Where Eagles Dare

| Where Eagles Dare | |

|---|---|

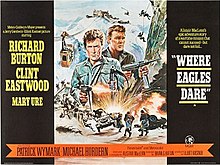

UK quad crown release poster by Howard Terpning | |

| Directed by | Brian G. Hutton |

| Screenplay by | Alistair MacLean |

| Based on | Where Eagles Dare 1966 novel by Alistair MacLean |

| Produced by | Elliott Kastner Jerry Gershwin |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Arthur Ibbetson |

| Edited by | John Jympson |

| Music by | Ron Goodwin |

| Color process | Metrocolor |

Production company | Winkast Film Productions |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 155 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6.2 million[1]—$7.7 million[2] |

| Box office | $21 million[3] |

Where Eagles Dare is a 1968 British Metrocolor World War II action film directed by Brian G. Hutton and starring Richard Burton, Clint Eastwood and Mary Ure. It follows a Secret Intelligence Service paratroop team raiding a castle. The film was distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, filmed in Panavision, and shot on location in Austria and Bavaria. Alistair MacLean wrote the screenplay, his first, at the same time that he wrote the novel of the same name. Both became commercial successes.

The film involved some of the top filmmakers of the day and is now considered a classic.[4] Major contributors included Hollywood stuntman Yakima Canutt, who as second unit director shot most of the action scenes; British stuntman Alf Joint who doubled for Burton in such sequences as the fight on top of the cable car; award-winning conductor and composer Ron Goodwin, who wrote the film score; and future Oscar-nominee Arthur Ibbetson, who worked on its cinematography.

Plot[]

In the winter of 1943–44, U.S. Army Brigadier General George Carnaby, a chief planner for the Western Front, is captured by the Germans. He is taken for interrogation to Schloß Adler, a mountaintop fortress accessible only by cable car. A team of seven Allied commandos, led by British Major John Smith of the Grenadier Guards and U.S. Army Ranger Lieutenant Morris Schaffer, is briefed by Colonel Turner and Vice Admiral Rolland of MI6. Disguised as German troops, they are to parachute into the German Alps, enter the castle, and rescue Carnaby before the Germans can interrogate him. After their transport plane drops them off, Smith secretly meets Mary Ellison, with whom he is in a relationship, and with Heidi Schmidt, their presence known only to him; Heidi has arranged for Mary to be a secretary at the castle in order for the commandos to gain access to it.

Although two of the team are mysteriously killed, Smith continues the operation, keeping Schaffer as a close ally and secretly updating Rolland and Turner by radio. He reveals that Carnaby is actually a corporal named Jones, an ex-actor and a lookalike of Carnaby trained to impersonate him. The Germans eventually surround the commandos in a gasthaus, and they are forced to surrender; Smith and Schaffer (being officers) are separated from the other three operatives, Thomas, Berkeley and Christiansen. Smith and Schaffer kill their captors, blow up a supply depot, and prepare an escape route for later use. They reach the castle by riding on the roof of a cable car and climb inside the castle when Mary lowers a rope.

German General Rosemeyer and Standartenführer Kramer are interrogating Carnaby when the three operative/prisoners, who are revealed to be agents working for the Germans, arrive. Shortly thereafter, Smith and Schaffer intrude, weapons drawn, but Smith then forces Schaffer to disarm. He identifies himself as Sturmbannführer Johann Schmidt of the SD of the SS intelligence branch, and a spy too. As proof, he discreetly shows the name of Germany's top agent in Britain to Kramer, who silently affirms it, and has Kramer call a high-ranking officer on Himmler's staff who testifies to Smith's identity as a German security officer. To test the three agents, Schmidt proposes that they write down the names of their fellow agents in Britain, to be compared to the list he has in his pocket. After the three finish their lists, Smith reveals that he was bluffing and that the lists were the mission's true objective.

Meanwhile, Mary is visited by Sturmbannführer von Hapen, a Gestapo officer who is attracted to her, but he becomes suspicious of flaws in her cover story. Leaving her, he happens upon the scene of Carnaby's interrogation just as Smith finishes his explanation; he puts everyone under arrest but is distracted when Mary arrives. Schaffer seizes the opportunity to kill von Hapen and the other German officers with his silenced pistol. The group then makes its escape, along with Jones and the three British commandos/German spies. Schaffer sets explosives to create diversions around the castle while Smith leads the group to the radio room where he informs Rolland of their success. During the escape, Thomas is sacrificed as a decoy; Berkeley and Christiansen try to flee, but are killed by Smith. The team reunites with Heidi on the ground, boarding a bus they had obtained earlier as an escape vehicle. They battle their way onto an airfield and escape in their transport where Turner has been waiting.

