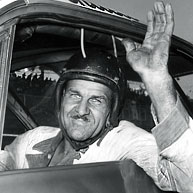

Wendell Scott

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (July 2013) |

| Wendell Scott | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Born | Wendell Oliver Scott August 29, 1921 Danville, Virginia | ||||||

| Died | December 23, 1990 (aged 69) Danville, Virginia | ||||||

| Cause of death | Spinal cancer | ||||||

| Achievements | First African-American in NASCAR First African-American winner in the Grand National Series | ||||||

| Awards | 1999 International Motorsports Hall of Fame inductee 2015 NASCAR Hall of Fame inductee | ||||||

| NASCAR Cup Series career | |||||||

| 495 races run over 13 years | |||||||

| Best finish | 6th (1966) | ||||||

| First race | 1961 Spartanburg 200 (Spartanburg) | ||||||

| Last race | 1973 National 500 (Charlotte) | ||||||

| First win | 1964 Jacksonville 200 (Jacksonville) | ||||||

| |||||||

| NASCAR Grand National East Series career | |||||||

| 17 races run over 2 years | |||||||

| Best finish | 7th () | ||||||

| First race | (Jacksonville) | ||||||

| Last race | (Hickory) | ||||||

| |||||||

Wendell Oliver Scott (August 29, 1921 – December 23, 1990) was an American stock car racing driver. He was one of the first African-American drivers in NASCAR, and the first African-American to win a race in the Grand National Series, NASCAR's highest level.

Scott began his racing career in local circuits and attained his NASCAR license in around 1953, making him the first African-American ever to compete in NASCAR.[1] He debuted in the Grand National Series on March 4, 1961, in Spartanburg, South Carolina.[2] On December 1, 1963, despite being considered part of the 1964 season, he won a Grand National Series race at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida, becoming the first black driver to win a race at NASCAR's premier level.[3] Scott's career was repeatedly affected by racial prejudice and problems with top-level NASCAR officials. However, his determined struggle as an underdog won him thousands of white fans and many friends and admirers among his fellow racers.[4] He was posthumously inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame in 2015.[5][6]

Background[]

Scott was born in Danville, Virginia. From boyhood, he wanted to be his own boss. In Danville, two industries dominated the local economy: cotton mills and tobacco-processing plants. Scott vowed to avoid that sort of boss-dominated life. "That mill's too much like a prison," he told a friend. "You go in and they lock a gate behind you and you can't get out until you've done your time." (This quotation and those that follow are from Hard Driving.) He began learning auto mechanics from his father, who worked as a driver and mechanic for two well-to-do white families. Scott and his sister Guelda were awed by their father's daring behind the wheel. "He frightened people to death," Guelda said. "They say he'd come through town just about touching the ground. After Scott started racing, all the old people would say the same thing: 'He's just like his daddy.'" Scott raced bicycles against white boys. In his neighborhood, he said, "I was the only black boy that had a bicycle." He became a daredevil on roller skates, speeding down Danville's steep hills on one skate. He dropped out of high school, became a taxi driver, and served as a mechanic in the segregated Army in Europe during World War II.[7] He married Mary Coles in 1943; they had seven children.[8]

After the war, he ran an auto-repair shop. As a sideline, he took up the dangerous and illegal pursuit of running moonshine whiskey. The police caught Scott only once, in 1949. Sentenced to three years probation, he continued making his late-night whiskey runs.[9]

Racing career[]

Scott was around thirty years old when he was sitting in the bleachers of local speedways, watching white men race. Up to then, he had lived his whole life under rules of segregation.

The Danville races were run by the Dixie Circuit, one of several regional racing organizations that competed with NASCAR during that era. Danville's events always made less money than the Dixie Circuit's races at other tracks. "We were a tobacco and textile town – people didn't have the money to spend," said Aubrey Ferrell, one of the organizers. The officials decided they would try an unusual, and unprecedented, promotional gimmick: They would recruit a Negro driver.

