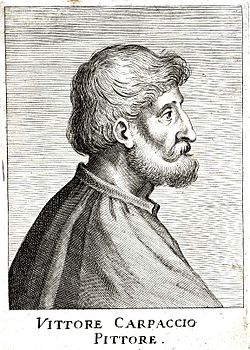

Vittore Carpaccio

Vittore Carpaccio | |

|---|---|

Vittore Carpaccio | |

| Born | c. 1465 |

| Died | 1525/1526 (aged around 60) Venice, Venetian Republic |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting |

Vittore Carpaccio (UK: /kɑːrˈpætʃ(i)oʊ/, US: /-ˈpɑːtʃ-/, Italian: [vitˈtoːre karˈpattʃo]; c. 1465 – 1525/1526) was an Italian painter of the Venetian school, who studied under Gentile Bellini. He is best known for a cycle of nine paintings, The Legend of Saint Ursula. His style was somewhat conservative, showing little influence from the Humanist trends that transformed Italian Renaissance painting during his lifetime. He was influenced by the style of Antonello da Messina and Early Netherlandish art. For this reason, and also because so much of his best work remains in Venice, his art has been rather neglected by comparison with other Venetian contemporaries, such as Giovanni Bellini or Giorgione.

Biography[]

Carpaccio was born in Venice, the son of Piero Scarpazza, a leather merchant. Carpaccio, or Scarpazza, as the name was originally rendered, came from a family originally from Mazzorbo, an island in the diocese of Torcello. Documents trace the family back to at least the 13th century, and its members were diffused and established throughout Venice. His date of birth is uncertain: his principal works were executed between 1490 and 1519, ranking him among the early masters of the Venetian Renaissance, and he is first mentioned in 1472 in a will of his uncle Fra Ilario.[1] Upon entering the Humanist circles of Venice, he changed his name to Carpaccio, an italianized form of Scarpanza. After signing an early work "Vetor Scarpanzo," he used variants of the Latin "Carpatio" or "Carpathius" for the rest of his career.[2] He was a pupil (not, as sometimes thought, the master) of Lazzaro Bastiani, who, like the Bellini and Vivarini, was the head of a large atelier in Venice.[1]

Work[]

Carpaccio's earliest known solo works are a Salvator Mundi in the Collezione Contini Bonacossi and a Pietà now in the Palazzo Pitti. These works clearly show the influence of Antonello da Messina and Giovanni Bellini – especially in the use of light and colors – as well as the influence of the schools of Ferrara and Forlì.

In 1490 Carpaccio began the famous Legend of St. Ursula, for the Venetian Scuola dedicated to that saint. The subject of the works, which are now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, was drawn from the Golden Legend of Jacopo da Varagine. In 1491 he completed the Glory of St. Ursula altarpiece. Indeed, many of Carpaccio's major works were of this type: large scale detachable wall-paintings for the halls of Venetian scuole, which were charitable and social confraternities. Three years later he took part in the decoration of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, painting the Miracle of the Relic of the Cross at the Ponte di Rialto.

In the opening decade of the sixteenth century, Carpaccio embarked on the works that have since awarded him the distinction as the foremost orientalist painter of his age.[3] From 1502 to 1507 Carpaccio executed another notable series of panels for the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni which served one of Venice's immigrant communities (Schiavoni meaning "Slavs" in Venetian dialect). Unlike the slightly old-fashioned use of a continuous narrative sequence found in the St. Ursula series, wherein the main characters appear multiple times within each canvas, each work in the Schiavoni series concentrates on a single episode in the lives of the Dalmatian's three patron Saints: St. Jerome, St. George and St. Trifon. These works are thought of as "orientalist" because they offer evidence of a new fascination with the Levant: a distinctly middle-eastern looking landscape takes an increasing role in the images as the backdrop to the religious scenes. Moreover, several of the scenes deal directly with cross-cultural issues, such as translation and conversion.

For example, St. Jerome, translated the Greek Bible to Latin (known as the Vulgate) in the fourth century. Then the St. George story addressed the theme of conversion and the supremacy of Christianity.

