Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

| Impeachment of Andrew Johnson | |

|---|---|

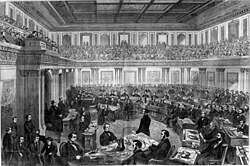

Theodore R. Davis's illustration of President Johnson's impeachment trial in the Senate, published in Harper's Weekly | |

| Accused | Andrew Johnson, President of the United States |

| Date | February 24, 1868 to May 26, 1868 |

| Outcome | Acquitted by the U.S. Senate, remained in office |

| Charges | Eleven high crimes and misdemeanors |

| Cause | Violating the Tenure of Office Act by attempting to replace Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, while Congress was not in session and other abuses of presidential power |

| Congressional votes | |

| Voting in the U.S. House of Representatives | |

| Accusation | High crimes and misdemeanors |

| Votes in favor | 126 |

| Votes against | 47 |

| Result | Approved resolution of impeachment |

| Voting in the U.S. Senate | |

| Accusation | Articles II and III |

| Votes in favor | 35 "guilty" |

| Votes against | 19 "not guilty" |

| Result | Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) |

| Accusation | Article XI |

| Votes in favor | 35 "guilty" |

| Votes against | 19 "not guilty" |

| Result | Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) |

| The Senate held a roll call vote on only 3 of the 11 articles before adjourning as a court. | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

15th Governor of Tennessee

16th Vice President of the United States

17th President of the United States

Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

|

||

The impeachment of Andrew Johnson was initiated on February 24, 1868, when the United States House of Representatives resolved to impeach Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, for "high crimes and misdemeanors", which were detailed in 11 articles of impeachment. The primary charge against Johnson was that he had violated the Tenure of Office Act, passed by Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto. Specifically, he had removed from office Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war whom the act was largely designed to protect. Stanton often sided with the Radical Republican faction that passed the act, and Stanton did not have a good relationship with Johnson. Johnson attempted to replace Stanton with Brevet Major General Lorenzo Thomas. Earlier, while the Congress was not in session, Johnson had suspended Stanton and appointed General Ulysses S. Grant as secretary of war ad interim.

Johnson became the first American president to be impeached on March 2–3, 1868, when the House formally adopted the articles of impeachment and forwarded them to the United States Senate for adjudication. The trial in the Senate began three days later, with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding. On May 16, the Senate did not convict Johnson on one of the articles, with the 35–19 vote in favor of conviction falling one vote short of the necessary two-thirds majority. A 10-day recess was called before attempting to convict him on additional articles. On May 26, the Senate did not convict the president on two articles, both by the same margin, after which the trial was adjourned without considering the remaining eight articles of impeachment.

The impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson had important political implications for the balance of federal legislative-executive power. It maintained the principle that Congress should not remove the president from office simply because its members disagreed with him over policy, style, and administration of the office. It also resulted in diminished presidential influence on public policy and overall governing power, fostering a system of governance which future-President Woodrow Wilson referred to in the 1880s as "Congressional Government".[1]

Background[]

Presidential Reconstruction[]

Tensions between the executive and legislative branches had been high prior to Johnson's ascension to the presidency. Following Union Army victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July 1863, President Lincoln began contemplating the issue of how to bring the South back into the Union. He wished to offer an olive branch to the rebel states by pursuing a lenient plan for their reintegration. The forgiving tone of the president's plan, plus the fact that he implemented it by presidential directive without consulting Congress, incensed Radical Republicans, who countered with a more stringent plan. Their proposal for Southern reconstruction, the Wade–Davis Bill, passed both houses of Congress in July 1864, but was pocket vetoed by the president and never took effect.[2][3]

