William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman | |

|---|---|

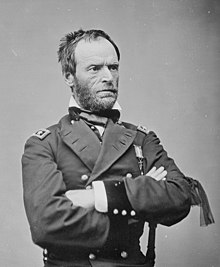

Portrait by Mathew Brady of Sherman as a major general in May 1865. The black ribbon of mourning on his left arm is for President Lincoln. | |

| Commanding General of the U.S. Army | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – November 1, 1883 | |

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Succeeded by | Philip Sheridan |

| Acting United States Secretary of War | |

| In office September 6, 1869 – October 25, 1869 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | John Aaron Rawlins |

| Succeeded by | William W. Belknap |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Tecumseh Sherman February 8, 1820 Lancaster, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | February 14, 1891 (aged 71) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Calvary Cemetery, St. Louis, Missouri |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Eleanor Boyle Ewing

(m. 1850; died 1888) |

| Education | United States Military Academy |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | American Civil War

|

| Awards | Thanks of Congress[1] |

William Tecumseh Sherman (/tɛˈkʌmsə/ te-KUM-sə; February 8, 1820 – February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), receiving recognition for his command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the scorched earth policies that he used against the Confederate States.[2] British military theorist and historian B. H. Liddell Hart declared that Sherman was "the first modern general".[3]

Born in Ohio to a politically prominent family, Sherman graduated in 1840 from the United States Military Academy at West Point. He interrupted his military career in 1853 to pursue private business ventures, and at the outbreak of the Civil War he was superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy (now Louisiana State University). Sherman commanded a brigade of volunteers at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861 before being transferred to the Western Theater. Stationed in Kentucky, his pessimism about the outlook of the war led to a nervous breakdown that required him to be briefly put on leave. He recovered by forging a close partnership with General Ulysses S. Grant. Sherman served under Grant in 1862 and 1863 during the battles of forts Henry and Donelson, the Battle of Shiloh, the campaigns that led to the fall of the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, as well as the Chattanooga campaign that culminated with the routing of the Confederate armies in the state of Tennessee.

In 1864, Sherman succeeded Grant as the Union commander in the Western Theater. He led the capture of the strategic city of Atlanta, a military success that contributed to the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln. Sherman's subsequent march through Georgia and the Carolinas involved little fighting but large-scale destruction of cotton plantations and other infrastructure, a systematic policy intended to undermine the ability and willingness of the Confederacy to continue fighting. Sherman accepted the surrender of all the Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida in April 1865, but the terms that he negotiated were considered too lenient by US Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who ordered General Grant to modify them.

When Grant became president of the United States in March 1869, Sherman succeeded him as Commanding General of the Army. Sherman served in that capacity from 1869 until 1883 and was responsible for the U.S. Army's engagement in the Indian Wars. He steadfastly refused to be drawn into politics and in 1875 published Memoirs, one of the best-known first-hand accounts of the Civil War.

Early life

Sherman was born in 1820 in Lancaster, Ohio, near the banks of the Hocking River. His father, Charles Robert Sherman, a successful lawyer who sat on the Ohio Supreme Court, died unexpectedly in 1829. He left his widow, Mary Hoyt Sherman, with eleven children and no inheritance. After his father's death, the nine-year-old Sherman was raised by a Lancaster neighbor and family friend, attorney Thomas Ewing, Sr., a prominent member of the Whig Party who served as U.S. senator from Ohio and as the first Secretary of the Interior. Sherman was distantly related to American founding father Roger Sherman and grew to admire him.[4]

Sherman's older brother Charles Taylor Sherman became a federal judge. One of his younger brothers, John Sherman, served as a U.S. congressman, senator, and cabinet secretary. Another younger brother, Hoyt Sherman, was a successful banker. Two of his foster brothers served as major generals in the Union Army during the Civil War: Hugh Boyle Ewing, later an ambassador and author, and Thomas Ewing, Jr., who would serve as defense attorney in the military trials of the Lincoln conspirators. Sherman would marry his foster sister, Ellen Boyle Ewing, at age 30 and have eight children with her.[5]

Sherman's given names

Sherman's unusual given name has always attracted attention.[6] He reported that his middle name came from his father having "caught a fancy for the great chief of the Shawnees, 'Tecumseh'".[7] According to a 1932 biography written by Lloyd Lewis, Sherman was originally named only "Tecumseh", acquiring the name "William" at the age of nine or ten, when he was baptized by the Roman Catholic rite at the behest of his foster family. In this account, repeated by later authors, Sherman was baptized in the Ewing home by a Dominican priest who found the pagan name "Tecumseh" unsuitable and instead named the child "William" after the saint on whose feast day the baptism took place.[8] However, Sherman wrote in his Memoirs that his father named him "William Tecumseh". He was baptized by a Presbyterian minister as an infant and was probably given the first name "William" at that time.[9] As an adult, Sherman signed all his correspondence —including to his wife— "W. T. Sherman".[10] His friends and family called him "Cump".[11]

Military training and service

Senator Ewing secured an appointment for the 16-year-old Sherman as a cadet in the United States Military Academy at West Point.[12] Sherman roomed and became good friends with another important future Civil War General, George H. Thomas. While there Sherman excelled academically, but he treated the demerit system with indifference. Fellow cadet William Rosecrans remembered Sherman at West Point as "one of the brightest and most popular fellows" and "a bright-eyed, red-headed fellow, who was always prepared for a lark of any kind".[13] About his time at West Point, Sherman says only the following in his Memoirs:

At the Academy I was not considered a good soldier, for at no time was I selected for any office, but remained a private throughout the whole four years. Then, as now, neatness in dress and form, with a strict conformity to the rules, were the qualifications required for office, and I suppose I was found not to excel in any of these. In studies I always held a respectable reputation with the professors, and generally ranked among the best, especially in drawing, chemistry, mathematics, and natural philosophy. My average demerits, per annum, were about one hundred and fifty, which reduced my final class standing from number four to six.[14]

Upon graduation in 1840, Sherman entered the army as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery and saw action in Florida in the Second Seminole War against the Seminole tribe. He was later stationed in Georgia and South Carolina. As the foster son of a prominent Whig politician, in Charleston the popular Lt. Sherman moved within the upper circles of Old South society.[15]

While many of his colleagues saw action in the Mexican–American War, Sherman was assigned to administrative duties in the captured territory of California. Along with fellow lieutenants Henry Halleck and Edward Ord, Sherman embarked from New York City on the 198-day journey around Cape Horn, aboard the converted sloop USS Lexington. During that voyage, Sherman grew close to Halleck and Ord, and in his Memoirs relate a hike with Halleck to the summit of Corcovado, overlooking Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. Sherman and Ord reached the town of Yerba Buena, in California, two days before its name was changed to San Francisco. In 1848, Sherman accompanied the military governor of California, Col. Richard Barnes Mason, in the inspection that officially confirmed that gold had been discovered in the region, thus inaugurating the California Gold Rush.[16] At John Augustus Sutter Jr.’s request, Sherman assisted Capt. William H. Warner in surveying the new city of Sacramento, laying its street grid in 1848.[17]

Sherman earned a brevet promotion to captain for his "meritorious service", but his lack of a combat assignment discouraged him and may have contributed to his decision to resign his commission. He would eventually become one of the few high-ranking officers of the US Civil War who had not fought in Mexico.[18]

Marriage and business career

In 1850, Sherman was promoted to the substantive rank of captain and on May 1 of that year he married his foster sister, Ellen Boyle Ewing, four years his junior. Rev. James A. Ryder, President of Georgetown College, officiated the Washington D.C. ceremony. President Zachary Taylor, Vice President Millard Fillmore and other political luminaries attended the ceremony. Thomas Ewing was serving as Secretary of the Interior at the time.[19] Like her mother, Ellen Ewing Sherman was a devout Roman Catholic, and the Shermans' eight children were reared in that faith. In 1864, Ellen would take up temporary residence in South Bend, Indiana, to have her young family educated at the University of Notre Dame and St. Mary's College, both of them Catholic institutions.[20]

