Wales in the Late Middle Ages

| History of Wales |

|---|

|

|

|

Wales in the Late Middle Ages spanned the years 1250-1500,[1] those years covered the period involving the closure of Welsh medieval royal houses during the late 13th century, and Wales' final ruler of the House of Aberffraw, the Welsh Prince Llywelyn II,[2] also the era of the House of Plantagenet from England, specifically the male line descendants of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou as an ancestor of one of the Angevin kings of England who would go on to form the House of Tudor from England and Wales.[3]

The House of Tudor would go on to create new borders by incorporating Wales into the Kingdom of England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542, effectively ever since then new shires had been created in place of castles, by changing the geographical borders of the Kingdoms of Wales to create a new definitions for towns and their surrounding lands.[4] The term Middle age is a Latin term coined in the 15th century for "Middle season" (Latin: media tempestas),[5] historians referring to the end of the late Middle Ages in Britain often reference the Battle of Bosworth Field involving Henry VII of England, which was the end the middle ages, and beginning of a new era in Wales.[6]

End of the Aberffraw era[]

The senior family of the Kingdom of Gwynedd would descend from Owain Gwynedd and within a century the House of Aberffraw would come to acquire the title Prince of Aberfraw, Lord of Snowdon and would have 'de faco' suzerainty over the Lords in Wales. The titular Princes did so in the battle, and after the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn II), his brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd (Dafydd III / David) carried on resistance against the English for a few months, but was never able to control any large area. He was captured and executed by hanging, drawing and quartering at Shrewsbury in 1283. King Edward I of England now had complete control of Wales. The Statute of Rhuddlan was issued from Rhuddlan Castle in north Wales in 1284. The Statute divided parts of Wales into the counties of Anglesey, Merioneth and Caernarvon, created out of the remnants of Llewelyn's Gwynedd. It introduced the English common law system, and abolished Welsh law for criminal cases, though it remained in use for civil cases. It allowed the King of England to appoint royal officials such as sheriffs, coroners, and bailiffs to collect taxes and administer justice. In addition, the offices of justice and chamberlain were created to assist the sheriff. The Marcher Lords retained most of their independence, as they had prior to the conquest. Most of the Marcher Lords were by now Cambro Norman i.e. Norman Welsh through intermarriage.[2][7]

Castles and Towns[]

After the Norman invasion of Wales, successive phases of castle construction in the British isles begun in the 11th century, then the 12th, but only in the 13th century did the Edwardian castle period begin in Wales. Dafydd III of Wales broke the Treaty of Aberconwy in place since 1277 to keep peace, and the manhunt begun the North Wales castle building phase with Conwy Castle, then Harlech and Caernarfon castles.[8][9] It was the likes of James of Saint George who hailed from Savoy, and brought European designed castles, St. George's official title was Master of the Royal Works in Wales (Latin: Magistro Jacobo de sancto Georgio, Magistro operacionum Regis in Wallia), and would work in Wales in Britain.[10] These Edwardian castles would either be burnt to the in the Glyndŵr Rising in the 15th century, and if they survived the Welsh rebellion they were later slighted, and then bulldozed by cannonballs in the English Civil War, in the 17th century, this was to prevent further military use e.g. Harlech castle was besieged successfully, but some still stand today as a testament to their construction. Caernarfon and Conwy castles have been incorporated into respective towns as examples of surviving castles.[11][12][13][14]

Edwardian castle era[]

King Edward I of England built a ring of impressive stone castles to consolidate his domination of Wales, and crowned his conquest by giving the title Prince of Wales to his son and heir in 1301.[15][16] Wales became, effectively, part of England, even though its people spoke a different language and had a different culture. English kings paid lip service to their responsibilities by appointing a Council of Wales, sometimes presided over by the heir to the throne. This Council normally sat in Ludlow, now in England but at that time still part of the disputed border area of the Welsh Marches.[citation needed] Welsh literature, particularly poetry, continued to flourish however, with the lesser nobility now taking over from the princes as the patrons of the poets and bards. Dafydd ap Gwilym who flourished in the middle of the fourteenth century is considered by many to be the greatest of the Welsh poets.[17]

Rhuddlan Castle built by master Mason St. George between 1280 and 1282 would be the name stakes for a new treaty which would incorporate all of Wales into one Principality in the Statute of Rhuddlan. The Treaty coincided with one of the last attacks of the Welsh on a Norman English built castle, Llywelyn II unsuccessfully attempting a revolt in 1282. The new government would include the ruling families of "Clares (Gloucester and Glamorgan), the Mortimers (Wigmore and Chirk), Lacy (Denbigh), Warenne (Bromfield and Yale), FitzAlan (Oswestry), Bohun (Brecon), Braose (Gower), and Valence (Pembroke)".[2][18] These families evolved from Welsh Marcher (Latin: Marchia Wallie) Lords who settled the borders, and settled the new Principality at the behest of King of England, whose families now descended from the Norman conquest who had by then integrated locally slower than their English compatriots.[19][20]