The next day, however, brought the first of many episodes of discrimination that would plague his racing career. Scott repaired his car with the help of a black mechanic, Hiram Kincaid, who previously worked with Ned Jarrett, and lived in North Carolina and towed it to a NASCAR-sanctioned race in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. But the NASCAR officials refused to let him compete. Black drivers were not allowed, they said. As he drove home, Scott recalled, "I had tears in my eyes." A few days later he went to another NASCAR event in High Point, North Carolina. Again, Scott said, the officials "just flat told me I couldn't race. They told me I could let a white boy drive my car. I told 'em weren't no damn white boy going to drive my car." Scott decided to avoid NASCAR for the time being and race with the Dixie Circuit and at other non-NASCAR speedways. He won his first race at Lynchburg, Virginia, only twelve days into his racing career. It was just a short heat race in the amateur class, but for Scott, the victory was like a barb on a hook. He knew that he had found his calling.

He ran as many as five events a week, mostly at Virginia tracks. Some spectators would shout racial slurs, but many others began rooting for him. Some prejudiced drivers would wreck him deliberately. They "just hammered on Wendell," former chief NASCAR photographer T. Taylor Warren said. "They figured he wasn't going to retaliate." And they were right—Scott felt that because of the racial atmosphere, he could not risk becoming involved in the fist-fights and dirty-driving paybacks that frequently took place among the white drivers.[10]

Many other drivers, however, came to respect Scott. They saw his skills as a mechanic and driver, and they liked his quiet, uncomplaining manner. They saw him as someone similar to themselves, another hard-working blue-collar guy swept up in the adrenaline rush of racing, not somebody trying to make a racial point. "He was a racer – you could look at somebody and tell whether they were a racer or not," said driver Rodney Ligon, who was also a moonshine runner. "Didn't nobody send him [to the track] to represent his race – he come down because he wanted to drive a damn racecar." Some white drivers became his close friends and also occasionally acted as his bodyguards.

Some Southern newspapers began writing positive stories about Scott's performance. He began the 1953 season on the northern Virginia circuit, for example, by winning a feature race in Staunton. Then he tied the Waynesboro qualifying record. A week later he won the Waynesboro feature, after placing first in his heat race and setting a new qualifying record. The Waynesboro News Virginian reported that Scott had become "recognized as one of the most popular drivers to appear here." The Staunton News Leader said he "has been among the top drivers in every race here."

Scott understood, though, that to rise in the sport, he somehow had to gain admission to the all-white ranks of NASCAR. He did not know NASCAR's celebrated founder and president, Bill France, who ran the organization like a czar. Instead, Scott found a way, essentially, to slip into NASCAR through a side door, without the knowledge or consent of anyone at NASCAR's Daytona Beach headquarters. He towed his racecar to a local NASCAR event at the old Richmond Speedway, a quarter-mile dirt oval, and asked the steward, Mike Poston, to grant him a NASCAR license. Poston, a part-timer, was not a powerful figure in NASCAR's hierarchy, but he did have the authority to issue licenses.

He asked Scott if he knew what he was getting into. "I told him we've never had any black drivers, and you're going to be knocked around," Poston said. "He said, 'I can take it.'" Poston approved Scott's license. Later he confided to Scott that officials at NASCAR headquarters had not been pleased with his decision. "He told me that when they found out at Daytona Beach that he had signed me up, they raised hell with him," Scott said.

Scott met Bill France for the first time in April 1954. The night before, Scott said, the promoter at a NASCAR event in Raleigh, North Carolina, had given gas money to all of the white drivers who came to the track but refused to pay Scott anything. Scott said he approached France in the pits at the Lynchburg speedway and told him what had happened. Even though France and the Raleigh promoter were friends, Scott said France immediately pulled some money out of his pocket and assured Scott that NASCAR would never treat him with prejudice. "He let me know my color didn't have anything to do with anything," Scott said. "He said, 'You're a NASCAR member, and as of now you will always be treated as a NASCAR member.' And instead of giving me fifteen dollars, he reached in his pocket and gave me thirty dollars."