In 1853, Sherman resigned his captaincy and became manager of the San Francisco branch of the St. Louis-based bank Lucas, Turner & Co. He survived two shipwrecks and floated through the Golden Gate on the overturned hull of a foundering lumber schooner.[21] Sherman suffered from stress-related asthma because of the city's aggressive business culture.[22] Late in life, regarding his time in a San Francisco experiencing a frenzy of real estate speculation, Sherman recalled: "I can handle a hundred thousand men in battle, and take the City of the Sun, but am afraid to manage a lot in the swamp of San Francisco."[23] In 1856, during the vigilante period, he served briefly as a major general of the California militia.[24]

Sherman's San Francisco branch closed in May 1857, and he relocated to New York City on behalf of the same bank. When the bank failed during the financial Panic of 1857, he closed the New York branch. In early 1858, he returned to California to wrap up the bank's affairs there. Later in 1858, he moved to Leavenworth, Kansas, where he opened a law practice and other ventures without much success.[25]

Military college superintendent

In 1859, Sherman accepted a job as the first superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy in Pineville, Louisiana, a position he sought at the suggestion of Major D. C. Buell and obtained thanks to the support of General George Mason Graham.[27] Sherman proved an effective and popular leader of the institution, which would later become Louisiana State University (LSU).[28] Colonel Joseph P. Taylor, the brother of the late President Zachary Taylor, declared that "if you had hunted the whole army, from one end of it to the other, you could not have found a man in it more admirably suited for the position in every respect than Sherman."[29]

Sherman's younger brother, John Sherman, was one of the founders of the Republican Party and, from his seat in the US Congress, a prominent advocate against slavery. Before the Civil War, however, the more conservative W. T. Sherman had expressed some sympathy for the white Southerners' defense of their agrarian system, including the institution of slavery. On the other hand, W. T. Sherman was adamantly opposed to the secession of the southern states. In Louisiana, he became a close friend of Professor David F. Boyd, a native of Virginia and an enthusiastic secessionist. Boyd later recalled witnessing that, when news of South Carolina's secession from the United States reached them at the Seminary, "Sherman burst out crying, and began, in his nervous way, pacing the floor and deprecating the step which he feared might bring destruction on the whole country."[30] In what some authors have seen as an accurate prophecy of the conflict that would engulf the United States during the next four years,[31] Boyd recalled Sherman declaring:

You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it... Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth—right at your doors. You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.[32]

In January 1861, as more Southern states seceded from the Union, Sherman was required to accept receipt of arms surrendered to the Louisiana State Militia by the U.S. Arsenal at Baton Rouge. Instead of complying, he resigned his position as superintendent, declaring to the governor of Louisiana that "on no earthly account will I do any act or think any thought hostile ... to the ... United States."[33]

St. Louis interlude

Sherman departed Louisiana and traveled to Washington, D.C., possibly in the hope of securing a position in the army. At the White House, Sherman met with Abraham Lincoln a few days after his inauguration as President of the United States. In the course of that meeting, Sherman expressed serious concerns about the North's poor state of preparedness for the looming civil war, but he found Lincoln unresponsive.[34]

Sherman then moved to St. Louis to become president of a streetcar company called the St. Louis Railroad. Thus, he was living in the border state of Missouri as the secession crisis reached its climax. While trying to hold himself aloof from political controversy, he observed first-hand the efforts of Congressman Frank Blair, who later served under Sherman, to keep Missouri in the Union. In early April, he declined an offer from the Lincoln administration to take a position in the War Department that could have led to an appointment as Assistant Secretary of War.[35]

After the April 12–13 bombardment of Fort Sumter and its subsequent capture by the Confederacy, Sherman hesitated about committing to military service and ridiculed Lincoln's call for 75,000 three-month volunteers to quell secession, reportedly saying: "Why, you might as well attempt to put out the flames of a burning house with a squirt-gun."[36] In May, however, he offered himself for service in the regular army. Senator John Sherman (his younger brother and a political ally of President Lincoln) and other connections in Washington helped him to obtain a commission in the US army.[37] On June 3, he wrote that "I still think it is to be a long war —very long— much longer than any Politician thinks."[38]

Civil War service

First commissions and Bull Run

Sherman was first commissioned as colonel of the 13th U.S. Infantry Regiment, effective May 14, 1861. This was a new regiment yet to be raised, and Sherman's first command was actually of a brigade of three-month volunteers who fought in the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861.[39] This was one of the five brigades in the division commanded by General Daniel Tyler, which was in turn one of the five divisions in the Army of Northeastern Virginia under General Irvin McDowell. The battle ended in a disastrous defeat for the Union, putting an end to the hopes for a rapid resolution of the conflict over secession. Sherman was one of the few Union officers to distinguish himself in the field and historian Donald L. Miller has characterized Sherman's performance at Bull Run as "exemplary".[40] During the fighting, Sherman was grazed by bullets in the knee and shoulder. According to British military historian Brian Holden-Reid, "if Sherman had committed tactical errors during the attack, he more than compensated for these during the subsequent retreat".[41] Holden-Reid also concluded that Sherman "might have been as unseasoned as the men he commanded, but he had not fallen prey to the naïve illusions nursed by so many on the field of First Bull Run."[42]

The outcome at Bull Run caused Sherman to question his own judgment as an officer and the capabilities of his volunteer troops. However, Sherman impressed Abraham Lincoln during the President's visit to the troops on July 23, and Lincoln promoted Sherman to brigadier general of volunteers effective May 17, 1861, with seniority in rank to Ulysses S. Grant, his future commander.[43] Sherman was then assigned to serve under Robert Anderson in the Department of the Cumberland in Louisville, Kentucky. In October, Sherman succeeded Anderson in command of that department. In his memoirs, Sherman would later write that he saw that new assignment as breaking a promise from President Lincoln that he would not be given such a prominent leadership position.[44]

Kentucky and breakdown

Having succeeded Anderson at Louisville, Sherman now had principal military responsibility for Kentucky, a border state in which Confederate troops held Columbus and Bowling Green, and were also present near the Cumberland Gap.[45] He became exceedingly pessimistic about the outlook for his command and he complained frequently to Washington, D.C. about shortages, while providing exaggerated estimates of the strength of the rebel forces and requesting inordinate numbers of reinforcements. Critical press reports about Sherman began to appear after the secretary of war, Simon Cameron, visited Louisville in October of 1861. In early November, Sherman asked to be relieved of his command.[46] He was promptly replaced by Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell and transferred to St. Louis, Missouri. In December, he was put on leave by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, commander of the Department of the Missouri, who considered him unfit for duty. Sherman went to Lancaster, Ohio, to recuperate. While he was at home, his wife Ellen wrote to his brother, Senator John Sherman, seeking advice. She complained of "that melancholy insanity to which your family is subject".[47] In his private correspondence, Sherman later wrote that the concerns of command "broke me down" and admitted to having contemplated suicide.[48] His problems were compounded when the Cincinnati Commercial described him as "insane".[49]

By mid-December 1861 Sherman had recovered sufficiently to return to service under Halleck in the Department of the Missouri. In March, Halleck's command was redesignated the Department of the Mississippi and enlarged to unify command in the West. Sherman's initial assignments were rear-echelon commands, first of an instructional barracks near St. Louis and then in command of the District of Cairo.[50] Operating from Paducah, Kentucky, he provided logistical support for the operations of Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to capture Fort Donelson in February of 1862. Grant, the previous commander of the District of Cairo, had just won a major victory at Fort Henry and been given command of the ill-defined District of West Tennessee. Although Sherman was technically the senior officer, he wrote to Grant, "I feel anxious about you as I know the great facilities [the Confederates] have of concentration by means of the River and R Road, but [I] have faith in you—Command me in any way."[51]

