Virginia-class submarine

USS Virginia underway in July 2004

| |

Virginia-class SSN profile

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders | |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Seawolf class |

| Cost | $2.8 billion per unit;[1] $3.4 billion per unit w/ VPM[1] |

| Built | 2000–present |

| In commission | 2004–present |

| Planned | 66[1] |

| On order | 8 |

| Building | 11 |

| Completed | 19 |

| Cancelled | 0 |

| Active | 19 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Nuclear attack submarine |

| Displacement |

|

| Length |

|

| Beam | 34 ft (10 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 × S9G nuclear reactor[3] 280,000 shp (210 MW)

2 × steam turbines 40,000 shp (30 MW) 1 × single shaft pump-jet propulsor[3] 1 × secondary propulsion motor[3] |

| Speed | 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) or over[6] |

| Range | Unlimited |

| Endurance | Only limited by food and maintenance requirements. |

| Test depth | Over 800 ft (240 m) |

| Complement | 135 (15 officers; 120 enlisted) |

| Armament |

|

The Virginia class, also known as the SSN-774 class, is a class of nuclear-powered cruise missile fast-attack submarines, in service in the United States Navy. Designed by General Dynamics's Electric Boat (EB) and Huntington Ingalls Industries, the Virginia-class is the United States Navy's latest submarine model, which incorporates the latest in stealth, intelligence gathering, and weapons systems technology.[7][8]

Virginia-class submarines are designed for a broad spectrum of open-ocean and littoral missions, including anti-submarine warfare and intelligence gathering operations. They are scheduled to replace older Los Angeles-class submarines, many of which have already been decommissioned. Virginia-class submarines will be acquired through 2043, and are expected to remain in service until at least 2060, with later submarines expected to remain into the 2070s.[9][10]

History[]

The class was developed under the codename Centurion, later renamed New SSN (NSSN).[11][12] The "Centurion Study" was initiated in February 1991.[13] The Virginia-class submarine was the first US Navy warship with its development coordinated using such 3D visualization technology as CATIA, which comprises computer-aided engineering (CAE), design (CAD), manufacturing (CAM), and product lifecycle management (PLM). Design problems for Electric Boat – and maintenance problems for the Navy – ensued nonetheless.[14][15][16]

By 2007 approximately 35 million labor hours had been spent to design the Virginia.[17] Constructing a single Virginia-class submarine has required around nine million labor hours,[16][18][19] and over 4,000 suppliers.[20] Each submarine is projected to make 14–15 deployments during its 33-year service life.[21]

The Virginia class was intended in part as a less expensive alternative to the Seawolf-class submarine ($1.8 billion vs $2.8 billion), whose production run was canceled after just three boats had been completed. To reduce costs, the Virginia-class submarines use many "commercial off-the-shelf" (COTS) components, especially in their computers and data networks. Improvements in shipbuilding technology have trimmed production costs below the $1.8 billion projected fiscal year 2009 dollars.[22]

In hearings before both House of Representatives and Senate committees, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) and expert witnesses testified that the annual procurement rate of only one Virginia class boat – rising to two in 2012 – would result in excessive unit production costs, yet an insufficient complement of attack submarines.[23] In a 10 March 2005 statement to the House Armed Services Committee, Ronald O'Rourke of the CRS testified that, assuming that the production rate remains as planned, "production economies of scale for submarines would continue to remain limited or poor."[24]

In 2001, Newport News Shipbuilding and the General Dynamics Electric Boat Company built a quarter-scale version of a Virginia-class submarine dubbed Large Scale Vehicle II (LSV II) Cutthroat. The vehicle was designed as an affordable test platform for new technologies.[25][26]

The Virginia class is built through an industrial arrangement designed to maintain both GD Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding, the only two U.S. shipyards capable of building nuclear-powered submarines.[27] Under the present arrangement, the Newport News facility builds the stern, habitability, machinery spaces, torpedo room, sail, and bow, while Electric Boat builds the engine room and control room. The facilities alternate work on the reactor plant as well as the final assembly, test, outfit, and delivery.

O'Rourke wrote in 2004 that, "Compared to a one-yard strategy, approaches involving two yards may be more expensive but offer potential offsetting benefits."[28] Among the claims of "offsetting benefits" that O'Rourke attributes to supporters of a two-facility construction arrangement is that it "would permit the United States to continue building submarines at one yard even if the other yard is rendered incapable of building submarines permanently or for a sustained period of time by a catastrophic event of some kind", including an enemy attack.

In order to get the submarine's price down to $2 billion per submarine in FY-05 dollars, the Navy instituted a cost-reduction program to shave off approximately $400 million of each submarine's price tag. The project was dubbed "2 for 4 in 12," referring to the Navy's desire to buy two boats for $4 billion in FY-12. Under pressure from Congress, the Navy opted to start buying two boats per year in FY-11, meaning that officials would not be able to get the $2 billion price tag before the service started buying two submarines per year. However, program manager Dave Johnson said at a conference on 19 March 2008 that the program was only $30 million away from achieving the $2 billion price goal, and would reach that target on schedule.[29]

The Virginia-class Program Office received the David Packard Excellence in Acquisition Award in 1996, 1998, 2008, "for excelling in four specific award criteria: reducing life-cycle costs; making the acquisition system more efficient, responsive, and timely; integrating defense with the commercial base and practices; and promoting continuous improvement of the acquisition process".[30]

In December 2008, the Navy signed a $14 billion contract with General Dynamics and Northrop Grumman to supply eight submarines. The contract required the delivery of one submarine in each of fiscal 2009 and 2010, and two submarines on each of fiscal 2011, 2012, and 2013.[31] This contract was designed to bring the Navy's Virginia-class fleet to 18 submarines. In December 2010, the United States Congress passed a defense authorization bill that expanded production to two subs per year.[32] Two submarine-per-year production resumed on 2 September 2011 with commencement of Washington (SSN-787) construction.[33]

On 21 June 2008, the Navy christened USS New Hampshire, the first Block II submarine. This boat was delivered eight months ahead of schedule and $54 million under budget. Block II boats are built in four sections, compared to the ten sections of the Block I boats. This enables a cost saving of about $300 million per boat, reducing the overall cost to $2 billion per boat and the construction of two new boats per year. Beginning in 2010, new submarines of this class were to have included a software system that can monitor and reduce their electromagnetic signatures when needed.[34]

The first full-duration six-month deployment was successfully carried out from 15 October 2009 to 13 April 2010.[35] Authorization of full-rate production and the declaration of full operational capability was achieved five months later.[36] In September 2010, it was found that urethane tiles, applied to the hull to damp internal sound and absorb rather than reflect sonar pulses, were falling off while the subs were at sea.[37] Admiral Kevin McCoy announced that the problems with the Mold-in-Place Special Hull Treatment for the early subs had been fixed in 2011, then Minnesota was built and found to have the same problem.[38]

Professor Ross Babbage of the Australian National University has called on Australia to buy or lease a dozen Virginia-class submarines from the United States, rather than locally build 12 replacements for its Collins-class submarines.[39]

In 2013, just as two-per-year sub construction was supposed to commence, Congress failed to resolve the United States fiscal cliff, forcing the Navy to attempt to "de-obligate" construction funds.[40]

Innovations[]

The Virginia class incorporates several innovations not found in previous US submarine classes.[22]

Technology barriers[]

Because of the low rate of Virginia production, the Navy entered into a program with DARPA to overcome technology barriers to lower the cost of attack submarines so that more could be built, to maintain the size of the fleet.[41]

These include:[42]

- Propulsion concepts not constrained by a centerline shaft.