Scott won dozens of races during his nine years in regional-level competition. His driving talent, his skill as a mechanic and his hard work earned him the admiration of thousands of white fans and many of his fellow racers, despite the racial prejudice that was widespread during the 1950s. In 1959 he won two championships. NASCAR awarded him the championship title for drivers of sportsman-class stock cars in the state of Virginia, and he also won the track championship in the sportsman class at Richmond's Southside Speedway. Even at this early stage of his racing, Scott would tell friends privately that his goal was to win races at the top level of NASCAR. For the rest of his career he would pursue a dream whose fulfillment depended heavily upon whether France backed up that promise.[11]

In 1961, he moved up to the Grand National Series. He achieved the most points for a debutant in 1961, but the Rookie of the Year award was given to another (white) driver.[7] In the 1964 season, he finished 15th in points, and on December 1 of that year, driving a Chevrolet Bel Air that he purchased from Ned Jarrett, he won a race on the half-mile dirt track at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida—the first (and, to date, only) Grand National event won by an African-American (Darrell Wallace Jr. recently became the second African-American driver in NASCAR's top 3 series to win with his 2013 Kroger 200 win at Martinsville). Scott passed Richard Petty, who was driving an ailing car, with 25 laps remaining for the win. Scott was not announced as the winner of the race at the time, presumably due to the racist culture of the time. Buck Baker, the second-place driver, was initially declared the winner, but race officials discovered two hours later that Scott had not only won, but was two laps in front of the rest of the field.[12] NASCAR awarded Scott the win two years later, but his family never actually received the trophy he had earned until 2010–47 years after the race, and 20 years after Scott had died.[3][13]

He continued to be a competitive driver despite his low-budget operation through the rest of the 1960s. Despite his successes, he never received commercial sponsorship.[7] In 1964, Scott finished 12th in points despite missing several races. Over the next five years, Scott consistently finished in the top ten in the point standings. He finished 11th in points in 1965, was a career-high 6th in 1966, 10th in 1967, and finished 9th in both 1968 and 1969. His top year in winnings was 1969 when he won $47,451.[14]

Scott was forced to retire due to injuries from a racing accident at Talladega, Alabama in 1973, although he did make one more start at Charlotte in which he finished 12th. He achieved one win and 147 top ten finishes in 495 career Grand National starts.

Scott died on December 23, 1990 in Danville, Virginia, having suffered from spinal cancer.[15]

Legacy[]

The film Greased Lightning, starring Richard Pryor as Scott, was loosely based on Scott's biography.

Mojo Nixon, a fellow Danville native, wrote a tribute song titled "The Ballad of Wendell Scott", which appears on Nixon and Skid Roper's 1986 album, Frenzy.

Scott was inducted as a member of the 2000 class of The Virginia Sports Hall of Fame and Museum located in Portsmouth, VA.[16] He also has a street named after him in his hometown of Danville.

Only seven other African-American drivers are known to have started at least one race in what is now the Cup Series: Elias Bowie, , George Wiltshire, , Willy T. Ribbs, Bill Lester, and most recently Bubba Wallace.[17]

As reported in the Washington Post, filmmaker John W. Warner began directing a documentary about Scott, titled The Wendell Scott Story, which was to be released in 2003 with narration by the filmmaker's father, former U.S. Senator John Warner but instead Warner created a four-set DVD entitled American Stock: The Golden Era of NASCAR: 1936-to-1971 which documents many racers including Scott.[18] The film included interviews with fellow race-car drivers, including Richard Petty. American Stock: The Golden Era of NASCAR: 1936-to-1971 is not listed on the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

Scott is prominently featured in the 1975 book The World's Number One, Flat-Out, All-Time Great Stock Car Racing Book, written by Jerry Bledsoe.

In April 2012, Scott was nominated for inclusion in the NASCAR Hall of Fame,[19] and was selected for induction in the 2015 class, in May 2014.[20] In January 2013, Scott was awarded his own historical marker in Danville, Virginia. The marker's statement will be “Persevering over prejudice and discrimination, Scott broke racial barriers in NASCAR, with a 13-year career that included 20 top five and 147 top ten finishes.”[21] Scott was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame on January 30, 2015.

Loosely based on him, a fictionalized version of Scott was given a minor role in the 2017 Pixar film Cars 3. He is portrayed by Isiah Whitlock Jr. in the form of an anthropomorphized car, with his name changed to River Scott.