Shiloh

After Grant captured Fort Donelson, Sherman got his wish to serve under Grant when he was assigned on March 1, 1862, to the Army of West Tennessee as commander of the 5th Division.[52] His first major test under Grant was at the Battle of Shiloh. The massive Confederate attack on the morning of April 6, 1862, took most of the senior Union commanders by surprise. Sherman had dismissed the intelligence reports received from militia officers, refusing to believe that Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston would leave his base at Corinth. He took no precautions beyond strengthening his picket lines, and refused to entrench, build abatis, or push out reconnaissance patrols. At Shiloh, he may have wished to avoid appearing overly alarmed in order to escape the kind of criticism he had received in Kentucky. He had written to his wife that, if he took more precautions, "they'd call me crazy again".[53]

Despite being caught unprepared by the attack, Sherman rallied his division and conducted an orderly, fighting retreat that helped avert a disastrous Union rout. Finding Grant at the end of the day sitting under an oak tree in the darkness and smoking a cigar, Sherman felt, in his words, "some wise and sudden instinct not to mention retreat". In what would become one of the most notable conversations of the war, Sherman said simply: "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day, haven't we?" After a puff of his cigar, Grant replied calmly: "Yes. Lick 'em tomorrow, though."[54] Sherman proved instrumental to the successful Union counterattack of April 7, 1862. At Shiloh, Sherman was wounded twice—in the hand and shoulder—and had three horses shot out from under him. His performance was praised by Grant and Halleck and after the battle he was promoted to major general of volunteers, effective May 1, 1862.[52]

Beginning in late April, a Union force of 100,000 moved slowly against Corinth, under Halleck's command with Grant relegated to second-in-command; Sherman commanded the division on the extreme right of the Union's right wing (under George Henry Thomas). Shortly after the Union forces occupied Corinth on May 30, Sherman persuaded Grant not to leave his command, despite the serious difficulties he was having with Halleck. Sherman offered Grant an example from his own life, "Before the battle of Shiloh, I was cast down by a mere newspaper assertion of 'crazy', but that single battle gave me new life, and I'm now in high feather." He told Grant that, if he remained in the army, "some happy accident might restore you to favor and your true place".[55] In July, Grant's situation improved when Halleck left for the East to become general-in-chief, and Sherman became the military governor of occupied Memphis.[56]

Vicksburg

According to historian John D. Winters's The Civil War in Louisiana (1963), at this time Sherman

... had yet to display any marked talents for leadership. Sherman, beset by hallucinations and unreasonable fears and finally contemplating suicide, had been relieved from command in Kentucky. He later began a new climb to success at Shiloh and Corinth under Grant. Still, if he muffed his Vicksburg assignment, which had begun unfavorably, he would rise no higher. As a man, Sherman was an eccentric mixture of strength and weakness. Although he was impatient, often irritable and depressed, petulant, headstrong, and unreasonably gruff, he had solid soldierly qualities. His men swore by him, and most of his fellow officers admired him.[57]

Sherman's military record in 1862–63 was mixed. In December 1862, forces under his command suffered a severe repulse at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, just north of Vicksburg, Mississippi.[58] Soon after, his XV Corps was ordered to join Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand in his successful assault on Arkansas Post.[59] Grant, who was on poor terms with McClernand, regarded this as a politically motivated distraction from the efforts to take Vicksburg, but Sherman had targeted Arkansas Post independently and considered the operation worthwhile.[60]

Sherman initially expressed reservations about the wisdom of Grant's unorthodox strategy for the Vicksburg campaign in the spring of 1863, which called for the invading Union army to separate from its supply train and subsist by foraging.[61] However, he submitted fully to Grant's leadership and the campaign cemented Sherman's close personal ties to Grant.[62] During the long and complicated maneuvers against Vicksburg, one newspaper complained that the "army was being ruined in mud-turtle expeditions, under the leadership of a drunkard [Grant], whose confidential adviser [Sherman] was a lunatic".[63] The final fall of the besieged city of Vicksburg was a major strategic victory for the Union, since it put navigation along the Mississippi River entirely under the Union army's control and effectively cut off Texas and Arkansas from the rest of the Confederacy.

During the siege of Vicksburg, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston had gathered a force of 30,000 men in Jackson, Mississippi, with the intention of relieving the garrison under the command of John C. Pemberton that was trapped inside Vicksburg. After Pemberton surrendered to Grant on July 4, Johnston advanced towards the rear of Grant's forces. In response to this threat, Grant instructed Sherman to attack Johnston. Sherman conducted the ensuing Jackson Expedition, which concluded successfully on July 25 with the re-capture of the city of Jackson. This helped ensure that the Mississippi River would remain in Union hands for the remainder of the war. According to military historian Brian Holden-Reid, Sherman finally "had cut his teeth as an army commander" with the Jackson Expedition.[64]

Chattanooga

After the surrender of Vicksburg and the re-capture of Jackson, Sherman was given the rank of brigadier general in the regular army, in addition to his rank as a major general of volunteers. His family travelled from Ohio to visit him at the camp near Vicksburg. Sherman's nine-year-old son, Willie, the "Little Sergeant", tragically died from typhoid fever contracted during the trip.[65]

Following the defeat of the Army of the Cumberland at the Battle of Chickamauga by Confederate General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee, President Lincoln re-organized the Union forces in the West as the Military Division of the Mississippi, under the command of General Grant. Sherman succeeded Grant at the head of the Army of the Tennessee. Ordered to relieve the Union forces besieged in the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee, on October 11, 1863 Sherman departed from Memphis on a train bound for Chattanooga. When Sherman's train passed Collierville it came under attack by 3,000 Confederate cavalry and eight guns commanded by Brigadier General James Chalmers. Sherman took command of the infantrymen in the local Union garrison and successfully repelled the Confederate attack.[66]

Sherman proceeded to Chattanooga, where Grant instructed him to attack the right flank of Bragg's forces, which were entrenched along the Missionary Ridge. On November 25, Sherman took his assigned target of Billy Goat Hill at the north end of the ridge, only to find that it was separated from the main spine by a rock-strewn ravine. When he attempted to attack the main spine at Tunnel Hill, his troops were repeatedly repelled by Patrick Cleburne's heavy division, the best unit in Bragg's army. Grant then ordered George Henry Thomas to attack at the center of the Confederate line. This frontal assault was intended as a diversion, but it unexpectedly succeeded in capturing the enemy's entrenchments and routing the Confederate Army of Tennessee, bringing the Union's Chattanooga campaign to a successful completion.[67]

After Chattanooga, Sherman led a column to relieve Union forces under Ambrose Burnside thought to be in peril at Knoxville. In February 1864, he led an expedition to Meridian, Mississippi, to disrupt Confederate infrastructure.[68]

Atlanta

Despite this mixed record, Sherman enjoyed Grant's confidence and friendship. When Lincoln called Grant east in the spring of 1864 to take command of all the Union armies, Grant appointed Sherman (by then known to his soldiers as "Uncle Billy") to succeed him as head of the Military Division of the Mississippi, which entailed command of Union troops in the Western Theater of the war. As Grant took overall command of the armies of the United States, Sherman wrote to him outlining his strategy to bring the war to an end concluding that "if you can whip Lee and I can march to the Atlantic I think ol' Uncle Abe will give us twenty days leave to see the young folks."[69]

Sherman proceeded to invade the state of Georgia with three armies: the 60,000-strong Army of the Cumberland under George Henry Thomas, the 25,000-strong Army of the Tennessee under James B. McPherson, and the 13,000-strong Army of the Ohio under John M. Schofield.[70] He commanded a lengthy campaign of maneuver through mountainous terrain against Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, attempting a direct assault only at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. In July, the cautious Johnston was replaced by the more aggressive John Bell Hood, who played to Sherman's strength by challenging him to direct battles on open ground. Meanwhile, in August, Sherman "learned that I had been commissioned a major-general in the regular army, which was unexpected, and not desired until successful in the capture of Atlanta".[71]

Sherman's Atlanta campaign concluded successfully on September 2, 1864, with the capture of the city, which Hood had been forced to abandon. The fall of Atlanta had a major political impact in the North: it caused the collapse of the once powerful "Copperhead" faction within the Democratic Party, which had advocated immediate peace negotiations with the Confederacy. Sherman's military victory thus effectively ensured Abraham Lincoln's presidential re-election in November.[72]

After ordering almost all civilians to leave the city in September, Sherman gave instructions that all military and government buildings in Atlanta be burned, although many private homes and shops were burned as well.[73] This was to set a precedent for future behavior by his armies. The capture of the city of Atlanta made General Sherman a household name.