As Turner debriefs Smith about the mission, Smith reveals that the name Kramer confirmed as Germany's top agent in Britain was Turner's. Rolland had lured Turner and the others into participating so that MI6 could expose them; Smith's trusted partner Mary and the American Schaffer, who had no connection to MI6, had been assigned to the mission to ensure its success. Turner aims a gun at Smith, who reveals that Rolland has had the gun's firing pin removed. He permits Turner to jump out of the plane to his death to avoid being tried for treason and executed. Schaffer half-jokingly asks Smith to keep his next mission "an all-British operation".

Cast[]

- Richard Burton as Maj. John Smith / Maj. Johann Schmidt

- Clint Eastwood as Lt. Morris Schaffer

- Mary Ure as Mary Ellison

- Patrick Wymark as Col. Wyatt Turner

- Michael Hordern as Vice Admiral Rolland

- Donald Houston as Capt. Olaf Christiansen

- Peter Barkworth as Capt. Ted Berkeley

- William Squire as Capt. Lee Thomas

- Robert Beatty as Brig. Gen. George Carnaby / Cpl. Cartwright Jones

- Ingrid Pitt as Heidi Schmidt

- Brook Williams as Sgt. Harrod

- Neil McCarthy as Sgt. Jock MacPherson

- Vincent Ball as Wg Cdr. Cecil Carpenter

- Anton Diffring as Col. Paul Kramer

- Ferdy Mayne as Gen. Julius Rosemeyer

- Derren Nesbitt as Maj. von Hapen

- Philip Stone as Sky Tram Operator (uncredited)

- Victor Beaumont as Lt. Col. Weissner

- Guy Deghy as Maj. Wilhelm Wilner (uncredited)

- Derek Newark as SS Officer (uncredited)

Production[]

Development[]

Burton later said, "I decided to do the picture because Elizabeth's two sons said they were fed up with me making films they weren't allowed to see, or in which I get killed. They wanted me to kill a few people instead."[5]

Burton approached producer Elliott Kastner "and asked him if he had some super-hero stuff for me where I don't get killed in the end."[6]

The producer consulted MacLean and requested an adventure film filled with mystery, suspense, and action. Most of MacLean's novels had been made into films or were being filmed. Kastner persuaded MacLean to write a new story; six weeks later, he delivered the script, at that time entitled Castle of Eagles. Kastner hated the title, and chose Where Eagles Dare instead. The title[7] is from Act I, Scene III in William Shakespeare's Richard III: "The world is grown so bad, that wrens make prey where eagles dare not perch". Like virtually all of MacLean's works, Where Eagles Dare features his trademark "secret traitor", who must be unmasked by the end.

Kastner and co-producer Jerry Gershwin announced in July 1966 that they had purchased five MacLean scripts, starting with Where Eagles Dare and When Eight Bells Toll.[8] Brian Hutton had just made Sol Madrid for the producers and was signed to direct.[9]

Filming[]

Eastwood and Burton reportedly dubbed the film 'Where Doubles Dare' due to the amount of screen time in which stand-ins doubled for the cast during action sequences.[4] Filming began on 2 January 1968 in Austria and concluded in July 1968.[10] Eastwood received a salary of $800,000 while Burton received $1,200,000.[10][11] This is one of the first sound films to have used front projection effect.[12] This technology enabled filming of the scenes where the actors are on top of the cable car.

Eastwood initially thought the script written by MacLean was "terrible" and was "all exposition and complications." According to Derren Nesbitt, Eastwood requested that he be given less dialogue. Most of Schaffer's lines were given to Burton, whilst Eastwood handled most of the action scenes.[13] Director Hutton played to his actors' strengths, allowing for Burton's theatrical background to help the character of Smith and Eastwood's quiet demeanour to establish Schaffer. Eastwood took the part on the advice of his agent, who felt it would be interesting to see his client appear with someone with seniority. Eastwood and Burton got along well on set.[14]