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, just days after the Army of Northern Virginia's surrender at Appomattox, briefly lessened the tension over who would set the terms of peace. The radicals, while suspicious of the new president (Andrew Johnson) and his policies, believed based on his record that he would defer or at least acquiesce to their hardline proposals. Though a Democrat from Tennessee, Johnson had been a fierce critic of the Southern secession. Then after several states left the Union, including his own, he chose to stay in Washington (rather than resign his U.S. Senate seat), and later, when Union troops occupied Tennessee, Johnson was appointed military governor. While in that position he had exercised his powers with vigor, frequently stating that "treason must be made odious and traitors punished".[3] Johnson, however, embraced Lincoln's more lenient policies, thus rejecting the Radicals, and setting the stage for a showdown between the president and Congress.[4] During the first months of his presidency, Johnson issued proclamations of general amnesty for most former Confederates, both government and military officers, and oversaw creation of new governments in the hitherto rebellious states—governments dominated by ex-Confederate officials.[5] In February 1866, Johnson vetoed legislation extending the Freedmen's Bureau and expanding its powers; Congress was unable to override the veto. Afterward, Johnson denounced Radical Republicans Representative Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner, along with abolitionist Wendell Phillips, as traitors.[6] Later, Johnson vetoed a Civil Rights Act and a second Freedmen's Bureau bill. The Senate and the House each mustered the two-thirds majorities necessary to override both vetoes,[6] setting the stage for a showdown between Congress and the president.

At an impasse with Congress, Johnson offered himself directly to the American public as a "tribune of the people". In the late summer of 1866, the president embarked on a national "Swing Around the Circle" speaking tour, where he asked his audiences for their support in his battle against the Congress and urged voters to elect representatives to Congress in the upcoming midterm election who supported his policies. The tour backfired on Johnson, however, when reports of his undisciplined, vitriolic speeches and ill-advised confrontations with hecklers swept the nation. Contrary to his hopes, the 1866 elections led to veto-proof Republican majorities in both houses of Congress.[1][7][8] As a result, Radicals were able to take control of Reconstruction, passing a series of Reconstruction Acts—each one over the president's veto—addressing requirements for Southern states to be fully restored to the Union. The first of these acts divided those states, excluding Johnson's home state of Tennessee, into five military districts, and each state's government was put under the control of the U.S. military. Additionally, these states were required to enact new constitutions, ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, and guarantee voting rights for black males.[1][3][9]

Previous efforts to impeach Johnson[]

Since 1866, a number of previous efforts had been undertaken to impeach Johnson. On January 7, 1867, this resulted in the House of Representatives voting to launch of an impeachment inquiry run by the House Committee on the Judiciary, which initially ended in a June 3, 1867 vote by the committee to recommend against forwarding articles of impeachment to the full House.[10] however, on November 25, 1867, the House Committee on the Judiciary, which had not previously forwarded the result of its inquiry to the full House, reversed their previous decision, and voted 5–4 to recommend impeachment proceedings. In a December 7, 1867 vote, the full House rejected this report’s recommendation by a 108–56 vote.[11][12][13]

Tenure of Office Act[]

Congress' control of the military Reconstruction policy was mitigated by Johnson's command of the military as president. However, Johnson had inherited Lincoln's appointee Edwin M. Stanton as secretary of war. Stanton was a staunch Radical Republican who would comply with congressional Reconstruction policies as long as he remained in office.[14] To ensure that Stanton would not be replaced, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867 over Johnson's veto. The act required the president to seek the Senate's advice and consent before relieving or dismissing any member of his cabinet (an indirect reference to Stanton) or, indeed, any federal official whose initial appointment had previously required its advice and consent.[15][16]

Because the Tenure of Office Act did permit the president to suspend such officials when Congress was out of session, when Johnson failed to obtain Stanton's resignation, he instead suspended Stanton on August 5, 1867, which gave him the opportunity to appoint General Ulysses S. Grant, then serving as Commanding General of the Army, interim secretary of war.[17] When the Senate adopted a resolution of non-concurrence with Stanton's dismissal in December 1867, Grant told Johnson he was going to resign, fearing punitive legal action. Johnson assured Grant that he would assume all responsibility in the matter, and asked him to delay his resignation until a suitable replacement could be found.[16] Contrary to Johnson's belief that Grant had agreed to remain in office,[18] when the Senate voted and reinstated Stanton in January 1868, Grant immediately resigned, before the president had an opportunity to appoint a replacement.[19] Johnson was furious at Grant, accusing him of lying during a stormy cabinet meeting. The March 1868 publication of several angry messages between Johnson and Grant led to a complete break between the two. As a result of these letters, Grant solidified his standing as the front-runner for the 1868 Republican presidential nomination.[17][20]