March to the Sea

During September and October, Sherman and Hood played cat-and-mouse in north Georgia (and Alabama) as Hood threatened Sherman's communications to the north. Eventually, Sherman won approval from his superiors for a plan to cut loose from his communications and march south, having advised Grant that he could "make Georgia howl".[74] This created the threat that Hood would move north into Tennessee. Trivializing that threat, Sherman reportedly said that he would "give [Hood] his rations" to go in that direction as "my business is down south".[75] However, Sherman left forces under Maj. Gens. George H. Thomas and John M. Schofield to deal with Hood; their forces eventually smashed Hood's army in the battles of Franklin (November 30) and Nashville (December 15–16).[76] Meanwhile, after the November elections, Sherman began a march on November 15[77] with 62,000 men to the port of Savannah, Georgia, living off the land and causing, by his own estimate, more than $100 million in property damage.[78] Sherman called this strategy "hard war". At the end of this campaign, known as Sherman's March to the Sea, his troops captured Savannah on December 21, 1864.[79] Sherman then dispatched a message to Lincoln, offering him the city as a Christmas present.[80]

Sherman's success in Georgia received ample coverage in the Northern press at a time when Grant seemed to be making little progress in his fight against Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. A bill was introduced in Congress to promote Sherman to Grant's rank of lieutenant general, probably with a view towards having him replace Grant as commander of the Union Army. Sherman wrote both to his brother, Senator John Sherman, and to General Grant vehemently repudiating any such promotion.[81] According to a war-time account,[82] it was around this time that Sherman made his memorable declaration of loyalty to Grant:

General Grant is a great general. I know him well. He stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk; and now, sir, we stand by each other always.

While in Savannah, Sherman learned from a newspaper that his infant son Charles Celestine had died during the Savannah campaign; the general had never seen the child.[83]

Final campaigns in the Carolinas

Grant then ordered Sherman to embark his army on steamers and join the Union forces confronting Lee in Virginia, but Sherman instead persuaded Grant to allow him to march north through the Carolinas, destroying everything of military value along the way, as he had done in Georgia. He was particularly interested in targeting South Carolina, the first state to secede from the Union, because of the effect that it would have on Southern morale.[84] His army proceeded north through South Carolina against light resistance from the troops of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. Upon hearing that Sherman's men were advancing on corduroy roads through the Salkehatchie swamps at a rate of a dozen miles per day, Johnston "made up his mind that there had been no such army in existence since the days of Julius Caesar".[85]

Sherman captured Columbia, the state capital, on February 17, 1865. Fires began that night and by next morning most of the central city was destroyed. The burning of Columbia has engendered controversy ever since, with some claiming the fires were a deliberate act of vengeance by the Union troops and others that the fires were accidental, caused in part by the burning bales of cotton that the retreating Confederates left behind them.[86]

Local Native American Lumbee guides helped Sherman's army cross the Lumber River, which was flooded by torrential rains, into North Carolina. According to Sherman, the trek across the Lumber River, and through the swamps, pocosins, and creeks of Robeson County was "the damnedest marching I ever saw".[87] Thereafter, his troops did little damage to the civilian infrastructure. North Carolina, unlike its southern neighbor, was regarded by the Union troops as a reluctant Confederate state, having been second from last to secede from the Union, ahead only of Tennessee. Sherman's final significant military engagement was a victory over Johnston's troops at the Battle of Bentonville, March 19–21. He soon rendezvoused at Goldsboro, North Carolina with Union troops awaiting him there after the capture of Fort Fisher and Wilmington.

In late March, Sherman briefly left his forces and traveled to City Point, Virginia, to confer with Grant. Lincoln happened to be at City Point at the same time, making possible the only three-way meeting of Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman during the war.[88] Also present at the City Point conference was Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter. This meeting was memorialized in G.P.A. Healy's painting The Peacemakers.[89]

Confederate surrender

Following Lee's surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House and the assassination of President Lincoln, Sherman met with Johnston on April 17, 1865 at Bennett Place in Durham, North Carolina, to negotiate a Confederate surrender. At the insistence of Johnston, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and Confederate Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge, Sherman conditionally agreed to generous terms that dealt with both military and political issues. On April 20, Sherman dispatched a memorandum with the proposed term to the government in Washington, D.C.[90]

Sherman believed that the generous terms that he had negotiated were consistent with the views that Lincoln had expressed at City Point, and that they were the best way to prevent Johnston from ordering his men to go into the wilderness and conduct a destructive guerrilla campaign. However, Sherman had proceeded without authority from General Grant, the newly installed President Andrew Johnson, or the Cabinet. The assassination of President Lincoln had caused the political climate in Washington, D.C. to turn against the prospect of a rapid reconciliation with the defeated Confederates, and the Johnson administration rejected Sherman's terms. General Grant may have had to intervene to save Sherman from dismissal for having overstepped his authority.[91] The US Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, leaked Sherman's memorandum to the New York Times, intimating that Sherman might have been bribed to allow Jefferson Davis to escape capture by the Union troops.[92] This precipitated a deep and long-lasting enmity between Sherman and Stanton, and it intensified Sherman's disdain for politicians.[93]

Grant offered Johnston purely military terms similar to those that he had negotiated with Lee at Appomattox. Johnston, ignoring instructions from President Davis, accepted those terms on April 26, 1865. He then formally surrendered his army and all the Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida in the largest single capitulation of the war.[94] Sherman proceeded with 60,000 of his troops to Washington, D.C., where they marched in the Grand Review of the Armies, on May 24, 1865, and were then disbanded. Having become the second most important general in the Union army, he thus had come full circle to the city where he started his war-time service as colonel of a non-existent infantry regiment.

Slavery and emancipation

Sherman was not an abolitionist before the war and, like others of his time and background, he did not believe in "Negro equality".[95][96] Before the war, Sherman at times even expressed some sympathy with the view of Southern whites that the black race was benefiting from slavery, although he opposed breaking up slave families and advocated teaching slaves to read and write.[97] During the Civil War, Sherman declined to employ black troops in his armies.[98]

Sherman's military campaigns of 1864 and 1865 freed many slaves, who greeted him "as a second Moses or Aaron"[95] and joined his marches through Georgia and the Carolinas by the tens of thousands. The fate of these refugees became a pressing military and political issue. Some abolitionists accused Sherman of doing little to alleviate the precarious living conditions of the freed slaves.[99] To address this issue, on January 12, 1865, Sherman met in Savannah with Secretary of War Stanton and with twenty local black leaders. After Sherman's departure, Garrison Frazier, a Baptist minister, declared in response to an inquiry about the feelings of the black community:

We looked upon General Sherman, prior to his arrival, as a man, in the providence of God, specially set apart to accomplish this work, and we unanimously felt inexpressible gratitude to him, looking upon him as a man that should be honored for the faithful performance of his duty. Some of us called upon him immediately upon his arrival, and it is probable he did not meet [Secretary Stanton] with more courtesy than he met us. His conduct and deportment toward us characterized him as a friend and a gentleman.[100]

Four days later, Sherman issued his Special Field Orders, No. 15. The orders provided for the settlement of 40,000 freed slaves and black refugees on land expropriated from white landowners in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Sherman appointed Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, an abolitionist from Massachusetts who had previously directed the recruitment of black soldiers, to implement that plan.[101] Those orders, which became the basis of the claim that the Union government had promised freed slaves "40 acres and a mule", were revoked later that year by President Andrew Johnson.