Castles were governed by Constables (Latin: ex officio), these men would be present like modern day police in each castle which was the centre of their respective towns. The constable lists of castles would vary but mostly were manned up until at least the Glyndwr rebellion, or thereabouts for over 150 years in the example of Flint Castle.[21][22] Flint castle in particular has held out over the ages in terms of its fame and notoriety, with thanks to William Shakespeare who wrote Richard II (play) and detailed the life and imprisonment of Richard II of England in the castle.[23] While Flint castle was slighted in the 17th century, the castle in the town of Conwy has enjoyed a relative longevity as a town centre, with 43 constables between 1284 – 1848. Flint along with most Welsh and English Edwardian castles were slighted or demolished eventually by the English civil war in the 17th century.[13][24]

Welsh and castles[]

Many castles in Wales are ruins today, an example is Criccieth Castle, built by Llywelyn the Great, the castle was garrisoned by an English army until the Owain Glyndwr rebelled in 1404, the town became occupied again by Welsh after the Glyndwr Rising.[25] Another example of a castle built by the Welsh people is Powis Castle, the once residence is a rare instance of a complete castle still in use today. It was built by Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, who was a member of the Royal Kingdom of Powys and ordered its construction in the 13th century, the castle and lands were leased by the Herbert family during 1578, but have since become the property of the Welsh National trust as of 1952 and is the former seat of George Herbert, 4th Earl of Powis.[26] Chirk Castle being another example of a Welsh fortress which has stood the test of time and is also under the protection of the national Trust.[27]

With Wales being cluttered with castles, it was during this Edwardian phase the most of the castles were erected after the Norman conquest.[28] However, during the Principality, very few castles were built, Raglan Castle being a 15th-century example was built by Sir William ap Thomas, the ‘blue knight of Gwent' a Welshman who started a new dynasty via his son William Herbert, 1st Earl who became owner a Welsh owner Raglan castle, as well as Raglan, the Hertbet's gained Chepstow from the English Earl of Norfolk, and then Raglan in 1508 passed to another English gentry family, by Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester who would be the first to use the estate as a private residence, this marked a new era in Welsh castles ownership and the usage of a public place in private hands.[29][30][31] As well as Raglan becoming owned by Welsh gentry, Carew Castle was gained by Rhys ap Thomas who mortgaged the estate and also too used the castle as a private residence.[32]

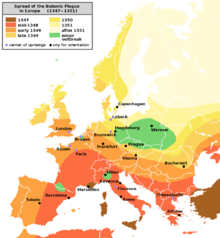

The Black Death[]

The Black Death arrived in Wales in late 1348. What records survive indicate that about 30% of the population died, in line with the average mortality through most of Europe.[citation needed]

Rebellions[]

There were a number of rebellions including ones led by Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294-5,[33] and by Llywelyn Bren, Lord of Senghenydd, in 1316–18. In the 1370s the last representative in the male line of the ruling house of Gwynedd, Owain Lawgoch, twice planned an invasion of Wales with French support. The English government responded to the threat by sending an agent to assassinate Owain in Poitou in 1378.[34]

Glyndŵr's rebellion[]

In 1400, a Welsh nobleman, Owain Glyndŵr, revolted against King Henry IV of England. Owain inflicted a number of defeats on the English forces and for a few years controlled most of Wales. Some of his achievements included holding the first Welsh Parliament at Machynlleth and plans for two universities. Eventually the king's forces were able to regain control of Wales and the rebellion died out, but Owain himself was never captured, betrayed nor tempted by Royal pardons. His rebellion caused a great upsurge in Welsh identity and he was widely supported by Welsh people throughout the country.[35][36]

As a response to Glyndŵr's rebellion, the English parliament passed the Penal Laws in 1402. These prohibited the Welsh from carrying arms, from holding office and from dwelling in fortified towns. These prohibitions also applied to Englishmen who married Welsh women. These laws remained in force after the rebellion, although in practice they were gradually relaxed.[37]

Wars of the Roses[]

In the Wars of the Roses over the English throne, which began in 1455, both sides made considerable use of Welsh troops. The main figures in Wales were the two Earls of Pembroke, the Yorkist Earl William Herbert and the Lancastrian Jasper Tudor. In 1485 Jasper's nephew, Henry Tudor, landed in Wales with a small force to launch his bid for the throne of England. Henry was of Welsh descent, counting princes such as Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys) among his ancestors, and his cause gained much support in Wales. Henry defeated King Richard III of England at the Battle of Bosworth with an army containing many Welsh soldiers and gained the throne as King Henry VII of England.[38]

Annexation to England[]

Under Henry VII's son, Henry VIII of England, the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542 were passed, annexing Wales to England in legal terms, abolishing the Welsh legal system, and banning the Welsh language from any official role or status, but it did for the first time define the Wales-England border and allowed members representing constituencies in Wales to be elected to the English Parliament.[39] They also abolished any legal distinction between the Welsh and the English, thereby effectively ending the Penal Code although this was not formally repealed.[40] With this new introduction came a new age where castles were being used as gentry homes by English Lords, and less as focal towns centres for the Welsh, Chepstow Castle being the example, whereas it was turned into the county of Monmouthshire.[4] The Principality of Wales came to an end as a legally defined territory with the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542.

