Waitara, New Zealand

Waitara | |

|---|---|

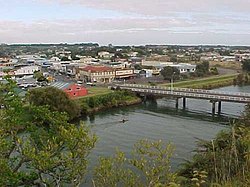

Waitara and the Waitara River | |

| |

| Coordinates: 38°59′45″S 174°13′59″E / 38.99583°S 174.23306°ECoordinates: 38°59′45″S 174°13′59″E / 38.99583°S 174.23306°E | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Taranaki |

| District | New Plymouth District |

| Ward | North |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.66 km2 (2.19 sq mi) |

| Population (June 2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 7,270 |

| • Density | 1,300/km2 (3,300/sq mi) |

| Postcode(s) | 4320 |

Waitara is a town in the northern part of the Taranaki region of the North Island of New Zealand. Waitara is located just off State Highway 3, 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) northeast of New Plymouth.

Waitara was the site of the outbreak of the Taranaki Wars in 1860 following the attempted purchase of land for British settlers from its Māori owners. Disputes over land that was subsequently confiscated by the Government continue to this day.

The commonly accepted meaning of the name Waitara is "mountain stream", though Maori legend also states that it was originally Whai-tara—"path of the dart". In 1867 the settlement was named Raleigh, after Sir Walter Raleigh. It reverted to its former name with the establishment of the borough of Waitara in 1904.

History and culture[]

Early history[]

Prior to European colonisation, Waitara lay on the main overland route between the Waikato and Taranaki districts. Vestiges of numerous pā on all strategic heights in the district indicate close settlement and closely contested possession, just before and in early European times, by various tribes.[3] Whalers and sealers, who had come from the northern hemisphere, gained help from and formed relationships with local Māori in the early 19th-century, but the area was largely vacated in the 1820s and 1830s following warfare between the resident Te Āti Awa iwi (tribe) and those of iwi from north Auckland down to the Waikato. Some Te Āti Awa were taken to Waikato as prisoners and slaves, but most migrated to the Cook Strait area in pursuit of guns and goods from whalers and traders.

Pākehā settlers who came to New Plymouth (founded in 1841) in the 1840s and 1850s viewed nearby Waitara as the most valuable of Taranaki's coastal lands because of its fertile soil and superior harbour. The New Zealand Company drew up plans for settlement from New Plymouth to beyond Waitara, and sold blocks to immigrants despite a lack of proof that the company's initial purchase of the land had been legitimate. The company claimed that Te Āti Awa had either abandoned the land or lost possession of it, owing to conquest by Waikato Māori.[4] (The later upheld this view, but subsequently Governor Robert FitzRoy (in office 1843–1845) rejected it, as did the Waitangi Tribunal in 1996.)

First Taranaki War[]

Tensions between settlers and local Māori began as early as July 1842, when settlers who had taken up land north of the Waitara River were driven from their farms. A year later 100 men, women and children sat in a surveyors' path to disrupt the surveying of land for sale.[4]

Between March and November 1848 Wiremu Kīngi, a Te Āti Awa chief who staunchly opposed the sale of land in the Waitara area, returned to the district from Waikanae with almost 600 men, women and children and some livestock to retake possession of the land. They established substantial cultivations of wheat, oats, maize and potatoes, selling it to settlers and also for export; his followers also laboured on settler farms.[4] The Waitangi Tribunal noted that the group allegedly eventually owned 150 horses and up to 300 head of cattle.

Despite Kingi's opposition however, payments were made by government agents secretly to Maori individuals for prospective sales of land in the Waitara area, prompting spates of violence between those supporting and opposing land sales.

In 1857 the issue came to a head with the offer for sale of land at Waitara and at Turangi, further to the north, by two individuals, Ihaia Te Kirikumara and a minor chief, Pokikake Te Teira.[4] Teira's 600-acre (240 hectare) Waitara block, located on the west side of the Waitara River and known as the Pekapeka block, became the focal point of a dispute between the colonial government (chiefly representing settlers) and Māori over the right of individuals to sell land that Māori custom regarded as owned by the community.[5] The dispute ultimately led to the outbreak of war in Waitara on 17 March 1860, when 500 troops began a bombardment of Kingi's Te Kohia pā, which had been built two days' prior.[4][6] By the end of March, of the four kāinga in the Pekapeka block (Te Whanga, Kuikui, Hurirapa and Wherohia), only Hurirapa, the community led by Ihaia and Teira, remained.[6] Imperial troops established Camp Waitara to the south of the Pekapeka block, at the former location of Pukekohe pā, which became the base of the 40th Regiment, and was one of the largest redoubts in the country.[6] The war, in which 2,300 Imperial troops fought about 1,400 Māori, ran for 12 months before a ceasefire was negotiated.[4]