Although the context is often overlooked, and the quotation usually chopped off, one of Sherman's statements about his hard-war views arose in part from the racial attitudes summarized above. In his Memoirs, Sherman noted political pressures in 1864–1865 to encourage the escape of slaves, in part to avoid the possibility that "able-bodied slaves will be called into the military service of the rebels".[102] Sherman thought concentration on such policies would have delayed the "successful end" of the war and the "[liberation of] all slaves".[103] He went on to summarize vividly his hard-war philosophy and to add, in effect, that he really did not want the help of liberated slaves in subduing the South:

My aim then was to whip the rebels, to humble their pride, to follow them to their inmost recesses, and make them fear and dread us. "Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom." I did not want them to cast in our teeth what General Hood had once done at Atlanta, that we had to call on their slaves to help us to subdue them. But, as regards kindness to the race ..., I assert that no army ever did more for that race than the one I commanded at Savannah.[104]

Sherman's views on race evolved throughout his life. He dealt in a friendly and unaffected way with the black people that he met during his career, and in 1888, towards the end of his life, he published an essay in the North American Review defending the full civil rights of black citizens in the former Confederacy.[105]

Strategies

Sherman's record as a tactician was mixed, and his military legacy rests primarily on his command of logistics and on his brilliance as a strategist. The influential 20th-century British military historian and theorist B. H. Liddell Hart ranked Sherman as "the first modern general" and one of the most important strategists in the annals of war, along with Scipio Africanus, Belisarius, Napoleon Bonaparte, T. E. Lawrence, and Erwin Rommel.[106]

Maneuver warfare

Liddell Hart credited Sherman with mastery of maneuver warfare, also known as the "indirect approach". In maneuver warfare, a commander seeks to defeat the enemy on the battleground through shock, disruption, and surprise, while minimizing frontal attacks on well defended positions. According to Capt. Liddell Hart, this strategy was most clearly illustrated by Sherman's series of turning movements against Johnston during the Atlanta campaign. Liddell Hart also declared that the study of Sherman's campaigns had contributed significantly to his own "theory of strategy and tactics in mechanized warfare", which had in turn influenced Heinz Guderian's doctrine of Blitzkrieg and Rommel's use of tanks during the Second World War.[107] Another World War II-era student of Liddell Hart's writings about Sherman was General George S. Patton, who "'spent a long vacation studying Sherman's campaigns on the ground in Georgia and the Carolinas, with the aid of [Liddell Hart's] book'" and later "'carried out his [bold] plans, in super-Sherman style'".[108]

Hard war

Like Grant and Lincoln, Sherman was convinced that the Confederacy's strategic, economic, and psychological ability to wage further war needed to be definitively crushed if the fighting were to end. Therefore, he believed that the North had to conduct its campaign as a war of conquest, employing scorched earth tactics to break the backbone of the rebellion. He called this strategy "hard war". Sherman's advance through Georgia and the Carolinas was characterized by widespread destruction of civilian supplies and infrastructure. This strategy has been characterized by some military historians as an early form of total war, although the appropriateness of that term has been questioned by other scholars. Brian Holden-Reid, for instance, argued that "the concept of 'total war' is deeply flawed, an imprecise label that at best describes the two world wars but is of dubious relevance to the US Civil War."[109]

The damage done by Sherman marches through Georgia and the Carolinas was almost entirely limited to the destruction of property. Looting was officially forbidden, but historians disagree on how rigorously this regulation was enforced.[110] Though exact figures are not available, the loss of civilian life appears to have been very small.[111] Consuming supplies, wrecking infrastructure, and undermining morale were Sherman's stated goals, and several of his Southern contemporaries noted this and commented on it. For instance, Alabama-born Major Henry Hitchcock, who served in Sherman's staff, declared that "it is a terrible thing to consume and destroy the sustenance of thousands of people," but if the scorched earth strategy served "to paralyze their husbands and fathers who are fighting ... it is mercy in the end".[112]

The severity of the destructive acts by Union troops was significantly greater in South Carolina than in Georgia or North Carolina. This appears to have been a consequence of the animosity among both Union soldiers and officers to the state that they regarded as the "cockpit of secession".[113] One of the most serious accusations against Sherman was that he allowed his troops to burn the city of Columbia. In 1867, Gen. O. O. Howard, commander of Sherman's 15th Corps, reportedly said, "It is useless to deny that our troops burnt Columbia, for I saw them in the act."[114] However, Sherman himself stated that "[i]f I had made up my mind to burn Columbia I would have burnt it with no more feeling than I would a common prairie dog village; but I did not do it ..."[115] Sherman's official report on the burning placed the blame on Confederate Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton III, who Sherman said had ordered the burning of cotton in the streets. In his memoirs, Sherman said, "In my official report of this conflagration I distinctly charged it to General Wade Hampton, and confess I did so pointedly to shake the faith of his people in him, for he was in my opinion a braggart and professed to be the special champion of South Carolina."[116] Historian James M. McPherson has concluded that:

The fullest and most dispassionate study of this controversy blames all parties in varying proportions—including the Confederate authorities for the disorder that characterized the evacuation of Columbia, leaving thousands of cotton bales on the streets (some of them burning) and huge quantities of liquor undestroyed ... Sherman did not deliberately burn Columbia; a majority of Union soldiers, including the general himself, worked through the night to put out the fires.[117]

In this general connection, it is also noteworthy that Sherman and his subordinates (particularly John A. Logan) took steps to protect Raleigh, North Carolina, from acts of revenge after the assassination of President Lincoln.[118]

Modern assessment

After the fall of Atlanta in 1864, Sherman ordered the city's evacuation. When the city council appealed to him to rescind that order, on the grounds that it would cause great hardship to women, children, the elderly, and others who bore no responsibility for the conduct of the war, Sherman sent a written response in which he sought to articulate his conviction that a lasting peace would be possible only if the Union were restored, and that he was therefore prepared to do all he could do to quash the rebellion:

You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country. If the United States submits to a division now, it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal war ... I want peace, and believe it can only be reached through union and war, and I will ever conduct war with a view to perfect and early success. But, my dear sirs, when peace does come, you may call on me for anything. Then will I share with you the last cracker, and watch with you to shield your homes and families against danger from every quarter.[119]

Literary critic Edmund Wilson found in Sherman's Memoirs a fascinating and disturbing account of an "appetite for warfare" that "grows as it feeds on the South".[120] Former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara refers equivocally to the statement that "war is cruelty and you cannot refine it" in both the book Wilson's Ghost[121] and in his interview for the film The Fog of War.

But when comparing Sherman's scorched-earth campaigns to the actions of the British Army during the Second Boer War (1899–1902)—another war in which civilians were targeted because of their central role in sustaining a belligerent power—South African historian Hermann Giliomee claims that it "looks as if Sherman struck a better balance than the British commanders between severity and restraint in taking actions proportional to legitimate needs".[122] The admiration of scholars such as B. H. Liddell Hart, Lloyd Lewis, John F. Marszalek, Victor Davis Hanson, and Brian Holden-Reid for General Sherman owes much to what they see as an approach to the exigencies of modern armed conflict that was both effective and principled.

Postbellum service

In May 1865, after the major Confederate armies had surrendered, Sherman wrote in a personal letter:

I confess, without shame, I am sick and tired of fighting—its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentations of distant families, appealing to me for sons, husbands and fathers ... tis only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated ... that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation.[123]

In June 1865, two months after Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox, General Sherman received his first postwar command, originally called the Military Division of the Mississippi, later the Military Division of the Missouri, which came to comprise the territory between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Sherman's efforts in that position were focused on protecting the main wagon roads, such as the Oregon, Bozeman and Santa Fe Trails.[124] Tasked with guarding a vast territory with a limited force, Sherman was wary of the multitude of requests by territories and settlements for protection.[125] On July 25, 1866, Congress created the rank of General of the Army for Grant and then promoted Sherman to lieutenant general.