Derren Nesbitt was keen to be as authentic as possible with his character Von Hapen. Whilst on location, he requested to meet a former member of the Gestapo to better understand how to play the character and to get the military regalia correct. He was injured on set whilst filming the scene in which Schaffer kills Von Hapen. The blood squib attached to Nesbitt exploded with such force that he was temporarily blinded, though he made a quick recovery.[13][15]

The filming was delayed due to the adverse weather in Austria. Shooting took place in winter and early spring of 1968, and the crew had to contend with blizzards, sub-zero temperatures and potential avalanches. Further delays were incurred when Richard Burton, well known for his drinking binges, disappeared for several days, with his friends Peter O'Toole, Trevor Howard and Richard Harris.[16] As part of his deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Clint Eastwood took delivery of a Norton P11 motorcycle, which he 'tested' at Brands Hatch racetrack,[17] accompanied by Ingrid Pitt, something that he had been forbidden from doing by Kastner for insurance purposes in case of injury or worse.[18]

Stuntman Alf Joint, who had played Capungo–the man who 007 electrocuted in the bathtub in Goldfinger–doubled and was stand-in for Richard Burton, and performed the famous cable car jump sequence, during which he lost three teeth.[16] Joint stated that at one point during production, Burton was so drunk that he knocked himself out while filming and Joint had to quickly fill in for him.[19] Derren Nesbitt observed that Burton was drinking as many as four bottles of vodka per day.[20]

Visitors to the set included Burton's wife Elizabeth Taylor, and Robert Shaw, who was then married to Mary Ure.[16]

At one point during filming, Burton was threatened at gunpoint by an overzealous fan, but fortunately danger was averted.[21]

The Junkers Ju 52 used to fly Smith and Schaffer's team into Austria and then make their escape at the end of the film was a Swiss Air Force Ju 52/3m, registration A-702.[22] It was destroyed in an accident on 4 August 2018, killing all 20 people on board.[23][24][25]

- The castle – Hohenwerfen Castle, Werfen, Austria; filmed in January 1968.

- Cable car – Feuerkogel Seilbahn at Ebensee, Austria; filmed in January 1968.

- Airport scenes – Flugplatz at Aigen im Ennstal, Austria; filmed in early 1968. The exact place of filming is the "Fiala-Fernbrugg" garrison, still used by HS Geschwader 2 and FlAR2/3rd Bat. of the Austrian Army. The big rocky mountain in the background of the airfield is the Grimming mountains, about 40 km east of the "Hoher Dachstein", or about 80 km east and 10 km south from Werfen.[29]

- The village – Lofer, Austria; filmed in January 1968.

- Other scenes – MGM-British Studios, Borehamwood, England; filmed in spring 1968.[30]

Reception[]

Where Eagles Dare received a Royal premiere at the Empire, Leicester Square cinema on 22 January 1969 with Princess Alexandra in attendance. Of the stars of the film, only Clint Eastwood was not present as he was filming Two Mules for Sister Sara in Mexico.[31] The film was a huge success,[32] earning $6,560,000 at the North American box office during its first year of release.[33] It was the seventh-most popular film at the UK box office in 1969, and 13th in the US.[34]

Though many critics found the plot somewhat confusing, reviews of the film were generally positive. Vincent Canby of the New York Times gave a positive review, praising the action scenes and cinematography.[35] Likewise, Variety praised the film, describing it as 'thrilling'.[36] The film was particularly lucrative for Richard Burton, who earned a considerable sum in royalties through television repeats and video sales.[37] Where Eagles Dare had its first showing on British television on 26 December 1979 on BBC1.

Mad Magazine published a satire of the film in its October 1969 issue under the title "Where Vultures Fare." In 2009 Cinema Retro released a special issue dedicated to Where Eagles Dare which detailed the production and filming of the film.[38]

Years after its debut, Where Eagles Dare enjoys a reputation as a classic[4] and is considered by many as one of the best war films of all time.[39][40]

Soundtrack[]