References[]

- ^ Wallace K. Ferguson (1962). Europe in transition, 1300-1520. archive.org.

- ^ a b c Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 34. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 20, 13–21.

- ^ Wagner 2001, p. 206.

- ^ a b Turner, Rick; Johnson, Andy (2006). Chepstow Castle – its history and buildings. ISBN 1-904396-52-6.

- ^ Miglio, Massimo (2006). "Curial Humanism seen through the Prism of the Papal Library". In Mazzocco, Angelo (ed.). Interpretations of Renaissance Humanism. Brill's Studies in Intellectual History. Leiden: Brill. p. 112. ISBN 978-90-04-15244-1.

- ^ Saul, Nigel. Companion to Medieval England 1066–1485. ISBN 0752429698.

- ^ "LLYWELYN ap GRUFFYDD ('Llywelyn the Last,' or Llywelyn II), Prince of Wales (died 1282)". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ^ Taylor 1997, p. 9.

- ^ Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1888). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 14. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 204.

- ^ Morris, John E. (1901). The Welsh Wars of Edward I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 145.

- ^ Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1890). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 21. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 427–434.

- ^ Taylor 1997, pp. 10, 13, 19.

- ^ a b (Ashbee 2007, p. 16)

- ^ Tours in Wales, p. 125–, at Google Books

- ^ Davies 1987, p. 386.

- ^ Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1889). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 17. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 14–38.

- ^ "DAFYDD ap GWILYM (fl. 1340-1370), poet". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ^ Edwards, Owen Morgan (1885–1900). "Chapter 12". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 58-59.

- ^ Davies 2000, p. 271-288.

- ^ Freeman, Edward Augustus (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 751–756, see page 755.

- ^ Rickard, John. The Castle Community: The Personnel of English and Welsh Castles, 1272-1422. p. 198. ISBN 0851159133.

- ^ "Owain Glyndwr (c.1354-1416)". snowdonia.gov.wales.

- ^ Kantorowicz, H. Ernst (1957). The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 24–31.

- ^ The Heart of Northern Wales, p. 187-328, at Google Books

- ^ "Criccieth Castle". cadw.gov.wales.

- ^ "Powis Castle and Garden". nationaltrust.org.uk.

- ^ "Chirk castle". nationaltrust.org.uk.

- ^ "Is Wales the castle capital of the world?". cadw.gov.wales.

- ^ Johnson, Andy; Turner, Rick (2006). Chepstow Castle – its history and buildings. ISBN 1-904396-52-6.

- ^ "Raglan Castle". cadw.gov.wales.

- ^ Griffiths, R.A. (2004). "Herbert, William, first earl of Pembroke (c. 1423–1469)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13053. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "RHYS ap THOMAS, Sir (1449 - 1525), the chief Welsh supporter of Henry VII". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ^ Moore 2005, p. 159.

- ^ Moore 2005, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Moore 2005, pp. 169–185.

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Glendower, Owen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–121.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 199.

- ^ Williams 1987, pp. 217–226.

- ^ Williams 1987, pp. 268–273.

- ^ Davies 1987, p. 233.

Bibliography[]

- Ashbee, Jeremy (2007). Conwy Castle. Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-259-3.

- Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. Penguin Group. ISBN 0140284753.

- Davies, Rees R. (1987). Conquest, Coexistence, and Change: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821732-9.

- Davies, R. R. (2000), The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820878-2

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911). A History of Wales, from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. archive.org. Vol. II (2 ed.). Longmans, Green & Co. ISBN 978-1-334-06136-3.

- Maund, Kari L. (2006). The Welsh Kings: Warriors, Warlords, and Princes. searchworks.stanford.edu (3rd ed.). Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2973-1.

- Moore, David (2005). The Welsh Wars of Independence circa 410-1415. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-3321-9.

- Stephenson, David (1984). The Governance of Gwynedd. archive.org. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-0850-9.

- Taylor, Arnold (1997) [1953]. Caernarfon Castle and Town Walls (4th ed.). Cardiff: Cadw – Welsh Historic Monuments. p. 9. ISBN 1-85760-042-8.

- Wagner, John (2001). Encyclopedia of the Wars of the Roses. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-358-3.

- Williams, Glanmor (1987). Recovery, reorientation and reformation: Wales c.1415-1642. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821733-1.

University of Wales Press

- Williams, Gwyn A. (1985). When was Wales?: a history of the Welsh. Black Raven Press. ISBN 0-85159-003-9.

Additional sources[]

- Pennant, Thomas. A Tour of Wales. library.wales. Vol. 1–8.

- RCAHMW, An inventory of the ancient monuments in Glamorgan at Google Books

- RCAHMW, Wales and Monmoutshire at Google Books

- RCAHMW, An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Anglesey at Google Books

- 14th century in Wales

- 15th century in Wales

- Late Middle Ages