- Externally stowed and launched weapons (especially torpedoes).

- Conformal alternatives to the existing spherical sonar array.

- Technologies that eliminate or substantially simplify existing submarine hull, mechanical, and electrical systems.

- Automation to reduce crew workload for standard tasks

Unified Modular Masts[]

Virginia class subs are the first class where all masts share common design - the Universal Modular Mast (UMM) - designed by L3 KEO[43] (previously Kollmorgen).[44][45] Shared components have been maximized and some design choices are also shared between different masts. The first UMM was installed on USS Memphis, a Los Angeles-class submarine.[46] The UMM is an integrated system for housing, erecting, and supporting submarine mast-mounted antennas and sensors.[47] The UMMs are the following.[48]

- Snorkel mast

- Two photonic masts[48]

- Two communication masts[48]

- One or two high-data-rate satellite communication (SATCOM) masts,[49] built by Raytheon,[50] enabling communication at Super High Frequency (for downlink) and Extremely High Frequency (for uplink) range[50][51]

- Radar mast (carrying AN/BPS-16 surface search and navigation radar)[52]

- Electronic warfare mast (AN/BLQ-10 Electronic Support Measures) used to detect, analyze, and identify both radar and communication signals from ships, aircraft, submarines, and land-based transmitters[53][54][55]

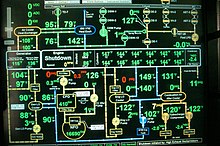

Photonics masts[]

The Virginia class is the first to utilize photonic sensors instead of a traditional periscope. The class is equipped with high-resolution cameras, along with light-intensification and infrared sensors, an infrared laser rangefinder, and an integrated Electronic Support Measures (ESM) array. Two redundant sets of these sensors are mounted on two photonics masts[22] located outside the pressure hull. Signals from the masts' sensors are transmitted through optical fiber data lines through signal processors to the control center.[56] Visual feeds from the masts are displayed on liquid-crystal display interfaces in the command center.[15]

The design of earlier optical periscopes required them to penetrate the pressure hull, reducing the structural integrity of the pressure hull as well as increasing the risk of flooding, and also required the submarine's control room to be located directly below the sail/fin.[57] Implementation of photonics masts (which do not penetrate the pressure hull) enabled the submarine control room to be relocated to a position inside the pressure hull which is not necessarily directly below the sail.[48]

The current photonics masts have a visual appearance so different from the ordinary periscopes that when the submarine is detected, it can be distinctly identified as a Virginia-class vessel. As a result, current photonic masts will be replaced with Low-Profile Photonics Masts (LPPM) which resemble traditional submarine periscopes more closely.[48]

In the future, a non-rotational Affordable Modular Panoramic Photonics Mast may be fitted, enabling the submarine to obtain a simultaneous 360° view of the sea surface.[58][59]

Propulsor[]

In contrast to a traditional bladed propeller, the Virginia class uses pump-jet propulsors (built by BAE Systems),[60] originally developed for the Royal Navy's Swiftsure-class submarines.[61] The propulsor significantly reduces the risks of cavitation, and allows quieter operation.

Improved sonar systems[]

Sonar arrays aboard Virginia-class submarines have an "Open System Architecture" (OSA) which enables rapid insertion of new hardware and software as they become available. Hardware upgrades (dubbed Technology Insertions) are usually carried out every four years, while software updates (dubbed Advanced Processor Builds) are carried out every two years. Virginia-class submarines feature several types of sonar arrays.[62]

- BQQ-10 bow-mounted spherical active/passive sonar array[62][63] (Large Aperture Bow (LAB) sonar array from SSN-784 onwards)

- A wide aperture lightweight fiber optic sonar array, consisting of three flat panels mounted low along either side of the hull[64]

- Two high frequency active sonars mounted in the sail and bow. The chin-mounted (below the bow) and sail-mounted high frequency sonars supplement the (spherical/LAB) main sonar array, enabling safer operations in coastal waters, enhancing under-ice navigation, and improving anti-submarine warfare performance.[65][66]

- Low-Cost Conformal Array (LCCA) high frequency sonar, mounted on both sides of the submarine's sail. Provides coverage above and behind the submarine.[67]

Virginia-class submarines are also equipped with a low frequency towed sonar array and a high frequency towed sonar array.[68]

- TB-16 or TB-34 fat line tactical towed sonar array[69][70]

- TB-29 or TB-33 thin line long-range search towed sonar array[69][70]

Rescue equipment[]

- Submarine Escape Immersion Equipment MK11 suit(s) – enable ascent from a sunken submarine (maximum ascent depth 600 feet)[62][71]

- Lithium hydroxide canisters that remove carbon dioxide from the submarine's atmosphere[62]

- Submarine Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (SEPIRB)[72][73]

Virginia Payload Module[]

The Block III submarines have two multipurpose Virginia Payload Tubes (VPT) replacing the dozen single purpose cruise missile launch tubes.[74]

The Block V submarines built from 2019 onward will have an additional Virginia Payload Module (VPM) mid-body section, increasing their overall length. The VPM will add four more VPTs of the same diameter and greater height, located on the centerline, carrying up to seven Tomahawk missiles apiece, that would replace some of the capabilities lost when the SSGN conversion Ohio-class submarines are retired from the fleet.[28][75] Initially eight payload tubes/silos were planned[75] but this was later rejected in favour of four tubes installed in a 70-foot (21 m) long module between the operations compartment and the propulsion spaces.[75][76][77]

The VPM could potentially carry (non-nuclear) medium-range ballistic missiles. Adding the VPM would increase the cost of each submarine by $500 million (2012 prices).[78] This additional cost would be offset by reducing the total submarine force by four boats.[79] More recent reports state that as a cost reduction measure the VPM would carry only Tomahawk SLCM and possibly unmanned undersea vehicles (UUV) with the new price tag now estimated at $360–380 million per boat (in 2010 prices). The VPM launch tubes/silos will reportedly be similar in design to the ones planned for the Ohio-class replacement.[80][81] In July 2016 General Dynamics was awarded $19 million for VPM development.[82] In February 2017 General Dynamics was awarded $126 million for long lead time construction of Block V submarines equipped with VPM.[83]

The VPM was designed by BWX Technologies[84] (the same company also designs the missile tubes for the Columbia-class submarine),[85] however, manufacture is undertaken by BAE Systems.[86]

High-energy laser weapon[]

According to open-source budget documents, Virginia-class submarines are planned to be equipped with a high-energy laser weapon likely to be incorporated into the photonics mast and have a power output of 300–500 kilowatts, based on the submarine's 30 megawatts reactor capacity.[87][88]

Other improved equipment[]

- Optical fiber fly-by-wire Ship Control System replaces electro-hydraulic systems for control surface actuation.