Later campaigns during the war included the major British defeat in the Battle of Puketakauere, close to Te Kohia pā, on 27 June 1860 which cost the lives of 32 Imperial troops and of five Māori. A major British sapping operation at the strongly defended Te Arei pā up the Waitara River began in February 1861, but was abandoned when a ceasefire was effected the following month.[7] As a result of this operation, Colour Sergeant John Lucas was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Second Taranaki War[]

In May 1863 war resumed in Taranaki.[8][9] The government immediately renounced the earlier Waitara purchase, abandoning all claims to it, and instead created a plan for the confiscation of greater tracts of land under new laws, supposedly as a reprisal for the Oakura killings. In 1865 the Pekapeka block that had been at the heart of the initial dispute with Kingi was confiscated–therefore finding its way back into government control–on the basis that Kingi was at war, though the Waitangi Tribunal concluded there was no evidence he had engaged in hostilities after 1861.[10]

In 1884 the Government returned as "Native reserves" 103,000 hectares of the 526,000 hectares of Taranaki land it had confiscated, although the land remained in government control. By 1990 half of the "reserves" had been sold to Pākehā settlers by the Native Trustee without reference to Maori.[11] The remainder was leased to settlers with Maori receiving only a "peppercorn" rental return.

The Pekapeka Block–which had been the catalyst of the Taranaki Wars and, by extension, the policy of land confiscation–was divided up and given as endowments, or gifts, to the Waitara Borough Council and Taranaki Harbours Board. In 1989 the land was transferred to the New Plymouth District Council, which in turn voted in March 2004 to sell it to the Government with the intention of it being passed to Te Āti Awa as part of the Waitangi Treaty settlement.[12] That process was blocked by the High Court in November 2005 after a challenge by the Waitara Leaseholders Association. Association members, each of whom owns a house but leases the (once confiscated) land on which it stands, want to own the land freehold.[13][14]

Treaty settlement[]

In September 1990 the Waitangi Tribunal began hearing 21 Treaty of Waitangi claims concerning the Taranaki district. Much of the tribunal's investigation focused on events around Waitara from 1840 to 1859.

The tribunal presented its report to the Government in June 1996, noting: "The Taranaki claims could be the largest in the country. There may be no others where as many Treaty breaches had equivalent force and effect over a comparable time. For the Taranaki hapu, conflict and struggle have been present since the first European settlement in 1841 ... Taranaki Maori were dispossessed of their land, leadership, means of livelihood, personal freedom, and social structure and values. As Maori, they were denied their rights of autonomy, and as British subjects, their civil rights were removed. For decades, they were subjected to sustained attacks on their property and persons."

In its report, the tribunal observed that to the offence of local Maori, many street names in Waitara honoured the architects of the illegal land confiscation, including chief crown purchasing agent Donald McLean, Land Purchase Commissioner Robert Parris, Governor Thomas Gore Browne and military officers Charles Emilius Gold and Peter Cracroft. It said: "It is our view that name changes are needed. It is when leaders like Kingi, who understood the prerequisites for peace, are similarly memorialised on the land and embedded in public consciousness that those names will cease to stand for conquest and the Waitara war will end."

In November 1999 the New Zealand Government signed a Heads of Agreement with Te Āti Awa to settle its claims, a process that would provide financial compensation and an apology for the confiscation of land.[15]

Marae[]

Waitara has two marae.

Kairau Marae features Te Hungaririki meeting house, and is a meeting ground for the Pukerangiora hapū of Te Āti Awa.[16][17] In October 2020, the Government committed $300,080 from the Provincial Growth Fund to upgrade the marae, creating 15 jobs.[18]

Ōwae or Manukorihi Marae features Te Ikaroa a Māui meeting house and is a marae of Te Āti Awa hapū of Manukorihi, Ngāti Rāhiri and Ngāti Te Whiti.[16][17] In October 2020, the Government committed $360,002 to upgrade the marae and another marae, creating 15 jobs.[18]

