pascal Schumacher: Windfall Concerto for vibraphone and orchestra (2016)

Use in film scores[]

Bernard Herrmann used the vibraphone extensively in many of his film and television scores, most notably in his scores for Fahrenheit 451 and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Vibist definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ "The Deagan Resource". www.deaganresource.com. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blades, James; Holland, James. "Vibraphone". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed August 17, 2015.

- ^ Siwe, Thomas (1995). Percussion Solo Literature. Media Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780963589118.

- ^ "Leedy Vibraphone". Rhythm! Discovery Center. Archived from the original on 2020-09-23. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ "History - Vienna Symphonic Library". www.vsl.co.at. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ Strain, James Allen. A dictionary for the modern percussionist and drummer. Lanham, Maryland. ISBN 978-0-8108-8692-6. OCLC 972798459.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Vibraphone: A Summary of Historical Observations with a Catalog of Selected Solo and Small-Ensemble Literature; by Harold Howland; Percussionist, volume 13, no. 2, Summer 1977.

- ^ Stallard, Carolyn (July 2015). "The Vibraphone: Past, Present, and Future".

- ^ J.C. Deagan Inc., (1977), The Story of Mallet Instruments (Film)

- ^ "Deagan Vibraharps". Malletshop.

- ^ Harrison, David (2012-10-19). "Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. Volume VIII Genres: North America Edited by David Horn. Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. Volume VIII Genres: North America. New York, NY and London: Continuum 2012. xviii+561 pp., 2012362; ISBN: 978 1 4411 6078 2 £150 $250". Reference Reviews. 26 (8): 50–51. doi:10.1108/09504121211278430. ISSN 0950-4125.

- ^ "Lionel Hampton | American musician". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ "Feeling The Vibes: The Short History of a Long Instrument". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ "History - Vienna Symphonic Library". www.vsl.co.at. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ "Vibraphone | musical instrument". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Blades, James (1992). Percussion instruments and their history (Rev. ed.). Westport, Conn.: Bold Strummer. ISBN 0-933224-71-0. OCLC 28230162.

- ^ "Kaintuck'". www.musicshopeurope.com. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ Keller, Renee (June 2013). "Compositional and Orchestrational Trends in the Orchestral Percussion Section Between the Years of 1960-2009" (PDF).

- ^ Strain, James A. "John Calhoun Deagan". Hall of Fame. Indianapolis, IN: Percussive Arts Society. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- ^ "Percussion – Musical Instruments". Yamaha. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- ^ "Musser". Our Brands. Conn-Selmer, Inc. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- ^ "The Deagan Resource".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Acoustics of Bar Percussion Instruments; James L. Moore, Ph.D.; Permus Publications.

- ^ "The Structure of the Marimba:Inside and outside the resonator pipes - Musical Instrument Guide - Yamaha Corporation". www.yamaha.com. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ Bars, Resonators. http://www.vibesworkshop.com/story/bars-resonators-their-behaviour-and-how-act-it/nico/120608,[permanent dead link] requires membership to access.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Leedy Vibraphone". Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ "Anatomy of a Vibraphone". hub.yamaha.com. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ "Vibraphone Pedaling". www.malletjazz.com. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ M-58 Piper Vibe User Manual Ludwig

- ^ Reich, Steve, 1936- (2002). Writings on music, 1965-2000. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535478-2. OCLC 59280675.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Nelson, R. 1969. Rocky Point Holiday. Boosey and Hawkes

- ^ Moyer, I. 2020. Front Ensemble Friday: Iain Moyer – A Marimbists & Arrangers Guide to Vibraphone. Marching Arts Education.

- ^ Reich, S. 1984. Sextet. Boosey and Hawkes

- ^ "Our Vibraphones | Marimba One". www.marimbaone.com. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ Sims, Brandon (2010). "Vibraphone Patent" (PDF). Conn-Selmer.

- ^ Vic Firth Artist: Gary Burton (with video). Archived 2007-07-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ed Saindon, Technical Considerations (video). Archived 2007-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ed Saindon, Sound Development and Four-Mallet Usage for Vibes. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Gary Burton Biography". Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved July 12, 2007.

- ^ Tony Miceli, The Miceli Stoned Grip (video).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d The Vibes Real Book, Arthur Lipner, MalletWorks Music, 1996.

- ^ United States Army. "Percussion Techniques" (PDF).

- ^ Ed Saindon, Do You Know What It Means (to Miss New Orleans) (video). Archived 2007-07-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Extended Techniques for Vibraphone". www.malletjazz.com. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ Smith, Joshua. (2008). Extended Performance Techniques and Compositional Style in the Solo Concert Vibraphone Music of Christopher Deane. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc9030/m2/1/high_res_d/dissertation.pdf (pg. 14)

Further reading[]

- Introduction to Jazz Vibes; by Gary Burton; Creative Music; 1965.

- Contemporary Mallet Method – An Approach to the Vibraphone and Marimba; by Jerry Tachoir: ; 1980

- The Mallet Percussions and How to Use Them: by Wallace Barnett; J.C. Deagan Company: 1975

- The Story of Mallet Instruments: 16mm and DVD: by Barry J. Carroll J.C. Deagan Company: 1975

- Udow, Michael (2019-07-10), Percussion Pedagogy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-090296-4

- Cook, Gary D. (2018-01-01), Teaching Percussion, Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-1-337-67222-1

External links[]

Media related to Vibraphones at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vibraphones at Wikimedia Commons- Reich Sextet Performs "Camerata Pacifica" on YouTube

- Mallet Damping – demonstration by Gary Burton

- C instruments

- Jazz instruments

- Keyboard percussion

- Metal percussion instruments

- Percussion instruments invented since 1800

- Pitched percussion

- Plaque percussion idiophones

- American inventions

- Music performance