According to the Golden Legend, George, a Christian knight, rescues a Libyan princess who has been offered in sacrifice to a dragon. Horrified that her pagan family would do such a thing, George brings the dragon back to her town and compels them into being baptized.[4] The St. George tale was enormously popular during the renaissance, and the confrontation between the knight and the dragon was painted by numerous artists. Carpaccio's depiction of the event thus has a long history; less common is his rendition of the baptism moment. Although unusual in the history of St. George pictures, St. George Baptizing the Selenites offers a good example of the type of oriental subjects were popular in Venice at the time: great care and attention is given the foreign costumes, and hats are especially significant in indicating the exotic. Note that in The Baptism one of the recent converts has ostentatiously placed his elaborate red-and-white, jewel-tipped turban on the ground in order to receive the sacrament.

Fortini Brown argues that this increased interest in exotic eastern subject matter is a result of worsening relations between Venice and the Ottoman Turks: "as it became more of a threat, it also became more of an obsession."[5] His relief of the façade of the former School of the Albanians in Venice reflects this interest, as it commemorates two sieges of Shkodra in 1474 and 1478, the latter of which Sultan Mehmed II directed personally.

At about the same time, from 1501–1507, he worked in the Doge's Palace, together with Giovanni Bellini, in decorating of the Hall of the Great Council. Like many other major works, the cycle was entirely lost in the disastrous fire of 1577.

Dating from 1504–1508 is the cycle of Life of the Virgin for Scuola degli Albanesi,[6] largely executed by assistants, and now divided between the Accademia Carrara of Bergamo, the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, and the Ca' d'Oro of Venice.

In later years Carpaccio appears to have been influenced by Cima da Conegliano, as evidenced in the Death of the Virgin from 1508, at Ferrara.[1] In 1510 Carpaccio executed the panels of Lamentation on the Dead Christ and The Meditation on the Passion, where the sense of bitter sorrow found in such works by Mantegna is backed by extensive use of allegoric symbolism. Of the same year is a Young Knight in a Landscape, now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection of Madrid.

In 1516, he painted a Sacra Conversatione painting in then Venetian town of Capodistria (now Koper in Slovenia), which is hanging in its Cathedral of the Assumption. Carpaccio created several more works in Capodistria, where he spent the last years of his life and also died.[7]

Between 1511 and 1520 he finished five panels on the Life of St. Stephen for the Scuola di Santo Stefano. Carpaccio's late works were mostly done in the Venetian mainland territories, and in collaboration with his sons Benedetto and Piero. One of his pupils was Marco Marziale.

Gallery[]

- Vittore Carpaccio

Holy Pilgrim and St. Sebastian National Museum of Serbia (1495)

Preparation of Christ's Tomb (1505), Staatliche Museen, Berlin

The Virgin Reading (between 1505 and 1510), National Gallery of Art, Washington

St. George Baptizing the Selenites (1507), Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice

Young Knight in a Landscape (1510), Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Madrid

Portrait of the Doge Leonardo Loredan (1510), Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti di Bergamo

Portrait of a Venetian Nobleman ' (c. 1510) Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena

San Vitale on horse (1514)

The Sermon of St. Stephen (1514), Louvre, Paris

St. Paul (1520), San Domenico, Chioggia

Sant' Orsola polyptych Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

Birth of the Virgin, Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti di Bergamo

Annunciation, Ca' d'Oro, Venice

Two Venetian ladies, Museo Correr, Venice

Hunting on the Lagoon, Getty Center, Los Angeles

Hunting on the Lagoon" & "Two Venetian Ladies" (reconstruction)

Saint John the Baptist, Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa

Main works[]

- Zara Polyptych (c. 1480–1490) – Museum of Sacred Art, Zadar Cathedral

- Portrait of Man with Red Beret (1490–1493) – Tempera on wood, 35 × 23 cm, Museo Correr, Venice

- The Legend of St. Ursula (1490–1496) a cycle of nine canvasses – Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Arrival of the Ambassadors

- The Departure of the Ambassadors

- The Return of the Ambassadors

- Meeting of Ursula and the Prince

- The Saint's Dream

- Meeting of the Pilgrims with the Pope

- Arrivals of the Pilgrims in Cologne

- The Martyrdom and the Funeral of St. Ursula

- Glory of St. Ursula

- Miracle of the Relic of the Cross at the Ponte di Rialto (The Healing of the Madman, c. 1496) – Tempera on canvas, 365 × 389 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Christ between Four Angels and the Instruments of the Passion (1496) – Oil on panel, 162 × 163 cm, Civic Museums, Udine