Indian Wars

There was little large-scale military action against the Indians during the first three years of Sherman's tenure as divisional commander, as Sherman was willing to let the process of negotiations play out in order to buy time to procure more troops and allow the completion of the Union Pacific and Kansas Pacific Railroads. During this time Sherman was a member of the Indian Peace Commission. Though the commission was responsible for the negotiation of the Medicine Lodge Treaty and the Treaty of Fort Laramie, Sherman did not play a significant role in the drafting of the treaties because in both cases he was called away to Washington during the negotiations.[126] In one instance, he was called to testify in the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson. However, Sherman was successful in negotiating other treaties, such as the removal of Navajos from the Bosque Redondo to traditional lands in Western New Mexico.[127] When the Medicine Lodge Treaty was broken in 1868, Sherman authorized his subordinate in Missouri, Philip Sheridan, to conduct the winter campaign of 1868–69, of which the Battle of Washita River was a part. Sheridan used hard-war tactics similar to those he and Sherman had employed in the Civil War. Sherman was also involved with the trial of Satanta and Big Tree: he ordered that the two chiefs should be tried as common criminals for their role in the Warren Wagon Train Raid, a raid in which Sherman himself came dangerously close to being killed.

One of Sherman's main concerns in postbellum service was to protect the construction and operation of the railroads from attack by hostile Indians. Sherman's views on Indian matters were often strongly expressed. He regarded the railroads "as the most important element now in progress to facilitate the military interests of our Frontier". Hence, in 1867, he wrote to Grant that "we are not going to let a few thieving, ragged Indians check and stop the progress of [the railroads]".[128] After the 1866 Fetterman Massacre, in which 81 US soldier were ambushed and killed by Native American warriors, Sherman wrote to Grant that "we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children...during an assault, the soldiers can not pause to distinguish between male and female, or even discriminate as to age".[129]

The displacement of Indians was facilitated by the growth of the railroads and the eradication of the buffalo. Sherman believed that the intentional eradication of the buffalo should be encouraged as a means of weakening Indian resistance to assimilation. He voiced this view in remarks to a joint session of the Texas legislature in 1875. However, he never engaged in any program to actually eradicate the buffalo.[130][131]

General of the Army

When U. S. Grant became president in 1869, Sherman was appointed Commanding General of the United States Army and promoted to the rank of full general. After the death of John A. Rawlins, Sherman also served for one month as interim Secretary of War.

Sherman's early tenure as Commanding General was marred by political difficulties, many of which stemmed from disagreements with Secretaries of War Rawlins and William W. Belknap, whom Sherman felt had usurped too much of the Commanding General's powers, reducing it to a sinecure.[125] Sherman also clashed with Eastern humanitarians who were critical of the Army's killing of Indians and who had apparently found an ally in President Grant.[125] To escape these difficulties, from 1874 to 1876, Sherman moved his headquarters to St. Louis, Missouri. He returned to Washington when the new Secretary of War, Alphonso Taft, promised him greater authority.[132]

Much of Sherman's time as Commanding General was devoted to making the Western and Plains states safe for settlement through the continuation of the Indian Wars, which included three significant campaigns: the Modoc War, the Great Sioux War of 1876, and the Nez Perce War. Despite his harsh treatment of the warring tribes, Sherman spoke out against the unfair way speculators and government agents treated the natives within the reservations.[133] During this time, Sherman reorganized the US Army forts to reflect the shifting frontier.[134]

In 1875, ten years after the end of the Civil War, Sherman became one of the first Civil War generals to publish his memoirs.[135] The Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. By Himself, published by D. Appleton & Co. in two volumes, began with the year 1846 (when the Mexican War began) and ended with a chapter about the "military lessons of the [civil] war". The publication of Sherman's memoirs sparked controversy and drew complaints from many quarters.[136] Grant, who was serving as US President when Sherman's memoirs appeared, later remarked that others had told him that Sherman treated Grant unfairly but "when I finished the book, I found I approved every word; that ... it was a true book, an honorable book, creditable to Sherman, just to his companions–to myself particularly so–just such a book as I expected Sherman would write."[137]

According to literary critic Edmund Wilson, Sherman:

[H]ad a trained gift of self-expression and was, as Mark Twain says, a master of narrative. [In his Memoirs] the vigorous account of his pre-war activities and his conduct of his military operations is varied in just the right proportion and to just the right degree of vivacity with anecdotes and personal experiences. We live through his campaigns ... in the company of Sherman himself. He tells us what he thought and what he felt, and he never strikes any attitudes or pretends to feel anything he does not feel.[138]

During the election of 1876, Southern Democrats who supported Wade Hampton for governor used mob violence to attack and intimidate African American voters in Charleston, South Carolina. Republican Governor Daniel Chamberlain appealed to President Grant for military assistance. In October 1876, Grant, after issuing a proclamation, instructed Sherman to gather all available Atlantic region troops and dispatch them to South Carolina to stop the mob violence.[139]

On June 19, 1879, Sherman delivered an address to the graduating class of the Michigan Military Academy, in which he may have uttered the famous phrase "War is Hell".[140] On April 11, 1880, he addressed a crowd of more than 10,000 in Columbus, Ohio: "There is many a boy here today who looks on war as all glory, but, boys, it is all hell."[141] In 1945, President Harry S. Truman would say: "Sherman was wrong. I'm telling you I find peace is hell."[142]

One of Sherman's significant contributions as head of the Army was the establishment of the Command School (now the Command and General Staff College) at Fort Leavenworth in 1881. Sherman stepped down as commanding general on November 1, 1883, and retired from the army on February 8, 1884.

Retirement

Sherman lived most of the rest of his life in New York City. He was devoted to the theater and to amateur painting and was much in demand as a colorful speaker at dinners and banquets, in which he indulged a fondness for quoting Shakespeare.[143] During this period, he stayed in contact with war veterans, and through them accepted honorary membership into the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity and the Irving Literary Society. In 1888 he joined the newly formed Boone and Crockett Club, a wildlife conservation organization founded by Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell.[144]

General Sherman was proposed as a Republican candidate for the presidential election of 1884, but he declined as emphatically as possible, saying, "I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected."[145] Such a categorical rejection of a candidacy is now referred to as a "Shermanesque statement".

In 1886, after the publication of Grant's memoirs, Sherman produced a "second edition, revised and corrected" of his own memoirs. The new edition, published by Appleton, added a second preface, a chapter about his life up to 1846, a chapter concerning the post-war period (ending with his 1884 retirement from the army), several appendices, portraits, improved maps, and an index. For the most part, Sherman refused to revise his original text on the ground that "I disclaim the character of historian, but assume to be a witness on the stand before the great tribunal of history" and "any witness who may disagree with me should publish his own version of [the] facts in the truthful narration of which he is interested". However, Sherman did add the appendices, in which he published the views of some others.[146] A "third edition, revised and corrected" of Sherman's memoirs was published in 1890 by Charles L. Webster & Co., the publisher of Grant's memoirs. This difficult to find edition was substantively identical to the second, except for the omission of Sherman's short 1875 and 1886 prefaces.[147]

Death

Sherman died of pneumonia in New York City at 1:50 PM on February 14, 1891, six days after his 71st birthday. President Benjamin Harrison sent a telegram to General Sherman's family and ordered all national flags to be flown at half mast. Harrison, in a message to the Senate and the House of Representatives, wrote that:

He was an ideal soldier, and shared to the fullest the esprit de corps of the army, but he cherished the civil institutions organized under the Constitution, and was only a soldier that these might be perpetuated in undiminished usefulness and honor.[148]

On February 19, a funeral service was held at his home, followed by a military procession. General Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate officer who had commanded the resistance to Sherman's troops in Georgia and the Carolinas, served as a pallbearer in New York City. It was a bitterly cold day and a friend of Johnston, fearing that the general might become ill, asked him to put on his hat. Johnston replied: "If I were in [Sherman's] place, and he were standing in mine, he would not put on his hat." Johnston did catch a serious cold and died one month later of pneumonia.[149]

General Sherman's body was then transported to St. Louis, where another service was conducted on February 21, 1891 at a local Catholic church. His son, Thomas Ewing Sherman, a Jesuit priest, presided over his father's funeral mass. Sherman is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.