Demographics[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 6,291 | — |

| 2013 | 6,483 | +0.43% |

| 2018 | 6,918 | +1.31% |

| Source: [19] | ||

Waitara, comprising the statistical areas of Waitara West and Waitara East which cover 3.39 km2 (1.31 sq mi) and 2.27 km2 (0.88 sq mi) respectively,[1] had a population of 6,918 at the 2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 435 people (6.7%) since the 2013 census, and an increase of 627 people (10.0%) since the 2006 census. There were 2,613 households. There were 3,369 males and 3,543 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.95 males per female, with 1,512 people (21.9%) aged under 15 years, 1,311 (19.0%) aged 15 to 29, 2,799 (40.5%) aged 30 to 64, and 1,296 (18.7%) aged 65 or older.

Ethnicities were 72.4% European/Pākehā, 43.1% Māori, 3.5% Pacific peoples, 1.5% Asian, and 1.6% other ethnicities (totals add to more than 100% since people could identify with multiple ethnicities).

The proportion of people born overseas was 6.3%, compared with 27.1% nationally.

Although some people objected to giving their religion, 54.9% had no religion, 30.4% were Christian, 0.2% were Hindu, 0.1% were Muslim, 0.2% were Buddhist and 3.3% had other religions.

Of those at least 15 years old, 342 (6.3%) people had a bachelor or higher degree, and 1,821 (33.7%) people had no formal qualifications. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 2,298 (42.5%) people were employed full-time, 657 (12.2%) were part-time, and 351 (6.5%) were unemployed.[19]

| Name | Population | Households | Median age | Median income |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waitara West | 4,011 | 1,536 | 38.6 years | $22,900[20] |

| Waitara East | 2,907 | 1,077 | 40.5 years | $24,500[21] |

| New Zealand | 37.4 years | $31,800 |

Economy[]

The first port in Taranaki to engage in international trade was Waitara, in 1823, when the barque William Stoveld anchored in the river mouth and traded with the Maori. With the establishment of the freezing works in 1872 the river port became even more important to the Province. However the river has a bar at its entrance which can only be crossed at high tide. With the development of a breakwater at the port in New Plymouth, and the railway to New Plymouth the Waitara port quickly became unimportant.

Construction of a railway line between Waitara and New Plymouth began in August 1873. By the time the line opened on 14 October 1875, the town had a harbour board, two printing houses, a soap and candle factory, an iron foundry, a boat-building yard, two breweries, a wool-scouring plant and a tannery.

From 1887 the economy of Waitara became dependent on the frozen meat trade–first to Great Britain and since the creation of the European Common Market, to Asian countries. Except for some very early shipments from Waitara, frozen meat was transported to the port of New Plymouth by rail.

In 1902 Thomas Borthwick and Sons (Australasia) Ltd, a subsidiary of a UK company, bought the Waitara Freezing and Cold Storage Company plant at Waitara. Until 1998, the freezing works employed between 1000 and 1500 workers, by far the largest employer in a town with a population of between 3000 and 5000. In 1990, Borthwicks sold the Waitara works to AFFCO Holdings.

In 1995 AFFCO closed the Waitara works with the consequent severe loss of employment in the town. The shutdown followed the closure of a Swanndri clothing factory, a small-scale but locally significant Subaru car assembly plant and a wool scouring plant. The number of registered unemployed in the town rose from 700 to 1000, helping to boost the unemployment rate for the Taranaki region, which includes New Plymouth and Waitara, to 9.8 percent, compared with the national average of 6.7 percent.

The loss of jobs affected Maori workers disproportionately because they were heavily represented in the work's labour force. Maori were 3.4 times more likely than non-Maori to be living in a "deprived" situation.[22]

After the closure, the majority of buildings making up the Waitara freezing works were demolished, significantly changing the townscape (the area on the right on the far side of the river in the image of Waitara below, was the site of the freezing works).

ANZCO Foods Group subsequently built a plant to manufacture smallgoods such as salami, sausages and hamburger patties on the site of the freezing works. However, AFFCO went to court to enforce a 20-year encumbrance which restricts meat processing and associated activities on the site. It succeeded in both the High Court and the Court of Appeal in preventing the new plant from opening, although an ANZCO subsidiary was allowed to continue using freezer and coolstore facilities there. The two companies are said to have reached an agreement. ANZCO now operates from the site, and has become one of the major employers in the township.