A fictionalized version of Scott early in his career in 1955 was featured heavily on Timeless episode 2, season 2. Portrayed by Joseph Lee Anderson, Scott's history as a smuggler, mechanical and driving ability, perseverance, and past and future injustices due to racial discrimination were major themes of the episode.[22]

Motorsports career results[]

NASCAR[]

(key) (Bold – Pole position awarded by qualifying time. Italics – Pole position earned by points standings or practice time. * – Most laps led.)

Grand National Series[]

| NASCAR Grand National Series results | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Team | No. | Make | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | NGNC | Pts | Ref |

| 1961 | Scott Racing | 87 | Chevy | JSP | DAY | DAY | DAY | PIF 17 |

AWS | HMS | ATL | GPS | 32nd | 4726 | [23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | HBO 13 |

BGS 11 |

MAR 24 |

NWS 15 |

CLB 11 |

RCH | 15 |

DAR | RSD | ASP | CLT | PIF | GPS | BGS 21 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

DAY | CLB | MBS | BRI 24 |

BGS 7 |

AWS 24 |

RCH 16 |

SBO 16 |

DAR | HCY | RCH 14 |

CSF | ATL | MAR 28 |

NWS 13 |

CLT 22 |

BRI 16 |

GPS 8 |

HBO 15 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1962 | CON 14 |

AWS | DAY | DAY | DAY | CON 8 |

AWS 12 |

7 |

HBO 12 |

RCH 18 |

16 |

NWS 27 |

GPS 4 |

MBS 9 |

MAR 14 |

BGS 16 |

BRI 8 |

RCH 8 |

16 |

CON 3 |

DAR | PIF | CLT 30 |

ATL | BGS 6 |

AUG 9 |

RCH 14 |

SBO 10 |

DAY | CLB 9 |

ASH 9 |

GPS 3 |

AUG | 8 |

MBS 7 |

BRI 19 |

CHT 12 |

15 |

HCY 15 |

RCH 21 |

DTS 7 |

AUG 5 |

MAR 19 |

NWS 28 |

ATL | 22nd | 9906 | [24] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 89 | HUN 14 |

AWS 14 |

12 |

BGS 9 |

PIF 11 |

7 |

DAR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1963 | 34 | BIR | 10 |

RSD 18 |

DAY | DAY 25 |

DAY 26 |

PIF 5 |

AWS 12 |

HBO 23 |

ATL DNQ |

8 |

BRI 19 |

AUG 10 |

RCH 9 |

GPS 23 |

SBO 7 |

BGS 7 |

MAR 25 |

21 |

CLB 7 |

8 |

DAR | ODS 13 |

RCH 9 |

CLT 20 |

BIR 7 |

ATL 20 |

DAY 14 |

MBS 16 |

13 |

DTS 14 |

BGS 13 |

ASH 9 |

9 |

BRR 16 |

BRI | GPS 10 |

11 |

CLB 9 |

AWS 11 |

PIF 15 |

BGS 11 |

16 |

DAR | HCY 25 |

RCH 14 |

MAR 18 |

DTS 11 |

NWS 15 |

13 |

16 |

SBO 12 |

HBO 11 |

RSD | 15th | 14814 | [25] | ||||||||||

| 1964 | CON 17 |

18 |

JSP 1 |

15 |

RSD DNQ |

DAY | DAY 20 |

DAY 38 |

RCH 24 |

BRI 19 |

GPS 13 |

BGS 12 |

ATL | AWS 13 |

7 |

PIF 9 |

CLB 14 |

NWS 16 |

MAR 10 |

SVH | DAR | 12th | 19574 | [26] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ford | 4 |

9 |

SBO 7 |

CLT 9 |

GPS 12 |

ASH 6 |

ATL 12 |

CON 4 |

NSV 7 |

12 |

BIR 9 |

4 |

PIF 4 |

DAY 17 |

18 |

9 |

BRR 23 |

ISP 11 |

GLN 12 |

LIN 4 |

BRI 27 |

NSV 16 |

MBS 6 |

AWS 9 |

22 |

CLB 7 |

18 |

17 |

DAR DNQ |

HCY 9 |

RCH 21 |

ODS 6 |

HBO 4 |

MAR 26 |

5 |

NWS 14 |

22 |

6 |

27 |

JAC 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 55 | Chevy | 8 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1965 | 34 | Ford | RSD | DAY | DAY 7 |