Johnson complained about Stanton's restoration to office and searched desperately for someone to replace Stanton who would be acceptable to the Senate. He first proposed the position to General William Tecumseh Sherman, an enemy of Stanton, who turned down his offer.[21] Sherman subsequently suggested to Johnson that Radical Republicans and moderate Republicans would be amenable to replacing Stanton with Jacob Dolson Cox, but he found the president to be no longer interested in appeasement.[22] On February 21, 1868, the president appointed Lorenzo Thomas, a brevet major general in the Army, as interim Secretary of War. Johnson thereupon informed the Senate of his decision. Thomas personally delivered the president's dismissal notice to Stanton, who rejected the legitimacy of the decision. Rather than vacate his office, Stanton barricaded himself inside and ordered Thomas arrested for violating the Tenure of Office Act. He also informed Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax and President Pro Tempore of the Senate Benjamin Wade of the situation.[23] Thomas remained under arrest for several days before being released, and having the charge against him dropped after Stanton realized that the case against Thomas would provide the courts with an opportunity to review the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act.[24]

Johnson's opponents in Congress were outraged by his actions; the president's challenge to congressional authority—with regard to both the Tenure of Office Act and post-war reconstruction—had, in their estimation, been tolerated for long enough.[3] In swift response, an impeachment resolution was introduced in the House by Representatives Thaddeus Stevens and John Bingham. Expressing the widespread sentiment among House Republicans, Representative William D. Kelley (on February 22, 1868) declared:

Sir, the bloody and untilled fields of the ten unreconstructed states, the unsheeted ghosts of the two thousand murdered negroes in Texas, cry, if the dead ever evoke vengeance, for the punishment of Andrew Johnson.[25][26]

Inquiry[]

On January 22, 1868, Rufus P. Spalding moved that the rules be suspended so that he could present a resolution resolving,

that the Committee on Reconstruction be authorized to inquire what combinations have been made or attempted to be made to obstruct the due execution of the laws, and to that end the committee have power to send for persons and papers and to examine witnesses on oath, and report to this House what action, if any, they may deem necessary, and that said committee have leave to report at any time.[27]

This motion was agreed to by a vote of 103–37, and then, after several subsequent motions (including ones to table the resolution or adjourn) were disagreed to, congress voted to approve the resolution 99–31.[27] This launched a new inquiry into Johnson run by the Committee on Reconstruction.[27]

Also on January 22, 1868, a one sentence resolution to impeach Johnson, written by John Covode, was also referred to the Committee on Reconstruction. The resolution read, "Resolved, that Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors."[28][29][30]

On February 21, the day that Johnson attempted to replace Stanton with Lorenzo Thomas, Thaddeus Stevens submitted a resolution resolving that the evidence taken on impeachment by the previous impeachment inquiry run by the Committee on the Judiciary be referred to the Committee on Reconstruction, and that the committee "have leave to report at any time" was approved by the House.[27] On February 22, Stevens presented from the Committee on Reconstruction a report opining that Johnson should be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors.[27]

Impeachment[]

On February 24, 1868, three days after Johnson's dismissal of Stanton, the House of Representatives voted 126 to 47 (with 17 members not voting) in favor of a resolution to impeach the president for high crimes and misdemeanors. Thaddeus Stevens addressed the House prior to the vote. "This is not to be the temporary triumph of a political party", he said, "but is to endure in its consequence until this whole continent shall be filled with a free and untrammeled people or shall be a nest of shrinking, cowardly slaves."[25] Almost all Republicans present supported impeachment, while every Democrat present voted against it. (Samuel Fenton Cary, an Independent Republican from Ohio, and Thomas E. Stewart, a Conservative Republican from New York, voted against impeachment.)[31]

| Resolution providing for the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| February 24, 1868 | Party | Total votes[32][31] | |

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yea |

0 | 126 | 126 |

| Nay | 45 | 2 | 47 |

One week later, the House adopted 11 articles of impeachment against the president. The articles alleged that Johnson had:[33]

Trial[]

Officers of the trial[]

Top row L-R: Butler, Stevens, Williams, Bingham; bottom row L-R: Wilson, Boutwell, Logan

Per the constitution's rules on impeachment trials of incumbent presidents, chief justice of the United States Salmon P. Chase presided over the trial.[16]

The House of Representatives appointed seven members to serve as House impeachment managers, equivalent to prosecutors. These seven members were John Bingham, George S. Boutwell, Benjamin Butler, John A. Logan, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams and James F. Wilson.[34][35]