- Command and control system module (CCSM) built by Lockheed Martin.[6][89]

- The auxiliary generator is powered by a Caterpillar model 3512B V-12 marine diesel engine. This replaced the Fairbanks-Morse diesel engine, which would not fit in Virginia's auxiliary machinery room.

- Modernized version of the AN/BSY-1 integrated combat system[12] designated AN/BYG-1 (previously designated CCS Mk2) and built by General Dynamics AIS (previously Raytheon).[90][91] AN/BYG-1 integrates the submarine Tactical Control System (TCS) and Weapon Control System (WCS).[92][93]

- USS California was the first Virginia-class submarine with the advanced electromagnetic signature reduction system built into it, but this system is being retrofitted into the other submarines of the class.[94]

- Integral 9-man lock-out chamber.[95]

Specifications[]

- Builders: General Dynamics Electric Boat and HII Newport News Shipbuilding

- Length: 377 ft (114.91 m) [Block V: 460 ft (140.2 m)]

- Beam: 34 ft (10.36 m)

- Displacement: 7,800 long tons (7,900 t) [Block V: 10,200 long tons 10,200 long tons (10,400 t)

- Payload: 40 weapons, special operations forces, unmanned undersea vehicles, Advanced SEAL Delivery System (ASDS) [Block V: 40 Tomahawk cruise missiles]

- Propulsion: S9G nuclear reactor delivering 40,000 shaft horsepower.[96] Nuclear core life estimated at 33 years.[97] Nuclear fuel manufactured by BWX Technologies.[98][99]

- Test depth: greater than 800 ft (240 m), allegedly around 1,600 feet (490 m).[95]

- Speed: Greater than 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph),[100] allegedly up to 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph)[101][102][103]

- Planned cost: about US$1.65 billion each (based on FY95 dollars, 30-boat class and two boat/year build-rate)

- Actual cost: US$1.5 billion (in 1994 prices), US$2.6 billion (in 2012 prices)[104][105]

- Annual operating cost: $50 million per unit[106]

- Crew: 120 enlisted and 14 officers

- Armament: 12 VLS & four torpedo tubes, capable of launching Mark 48 torpedoes, UGM-109 Tactical Tomahawks, Harpoon (missile)s[107] and the new advanced mobile mine when it becomes available.[citation needed] Block V boats will have the additional VPM module which contains four large diameter tubes which can accommodate seven Tomahawk cruise missiles each. This would increase the total number of torpedo-sized weapons (such as Tomahawks) carried by the Virginia-class design from about 37 to about 65—an increase of about 76%.[108]

- Decoys: Acoustic Device Countermeasure Mk 3/4[109]

Boats[]

Block I[]

Block I involved 4 boats and modular construction techniques were incorporated during construction.[110] Earlier submarines (e.g., Los Angeles-class SSNs) were built by assembling the pressure hull and then installing the equipment via cavities in the pressure hull. This required extensive construction activities within the narrow confines of the pressure hull which was time-consuming and dangerous. Modular construction was implemented in an effort to overcome these problems and make the construction process more efficient. Modular construction techniques incorporated during construction include constructing large segments of equipment outside the hull. These segments (dubbed rafts) are then inserted into a hull section (a large segment of the pressure hull). The integrated raft and hull section form a module which, when joined with other modules, forms a Virginia-class submarine.[111] Block I boats were built in 10 modules with each submarine requiring roughly 7 years (84 months) to build.[112]

Block II[]

Block II involved 6 boats; they were built in four sections rather than ten sections, saving about $300 million per boat. Block II boats (excluding SSN-778) were also built under a multi-year procurement agreement as opposed to a block-buy contract in Block I, enabling savings in the range of $400 million ($80 million per boat).[28][21] As a result of improvements in the construction process, New Hampshire was US$500 million cheaper, required 3.7 million fewer labor hours to build (25% less), thus shortening the construction period by 15 months (20% less) compared to Virginia.[111]

Block III[]

SSN-784 through SSN-791 (8 boats) make up the Third Block or "Flight" and began construction in 2009. Block III subs feature a revised bow with a Large Aperture Bow (LAB) sonar array, as well as technology from Ohio-class SSGNs (2 VLS tubes each containing 6 missiles).[113] The horseshoe-shaped LAB sonar array replaces the spherical main sonar array which has been used on all U.S. Navy SSNs since 1960.[21][114][115] The LAB sonar array is water-backed—as opposed to earlier sonar arrays which were air-backed—and consists of a passive array and a medium-frequency active array.[116] Compared to earlier Virginia-class submarines about 40% of the bow has been redesigned.[clarification needed][117]

South Dakota (SSN-790) will be equipped with a new propulsor,[118] possibly the Hybrid Multi-Material Rotor (HMMR),[119][120] developed by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).[118] The Hybrid Multi-Material Rotor program is an attempt to improve the design and manufacturing process of submarine propellers with an aim of reducing the cost and weight of the propeller/rotor as well as improving overall acoustic performance.[118][119][120]

Block IV[]

Block IV involved 10 boats. In 2013, execution of this 10-submarine contract was put in doubt by budget sequestration in 2013.[121] The most costly shipbuilding contract in history was awarded on 28 April 2014 as prime contractor General Dynamics Electric Boat took on a $17.6 billion contract for ten Block IV Virginia-class attack submarines. The main improvement over the Block III is the reduction of major maintenance periods from four to three, increasing each boat's total lifetime deployments by one.[122]

The long-lead-time materials contract for SSN-792 was awarded on 17 April 2012, with SSN-793 and SSN-794 following on 28 December 2012.[123][124] The U.S. Navy has awarded General Dynamics Electric Boat a $208.6 million contract modification for the second fiscal year (FY) 14 Virginia-class submarine, SSN-793, and two FY 15 submarines, SSN-794 and SSN-795. With this modification, the overall contract is worth $595 million.[125] Block IV consists of 10 submarines.[126]