DAY 20 |

PIF 8 |

AWS 17 |

RCH 20 |

HBO 23 |

ATL 35 |

GPS 10 |

NWS 11 |

MAR 16 |

CLB 9 |

BRI 5 |

DAR 15 |

7 |

BGS 6 |

8 |

13 |

ASH 14 |

9 |

NSV 4 |

14 |

ATL 9 |

GPS 7 |

MBS 16 |

15 |

DAY 13 |

ODS 21 |

ISP 7 |

GLN 14 |

BRI 7 |

13 |

11 |

AWS 8 |

13 |

PIF 4 |

AUG 9 |

CLB 8 |

DTS 14 |

5 |

16 |

DAR DNQ |

HCY 19 |

LIN 11 |

ODS 22 |

RCH 7 |

MAR 25 |

NWS 13 |

31 |

HBO 14 |

CAR 20 |

22 |

11th | 19902 | [27] | ||||||||||

| 70 | Ford | CLT 26 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 57 | Ford | DAR 10 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1966 | Scott Racing | 34 | Ford | 14 |

RSD | DAY | DAY 14 |

DAY 13 |

CAR 33 |

BRI 8 |

ATL | 14 |

CLB 9 |

GPS 20 |

BGS 18 |

NWS 4 |

MAR 18 |

DAR DNQ |

7 |

15 |

3 |

RCH 14 |

CLT 7 |

DTS 5 |

6 |

PIF 18 |

17 |

AWS 12 |

31 |

GPS | DAY 19 |

ODS 10 |

BRR 12 |

OXF 12 |

FON 9 |

ISP 13 |

BRI 27 |

SMR 12 |

NSV 9 |

ATL 7 |

CLB 13 |

AWS 6 |

BLV 14 |

BGS 6 |

DAR 24 |

HCY 6 |

RCH 7 |

8 |

MAR 38 |

NWS 11 |

CLT 17 |

6th | 21702 | [28] | ||||||||||||||

| 25 | DAR 26 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59 | Ford | CAR 35 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1967 | Scott Racing | 34 | Ford | 11 |

RSD | DAY | DAY 19 |

DAY 15 |

AWS 10 |

BRI 9 |

GPS 10 |

BGS 9 |

ATL 40 |

CLB 6 |

11 |

NWS 13 |

MAR 21 |

6 |

RCH 20 |

DAR 12 |

11 |

6 |

CLT 18 |

9 |

20 |

BIR 11 |

CAR 30 |

GPS 21 |

MGY 18 |

DAY 20 |

TRN 13 |

13 |

FDA 13 |

12 |

14 |

12 |

ATL 14 |

8 |

CLB 10 |

DAR 22 |

HCY 28 |

RCH 6 |

17 |

27 |

MAR 13 |

NWS 11 |

CAR 18 |

AWS 25 |

10th | 20700 | [29] | |||||||||||||||||

| 94 | Chevy | BRI 21 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 49 | Plymouth | CLT 28 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1968 | Scott Racing | 34 | Ford | 27 |

MGY 11 |

RSD DNQ |

DAY 17 |

RCH 9 |

ATL 25 |

HCY 19 |

GPS 8 |

CLB 13 |

NWS 14 |

MAR 19 |

AUG 8 |

AWS 23 |

BLV 23 |

LGY 12 |

CLT 23 |

17 |

11 |

11 |

BIR 12 |

CAR 18 |

GPS 8 |

DAY 24 |

ISP 11 |

10 |

FDA 8 |

TRN 12 |

BRI 19 |

26 |

22 |

ATL DNQ |

CLB 8 |

8 |

AWS 9 |

SBO 14 |

15 |

DAR 15 |

HCY 15 |

RCH 13 |

BLV 10 |

19 |

MAR 15 |

NWS 16 |

21 |

CLT 19 |

CAR 27 |

JFC 14 |

9th | 2685 | [30] | |||||||||||||||

| 50 | Plymouth | BRI 15 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Roy Tyner | 09 | Chevy | DAR 13 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gray Racing | 19 | Ford | ATL 27 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1969 | Scott Racing | 34 | Ford | MGR 13 |