Although the freezing works had been the economic backbone of Waitara, for over 75 years the plants had discharged blood, waste and effluent from the slaughter houses, chains and tanneries directly into the Waitara River, less than 3 km from the sea, well within the tidal zone.

Even after an ocean outfall was built in collaboration with the town council's sewerage system, at Waitangi Tribunal hearings in Waitara, local Maori gave evidence that they had "…historic associations with the coastline in this area and depend upon the sea resources to provide them with the diet to which they have been accustomed for many centuries…..thus the contamination of one reef would deprive hapu which customarily was entitled to the sea food from the reef".

Two large petrochemical plants are now the most important industrial activity in Waitara. The Waitara Valley plant is dedicated to production of methanol from natural gas (about 1500 tonnes per day). The Motunui plant, originally designed to produce synthetic petrol from methanol was modified to produce chemical grade methanol for export.

The high cost of synthetic petrol production and low market prices made the process uneconomical at the time. Motunui has the two largest wooden structures in the southern hemisphere and they are only exceeded in size, anywhere in the world, by the Buddhist temple Tōdai-ji in Nara, Japan. The Motunui plant was closed in December 2004, and restarted in 2008. An onshore production facility for the Pohokura oilfield has been built immediately adjacent to it.

The town continues to be a service centre for the farming sector, particularly to the north and northeast.

Farming in the Waitara catchment includes dairying, beef cattle for meat, sheep for both meat and wool, fruit—mainly kiwifruit—other horticulture including tree and shrub nurseries, and poultry for meat and eggs.

Education[]

Waitara High School is the only secondary (years 9–13) school in Waitara with a roll of 389.[23] The school celebrated 60 years in 2007.[24]

Manukorihi Intermediate is an intermediate (years 7–8) school with a roll of 239.[25] It celebrated its 25th jubilee in 1999.[26]

Waitara Central School and Waitara East School are contributing primary (years 1–6) schools with rolls of 100[27] and 219,[28] respectively. Waitara Central celebrated its 125th jubilee in 2000.[29]

St Joseph's School is a full primary (years 1–8) school with a roll of 60.[30] It is a state integrated Catholic school.[31]

All these schools are coeducational. Rolls are as of March 2021.[32]

Sport[]

Cricket[]

The original Waitara Cricket Club was formed in October 1878, with Mr. J. Elliot elected club captain. Mr L. Issit as secretary and treasurer and a committee consisting of Messrs. Bayly, Tutty and Smith. Annual subscriptions for members were set at 10s. The club colours were chosen to be the same as the Waitara Boating Club, "scarlet and white".[33]

Soccer[]

The first association football club at Waitara formed in 1905.[34] The first match the club played was against New Plymouth AFC at the Camp Reserve in Waitara on the afternoon of Thursday, 18 May. Waitara took the lead early in the match, then New Plymouth scored three answered goals for a 3–1 victory.[35] In its first season in the Taranaki Championship, the club won the Julian Cup [36][37]

In popular culture[]

In 2020, Waitara was featured in a reality documentary-series Taranaki Hard.[38]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "ArcGIS Web Application". statsnz.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "Population estimate tables - NZ.Stat". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 1966

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I: 1845–1864, Chapter 17. 1922.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Prickett, Nigel (1994). "PAKEHA AND MAORI FORTIFICATIONS OF THE FIRST TARANAKI WAR, 1860-61". Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum. 31: 1–87. ISSN 0067-0464.

- ^ Cowan, James (1922). The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, Vol. 1, chapter 20, 1845–1864.

- ^ Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1st ed.). Auckland: Penguin. p. 119. ISBN 0-14-011162-X.

- ^ James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Vol I, Chapter 25, 1922

- ^ The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal, page 90

- ^ Puke Ariki website Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Press release from Hon. Margaret Wilson Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Waitara leaseholders plan court action on Treaty land". The New Zealand Herald. NZPA. 10 February 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ Puke Ariki information sheet on Waitara leasehold issue Archived 15 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Govt.nz Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Te Kāhui Māngai directory". tkm.govt.nz. Te Puni Kōkiri.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Māori Maps". maorimaps.com. Te Potiki National Trust.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Marae Announcements" (Excel). growregions.govt.nz. Provincial Growth Fund. 9 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Waitara West (218500) and Waitara East (218900).

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Waitara West

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Waitara East

- ^ Treasury Working Paper 01/17, Geography and the Inclusive Economy, p 10.