- (1500) – Tempera on wood, 73 × 111 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- (c. 1500) – Tempera on panel, Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona

- Cycle in San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice (1502–1507) – Nine tempera panels, Scuola San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice

- (1504–1508)

- Birth of the Virgin – Tempera on canvas, 126 × 128 cm, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

- The Marriage of the Virgin – Canvas, 130 × 140 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

- The Presentation of the Virgin – Canvas, 130 × 137 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

- Holy Family and donors (1505) – Tempera on canvas, 90 × 136 cm, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon

- Holy Conversation (c. 1505) – Tempera on canvas, 92 × 126 cm, Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon

- (1505–1510) – Tempera on canvas, 78 × 51 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Madonna and Blessing Child (1505–1510) – Tempera on canvas, 85 × 68 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- St. Thomas in Glory between St Mark and St Louis of Toulouse (1507) – Tempera on canvas, 264 × 171 cm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

- Two Venetian Ladies (c. 1510) – Oil on wood, 94 × 64 cm, Museo Correr, Venice

- (c. 1510) – Oil on canvas, 102 × 78 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- (1510) – Tempera on panel, 421 × 236 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

- Portrait of a Knight (1510) – Tempera on canvas, 218 × 152 cm, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Madrid

- Portrait of a Young Woman – Panel, 57 × 44 cm, Private collection

- (c. 1510) – Oil and tempera on wood, 70,5 × 86,7 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- St George and the Dragon (1516) – Oil on canvas, 180 × 226 cm, San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice

- The Lion of St Mark (1516) – Tempera on canvas, 130 × 368 cm, Doge's Palace, Venice

- The Dead Christ (c. 1520) – Tempera on canvas, 145 × 185 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- Stories from the Life of St. Stephen (1511–1520)

- St Stephen is Consecrated Deacon (1511) – Tempera on canvas, 148 × 231 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- The Sermon of St. Stephen (1514) – Tempera on canvas, 152 × 195 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Disputation of St. Stephen (1514) – Tempera on canvas, 147 × 172 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

- The Stoning of St Stephen (1520) – Tempera on canvas, 142 × 170 cm, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

- Virgin and Child With Saint John(1490) – Stadel Art Museum, Frankfurt

- Metamorphosis of Alcyone (c. 1502–1507) – Philadelphia Museum of Art

See also[]

Notes[]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

- ^ Jump up to: a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Carpaccio, Vittorio". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 382.

- ^ "Artist Info".

- ^ Fortini Brown, p. 69.

- ^ Jacobus de Voraigine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, tr. William Granger Ryan, Vol I (Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 240.

- ^ Fortnini Brown, p. 69.

- ^ Kathleen Kuiper (February 1, 2010), The 100 Most Influential Painters & Sculptors of the Renaissance (I ed.), Rosen Education Service, pp. 171–172, ISBN 978-1615300044

- ^ "Leto Vittoreja Carpaccia, spomin na čas, ko je Koper veljal za "istrske Atene"" [The Year of Vittore Carpaccio, the Memory of Time when Koper Was Considered the "Athens of Istria"] (in Slovenian). MMC RTV Slovenija. 5 February 2016.

References[]

- Patricia Fortini Brown, Venetian narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988/1994)

- Daniele Trucco, "Vittore Carpaccio e l’esasperazione dell’orrido nell’iconografia del Rinascimento", in «Letteratura & Arte», n. 12, 2014, pp. 9–23.

- Pompeo Molmenti, Gustav Ludwig, The Life and Works of Vittorio Carpaccio (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, W., 1907)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vittore Carpaccio. |

- vittorecarpaccio.org (150 works by Vittore Carpaccio)

- Paintings by Vittore Carpaccio

- Web Gallery of Art

- Carpaccio500. Koper Regional Museum.

- 1460s births

- 1520s deaths

- 15th-century Italian painters

- 16th-century Italian painters

- 15th-century Venetian people

- 16th-century Venetian people

- Italian male painters

- Italian Renaissance painters

- People from Koper

- Mannerist painters

- Orientalist painters

- Painters from Venice