Block V[]

Block V involves 10 boats and may incorporate the Virginia Payload Module (VPM), which would give guided-missile capability when the SSGNs are retired from service.[127] The Block V subs are expected to triple the capacity of shore targets for each boat.[10] Construction on the first two boats of this block was expected to begin in 2019 but was pushed back to 2020, with contracts for long lead time material for SSN-802 and SSN-803 being awarded to General Dynamic's Electric Boat.[128][129] HII Newport News Shipbuilding was awarded a long-lead materials contract for two Block V boats in 2017, the first Block Vs for the company.[130]

On 2 December 2019, the Navy announced an order for nine new Virginia-class submarines – eight Block Vs and one Block IV – for a total contract price of $22 billion with an option for a tenth boat.[131] The Block V subs were confirmed to have an increased length, from 377 ft to 460 ft, and displacement, from 7,800 tons to 10,200 tons. This would make the Block V the second-largest US submarine, behind only the Ohio-class (at 560 ft).[2]

On 22 March 2021, the U.S. Navy added a 10th ship in Block V series of the Virginia-class attack submarine, issuing a $2.4 billion adjustment on a contract initially awarded in December 2019. This brings the total cost of the contract with prime contractor General Dynamics Electric Boat to $24.1 billion. The net increase for the contract is $1.89 billion, according to a General Dynamics release. Huntington Ingalls Industries' Newport News shipyard is the partner yard in the program.[132]

List of boats[]

| Name | Hull number | Builder | Ordered | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virginia | SSN-774 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 30 September 1998 | 2 September 1999 | 16 August 2003 | 23 October 2004 | In service[133] |

| Texas | SSN-775 | Newport News Shipbuilding, Newport News | 12 July 2002 | 9 April 2005 | 9 September 2006 | In service[134] | |

| Hawaii | SSN-776 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 27 August 2004 | 17 June 2006 | 5 May 2007 | In service[135] | |

| North Carolina | SSN-777 | Newport News Shipbuilding, Newport News | 22 May 2004 | 5 May 2007 | 3 May 2008 | In service[136] | |

| New Hampshire | SSN-778 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 14 August 2003 | 30 April 2007 | 21 February 2008 | 25 October 2008[137] | In service |

| New Mexico | SSN-779 | Newport News Shipbuilding, Newport News | 12 April 2008 | 18 January 2009 | 27 March 2010[138] | In service | |

| Missouri | SSN-780 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 27 September 2008 | 20 November 2009 | 31 July 2010[139][140] | In service | |

| California | SSN-781 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 1 May 2009 | 14 November 2010 | 29 October 2011[141] | In service | |

| Mississippi | SSN-782 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 9 June 2010 | 10 December 2011 | 2 June 2012[142] | In service | |

| Minnesota | SSN-783 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 20 May 2011 | 10 November 2012 | 7 September 2013[143][144] | In service | |

| North Dakota | SSN-784 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 14 August 2003 | 11 May 2012[145] | 15 September 2013[145] | 25 October 2014[145] | In service[145] |

| John Warner | SSN-785 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 22 December 2008 | 16 March 2013[146] | 10 September 2014[146] | 1 August 2015[146] | In service[146] |

| Illinois | SSN-786 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 2 June 2014[147] | 8 August 2015[147] | 29 October 2016[148] | In service[148] | |

| Washington | SSN-787 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 22 November 2014[149] | 25 March 2016[149] | 7 October 2017[150] | In service | |

| Colorado | SSN-788 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 7 March 2015[151] | 29 December 2016 | 17 March 2018[152] | In service | |

| Indiana | SSN-789 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 16 May 2015[153] | 9 June 2017 | 29 September 2018[154] | In service | |

| South Dakota | SSN-790 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 4 April 2016[155] | 14 October 2017 | 2 February 2019[156] | In service | |

| Delaware | SSN-791 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 30 April 2016[157] | 17 December 2018 | 4 April 2020[158] | In service. | |

| Vermont | SSN-792 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 28 April 2014 | c. February 2017 | 20 October 2018 | 18 April 2020 | In service.[159][160][161] |

| Oregon | SSN-793 | 8 July 2017[162] | 5 October 2019 | Launched[163][164] | |||

| Montana | SSN-794 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 16 May 2018[165] | February 2021[166] | Launched[167] | ||

| Hyman G. Rickover | SSN-795 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 11 May 2018 | 31 July 2021[168] | Launched[169][170][171][172] | ||

| New Jersey | SSN-796 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 25 March 2019 | Under construction[173][174] | |||

| Iowa | SSN-797 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 20 August 2019 | Under construction[175] | |||

| Massachusetts | SSN-798 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | 11 Dec 2020[176] | Under construction[177] | |||

| Idaho | SSN-799 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | 24 August 2020 | Under construction[178] | |||

| Arkansas | SSN-800 | Huntington Ingalls Industries, Newport News | Under construction[179] | ||||

| Utah | SSN-801 | General Dynamics Electric Boat, Groton | Under construction[180] | ||||

| Oklahoma | SSN-802 | Electric Boat (long-lead materials only) Full build contract: TBA | 16 February 2017 (long-lead material only)[128][129] | On order[181] | |||

| Arizona | SSN-803 | On order[182] | |||||

| Barb[183] | SSN-804 | ||||||

| Tang[184] | SSN-805 | ||||||

| Wahoo[184] | SSN-806 | ||||||

| Silversides | SSN-807 | Announced[185] | |||||

| Unnamed | SSN-808 | ||||||

| Unnamed | SSN-809 | ||||||

| Unnamed | SSN-810 | ||||||

| Unnamed | SSN-811 | ||||||

Future acquisitions[]

The Navy plans to acquire at least 34 Virginia-class submarines,[186][187] however, more recent data provided by the Naval Submarine League (in 2011) and the Congressional Budget Office (in 2012) seems to imply that more than 30 submarines may eventually be built. The Naval Submarine League believes that up to 10 Block V boats will be built.[19][188] The same source also states that 10 additional submarines could be built after Block V submarines, with 5 in the so-called Block VI and 5 in Block VII, largely due to the delays experienced with the "Improved Virginia". These 20 submarines (10 Block V, 5 Block VI, 5 Block VII) would carry VPM bringing the total number of Virginia-class submarines to 48 (including the 28 submarines in Blocks I, II, III and IV). The CBO in its 2012 report states that 33 Virginia-class submarines will be procured in the 2013–2032 timeframe,[4] resulting in 49 submarines in total since 16 were already procured by the end of 2012.[189] Such a long production run seems unlikely but another naval program, the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, is still ongoing even though the first vessel was procured in 1985.[190][191] However, other sources believe that production will end with Block V.[192] In addition, data provided in CBO reports tends to vary considerably compared to earlier editions.[4]