- ^ Education Counts: Waitara High School

- ^ "Jubilees & reunions: Waitara High School" (– Scholar search), Education Gazette New Zealand, 86 (10), 18 June 2007[dead link]

- ^ Education Counts: Manukorihi Intermediate

- ^ "Jubilees & reunions: Manukorihi Intermediate School" (– Scholar search), Education Gazette New Zealand, 77 (12), 20 July 1998[dead link]

- ^ Education Counts: Waitara Central School

- ^ Education Counts: Waitara East School

- ^ "Jubilees & reunions: Waitara Central School" (– Scholar search), Education Gazette New Zealand, 79 (3), 21 February 2000[dead link]

- ^ Education Counts: St Joseph's School, Waitara

- ^ "Education Review Report: St Joseph's School, Waitara". Education Review Office. 27 September 2017.

- ^ "New Zealand Schools Directory". New Zealand Ministry of Education. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ Taranaki Herald 1 November 1878 pg. 2 "Waitara Cricket Club"

- ^ "Association". Papers Past. 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Association Game - New Plymouth V Waitara". Papers Past. 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Waitara News". Papers Past. 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Football". Papers Past. 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Taranaki Hard". Television Three. Season 1 Episode 4. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

Further reading[]

- Michael King The Penguin History of New Zealand, 2003. Pp 205 & 212 ISBN 0-14-301867-1

- James Belich The New Zealand Wars, 1986. ISBN 0-14-011162-X

General historical works[]

- 1875–1950 Waitara school 75th jubilee: history of school and district, n.p.: n.p., c. 1950

- Waitara: 50th anniversary of borough, 1904–1954, New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Taranaki Daily News, 1954

- The wonder book of Taranaki: containing photographic reproductions of a selection of Taranaki’s scenic beauties; illustrations and descriptions of the principal towns, New Plymouth, Hawera, Stratford, Eltham, Inglewood, Waitara, Patea, and Opunkae; descriptive articles on Taranaki’s splendid motor highways, overseas shipping facilities of the province, features of the dairy industry, fertilizer works in Taranaki, educational advantages, hydro-electric power, forestry enterprise, etc., etc., New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Thos. Avery & Sons, 1927

- Alexander, Ada C. (1979), Waitara: a record, past and present, Waitara, [N.Z.] ; New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Waitara Borough Council ; Taranaki Newspapers

- Fraser, D. P.; Pigott, S. (1989), A town called Waitara: once known as Raleigh, Waitara, [N.Z.]: D. P. Fraser & S. Pigott

- Fraser, D. P. (1989), Waitara, Waitara, [N.Z.]: D. P. Fraser

- Johnston, Betti M. (1947), Waitara and its tributary region the study of a town-country community in North Taranaki [M.A.(Hons.) – Canterbury University College]

- Wright, Shona (1989), Clifton: a centennial history of Clifton County, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Clifton County Council, ISBN 0-473-00617-0

Business[]

- Methanol from Taranaki, New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Taranaki Newspapers, 1984

- The Petralgas Chemical Methanol plant, New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Petralgas Chemicals NZ Ltd., 1985

- Marshall, Jonathan KP (1991), Business 229 Financial Services, Personal Financial Services Group, National Office, [N.Z.]

- Berthold, Martin (c. 1999), Appendix one, fleet list: Bayly, Ogle & Co., Waitara: Mokau Steamship Co.: A.W. Ogle, manager, Sanson, [N.Z.]: M. Berthold, ISBN 0-473-05891-X

- de Jardine, Margaret (1992), The little ports of Taranaki: being Awakino, Mokau, Tongaporutu, Urenui, Waitara, Opunake, Patea, together with some historical background to each, New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: M. de Jardine, ISBN 0-473-01455-6

- Murphy, Peter T. (1976), BNZ Waitara, a century of service 1876–1976, Wellington, [N.Z.]: BNZ Archives

Churches[]

Anglican[]

- Alexander, Ada C. (1976), St John the Baptist, Waitara: centenary, 1876–1976, New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Taranaki Newspapers

Catholic[]

- Bradford, Patrick V. (1975), St. Joseph's Parish, Waitara: a history of the Catholic faith: 25th jubilee, 1975, Waitara, [N.Z.]: St. Joseph's Parish

Crossroads Church (Non-Denominational)[]

- Marshall, Jonathan KP (2004), Crossroads Church, Waitara, [N.Z.]: The Church

Methodist[]

