Victor Schœlcher

Victor Schœlcher | |

|---|---|

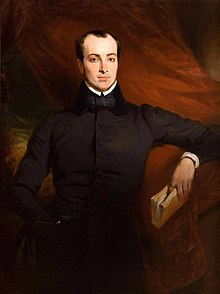

Portrait by Henri Decaisne, 1832 | |

| Deputy of the National Assembly[1] | |

| In office 9 August 1848 – 26 May 1849 | |

| Constituency | Martinique |

| In office 24 June 1849 – 17 October 1849 | |

| Constituency | Guadeloupe |

| In office 13 January 1850 – 2 December 1851 | |

| Constituency | Guadeloupe |

| In office 12 March 1871 – 7 March 1876 | |

| Constituency | Martinique |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 July 1804 Paris, France |

| Died | 25 December 1893 (aged 89) Houilles, France |

| Resting place | Panthéon |

| Nationality | French |

| Political party | The Mountain (Second Republic) Republican Union (Third Republic) |

Victor Schœlcher (French: [viktɔʁ ʃœlʃɛʁ]; 22 July 1804 – 25 December 1893) was a French abolitionist writer, politician and journalist, best known for his work towards and leading role in the abolition of slavery in France in 1848, during the French Second Republic.

Early life[]

Schœlcher was born in Paris on 22 July 1804. His father, Marc Schœlcher (1766–1832), from Fessenheim in Alsace, was the owner of a porcelain factory.[2] His mother, Victoire Jacob (1767–1839), from Meaux in Seine-et-Marne, was a laundry maid in Paris at the time of their marriage. He was baptized in Saint-Laurent Church on 9 September 1804.

He enrolled in the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in 1818, but left one year later and began working at the family's porcelain factory in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis. In his teenage years Schœlcher became an opposer of the Bourbon monarchy while frequenting the literary and political salons of Paris.[2] In 1820, at the age of 16, he joined Freemasonry, being initiated into the Parisian lodge "Les Amis de la Vérité" (Grand Orient de France),[3], which was at the time very strongly politicized for not saying openly revolutionary. He later moved to another Parisian lodge, “La Clémente Amitié”.[4]

Abolitionism[]

In 1828, Schœlcher was sent by his father in an eighteen months-long trip in America, as a business representative of the family's enterprise. While in the continent he visited Mexico, Cuba,[2] and the southern United States.[5] On this trip he learned much about slavery and began his career as an abolitionist writer, and returning to France in 1830 he published his first writing in the Revue de Paris, an article titled Des noirs ("Of the blacks"), in which he proposed a gradual abolition of slavery.[6] Schœlcher inherited the family's business on his father's death in 1832, but sold it on order to dedicate himself to his abolitionist work. In the following years he traveled through Europe, and in 1840[6] went to the West Indies to further study slavery and the results of its abolition in the English colonies. Next he went to Egypt, Greece and Turkey, where he studied Muslim slavery, and finally to West Africa, traveling through Senegal and Gambia between September 1847 and January 1848.[2]

With the first-hand accounts and the knowledge on slavery acquired in his travels, Schœlcher became an advocate for the immediate emancipation of slaves, no longer supporting a gradual process. These ideas were published in his work Des colonies françaises: Abolition immédiate de l'esclavage ("Of the French colonies: Immediate abolition of slavery") in 1842,[5] following his return from the West Indies.[2] He was a member of the Société française pour l'abolition de l'esclavage founded in 1834, modeled after contemporary British abolitionist societies.[6] After the early 1830s he was also a republican activist in France, and was one of the founders of the progressive newspaper La Réforme in 1843,[2] to which he was a regular contributor.[5]

Schœlcher elaborated on social, economic, and political reforms he believed would be necessary to the Caribbean colonies after the abolition of slavery.[5] He thought that the production of sugar could continue, though it should be rationalized with the construction of large central factories, and defended the reduction of concentration of land. Schœlcher was the first European abolitionist to visit Haiti after its independence, and had a large influence on the abolitionist movements in all of the French West Indies.[5] He was actively against the debt collected from the Haitians as French slave owners sought reparations for their property lost in the Haitian Revolution.[7]

In February 1848, a Revolution in France overthrew the July Monarchy. Schœlcher arrived from Senegal a few days later, on 3 March, and quickly went to meet with François Arago, Minister of the Navy and colonies of the provisional government of the new French Republic, who appointed him under-secretary of State for the colonies, on 4 March, as well as president of a new commission charged with drafting the immediate abolition of slavery,[2] with Louis Percin and Henri-Alexandre Wallon assigned as its secretaries.[8]