The president's defense team was made up of Henry Stanbery, William M. Evarts, Benjamin R. Curtis, Thomas A. R. Nelson and William S. Groesbeck. On the advice of counsel, the president did not appear at the trial.[16]

Pretrial[]

On March 4, 1868, amid tremendous public attention and press coverage, the 11 Articles of Impeachment were presented to the Senate, which reconvened the following day as a court of impeachment, with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding, and proceeded to develop a set of rules for the trial and its officers.[16] The extent of Chase's authority as presiding officer to render unilateral rulings was a frequent point of contention during the rules debate and trial. He initially maintained that deciding certain procedural questions on his own was his prerogative; but after the Senate challenged several of his rulings, he gave up making rulings.[36] On one occasion, when he ruled that Johnson should be permitted to present evidence that Thomas' appointment to replace Stanton was intended to provide a test case to challenge the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate reversed the ruling.[37]

When it came time for senators to take the juror's oath, Thomas A. Hendricks questioned Benjamin Wade's impartiality and suggested that Wade abstain from voting due to a conflict of interest. As there was no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vacancy in the vice presidency (accomplished a century later by the Twenty-fifth Amendment), the office had been vacant since Johnson succeeded to the presidency. Therefore, Wade, as president pro tempore of the Senate, would, under the Presidential Succession Act then in force and effect, become president if Johnson were removed from office. Reviled by the Radical Republican majority, Hendricks withdrew his objection a day later and left the matter to Wade's own conscience; he subsequently voted for conviction.[38][39]

The trial was conducted mostly in open session, and the Senate chamber galleries were filled to capacity throughout. Public interest was so great that the Senate issued admission passes for the first time in its history. For each day of the trial, 1,000 color coded tickets were printed, granting admittance for a single day.[16][40]

Testimony[]

On the first day, Johnson's defense committee asked for 40 days to collect evidence and witnesses since the prosecution had had a longer amount of time to do so, but only 10 days were granted. The proceedings began on March 23. Senator Garrett Davis argued that because not all states were represented in the Senate the trial could not be held and that it should therefore be adjourned. The motion was voted down. After the charges against the president were made, Henry Stanbery asked for another 30 days to assemble evidence and summon witnesses, saying that in the 10 days previously granted there had only been enough time to prepare the president's reply. John A. Logan argued that the trial should begin immediately and that Stanbery was only trying to stall for time. The request was turned down in a vote 41 to 12. However, the Senate voted the next day to give the defense six more days to prepare evidence, which was accepted.[41]

The trial commenced again on March 30. Benjamin Butler opened for the prosecution with a three-hour speech reviewing historical impeachment trials, dating from King John of England. For days Butler spoke out against Johnson's violations of the Tenure of Office Act and further charged that the president had issued orders directly to Army officers without sending them through General Grant. The defense argued that Johnson had not violated the Tenure of Office Act because President Lincoln did not reappoint Stanton as Secretary of War at the beginning of his second term in 1865 and that he was, therefore, a leftover appointment from the 1860 cabinet, which removed his protection by the Tenure of Office Act. The prosecution called several witnesses in the course of the proceedings until April 9, when they rested their case.[42]

Benjamin Curtis called attention to the fact that after the House passed the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate had amended it, meaning that it had to return it to a Senate-House conference committee to resolve the differences. He followed up by quoting the minutes of those meetings, which revealed that while the House members made no notes about the fact, their sole purpose was to keep Stanton in office, and the Senate had disagreed. The defense then called their first witness, Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. He did not provide adequate information in the defense's cause and Butler made attempts to use his information to the prosecution's advantage. The next witness was General William T. Sherman, who testified that President Johnson had offered to appoint Sherman to succeed Stanton as secretary of war in order to ensure that the department was effectively administered. This testimony damaged the prosecution, which expected Sherman to testify that Johnson offered to appoint Sherman for the purpose of obstructing the operation or overthrow, of the government. Sherman essentially affirmed that Johnson only wanted him to manage the department and not to execute directions to the military that would be contrary to the will of Congress.[43]

Verdict[]

The Senate was composed of 54 members representing 27 states (10 former Confederate states had not yet been readmitted to representation in the Senate) at the time of the trial. At its conclusion, senators voted on three of the articles of impeachment. On each occasion the vote was 35–19, with 35 senators voting guilty and 19 not guilty. As the constitutional threshold for a conviction in an impeachment trial is a two-thirds majority guilty vote, 36 votes in this instance, Johnson was not convicted. He remained in office through the end of his term on March 4, 1869, though as a lame duck without influence on public policy.[1]