- Musker, David; Whittaker, Rosemary (comps.) (2000), Waitara Methodist Church, 125th jubilee, 1875–2000, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Villa Photographic, ISBN 0-473-07686-1

- Surrey, Allan K. (1977), A centennial survey of the Waitara Methodist Church, 1875–1975, Waitara, [N.Z.]: A. Surrey

Presbyterian[]

- Hodge, L. D. (1989), Knox Presbyterian Church Waitara, Waitara, [N.Z.]: The Church

Clubs and organisations[]

- Clifton Park Bowling Club: 50th jubilee commemorative history, 1938–1988, Waitara, [N.Z.]: The Club, 1988

- Rotary Club of Waitara: district 994 – New Zealand: club history 1957–1982, New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Dorset Print, 1982

- Crow, Pauline M.; Crow, Dennis G. (1985), Waitara Volunteer Fire Brigade 75th jubilee, 1910–1985, Waitara, [N.Z.]: The Brigade

- Summers, Charles (1980), Clifton Rugby Club centennial 1880–1980, Waitara, [N.Z.] ; New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Clifton Rugby Football Club, 1980 ; Taranaki Newspapers

- Thrush, Grace (1988), Clifton Rowing Club: a centennial history 1888–1988, Waitara, [N.Z.]: The Club

Maori[]

- Report findings and recommendations of the Waitangi Tribunal on an application by Aila Taylor for and on behalf of Te Atiawa Tribe in relation to fishing grounds in the Waitara district, Wellington, [N.Z.]: The Tribunal, 1983

- Duff, Roger S. (1961), The Waitara swamp search [Records of the Canterbury Museum vol. VII, no. IV], Christchurch, [N.Z.]: Canterbury Museum

- Minchin, Geoff (1967), "The art of the carver", Taranaki Herald, New Plymouth, [N.Z.]

- Smith, Lee (1983), The Maori language in Waitara / Purongorongo whakamohio ma nga kaiuru ki te toronga tuatahi, 1973–1978 [Information bulletin (Survey of Language Use in Maori Households and Communities) ; 75], Wellington, [N.Z.]: New Zealand Council for Educational Research

People[]

- Genealogies and collected histories: collection of the late Clifford Arnold Perrett, 3 Aug 1931 – 28 Oct 2003, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Waitara History Project Group, 2004

- Hunt, Raymond M. (c. 1997), Hunt family tree: Charles, Sarah, 1853, 15th May, "Alma", 1857, Waitara, [N.Z.]: R.M. Hunt

- Hunt, Raymond M. (2002), A family tree Hunt, Waitara, [N.Z.]: R.M. Hunt, ISBN 0-473-09332-4

- Potroz, Erin (1999), Dr Edward Jonathon Goode, 1848–1936, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Erin Potroz

- Waite, Andrea; Sarten, Carolyn (c. 2000), Tom & Betsy Longstaff and descendants, 1827–1990, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Longstaff Family Reunion Committee

Schools[]

- 1875–1950 Waitara school 75th jubilee: history of school and district, n.p.: n.p., c. 1950

- Twenty-fifth jubilee of Waitara High School, 1947–1972, Waitara, [N.Z.] ; New Plymouth, [N.Z.]: Waitara High School Jubilee Committee ; Taranaki Newspapers, 1972

- Waitara Central School centenary, 1875–1975: souvenir booklet, 16th, 17th, 18th, May 1975, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Jubilee Committee, 1975

- Waitara High School jubilee, 1947–1997, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Waitara High School Jubilee Committee, 1997, ISBN 0-473-05019-6

- Wellington, Judi-Lee; Wellington, Marion E. (eds.) (2000), Waitara West School, Waitara Public, Waitara Primary, Waitara District High School, Waitara Central 125th Jubilee, 1875–2000, Waitara, [N.Z.]: Waitara Central SchoolCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Young, Valerie J.(ed.) (1988), 75th jubilee magazine: Waitara St. Patrick’s – St. Joseph’s School, 1912–1987, Waitara, [N.Z.]: St. Patrick's – St. Joseph's Jubilee CommitteeCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Waitara, New Zealand. |

- Conflict in the beginning

- 65th (2nd Yorkshire North Riding) Regiment of Foot

- Waitara High School website

- "Deed of Waitara. Of February 1860" – "Colonist", 1 September 1863.

- Populated places in Taranaki

- New Plymouth District