Schœlcher had convinced Arago not to wait until the calling of the constituent National Assembly, which would be deeply occupied with the organization of the republican institutions, to establish the abolitionist commission, arguing that any postponing of the emancipation could lead to revolt and bloodshed in the colonies.[8] In his capacity as under-secretary of state and president of the commission, Schœlcher prepared and wrote the decree that was issued on 27 April 1848, in which the French government announced the immediate abolition of slavery in all of its colonies and granted citizenship to the emancipated slaves.[5]

Later career[]

Schœlcher's ultimate success in ending slavery gave birth to a new republican political movement in the Caribbean colonies.[5] He was elected deputy to the Legislative Assembly in 1848 for Martinique. The next year he ran for reelection but was defeated by Cyrille Bissette, a former "free man of colour" and abolitionist, but won in Guadeloupe and was again elected for that department in 1850.[1] He introduced a bill for the abolition of the death penalty, which was to be discussed on the day on which President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte seized power with a coup d'état, on 2 December 1851 and dissolved the National Assembly. The next day, Schœlcher was one of the few deputies present at the barricades in Paris to resist the coup, alongside Jean-Baptiste Baudin.[9]

Schœlcher was then exiled by the new regime,[6][9] staying shortly in Belgium before going to London, where he settled in 1852. In the next years he became an specialist in the work of Georg Friedrich Handel, writing a biography of him in 1857.[2] At the same time he published multiple writings criticizing Napoleon III, formerly president of France and now monarch of the French Empire, in works such as Dangers to England of the alliance with the men of the Coup d'Etat, which Schœlcher wrote in English and published in 1854. During this time he became a friend of fellow republican exile Victor Hugo.[5]

Refusing to take advantage of the amnesty of 1859,[5] Schœlcher returned to France only in late August 1870, after the declaration of war with Prussia. He was appointed staff colonel of the National Guard on 4 September, the day of the deposition of Napoleon III and the proclamation of the Third Republic.[9] Organizing a legion of artillery, he took part in the defence of Paris. In 1871 he was again elected by Martinique for the National Assembly in Bordeaux, where he voted against the peace treaty. On the outbreak of the Paris Commune, Schœlcher tried in vain to establish an understanding between the insurgents and the government, being arrested by the communards but set free three days later. Afterwards he continued serving in the National Assembly as a member of the Republican Union,[9] and was elected senator for life in December 1875.[6] In July 1876 he renewed his proposal for the abolition of capital punishment.[9]

In 1875 Schœlcher became a member of the Societé pour l'amélioration du sort de la femme ("Society for the improvement of women's condition"), and co-founded with Gaston Gerville-Réache, in 1882, the newspaper Le Moniteur des Colonies.[2] He published his last work in 1889, a Vie de Tousaint Louverture ("Life of Toussaint Louverture").[5] After fighting for the abolition of slavery in French colonies and elsewhere for a large portion of the 19th century, Schœlcher died on 25 December 1893 in his house in Houilles, near Paris, at age 89.[2]

Having never married or left issue, in his will Schœlcher distributed his money and donated his collection to Guadeloupe, which is now housed in the Schœlcher Musem (Musée Schœlcher) in Pointe-à-Pitre. First buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, his remains were transferred on 20 May 1949 to the Panthéon on the initiative of Senator Gaston Monnerville from Guiana. Victor Schœlcher had wanted to be buried with his father Marc, who was therefore also interred in the Panthéon. The ashes of Félix Éboué, the first black person to be buried in the Panthéon, were also transferred at the same time.[6] In 1981, the newly elected President Francois Mitterrand placed a rose at his tomb in the Panthéon as part of his inauguration ceremony.[10]

Legacy[]

This section is in list format, but may read better as prose. (August 2021) |

- In homage to his fight against slavery, the commune of Case-Navire (Martinique) took the name of Schœlcher in 1888.

- The commune of Fessenheim turned his family's house into the Victor Schœlcher museum.

- The Place Victor Schœlcher in Aix-en-Provence is named for him.[11]

- A street created at the south-eastern corner of the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris was named Rue Schœlcher in 1894 and Rue Victor Schœlcher in 2000.

- Two ships of the French Navy have been named Victor Schœlcher - an auxiliary cruiser during World War II, and a Commandant Rivière-class frigate in service 1962-1988.