Block VI submarines include an organic ability to employ seabed warfare equipment.[193]

SSN(X)/Improved Virginia[]

Initially dubbed Future Attack Submarine[194] and Improved Virginia class in Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports,[4] the SSN(X) or Improved Virginia-class submarines will be an evolved version of the Virginia class.[4]

In late 2014, the Navy began early preparation work on the SSN(X). It was planned that the first submarine would be procured in 2025. However, their introduction (i.e., procurement of the first submarine) has been pushed back to 2033/2034.[4][195] The long-range shipbuilding plan is for the new SSN to be authorized in 2034, and become operational by 2044 after the last Block VII Virginia is built. Roughly a decade will be spent identifying, designing, and demonstrating new technologies before an analysis of alternatives is issued in 2024. An initial small team has been formed to consult with industry and identify the threat environment and technologies the submarine will need to operate against in the 2050-plus timeframe. One area already identified is the need to integrate with off-board systems so future Virginia boats and the SSN(X) can employ networked, extremely long-ranged weapons. A torpedo propulsion system concept from the Pennsylvania State University could allow a torpedo to hit a target 200 nmi (230 mi; 370 km) away and be guided by another asset during the terminal phase. Targeting information might also come from another platform like a patrol aircraft or an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) launched from the submarine.[196] Researchers have identified a quieter advanced propulsion system and the ability to control multiple unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) at once as key SSN(X) components. The future submarines will operate through the end of the 21st century, and potentially into the 22nd century.[197] New propulsion technology, moving beyond the use of a rotating mechanical device to push the boat through the water, could come in the form a biomimetic propulsion system that would eliminate noise-generating moving parts like the drive shaft and the spinning blades of the propulsor.[198]

Potential exports[]

On 16 September 2021, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced that Australia had cancelled the Shortfin Barracuda-class submarine in favor of a nuclear-powered submarine based on the latest Block V design of the Virginia-class submarine.[199] [200]

In a trilateral deal with the UK, the US and Australia known as AUKUS, the Royal Australian Navy will acquire eight nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarines.[201] Eight submarines will be built at a state-owned Australian Submarine Corporation (ASC) shipyard in Adelaide, Australia.[202] The US offers nuclear reactor, armaments, sonar suite and submarine hull to Australia and the UK to provide atomic fuel rods and associated facilities to support civil nuclear propulsion for Royal Australian Navy.[203][204]

See also[]

- List of submarine classes of the United States Navy

- List of submarines of the United States Navy

- List of submarine classes in service

- Submarines in the United States Navy

- Cruise missile submarine

- List of current United States Navy ships

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. 29 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "U.S. Navy Orders New Block of Attack Submarines". maritime-executive.com. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ragheb, Magdi (18 September 2021), Tsvetkov, Pavel (ed.), "Nuclear Naval Propulsion", Nuclear Power - Deployment, Operation and Sustainability, ISBN 978-953-307-474-0

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2013 Shipbuilding Plan" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. July 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ O'Rouke, Ronald (17 May 2017). "Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017 – via Federation of American Scientists.

- ^ "History of Ships Named for the State of North Carolina - Battleships NC". Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "Submarine surge: Why the Navy plans 32 new attack subs by 2034". Warrior Maven. 28 March 2019. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Osborn, Kris (12 February 2014). "Navy Considers Future After Virginia-class Subs". Defensetech.org. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson, Loren (6 May 2014). "Five Reasons Virginia-Class Subs Are the Face of Future Warfare". Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "General Dynamics Electric Boat - History". gdeb.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "SSN-774 Virginia class". Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Navy Report on New Attack Submarine (Senate - July 21, 1992)". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Schank, John F.; Ip, Cesse; Lacroix, Frank W.; Murphy, Robert E.; Arena, Mark V.; Kamarck, Kristy N.; Lee, Gordon T. (2011). "RAND Corporation-Virginia Case Study". Learning from Experience: 61–92. ISBN 9780833058966. JSTOR 10.7249/j.ctt3fh0zm.13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Graves, Barbara; Whitman, Edward (Winter 1999). "Virginia-class: America's Next Submarine". Undersea Warfare. US Navy. 1 (2). Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Submarine Industrial Base Council". Submarinesuppliers.org. 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Schank, John F.; Arena, Mark V.; DeLuca, Paul; Riposo, Jessie; Curry, Kimberly; Weeks, Todd; Chiesa, James (2007). Sustaining U.S. Nuclear Submarine Design Capabilities (PDF). National Defense Research Institute. ISBN 978-0-8330-4160-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Naval Submarine League". Navalsubleague.com. 27 September 2012. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Jim (Winter 2011). "Double Vision: Planning to Increase Virginia-Class Production". Undersea Warfare. US Navy (43). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Butler, John D., RAdm (ret) (June 2011). "The Sweet Smell of Acquisition Success". Proceedings. U.S. Naval Institute. 137 (6/1, 300). Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Baker, A. D. III (1998). Combat Fleets of the World, 1998–1999. USA. p. 1005. ISBN 978-1-55750-111-0.

- ^ "Statement of The Honorable Duncan Hunter, Chairman, Subcommittee on Military Procurement, Submarine Force Structure and Modernization". Federation of American Scientists Military Analysis Network. 27 June 2000. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Statement of Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in National Defense Congressional Research Service before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Projection Forces Hearing on Navy Force Architecture and Ship Construction". 10 March 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ "AUV System Spec Sheet Cutthroat LSV-2 configuration". Antonymous Undersea Vehicle Applications Center. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Fox, David M., CDR (Spring 2001). "Small Subs Provide Big Payoffs for Submarine Stealth". Undersea Warfare. 3 (3). Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "SSN-774 Virginia-class NSSN New Attack Submarine". Federation of American Scientists. 19 January 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c O'Rourke, Ronald (26 March 2015). Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Cost reduction". Retrieved 25 March 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Navy's Virginia Class Program Recognized for Acquisition Excellence" (Press release). Washington, DC: Team Submarines Public Affairs. 8 November 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "General Dynamics And Northrop Awarded Submarine Deal". The New York Times. 22 December 2008.[dead link]