Seven Republican senators were concerned that the proceedings had been manipulated to give a one-sided presentation of the evidence. Senators William P. Fessenden, Joseph S. Fowler, James W. Grimes, John B. Henderson, Lyman Trumbull, Peter G. Van Winkle,[44] and Edmund G. Ross, who provided the decisive vote,[45] defied their party by voting against conviction. In addition to the aforementioned seven, three more Republicans James Dixon, James Rood Doolittle, Daniel Sheldon Norton, and all nine Democratic senators voted not guilty.

The first vote was taken on May 16 for the eleventh article. Prior to the vote, Samuel Pomeroy, the senior senator from Kansas, told the junior Kansas Senator Ross that if Ross voted for acquittal that Ross would become the subject of an investigation for bribery.[46] Afterward, in hopes of persuading at least one senator who voted not guilty to change his vote, the Senate adjourned for 10 days before continuing voting on the other articles. During the hiatus, under Butler's leadership, the House put through a resolution to investigate alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate". Despite the Radical Republican leadership's heavy-handed efforts to change the outcome, when votes were cast on May 26 for the second and third articles, the results were the same as the first. After the trial, Butler conducted hearings on the widespread reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson's acquittal. In Butler's hearings, and in subsequent inquiries, there was increasing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of patronage jobs and cash bribes. Political deals were struck as well. Grimes received assurances that acquittal would not be followed by presidential reprisals; Johnson agreed to enforce the Reconstruction Acts, and to appoint General John Schofield to succeed Stanton. Nonetheless, the investigations never resulted in charges, much less convictions, against anyone.[47]

Moreover, there is evidence that the prosecution attempted to bribe the senators voting for acquittal to switch their votes to conviction. Maine Senator Fessenden was offered the ministership to Great Britain. Prosecutor Butler said, "Tell [Kansas Senator Ross] that if he wants money there is a bushel of it here to be had."[48] Butler's investigation also boomeranged when it was discovered that Kansas Senator Pomeroy, who voted for conviction, had written a letter to Johnson's postmaster general seeking a $40,000 bribe for Pomeroy's acquittal vote along with three or four others in his caucus.[49] Butler was himself told by Wade that Wade would appoint Butler as secretary of state when Wade assumed the presidency after a Johnson conviction.[50] An opinion that Senator Ross was mercilessly persecuted for his courageous vote to sustain the independence of the presidency as a branch of the federal government is the subject of an entire chapter in President John F. Kennedy's book, Profiles in Courage.[51] That opinion has been rejected by some scholars, such as Ralph Roske, and endorsed by others, such as Avery Craven.[52][53]

Not one of the Republican senators who voted for acquittal ever again served in an elected office.[54] Although they were under intense pressure to change their votes to conviction during the trial, afterward public opinion rapidly shifted around to their viewpoint. Some senators who voted for conviction, such as John Sherman and even Charles Sumner, later changed their minds.[52][55][56]

| Articles of Impeachment, U.S. Senate judgment (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 16, 1868 Article XI |

Party | Total votes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democratic | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nay (not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 26, 1868 Article II |

Party | Total votes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democratic | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nay (not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 26, 1868 Article III |

Party | Total votes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democratic | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nay (Not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Later review of Johnson's impeachment[]

In 1887, the Tenure of Office Act was repealed by Congress, and subsequent rulings by the United States Supreme Court seemed to support Johnson's position that he was entitled to fire Stanton without congressional approval. The Supreme Court's ruling on a similar piece of later legislation in Myers v. United States (1926) affirmed the ability of the president to remove a postmaster without congressional approval, and stated in its majority opinion "that the Tenure of Office Act of 1867...was invalid".[59]

Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, one of the 10 Republican senators whose refusal to vote for conviction prevented Johnson's removal from office, noted, in the speech he gave explaining his vote for acquittal, that had Johnson been convicted, the main source of the president's political power—the freedom to disagree with the Congress without consequences—would have been destroyed, and the Constitution's system of checks and balances along with it:[60]

Once set the example of impeaching a President for what, when the excitement of the hour shall have subsided, will be regarded as insufficient causes, as several of those now alleged against the President were decided to be by the House of Representatives only a few months since, and no future President will be safe who happens to differ with a majority of the House and two thirds of the Senate on any measure deemed by them important, particularly if of a political character. Blinded by partisan zeal, with such an example before them, they will not scruple to remove out of the way any obstacle to the accomplishment of their purposes, and what then becomes of the checks and balances of the Constitution, so carefully devised and so vital to its perpetuity? They are all gone.