MGY 19 |

RSD | DAY 26 |

DAY | DAY 29 |

CAR 20 |

14 |

BRI 17 |

CLB 12 |

13 |

GPS 11 |

RCH 24 |

NWS 15 |

MAR 12 |

AWS 10 |

DAR 15 |

9 |

10 |

CLT 35 |

11 |

22 |

MCH 12 |

10 |

GPS 12 |

6 |

DOV 7 |

21 |

TRN 13 |

21 |

BRI 19 |

11 |

14 |

ATL 19 |

MCH 27 |

9 |

BGS 9 |

AWS 12 |

DAR 17 |

HCY 16 |

RCH 8 |

TAL Wth |

CLB 8 |

MAR 19 |

NWS 19 |

14 |

AUG 17 |

CAR 9 |

14 |

MGR 14 |

TWS 18 |

9th | 3015 | [31] | |||||||||||

| 23 | Ford | ATL 27 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DAY 39 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Plymouth | CLT 17 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1970 | Scott Racing | 34 | Ford | RSD | DAY | DAY | DAY | RCH 10 |

CAR 8 |

9 |

ATL 15 |

BRI 21 |

TAL 20 |

NWS 24 |

CLB 11 |

DAR 16 |

9 |

10 |

CLT | 9 |

MAR 12 |

MCH 20 |

10 |

6 |

GPS 11 |

DAY 26 |

8 |

20 |

19 |

DOV 36 |

NCF 20 |

NWS 15 |

CLT | MAR DNQ |

MGR 21 |

CAR 20 |

LGY 19 |

14th | 2425 | [32] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| George Wiltshire | Dodge | RSD 35 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brooks Racing | 26 | Ford | TRN 25 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | BRI 18 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plymouth | 25 |

NSV 29 |

ATL 31 |

CLB 12 |

15 |

MCH 22 |

TAL 22 |

11 |

17 |

DAR 17 |

RCH 16 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1971 | Scott Racing | 34 | Ford | RSD | DAY | DAY 20 |

DAY DNQ |

RCH 23 |

CAR 15 |

15 |

BRI 15 |

ATL | CLB 14 |

GPS 21 |

24 |

NWS 21 |

MAR 17 |

DAR 13 |

10 |

TAL 19 |

14 |

6 |

CLT | DOV 27 |

MCH | HOU | GPS 8 |

DAY | BRI | 7 |

11 |

TRN 19 |

NSV 20 |

ATL 21 |

BGS 25 |

13 |

MCH 23 |

TAL DNQ |

CLB 12 |

17 |

DAR 20 |

MAR DNQ |

DOV 20 |

CAR 21 |

MGR 14 |

RCH 28 |

TWS 21 |

19th | 2180 | [33] | ||||||||||||||||||

| 96 | Chevy | TAL 26 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Plymouth | MAR 23 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 07 | Chevy | CLT 41 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scott Racing | 26 | Ford | NWS 17 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Winston Cup Series[]

| NASCAR Winston Cup Series results | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Team | No. | Make | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | NWCC | Pts | Ref | |||||||

| 1972 | Scott Racing | 34 | Ford | RSD | DAY DNQ |

RCH | ONT DNQ |

CAR DNQ |

ATL DNQ |

BRI | DAR | NWS | MAR 16 |

TAL DNQ |

DOV 20 |

MCH DNQ |

RSD | TWS 32 |

DAY | BRI | TRN 20 |

ATL DNQ |

TAL | MCH | NSV | DAR | RCH | DOV 16 |

MAR | NWS | CLT | CAR | TWS | 40th | 1317.5 | [34] | ||||||||

| Chevy | CLT 22 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1973 | Scott Racing | Ford | RSD | DAY | RCH | CAR | BRI | ATL | NWS | DAR 14 |