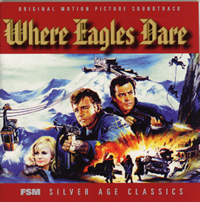

| Where Eagles Dare | |

|---|---|

| |

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 4 January 2005 |

| Genre | Soundtracks Film music |

| Length | 74:07 |

| Label | Film Score Monthly |

| Producer | Lukas Kendall |

The score was composed by Ron Goodwin. A soundtrack was released on Compact Disc in 2005 by Film Score Monthly, of the Silver Age Classics series, in association with Turner Entertainment. It was a two-disc release, the first CD being the film music, the second the film music for Operation Crossbow and source music for Where Eagles Dare. The release has been limited to 3,000 pressings.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Main Title" | |

| 2. | "Before Jump/Death of Harrod" | |

| 3. | "Mary and Smith Meet/Sting on Castle/Parade Ground" | |

| 4. | "Preparation in Luggage Office/Fight in Car" | |

| 5. | "The Booby Trap" | |

| 6. | "Ascent on the Cable Car" | |

| 7. | "Death of Radio Engineer and Helicopter Pilot" | |

| 8. | "Checking on Smith/Names in Notebook" | |

| 9. | "Smith Triumphs Over Nazis" | |

| 10. | "Intermission Playout" | |

| 11. | "Entr'Acte" | |

| 12. | "Encounter in the Castle" | |

| 13. | "Journey Through the Castle Part 1" | |

| 14. | "Journey Through the Castle Part 2" | |

| 15. | "Descent and Fight on the Cable Car" | |

| 16. | "Escape from the Cable Car" | |

| 17. | "Chase, Part 1 and 2" | |

| 18. | "The Chase in the Airfield" | |

| 19. | "The Real Traitor" | |

| 20. | "End Playout" |

Novel[]

The principal difference is that the 1966 novel by Alistair MacLean is less violent. One scene during the escape from the castle where Smith saves a German guard from burning to death presaged the non-lethal thriller vein that MacLean would explore in his later career. In the novel the characters are more clearly defined and slightly more humorous than their depictions in the film, which is fast-paced and has sombre performances from Burton and Eastwood at its centre. Three characters are differently named in the novel: Ted Berkeley is called Edward Carraciola, Jock MacPherson is called Torrance-Smythe, and Major von Hapen is instead Captain von Brauchitsch. A budding love story between Schaffer and Heidi was also cut.[41] Indeed, in the novel Schaffer asks the pilot to arrange for a priest to meet them at the airport.

In the book the group is flown into Germany on board an RAF Avro Lancaster, whereas in the film they are transported in a Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 52. While in the film Kramer, Rosemeyer, and Von Hapen are shot dead by Schaffer and Smith, in the novel they are just given high doses of nembutal. In the book Thomas, Carraciola, and Christiansen attempt to escape in the cable car with Smith on the roof. Carraciola is crushed by the steel suspension arm of the cable car while struggling with Smith on the roof; Thomas and Christiansen fall to their deaths after Smith blows the cable car up with plastic explosive. In the film Christiansen is killed and Berkeley (Carraciola in the novel) incapacitated by Smith on the cable car (he dies apparently when the cable car explodes), and Thomas is shot and killed by a German soldier while climbing down a rope.[42]

In popular culture[]

In 1979, cult punk act The Misfits released a single featuring a song named after the film.

The British heavy metal band Iron Maiden recorded a song called "Where Eagles Dare" on their 1983 album Piece of Mind. The live performance features Bruce Dickinson in snow camouflage and Richard Burton's "Broadsword calling Danny Boy" message as an intro.[43]

References[]

Notes

- ^ Webster, Jack (1991). Alistair MacLean: A Life. Chapmans. p. 133.

- ^ "Metro-Goldwyn Omits Dividend; O'Brien Resigns: Board Cites Possible Loss Of Up to $19 Million in The Current Fiscal Year Bronfman Named Chairman". Wall Street Journal. 27 May 1969. p. 2.

- ^ Hughes, p.194

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Where Eagles Dare". TCM. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "3 Companies Offer to Bankroll Burton Film". Los Angeles Times. 22 February 1968. p. d16.

- ^ Aba, Marika (21 July 1968). "The Burtons... 'Just Another Working Couple'". Los Angeles Times. p. c18.

- ^ "BROADSWORD CALLING DANNY-BOY … the making of WHERE EAGLES DARE". Film Review 1998: republished in The Cellulord is Watching. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ Martin, Betty (30 July 1966). "Gene Kelly to Do 'Married'". Los Angeles Times. p. 18.

- ^ "'Isadora' Shooting Under Way". Los Angeles Times. 7 September 1967. p. d20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hughes, pp.191–192

- ^ Munn, p. 79

- ^ Lightman, Herb A. "Front Projection for "2001: A Space Odyssey"". American Cinematographer.