See also[]

- Impeachment process against Richard Nixon

- Impeachment of Bill Clinton

- First impeachment of Donald Trump

- Second impeachment of Donald Trump

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- Tennessee Johnson, a 1942 film about Andrew Johnson, depicting the events surrounding his impeachment

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Varon, Elizabeth R. "Andrew Johnson: Domestic Affairs". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Burlingame, Michael. "Abraham Lincoln: Domestic Affairs". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Whittington, Keith E. (March 2000). "Bill Clinton Was No Andrew Johnson: Comparing Two Impeachments" (PDF). Journal of Constitutional Law. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. 2 (2): 422–65. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Campbell, James M.; Fraser, Rebecca J., eds. (2008). Reconstruction: People and Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. xv. ISBN 978-1-59884-021-6. Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- ^ Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 193–213. ISBN 978-0-393-31742-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Andrew Johnson – Key Events". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 234–54. ISBN 978-0-393-31742-8.

- ^ Kennedy, David M.; Bailey, Thomas (2009). The American Spirit: U.S. History as Seen by Contemporaries, Volume II: Since 1865 (Twelfth ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-495-80002-6.

- ^ Hacker, Jeffrey H. (2014). Slavery, War, and a New Birth of Freedom: 1840s–1877 (revised ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7656-8324-3. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ "Building the Case for Impeachment, December 1866 to June 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment Efforts Against President Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment Rejected, November to December 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "The Case for Impeachment, December 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. p. 594. ISBN 978-1-5942-0487-6.

- ^ Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 275–99. ISBN 978-0-393-31742-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (1868) President of the United States". Washington, D.C.: Historical Office, United States Senate. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burg, Robert (2012). Manweller, Mathew (ed.). Chronology of the U.S. Presidency [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 545. ISBN 978-1-59884-645-4. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House Publishing Group. p. 453. ISBN 978-1-5883-6992-5.

- ^ Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. p. 603. ISBN 978-1-5942-0487-6.

- ^ White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 454–55. ISBN 978-1-5883-6992-5.

- ^ Marvel, William (2015). Lincoln's Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton. University of North Carolina Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-1-46962249-1. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ Benedict, Michael Les (Fall 1998). "A New Look at the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson". Political Science Quarterly. Academy of Political Science. 113 (3). doi:10.2307/2658078. JSTOR 2658078. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-393-31742-8.

- ^ Marvel, William (2015). Lincoln's Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton. University of North Carolina Press. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-46962249-1. Archived from the original on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Glass, Andrew (February 24, 2015). "House votes to impeach Andrew Johnson, February 24, 1868". politico.com. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Brockett, L. P. (1872). Men of our day; or, Biographical sketches of patriots, orators, statesmen, generals, reformers, financiers and merchants, now on the stage of action: including those who in military, political, business and social life, are the prominent leaders of the time in this country. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Zeigler, McCurdy. p. 502 – via Internet Archive, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hinds, Asher C. (4 March 1907). "HINDS' PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES INCLUDING REFERENCES TO PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION, THE LAWS, AND DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE" (PDF). United States Congress. pp. 845–846. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Avalon Project : History of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson - Chapter VI. Impeachment Agreed To By The House". avalon.law.yale.edu. The Avalon Project (Yale Law School Lilian Goldman Law Library). Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "The House Impeaches Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment of Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The House Impeaches Andrew Johnson". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2nd Sess. 1400 (1868)". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document: Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2019.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document: Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "List of Individuals Impeached by the House of Representatives". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "President Andrew Johnson Impeachment Trial: 1868 - Senate Tries President Johnson". law.jrank.org. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Gerhardt, Michael J. "Essays on Article I: Trial of Impeachment". Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Herrick, Neal Q. (2009). After Patrick Henry: A Second American Revolution. New York City: Black Rose Books. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-55164-320-5.

- ^ Hearn, Chester G. (2000). The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0863-4.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. HarperCollins. p. 336. ISBN 978-0062035868.