MAR | 61st | – | [35] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mercury | TAL 55 |

NSV | CLT | DOV | TWS | RSD | MCH | DAY | BRI | ATL | TAL | NSV | DAR | RCH | DOV | NWS | MAR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Faustina Racing | 5 | Dodge | CLT 12 |

CAR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Daytona 500[]

| Year | Team | Manufacturer | Start | Finish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Scott Racing | Chevrolet | 41 | 26 |

| 1964 | 40 | 38 | ||

| 1965 | Ford | 14 | 20 | |

| 1966 | 28 | 13 | ||

| 1967 | 38 | 15 | ||

| 1968 | 42 | 17 | ||

| 1969 | 49 | 29 | ||

| 1971 | Scott Racing | Ford | DNQ | |

| 1972 | DNQ | |||

References[]

- ^ Donovan, Brian (2008). Hard Driving: The Wendell Scott Story. Steerforth Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-1586421618. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Donovan, Brian (2008). Hard Driving: The Wendell Scott Story. Steerforth Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1586421618. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Coble, Don (October 18, 2010). "Wendell Scott's family gets long-lost trophy, and closure". Jacksonville.com. Waynesville, Georgia: The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Donovan, Brian (2008). Hard Driving: The Wendell Scott Story. Steerforth Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-1586421618. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Coble, Don (January 29, 2015). "Wendell Scott's induction into NASCAR Hall of Fame part of memorable legacy". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Price, Zenitha Prince (Senior AFRO Correspondent) (February 6, 2015). "First African American to Win NASCAR Premier Series Trophy Inducted into Hall of Fame".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/motorsport/53184543

- ^ http://autoracingdaily.com/mary-scott-widow-of-wendell-scott-passes-away/

- ^ Hinton, Ed. "When they finally let me run..." Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ T. Wills, John (August 29, 2017). "Remembering: NASCAR's First Black Driver And Hall Of Famer". Thought Provoking Perspectives. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ bruceyrock632 (October 27, 2013). "Wendell O Scott - Stories". Fold3. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "Wendell Scott: the Nascar Hall of Famer who conquered a tougher kind of race". The Guardian. January 31, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Ryan, Nate (May 22, 2014). "Ryan: A feel-good story for Wendell Scott but not for NASCAR". USA Today. Charlotte, North Carolina: USA Today. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ International Motorsports Hall of Fame Archived 2005-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Drivers remember Scott". The Gainesville Sun. Gainesville, FL. December 27, 1990. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ "Inductee Details – Virginia Sports Hall of Fame & Museum". Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Myrie, Donovan. "Meet the influential African-American drivers in NASCAR's Cup Series". ClickOrlando. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ FRYER, JENNA. "Documentary Traces NASCAR's Roots". Retrieved 24 February 2017 – via washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Demmons, Doug (April 12, 2012). "NASCAR does right by nominating Wendell Scott for Hall of Fame". The Birmingham News. Birmingham, AL. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ "NASCAR HALL OF FAME CLASS OF 2015 ANNOUNCED". NASCAR.com. May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Danville to get historical marker honoring NASCAR racer Wendell Scott Sr". WSLS. January 15, 2013. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Kaufman, Rachel (March 18, 2018). ""Timeless" Races Back to the '50s in 'Darlington'". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1961 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1962 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1963 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1964 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1965 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1966 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1967 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1968 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1969 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1970 NASCAR Grand National Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1971 NASCAR Winston Cup Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1972 NASCAR Winston Cup Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "Wendell Scott – 1973 NASCAR Winston Cup Results". Racing-Reference. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

External links[]

- Wendell Scott Foundation

- Wendell Scott driver statistics at Racing-Reference

- Omission of a Nascar Pioneer Stirs a Debate, New York Times, 8/19/09

- Wendell Scott at Find a Grave

- 1921 births

- 1990 deaths

- Sportspeople from Danville, Virginia

- Racing drivers from Virginia

- African-American racing drivers

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- NASCAR drivers

- American Speed Association drivers

- Deaths from spinal cancer

- Burials in Virginia

- African-American military personnel

- African-American sportsmen

- Deaths from cancer in Virginia