- ^ McDermott, Jennifer (23 December 2010). "House, Senate ok defense bill for 2011; sub plan stays on track". The Day. New London, Connecticut. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Construction Begins on SSN 787; Navy Transitions to Building Two Virginia Class Submarines Per Year" (Press release). Washington, DC: NAVSEA – Naval Sea Systems Command. 8 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Pike, John. "SSN-774 Virginia-class NSSN New Attack Submarine". Global Security. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Communication, Mass. "VARFD.aspx". Public.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Virginia Class Program Reaches Major Milestone" (Press release). Washington, DC: United States Navy. 10 October 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Hooper, Craig (6 September 2010). "Virginia Class: When does hull coating separation endanger the boat?". Next Navy. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Hooper, Craig (7 November 2013). "The Virginia Peel: Why are $2 Billion Dollar Subs Losing Their Skin?". Next Navy. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Mahnken, Tom (9 February 2011). "Growing concern down under". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Christopher Cavas (2 March 2013). "U.S. Navy Sets Budget-cutting Plans in Motion". Blogs.defensenews.com. Retrieved 22 July 2015.[dead link]

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (23 June 2005). Navy Ship Acquisition: Options for Lower-Cost Ship Designs — Issues for Congress (PDF) (Report). RL32914. Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Tango Bravo". Strategic Technology Office. DARPA. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ "Submarine Imaging". .l-3com.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "L-3 Completes Acquisition of Kollmorgen Electro-Optical" (Press release). L-3com.com. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "L-3 completes $210M Kollmorgen acquisition". Optics.org. SPIE Europe Ltd. 8 February 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Photonics Mast Program" (PDF). L-3 KEO. 20 March 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Navy: Vision ... Presence ... Power". US Navy. 30 July 1998. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Sea Power" (February/March 2015). Navy League of the United States. 19 February 2015: 22–25. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ RADM Fages' 2000 Testimony (Speech). Chief of Naval Operations, Submarine Warfare Division. 27 June 2000. Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Raytheon to Produce SATCOM System for New Virginia Class Submarine; Contract Valued at $29.4 Million" (Press release). Raytheon. 28 July 2000. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Factsheets : Advanced Extremely High Frequency System". Air Force Space Command. 25 March 2015. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "AN/BPS-15/16 Radar". Fact File. US Navy. 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Ships, Sensors, and Weapons". 3 (3). US Navy. Spring 2001. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Phelps, William (29 October 2002). AN/BLQ-10(V): Submarine Electronic Warfare Support for the 21st Century (PDF). 39th Annual AOC International Symposium and Convention. Nashville, Tennessee: Association of Old Crows. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "AN/BLQ-10 Submarine Electronic Warfare Support System" (PDF). dote.osd.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Paschoa, Claudio (11 September 2014). "UMM Photonics Mast for Virginia-class Attack". Marinetechnologynews.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Holian, Thomas (Fall 2004). "Eyes from the Deep: A History of U.S. Navy Submarine Periscopes". Undersea Warfare. US Navy. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Affordable Modular Panoramic Photonics Mast". Office of Naval Research. October 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Affordable Modular Panoramic Photonics". Office of Naval Research. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "BAE Systems Delivers First U.S. Navy Submarine Propulsor from Louisville Facility, Receives Additional $24.3 Million Contract" (Press release). BAE Systems. 1 June 2012. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Hool, Jack; Nutter, Keith (2003). Damned Un-English Machines, a history of Barrow-built submarines. Tempus. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7524-2781-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "US Navy Program Guide 2013" (PDF). US Navy. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "APPENDIX C Exercise and Sonar Type Descriptions" (PDF). December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Submarine Hull Arrays". Northropgrumman.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Special Purpose Sonar". Ultra Electronics Ocean Systems. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Moreavek, Leonard, LTJG; Brudner, T.J (1999). "USS Asheville Leads the Way in High Frequency Sonar". Undersea Warfare. 1 (3). Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Keller, John (25 March 2012). "Lockheed Martin to provide Navy submarines with 360-degree situational-awareness sail-mounted sonar". Military & Aerospace Electronics. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Virginia Class Attack Submarine - SSN". Military.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Acoustic Rapid Commercial Off‑the‑Shelf (COTS) Insertion (A-RCI) and AN/BYG‑1 Combat Control System" (PDF). dote.osd.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Acoustic Rapid Commercial Off-the-Shelf (COTS) Insertion for Sonar AN/BQQ-10 (V) (A-RCI)" (PDF). GlobalSecurity.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Crafty Devil - Survitec Group. "Products » RFD Beaufort - SEIE MK11". Survitec Group. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Ultra Electronics Ocean Systems - Underwater Communications". Ultra Electronics. Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ SSN 774 Class Guard Book - Disabled Submarine Survival Guide - Aft Escape Trunk (Logistics Escape Truck) (PDF). US Navy. 29 March 2012. Card 6I. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Freedberg Jr., Sydney J. (16 April 2014). "Navy Sub Program Stumbles: SSN North Dakota Delayed By Launch Tube Troubles". Breaking Defense. Breaking Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hasslinger, Karl, CAPT, USN (ret); Pavlos, John (Winter 2012). "The Virginia Payload Module: A Revolutionary Concept for Attack Submarines". Undersea Warfare. US Navy (47). Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Navy Selects Virginia Payload Module Design Concept". USNI News. U. S. Naval Institute. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ "Document: PEO Subs Overview of U.S. Navy Undersea Programs". USNI News. U.S. Naval Institute. 24 October 2013. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ Grossman, Elaine M. (1 August 2012). "U.S. Senate Panel Curbs Navy Effort to Add Missiles to Attack Submarines". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Global Security Newswire. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Cavas, Christopher P. (4 February 2013). "Navy cuts fleet goal to 306 ships". Navy Times. Retrieved 6 February 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ross, Robert T. (17 May 2013). "Lower Ohio-Class Replacement Cost Tied To VA-Class Multiyear Deal: Could Achieve 8 To 15 Percent Savings". State of Connecticut, Office of Military Affairs. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Osborn, Kris (28 January 2014). "Navy, Electric Boat Test Tube-Launched Underwater Vehicle". Groton, Connecticut: Defense Tech. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "General Dynamics Awarded $19 Million by U.S. Navy for Virginia Payload Module Development". 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ "General Dynamics Awarded $126 Million by U.S. Navy for Virginia-Class Block V Long Lead Time Material". 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ "BWX Technologies to Develop Payload Tubes for Virginia-class Submarines". Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "BWXT to manufacture additional CMC tube assemblies for US Columbia-class submarines". 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "BAE Systems ramps up for Virginia-class submarine payload module launch tube production". Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "The Navy Is Arming Nuclear Subs With Lasers. No One Knows Why". Popular Mechanics. 4 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ "The Navy Is Arming Attack Submarines With High Energy Lasers". Forbes. 9 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Kearney, Tom, CDR (Spring 2001). "Status Report: PCU Virginia (SSN-774)". Undersea Warfare. US Navy. 3 (3). Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Raytheon Delivers Submarine Combat System to Royal Australian Navy". Raytheon. 30 January 2006. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "General Dynamics To Upgrade Submarine Weapons Control Systems". Defense Industry Daily. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "AN/BYG-1 Submarine Tactical Control System (TCS)". General Dynamics. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "General Dynamics continues project to upgrade submarine electronics with COTS computers". Military & Aerospace Electronics. 27 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "GAO-09-326SP" (PDF). Government Accounting Office. March 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "USS Virginia SSN-774-A New Steel Shark at Sea". Applied Technology Institute. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Ragheb, M. (11 November 2010). Nuclear Marine Propulsion (PDF) (Thesis). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Naval Reactors". Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "HOW AMERICAN, RUSSIAN, AND CHINESE NUCLEAR-POWERED SUBMARINES COMPARE". 2015. Archived from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "US Virginia Class vs Russian Yasen Class Submarine Warfare - Who Wins?". 2017. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Kit Bonner, Carolyn Bonner (2007). Modern Warships. ISBN 9781616732608.