Religious views

Sherman's birth family was Presbyterian and he was originally baptized as such. His foster family, including his future wife Ellen, were devout Catholics, and Sherman was re-baptized and later married in the Catholic rite. According to his son Thomas Ewing Sherman, who became a Catholic priest, Sherman attended the Catholic Church until the outbreak of the Civil War, but not thereafter.[150] In 1888, Sherman wrote publicly that "my immediate family are strongly Catholic. I am not and cannot be."[151] A memoirist reports that Sherman told him in 1887 that "my family is strongly Roman Catholic, but I am not."[152] Sherman wrote his wife Ellen Ewing in 1842 that "I believe in good works rather than faith."[153]

In his letters to Thomas, his eldest surviving son, General Sherman said "I don’t want you to be a soldier or a priest, but a good useful man",[154] and complained that Thomas's mother Ellen "thinks religion is so important that everything else must give way to it."[155] Thomas's decision to abandon his career as a lawyer in 1878 in order to join the Jesuits and prepare for the Catholic priesthood caused General Sherman profound distress, and he referred to it as a "great calamity". Father and son, however, were reconciled when Thomas returned to the United States in August 1880, after having travelled to England for his religious instruction.[156]

Monuments and tributes

The gilded bronze Sherman Memorial (1902) by Augustus Saint-Gaudens stands at the Grand Army Plaza near the main entrance to Central Park in New York City. The Sherman Monument (1903) by Carl Rohl-Smith stands near President's Park in Washington, D.C.[157] The Sherman Monument (1900) in Muskegon, Michigan features a bronze statue by John Massey Rhind, and the Sherman Monument (1903) in Arlington National Cemetery features a smaller version of Saint-Gaudens's equestrian statue. Copies of Saint-Gaudens's Bust of William Tecumseh Sherman are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and elsewhere.[158]

Other posthumous tributes to General Sherman include Sherman Circle in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, D.C., the naming of the World War II M4 Sherman tank,[159] and the "General Sherman" Giant Sequoia tree, which is the most massive documented single-trunk tree in the world.

Historiography

In the years immediately after the war, Sherman's conservative politics was attractive to many white Southerners. By the 1880s, however, Southern "Lost Cause" writers began to demonize Sherman for his attacks on civilians in Georgia and South Carolina. The magazine Confederate Veteran, based in Nashville, dedicated more attention to General Sherman than to any other figure, in part to enhance the visibility of the Civil War's Western Theater. In this discourse, Sherman's devastation of railroads and plantations mattered less than his insults to southern dignity and especially to its unprotected womanhood. By contrast, Sherman was popular in the North and well regarded by his own soldiers.[160]

In the early 20th century, Sherman's role the Civil War attracted the attention of several influential English military writers, including Field Marshal Lord Wolseley, Maj. Gen. J. F. C. Fuller, and especially Capt. B. H. Liddell Hart. The American historian Wesley Moody has argued that these English commentators tended to filter Sherman's actions and his hard-war strategy through their own ideas about modern warfare, thereby contributing to the exaggeration of his "atrocities" and unintentionally feeding into the negative assessment of Sherman's moral character associated with the "Lost Cause" school of US Southern historiography.[161] This led to the publication of several works, notably John B. Walters's Merchant of Terror: General Sherman and Total War (1973), which presented Sherman as responsible for "a mode of warfare which transgressed all ethical rules and showed an utter disregard for human rights and dignity."[162] Following Walters, James Reston Jr. argued in 1984 that Sherman had planted the "seed for the Agent Orange and Agent Blue programs of food deprivation in Vietnam".[163] More recently, historians such as Brian Holden-Reid have challenged such readings of Sherman's record and of his contributions to modern warfare.[164]

Dates of rank

| Insignia | Rank | Date | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Cadet, USMA | 1 July 1836 | Regular Army |

| Second Lieutenant | 1 July 1840 | Regular Army | |

| First Lieutenant | 30 November 1841 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Captain | 30 May 1848 | Regular Army | |

| Captain | 27 September 1850 | Regular Army (Resigned 6 September 1853.) | |

| Colonel | 14 May 1861 | Regular Army | |

| Brigadier General | 17 May 1861 | Volunteers | |

| Major General | 1 May 1862 | Volunteers | |

| Brigadier General | 4 July 1863 | Regular Army | |

| Major General | 12 August 1864 | Regular Army | |

| Lieutenant General | 25 July 1866 | Regular Army | |

| General | 4 March 1869 | Regular Army | |

| General | 8 February 1884 | Retired | |

| Source: [165] | |||

Writings

- General Sherman's Official Account of His Great March to Georgia and the Carolinas, from His Departure from Chattanooga to the Surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston and Confederate Forces under His Command (1865)

- "Autobiography, 1828–1861" (c. 1868), Mss. 57, WTS Papers, Ohio Historical Society. Private recollections for Sherman's children.

- Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Written by Himself (1875), 2d ed. with additional chapters (1886)

- Reports of Inspection Made in the Summer of 1877 by Generals P. H. Sheridan and W. T. Sherman of Country North of the Union Pacific Railroad (co-author, 1878)

- The Sherman Letters: Correspondence between General and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891 (posthumous, 1894)

- Home Letters of General Sherman (posthumous, 1909)

- General W. T. Sherman as College President: A Collection of Letters, Documents, and Other Material, Chiefly from Private Sources, Relating to the Life and Activities of General William Tecumseh Sherman, to the Early Years of Louisiana State University, and the Stirring Conditions Existing in the South on the Eve of the Civil War (posthumous, 1912)

- The William Tecumseh Sherman Family Letters (posthumous, 1967). Microfilm collection prepared by the Archives of the University of Notre Dame contains letters, etc. from Sherman, his wife, and others.

- Sherman at War (posthumous, 1992)

- Sherman's Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860–1865 (posthumous, 1999)

See also

Notes

- ^ 1864, 1865

- ^ One historian has written that Sherman's "genius" for "strategy and logistics ... made him one of the foremost architects of Union victory". Steven E. Woodworth, Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 631. For a very critical study of Sherman, see John B. Walters, Merchant of Terror: General Sherman and Total War (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1973).

- ^ Liddell Hart, p. 430.

- ^ See, William T. Sherman papers, Notre Dame University CSHR 19/67 Folder:Roger Sherman's Watch 1932–1942

- ^ McDonough, William Tecumseh Sherman: in the service of my country, A Life, pp. 148–149

- ^ One 19th-century source, for example, states that "General Sherman, we believe, is the only eminent American named from an Indian chief". Howe's Historical Collections of Ohio (Columbus, 1890), I:595.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 11.

- ^ Lewis, p. 34.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 11; Lewis, p. 23; Schenker, "'My Father ... Named Me William Tecumseh': Rebutting the Charge That General Sherman Lied About His Name", Ohio History (2008), vol. 115, p. 55; Sherman biographer John Marszalek considers the cited article to "present a convincing case regarding Sherman's name". Marszalek, "Preface" to 2007 edition of Sherman: A Soldier's Passion for Order, pp. xiv–xv n.1.

- ^ See, e.g., the many Civil War letters reproduced in Brooks D. Simpson and Jean V. Berlin, Sherman's Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1999).

- ^ See, for instance, Walsh, p. 32.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 14

- ^ Hirshson, p. 13

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 16

- ^ Hirshson, p. 21

- ^ Sherman at the Virtual Museum of San Francisco Archived May 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine and excerpts from Sherman's Memoirs Archived February 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Survey Report: Raised Streets & Hollow Sidewalks, Sacramento, California" (PDF). City of Sacramento. July 20, 2009. p. 7. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Kevin Dougherty, Civil War Leadership and Mexican War Experience, (Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 2007), pp. 96–100. ISBN 1-57806-968-8

- ^ Katherine Burton, Three Generations: Maria Boyle Ewing – Ellen Ewing Sherman – Minnie Sherman Fitch (Longmans, Green & Co., 1947), pp. 72–78.

- ^ Edward Sorin, CSC, The Chronicles of Notre Dame Du Lac ed. James T. Connelly, CSC (Notre Dame: Notre Dame Press, 1992), 289.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 125–129.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 131–134, 166.