- ^ Jump up to: a b A Conversation with Derren Nesbitt. "Major von Hapen" in "Where Eagles Dare". YouTube (10 June 2013). Retrieved on 2015-11-20.

- ^ "The Clint Eastwood Archive: Eastwood Interviewed # 03 Clint on Clint Empire Magazine November 2008". 15 December 2009.

- ^ "Actor Injured as Burton Fires 'Shot'". Chicago Tribune. 25 April 1968. p. b30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c the cellulord is watching: WHERE EAGLES DARE. Cellulord.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Norton Motors homepage". Nortonmotors.de. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ If Only. Ingridpitt.net. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ http://cellulord.blogspot.com/2010/01/where-eagles-dare_31.html?m=1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ The Daily Telegraph

- ^ "The Clint Eastwood Archive: Where Eagles Dare: Terror behind the scenes!". 3 January 2018.

- ^ Where Eagles Dare – The Internet Movie Plane Database. Impdb.org (30 January 2015). Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ Siddique, Haroon (5 August 2018). "Swiss Alps plane crash leaves all 20 passengers and crew dead". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "20 dead in Junkers Ju 52 crash in Switzerland". Airliners.Ne. 4 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "Aviation Safety Network". Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ http://thestudiotour.com/mgmborehamwood/backlot.shtml

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20160228200027/http://xtremelaser.com/MGMBRITISHSTUDIOS/gallery/where_eagles_dare/000134.htm

- ^ http://mitteleuropa.ihostfull.com/filmlocations_where_eagles_dare.html

- ^ (Trivia). Where Eagles Dare.com (3 January 1997). Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ Where Eagles Dare (1968). Mitteleuropa.x10.mx. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Where Eagles Dare - Memorabilia UK".

- ^ Preview: a young director and his $9 million cliff-hanger: 'Chat' pictures 'What's that?' 'Positive' alternatives By Roderick Nordell. The Christian Science Monitor 7 Mar 1969: 4.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1969", Variety, 7 January 1970 p. 15

- ^ "The World's Top Twenty Films." Sunday Times [London, UK] 27 September 1970: 27. The Sunday Times Digital Archive. accessed 5 April 2014

- ^ "Screen: In the War Tradition, 'Where Eagles Dare'". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Where Eagles Dare". January 1969.

- ^ Richard Burton classic Where Eagles Dare funds new literary prize. Wales Online. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ "WHERE EAGLES DARE": THE UPDATED AND REVISED CINEMA RETRO MOVIE CLASSICS ISSUE NOW SHIPPING WORLDWIDE! – Celebrating Films of the 1960s & 1970s. Cinemaretro.com. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Where Eagles Dare: No 24 best action and war film of all time". The Guardian. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Neil Armstrong0 (3 July 2018). "Where Eagles Dare at 50: how Burton and Eastwood – plus a lot of vodka – made the world's favourite war movie". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018.

- ^ "I capture the castle". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "The War Movie Buff: BOOK/MOVIE: Where Eagles Dare (1967/1968)". 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Iron Maiden – Piece of Mind Billboard Albums". AllMusic. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

Bibliography

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- Munn, Michael (1992). Clint Eastwood: Hollywood's Loner. London: Robson Books. ISBN 0-86051-790-X.

- Dyer, Geoff (2018). Broadsword Calling Danny Boy. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0141987620.

External links[]

- Where Eagles Dare at IMDb

- Where Eagles Dare at the TCM Movie Database

- Where Eagles Dare at AllMovie

- Where Eagles Dare at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Where Eagles Dare at Box Office Mojo

- Where Eagles Dare at Rotten Tomatoes

- Film review at AlistairMacLean.com

- Where Eagles Dare Website

- Film Locations used in Where Eagles Dare

- Film Production for Where Eagles Dare

- 1968 films

- English-language films

- 1960s action war films

- British action war films

- British films

- British war adventure films

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on military novels

- Films based on works by Alistair MacLean

- 1960s war adventure films

- Novels set during World War II

- World War II spy films

- Films directed by Brian G. Hutton

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films set in 1943

- Films set in 1944

- Films set in Austria

- Films set in Germany

- Films set in the Alps

- Films shot in Austria

- Films shot in Bavaria

- 1967 British novels

- Novels by Alistair MacLean

- William Collins, Sons books

- Films scored by Ron Goodwin

- Films produced by Elliott Kastner

- Films set in castles

- British World War II films