- ^ "President Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial, 1868". Washington, D.C.: Historical Office, United States Senate. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives; Ninety-third Congress, Second Session (1974). Impeachment: Selected Materials on Procedure. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 104–05. OCLC 868888.

- ^ Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon and Schuster. pp. 207–12. ISBN 978-1416547495.

- ^ Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon and Schuster. p. 231.

- ^ "Andrew Johnson Trial: The Consciences of Seven Republicans Save Johnson" Archived 2018-08-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ ""The Trial of Andrew Johnson, 1868"". Archived from the original on 2018-08-10. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ Curt Anders "Powerlust: Radicalism in the Civil War Era" p. 531

- ^ Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon and Schuster. pp. 240–49, 284–99.

- ^ Gene Davis High Crimes and Misdemeanors (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1977), 266–67, 290–91

- ^ Curt Anders "Powerlust: Radicalism in the Civil War Era", pp. 532–33

- ^ Eric McKitrick Andrew Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 507–08

- ^ John F. Kennedy "Profiles in Courage" (New York: Harper Brothers, 1961), 115–39

- ^ Jump up to: a b Avery Craven "Reconstruction" (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1969), 221

- ^ Roske, Ralph J. (1959). "The Seven Martyrs?". The American Historical Review. 64 (2): 323–30. doi:10.2307/1845447. JSTOR 1845447.

- ^ Hodding Carter, The Angry Scar (New York: Doubleday, 1959), 143

- ^ Kenneth Stampp, Reconstruction (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965), 153

- ^ Chester Hearn, The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000), 202

- ^ Ross, Edmund G. (1896). History of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson, President of The United States By The House Of Representatives and His Trial by The Senate for High Crimes and Misdemeanors in Office 1868 (PDF). pp. 105–07. Retrieved April 26, 2018 – via Project Gutenberg, 2000.

- ^ "Senate Journal. 40th Cong., 2nd sess., 16 / 26 May 1868, 943–51". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ Myers v. United States Archived 2014-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Findlaw | Cases and Codes

- ^ White, Horace. The Life of Lyman Trumble. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1913, p. 319.

Further reading[]

- Benedict, Michael Les. "A New Look at the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson", Political Science Quarterly, Sep 1973, Vol. 88 Issue 3, pp. 349–67 in JSTOR

- Benedict, Michael Les. The impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson (1973), 212 pp; the standard scholarly history online edition

- Brown, H. Lowell. High Crimes and Misdemeanors in Presidential Impeachment (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010). pp. 35–61 on Johnson.

- DeWitt, David M. The impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson (1903), old monograph online edition

- Hearn, Chester G. The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (2000) popular history

- McKitrick, Eric L. Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1960) influential analysis

- Rable, George C. "Forces of Darkness, Forces of Light: The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson and the Paranoid Style", Southern Studies (1978) 17#2, pp. 151–73

- Sefton, James E. "The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson: A Century of Writing", Civil War History, June 1968, Vol. 14 Issue 2, pp. 120–47

- Sigelman, Lee, Christopher J. Deering, and Burdett A. Loomis. "'Wading Knee Deep in Words, Words, Words': Senatorial Rhetoric in the Johnson and Clinton Impeachment Trials". Congress & the Presidency 28#2 (2001) pp. 119–39.

- Stathis, Stephen W. "Impeachment and Trial of President Andrew Johnson: A View from the Iowa Congressional Delegation", Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 24, No. 1, (Winter, 1994), pp. 29–47 in JSTOR

- Stewart, David O. Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (2009)

- Trefousse, Hans L. "The Acquittal of Andrew Johnson and the Decline of the Radicals", Civil War History, June 1968, Vol. 14 Issue 2, pp. 148–61

- Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989) major scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Trefousse, Hans L. Impeachment of a President: Andrew Johnson, the Blacks, and Reconstruction (1999)

- Wineapple, Brenda (2019). The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0812998368.

External links[]

- Andrew Johnson Impeachment Trial (1868), essay and other resources, www.famous-trials.com, University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School

- The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson, excerpts from 1865–1869 Harper's Weekly articles along with other information (a HarpWeek website)

- Interview with William Rehnquist on Grand Inquests: The Historic Impeachments of Justice Samuel Chase and President Andrew Johnson, 1992, Booknotes, C-SPAN

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- 19th-century American trials

- Trials of political people