- ^ Quoted in Royster, pp. 133–134

- ^ Memoirs, chronology, p. 1093.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 150–161. For details about Sherman's banking career, see Dwight L. Clarke, William Tecumseh Sherman: Gold Rush Banker (San Francisco: California Historical Society, 1969).

- ^ "Department of Military Science: Unit History". LSU Army ROTC. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 160–162.

- ^ See History of LSU. Archived March 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quoted in Hirshson, p. 68.

- ^ Walters, John B. (1973). Merchant of Terror: General Sherman and Total War. Bobbs-Merrill. p. 9. ISBN 978-0672517822.

- ^ Lloyd Lewis (1993) [1932]. Sherman: Fighting Prophet. U of Nebraska Press. p. 138. ISBN 0803279450. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ Exchange between W.T. Sherman and Prof. David F. Boyd, December 24, 1860. Quoted in "Sherman: Fighting Prophet" (1932) by Lloyd Lewis, page 138, attributed to "Boyd (D.F), mss. [manuscripts] in possession of Walter L. Fleming, Nashville, Tenn." Fleming's collection is now in the archives of Louisiana State University.

- ^ Letter by W.T. Sherman to Gov. Thomas O. Moore, January 18, 1861. Quoted in Sherman, Memoirs, p. 156.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 184–186; see Marszalek, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 186–189.

- ^ Samuel M. Bowman and Richard B. Irwin, Sherman and His Campaigns (New York, 1865), 25.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 189–190; Hirshson, pp. 83–86.

- ^ WTS to Thomas Ewing Jr., June 3, 1861, in Sherman and Berlin 97–98.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 200.

- ^ Miller, p. 67

- ^ Holden Reid, p. 96

- ^ Holden Reid, p. 97

- ^ Hirshson, pp. 90–94, 109.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 210, 216

- ^ For more detailed discussion of this overall period, see Marszalek, Sherman, pp. 154–167; Hirshson, White Tecumseh, pp. 95–105; Kennett, Sherman, pp. 127–149.

- ^ Sherman to George B. McClellan, November 4, 1861, in Stephen W. Sears, ed., The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1861–1865 (New York, 1989), p. 127, note 1; Marszalek, Sherman, pp. 161–164.

- ^ Lewis, p. 203.

- ^ Sherman to John Sherman, January 4, 8, 1862, in Simpson and Berlin, Sherman's Civil War, 174, 176.

- ^ Cincinnati Commercial, December 11, 1861; Marszalek, Sherman, pp. 162, 164.

- ^ Kennett, pp. 155–156

- ^ WTS to USG, February 15, 1862, Papers of Ulysses S. Grant 4:216n; Smith, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eicher, p. 485

- ^ Daniel, p. 138

- ^ Quoted in Walsh, pp. 77–78

- ^ Smith, Grant, p. 212: Schenker, "Ulysses in His Tent," passim.

- ^ Marszalek, Sherman, pp. 188–201.

- ^ John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 176

- ^ See Marszalek, Sherman, pp. 202–208. Sherman's operations were supposed to be coordinated with an advance on Vicksburg by Grant from another direction. Unbeknownst to Sherman, Grant abandoned his advance. "As a result, [Sherman's] river expedition ran into more than they bargained for." Smith, Grant, p. 224.

- ^ Smith, p. 227.

- ^ See Marszalek, pp. 208–210; Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 318–325.

- ^ Smith, pp. 235–236

- ^ Daniel, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Whitelaw Reid, Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers (New York, 1868), 1:387.

- ^ Holden Reid, p. 205

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 370–375.

- ^ Holden Reid, p. 218

- ^ McPherson, pp. 677–680.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 406–434; Buck T. Foster, Sherman's Meridian Campaign (University of Alabama Press, 2006).

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 589

- ^ McPherson, p. 653

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 576. The nomination was not submitted to the Senate until December. Eicher, p. 702.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (2008). Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 231–250.

- ^ Russell S. Bonds, War Like the Thunderbolt: The Battle and Burning of Atlanta (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2009), 337–74.

- ^ Telegram W.T. Sherman to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, October 9, 1864, reproduced in Sherman's Civil War, p. 731.

- ^ Faunt Le Roy Senour, Major General William T. Sherman, and His Campaigns (Chicago, 1865), 293; see also Hirshson, White Tecumseh, pp. 246–247, 431 n.23.

- ^ W.T. Sherman to Gen. U.S. Grant, November 1, 1864, reproduced in Sherman's Civil War, pp. 746–747.

- ^ Trudeau, p. 76

- ^ Report by Maj. Gen. W.T. Sherman, January 1, 1865, quoted in Grimsley, p. 200

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 693.

- ^ This message was put on a vessel on December 22, passed on by telegram from Fort Monroe, Virginia, and apparently received by Lincoln on Christmas Day itself. Sherman, Memoirs, p. 711; Official Records, Series I, vol. 44, 783; New York Times, December 26, 1864 Archived February 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See, for instance, Liddell Hart, p. 354

- ^ Brockett, p. 175 (p. 162 in 1865 edition).

- ^ Marszalek, Sherman, p. 311.

- ^ John F. Marszalek, "'Take the Seat of Honor': William T. Sherman," in Steven E. Woodworth, ed., Grant's Lieutenants: From Chattanooga to Appomattox (Lawrence: Univ. of Kansas Press, 2008), pp. 5, 17–18; Marszalek, Sherman, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Jacob D. Cox, Military Reminiscences of the Civil War (1900), vol. 2, 531–32; Jacob D. Cox, The March to the Sea (1882), p. 168; Johnston is also quoted in McPherson, p. 828.

- ^ Marszalek, pp. 322–325.

- ^ Lewis, p. 513.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 806-17; Donald C. Pfanz, The Petersburg Campaign: Abraham Lincoln at City Point (Lynchburg, VA, 1989), 1-2, 24-29, 94-95.

- ^ The Peacemakers at the Wayback Machine (archived September 27, 2011)

- ^ Holden Reid, pp. 403–404

- ^ Holden Reid, pp. 404

- ^ Holden Reid, pp. 405

- ^ Holden Reid, pp. 414–415

- ^ See, for instance, Johnston's Surrender at Bennett Place on Hillsboro Road Archived January 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sherman, William Tecumseh (May 10, 1999). "Letter to Salmon P. Chase, January 11, 1865". In Simpson, Brooks D.; Berlin, Jean V. (eds.). Sherman's Civil War. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 794–95. ISBN 9780807824405.

- ^ B. H. Liddell Hart (1929). "Letter by W.T. Sherman to John Sherman, August 1865". Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co. p. 406.

- ^ Bassett, Thom (January 17, 2012). "Sherman's Southern Sympathies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ Sherman to Halleck, September 4, 1864, Civil War Official Records Vol. 38 part 5, pp. 792–793.

- ^ See, for instance, Sherman, Memoirs, vol. II, p. 247.

- ^ "Sherman meets the colored ministers in Savannah". Civilwarhome.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- ^ Special Field Orders, No. 15 Archived December 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, January 16, 1865. See also McPherson, pp. 737–739

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 728–729, quoting a December 30, 1864 letter from Henry W. Halleck.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 729.

- ^ Sherman, Memoirs, 2d ed., ch. XXII, p. 729 (Lib. of America, 1990).

- ^ Holden Reid, pp. 8, 505–507

- ^ Liddell Hart, p. 430

- ^ Liddell Hart, foreword to the Indiana University Press's edition of Sherman's Memoirs (1957). Quoted in Wilson, p. 179

- ^ Hirshson, p. 393, quoting B. H. Liddell Hart, "Notes on Two Discussions with Patton, 1944", February 20, 1948, GSP Papers, box 6, USMA Library

- ^ Holden Reid, p. 500

- ^ See, for instance, Grimsley, pp. 190–204; McPherson, pp. 712–714, 727–729.

- ^ See, for instance, Grimsley, p. 199

- ^ Hitchcock, p. 125

- ^ See, for instance, Grimsley, pp. 200–202.