- ^ Ted Kennedy; John Conyers (20 October 1994). "Lessons of Prior Programs May Reduce New Attack Submarine Cost Increases and Delays" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Virginia Class Sub Program Wins Acquisition Award". Defenseindustrydaily.com. 20 November 2008. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Cowan, Simon (5 November 2012). "Facts favour nuclear-powered submarines". Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "WEST: U.S. Navy Anti-Ship Tomahawk Set for Surface Ships, Subs Starting in 2021". Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Acoustic Countermeasures". Ultra Electronics Ocean Systems. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Patani, Arif (24 September 2012). "Next Generation Ohio-Class". Navy Live. US Navy. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holmander, John D.; Plante, Thomas (Winter 2011). "The Four-Module Build Plan: The Second Decade of Virginia-class Construction Gets Better". Undersea Warfare (43). US Navy. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Johnson, David C., RDML (sel.); Drakeley, George M.; Smith, George M. (23 September 2008). Engineering the Solution: Virginia-Class Submarine Cost Reduction (PDF). Engineering the Total Ship (ETS) 2008. Falls Church, Virginia: American Society of Naval Engineers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ "Virginia Block III: The Revised Bow". Defense Industry Daily. 21 December 2008. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ "Submarine Technology Through the Years". Chief of Naval Operations, Submarine Warfare Division, Submarine History. US Navy. 19 July 1997. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Lambert, Paul. "Official USS Tullibee (SSN 597) Web Site - USS Tullibee History". Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ "North Dakota (SSN-784)". NavSource Online: Submarine Photo Archive. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ LaGrone, Sam (17 April 2014). "Navy Delays Commissioning of Latest Nuclear Attack Submarine". USNI News. U.S. Naval Institute. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Freedburg, Sydney (12 September 2013). "Navy To HASC: We're About To Sign Sub Deals We Can't Pay For". Breaking Defense. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ LaGrone, Sam (28 April 2014). "U.S. Navy Awards 'Largest Shipbuilding Contract' in Service History". USNI News. U.S. Naval Institute. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ "Contracts" (Press release). U.S. Department of Defense. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Contracts" (Press release). U.S. Department of Defense. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "General Dynamics Awarded $209 Million for Future Virginia-class Submarines" (Press release). Groton, Connecticut: General Dynamics - Electric Boat. 1 July 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Navy Fact Sheet Attack Submarines - SSN". Naval Sea Systems Command. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Virginia Payload Module (VPM)". General Dynamics - Electric Boat. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "General Dynamics Awarded $126 Million by US Navy for Virginia-class Block V Long Lead Time Material". gd.com. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "General Dynamics Electric Boat archives: 26 February 2017 Block V press release". gdeb.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Huntington Iingalls Industries reports first quarter 2017 results". 4 May 2017. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Popular Mechanics

- ^ David Larter (22 March 2021). "US Navy inks deal for a tenth Virginia-class submarine". Defense News.

- ^ Piggott, Mark O. (24 October 2004). "Commissioning of USS Virginia Ushers in New Era of Undersea Warfare" (Press release). Norfolk, Virginia: Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Shoffner, Scott (5 September 2006). "Texas Arrives in Galveston" (Press release). Galveston, Texas: Commander, Naval Submarine Force, Atlantic Fleet Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Elinson, Ira J. (5 May 2007). "Navy Commissions USS Hawaii" (Press release). Groton, Connecticut: Naval Submarine Base New London Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Zeldis, Jennifer, LT (4 May 2008). "USS North Carolina Joins the Fleet" (Press release). Wilmington, North Carolina: Fleet Public Affairs Center Atlantic. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Zeldis, Jennifer, LT (26 October 2008). "USS New Hampshire Joins Fleet" (Press release). Kittery, Maine: Fleet Public Affairs Center Atlantic. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ McKnight, Kleynia (27 March 2010). "Submarine New Mexico Joins the Fleet" (Press release). Norfolk, Virginia: Navy Public Affairs Support Element - East. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Merritt, T.H. (1 August 2010). "USS Missouri Joins Commissioned Fleet" (Press release). Groton, Connecticut: Submarine Group 2 Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "USS Missouri". United States Navy. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Durie, Eric, ENS (29 October 2011). "Navy's Newest Submarine, California Namesake Joins Fleet in Norfolk" (Press release). Norfolk, Virginia: Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Sims, Hayley, LT (4 June 2012). "USS Mississippi Commissioned in Namesake State" (Press release). Pascagoula, Mississippi: Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "Navy to Christen Submarine Minnesota" (Press release). Washington, DC: Department of Defense Public Affairs. 25 October 2012. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Lindberg, Joseph (24 October 2012). "Submarine USS Minnesota to be commissioned Saturday". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "USS NORTH DAKOTA (SSN 784)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "USS JOHN WARNER (SSN 785)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "ILLINOIS (SSN 786)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b LaGrone, Sam (29 August 2016). "Attack Boat Illinois Delivers Early to Navy". USNI News. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "WASHINGTON (SSN 787)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Stanford, Julianne (7 October 2017). "New USS Washington to be commissioned Saturday". Kitsap Sun. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "COLORADO (SSN 788)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Upcoming US Navy Ship Commissionings". navycommissionings.org. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "INDIANA (SSN 789)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Commissioning - USS Indiana (SSN 789) Commissioning Committee". ussindiana.org. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "SOUTH DAKOTA (SSN 790)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Events | USS SOUTH DAKOTA SSN 790". USS SOUTH DAKOTA (SSN 790). Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ "DELAWARE (SSN 791)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "US Navy has commissioned USS Delaware SSN 791 Virginia-class nuclear attack submarine". navyrecognition.com. 4 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "VERMONT (SSN 792)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Navy Secretary: Submarine to be named USS Vermont". WPTZ Burlington. Burlington, Vermont. Associated Press. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "SECNAV Names Virginia-class Submarine, USS Vermont" (Press release). Burlington, Vermont: Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus. 18 September 2014.