- On 20 May 2020 two statues of Schœlcher were destroyed in Martinique as part of the ongoing consequences of the Black Lives Matter movement that originated in the United States.[12] French President Emmanuel Macron criticized the acts. Another statue was destroyed in March 2021; their destruction was supported by activists from the separatist , and represents part of wider protests against "colonial memory".[13]

- He was honored on a commemorative note of five thousand francs by the department of Réunion first issued in 1946.[6]

Works[]

- De l'esclavage des noirs et de la législation coloniale (On slavery of blacks and colonial legislation) (Paris, 1833)

- Abolition de l'esclavage (Abolition of slavery) (1840)

- Les colonies françaises de l'Amérique (French colonies of America) (1842)

- Les colonies étrangères dans l'Amérique et Hayti (Foreign colonies in America and Haiti) (2 vols., 1843)

- Histoire de l'esclavage pendant les deux dernières années (History of slavery during the last two years) (2 vols., 1847)

- La verité aux ouvriers et cultivateurs de la Martinique (The truth to the workers and farmers of Martinique) (1850)

- Protestation des citoyens français negres et mulatres contre des accusations calomnieuses (Protests of black and mulatto French citizens against slanderous accusations) (1851)

- Le procès de la colonie de Marie-Galante (The trial of the Marie-Galante colony) (1851)

- Histoire des crimes du 2 décembre (History of the crimes of the 2 December) (1852)

- Le gouvernement du 2 décembre (The government of the 2 December) (1853)

- Dangers to England of the alliance with the men of the Coup d'Etat (1854)

- Vie de Händel (Life of Handel) (1857)

- La grande conspiration du pillage et du meurtre à la Martinique (The great conspiracy of theft and murder in the Martinique) (1875)

- Vie de Tousaint Louverture (1889)

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Victor Schoelcher". Assemblée nationale (in French). Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Victor Schoelcher (1804-1893)". Sénat (in French). Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Histoire de la franc-maçonnerie au XIXe siècle, tome 1, André Combes (édition du Rocher, Paris, 1998, page 136)

- ^ Dictionnaire Universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie - Jode and Cara (Larousse - 2011)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Schmidt, Nelly. "Victor Schoelcher". Ohio University. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Manière, Fabienne. "Victor Schoelcher (1804 - 1893) - Une vie vouée à l'abolition de l'esclavage". Herodote (in French). Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Jublin, Matthieu, ed. (12 May 2015). "French President's Debt Comment in Haiti Reopens Old Wounds About Slave Trade". Vice News. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jennings, Lawrence C. (2000). French Anti-Slavery: The Movement for the Abolition of Slavery in France, 1802-1848. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0521772494.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Robert, Adolphe; Cougny, Gaston (1891). Dictionnaire des parlementaires français (in French). 5. p. 288.

- ^ "L'émoi de mai". Journal de l'île de La Réunion. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Aix Google Map

- ^ Deux statues de Victor Schoelcher détruites le 22 mai, jour de la commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage en Martinique, la1ere.francetvinfo.fr, 22 May 2020

- ^ "'Proud to be colonised?': statue of French politician torn down in Martinique". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- Jan Rogozinski – A Brief History Of The Caribbean (New York: Plume, 2000)

- James Chastain – Victor Schœlcher. Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions 2004 James Chastain [1].

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

External links[]

- List of works in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France database

Bibliography[]

- Schœlcher, Victor. De la pétition des ouvriers pour l'abolition immédiate de l'esclavage, Paris, Pagnerre, 1844. Manioc

- Schœlcher, Victor. Restauration de la traite des noirs à Natal, Paris, Imprimerie E. Brière, 1877. Manioc

- Schœlcher, Victor. Evénements des 18 et 19 juillet 1881 à Saint-Pierre (Martinique), Paris, Dentu, 1882. Manioc

- Schœlcher, Victor. Conférence sur Toussaint Louverture, général en chef de l'armée de Saint-Domingue, [s.l.], Editions Panorama, 1966. Manioc

- Monnerot, Jules. Schœlcher, [s.l.], Imprimerie Marchand, 1936. Manioc

- Basquel, Victor. Un grand ancêtre : Victor Schœlcher (1804-1893), Rodez, Imprimerie P. Carrère, 1936. Manioc

- Magallon Graineau, Louis-Alphonse Eugène. L'exemple de Victor Schœlcher, Fort-de-France, Imprimerie officielle, 1944. Manioc

- 1804 births

- 1893 deaths

- Writers from Paris

- 19th-century French journalists

- 19th-century French non-fiction writers

- French biographers

- Politicians from Paris

- The Mountain (1849) politicians

- Republican Union (France) politicians

- Government ministers of France

- Members of the 1848 Constituent Assembly

- Members of the National Legislative Assembly of the French Second Republic

- Members of the National Assembly (1871)

- French Life Senators

- French abolitionists

- French male writers

- French Freemasons

- French atheists

- Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Burials at the Panthéon, Paris

- French anti–death penalty activists

- Male feminists

- French feminists