- ^ "The latest keel laying marks attack submarine construction". usnews.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "OREGON (SSN 793)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus Names Virginia-Class Submarine USS Oregon" (Press release). Portland, Oregon: Secretary of the Navy Public Affairs. 10 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Industries, Huntington Ingalls. "Photo Release--Huntington Ingalls Industries Authenticates Keel of Submarine Montana (SSN 794)". Huntington Ingalls Newsroom. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Newport News Shipbuilding Launches Submarine Montana". military.com.

- ^ "MONTANA (SSN 794)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Navy Christens future USS Hyman G. Rickover". United States Navy. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Navy Christens future USS Hyman G. Rickover". United States Navy. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "HYMAN G. RICKOVER (SSN 795)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ LaGrone, Sam (9 January 2015). "Navy Names Attack Boat After Rickover". USNI News. U.S. Naval Institute. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Mabus, Ray, Secretary of the Navy (January 2015). 60th Anniversary of "Underway on Nuclear Power" Ceremony and Naming Ceremony for USS Hyman G. Rickover (SSN 795) (PDF) (Speech). Washington Navy Yard, Washington, DC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "NEW JERSEY (SSN 796)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "Secretary of the Navy Names Virginia-Class Submarine USS New Jersey" (Press release). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs). 26 May 2015. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016..

- ^ "IOWA (SSN 797)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Industries, Huntington Ingalls. "Photo Release — Huntington Ingalls Industries Authenticates Keel of Virginia-Class Attack Submarine Massachusetts (SSN 798)". Huntington Ingalls Newsroom. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "MASSACHUSETTS (SSN 798)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "IDAHO (SSN 799)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "ARKANSAS (SSN 800)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "UTAH (SSN 801)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "OKLAHOMA (SSN 802)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "ARIZONA (SSN 803)". Naval Vessel Register. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ https://news.usni.org/2020/10/13/secnav-names-attack-boat-after-wwii-uss-barb-ddg-for-former-secnav-lehman

- ^ "Secretary of the Navy Kenneth J. Braithwaite - Growing the Fleet".

- ^ "US Navy 21st Century - SSN Virginia Class". Jeffhead.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "Submarine Industrial Base Council". Submarinesuppliers.org. 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "Naval Submarine League". Navalsubleague.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "Funding For U.S. Navy Subs Runs Deep". Aviation Week. 10 April 2013. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (22 October 2013). "Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ McCullough III, Bernard, VAdm (ret) (January 2013). "Now Hear This - The Right Destroyer at the Right Time". Proceedings. U.S. Naval Institute. 139 (1/1, 319). Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ Pike, John. "SSN-774 Virginia-class NSSN New Attack Submarine". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Eckstein, Megan. "Navy New Virginia Block VI Virginia Attack Boat Will Inform SSN(X)". news.usni.org. USNI. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Future Attack Submarine". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2011 Shipbuilding Plan (PDF) (Report). Congressional Budget Office. May 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (23 October 2014). "Navy Starting Work on New SSN(X) Nuclear Attack Submarine". USNI News. U.S. Naval Institute. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ PEO Subs: Navy's Future Attack Sub Will Need Stealthy Advanced Propulsion, Controls for Multiple UUVs Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine - News.USNI.org, 9 March 2016

- ^ US Navy's Next Submarine: Super Stealthy and Now Underwater Aircraft Carrier? Archived 16 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine - Nationalinterest.org, 14 July 2016

- ^ "'This will be a staged farce': Chinese embassy unhappy with Australia-US joint statement". www.abc.net.au. 17 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ GDC (17 September 2021). "Australia To Build Eight Nuclear Submarines Based On Virginia-class Block V". Global Defense Corp. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Australia to acquire nuclear subs in historic AUKUS deal". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Submarines | Submarines | ASC". www.asc.com.au. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ GDC (16 September 2021). "Australia To Acquire Nuclear-powered Submarine, Scraps Conventional Submarine Project". Global Defense Corp. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Australia nuclear submarine deal: Aukus defence pact with US and UK means $90bn contract with France will be scrapped". theguardian.com. 15 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

Further reading[]

- Clancy, Tom (2002). Submarine: A Guided Tour Inside A Nuclear Warship. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-18300-7. OCLC 48749330.

- Christley, J. L. (2000). United States Naval Submarine Force Information Book. Marblehead, Massachusetts: Graphic Enterprises of Marblehead. OCLC 53364278.

- Christley, Jim (2007). US Nuclear Submarines: The Fast Attack. Oxford, UK. ISBN 978-1-84603-168-7. OCLC 141383046.

- Cross, Wilbur; Feise, George W. (2003). Encyclopedia of American Submarines. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4460-3. OCLC 48131805.

- Gresham, John; Westwell, Ian (2004). Seapower. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books. ISBN 978-0-7858-1792-5. OCLC 56578494.

- Holian, Thomas (Winter 2007). "Voices from Virginia: Early Impressions from a First-in-Class". Undersea Warfare. 9 (2). Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Johnson, Dave, CAPT; Muniz, Dustin, LTJG (Winter 2007). "More for Less: The Navy's Plan to Reduce Costs on Virginia-class Submarines While Increasing Production". Undersea Warfare. 9 (2). Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Little, Molly (Summer 2008). "The Elements of Virginia". Undersea Warfare Magazine (38). Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009. Updates on the boats of the Virginia-class

- Little, Molly (Summer 2008). "A Snapshot of the Virginia-class With Rear Adm. (sel.) Dave Johnson". Undersea Warfare (38). Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009. Q&A on the Virginia-class program since the Winter 2007 article

- Parker, John (2007). The World Encyclopedia of Submarines. London: Lorenz. ISBN 978-0-7548-1707-9. OCLC 75713655.

- Polmar, Norman (2001). The Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-656-6. OCLC 47105698.

- The Virginia Class Submarine Program (Report). Fort Belvoir, Virginia: Defense Standardization Program Office. 2007. OCLC 427536804.

| Library resources about Virginia-class submarine |

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Virginia class submarines. |

- Naval History & Heritage Command

- VIRGINIA CLASS ATTACK SUBMARINE - SSN

- Stealth, Endurance, and Agility Under the Sea

- Virginia Class Submarines Some U.S. Navy Photos of Virginia-class submarines

- Submarine Industrial Base Resources Information about the Submarine Industrial Base

- Submarine classes

- Naval ships of the United States

- Virginia-class submarines

- Submarines of the United States Navy

- Submarines of the United States