Waite Court

| Waite Court | |

|---|---|

| |

| March 4, 1874 – March 23, 1888 (14 years, 19 days) | |

| Seat | Old Senate Chamber Washington, D.C. |

| No. of positions | 9 |

| Waite Court decisions | |

| |

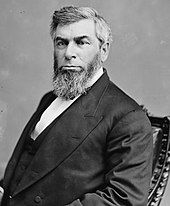

The Waite Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1874 to 1888, when Morrison Waite served as the seventh Chief Justice of the United States. Waite succeeded Salmon P. Chase as Chief Justice after the latter's death. Waite served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Melville Fuller was nominated and confirmed as Waite's successor.

The Waite Court presided over the end of the Reconstruction Era, and the start of the Gilded Age. It also played an important role during the constitutional crisis that arose following the 1876 presidential election, as five of its members served on the Electoral Commission that Congress created to settle the dispute over who won the Electoral College vote.

During the Waite's tenure, the jurisdiction of federal circuit courts (as against that of the State courts) was expanded by the Jurisdiction and Removal Act of 1875, which gave the federal judiciary full jurisdiction over federal questions. As a result of the change, caseloads in the federal courts grew considerably.

Membership[]

The Waite court began with the appointment of Morrison Waite by President Ulysses S. Grant to succeed Chief Justice Salmon Chase. Grant had previously nominated Attorney General George Henry Williams and former Attorney General Caleb Cushing, but withdrew both nominations after encountering opposition in the Senate. The Waite Court began with eight holdovers from the Chase Court: Nathan Clifford, Noah Haynes Swayne, Samuel Freeman Miller, David Davis, Stephen Johnson Field, William Strong, Joseph P. Bradley, and Ward Hunt. Clifford, Miller, Field, Strong, and Bradley served on the 1877 Electoral Commission.

Davis resigned from the court in 1877 to serve in the United States Senate, and President Rutherford B. Hayes successfully nominated John Marshall Harlan to replace him. In 1880, Hayes successfully nominated William Burnham Woods to replace the retiring Strong. In 1881, President James Garfield nominated Stanley Matthews to replace the retiring Swayne. President Chester A. Arthur added Horace Gray and Samuel Blatchford to the court, replacing Clifford and Hunt. Woods died in 1887, and President Grover Cleveland appointed Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II to the court.

Timeline[]

Other branches[]

Presidents during this court included Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, and Grover Cleveland. Congresses during this court included 43rd through the 50th United States Congresses.

Rulings of the Court[]

Notable rulings of the Waite Court include:

- United States v. Reese (1875): In a 7–2 decision delivered by Chief Justice Waite, the court held that the Fifteenth Amendment does not prevent states from using ostensibly race-neutral limitations on voting rights such as poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests. The decision played a major role in allowing states to effectively disenfranchise African-Americans.

- Minor v. Happersett (1875): In a unanimous decision written by Chief Justice Waite, the court held that the Constitution did not grant women the right to vote. The ruling was effectively overturned by the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

- United States v. Cruikshank (1875): In a 9–0 decision delivered by Chief Justice Waite, the court overturned indictments arising from the Colfax massacre. The court held that the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause only apply to state action, and that the Fourteenth Amendment had not incorporated the First or Second amendments to apply to the states. The decision was a major blow to the power of the Enforcement Acts and the federal government's ability to protect the rights of African-Americans in the South. Later decisions, including Gitlow v. New York (1925), would incorporate most of the Bill of Rights to apply to states.

- Reynolds v. United States (1878): In a decision delivered by Chief Justice Waite, the court upheld the conviction of George Reynolds. Reynolds, a member of the LDS Church, had been convicted of bigamy under the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act. The court held that the banning of bigamy did not conflict with the Establishment Clause.

- Pennoyer v. Neff (1878): In a decision written by Justice Field, the court held that a state can exert personal jurisdiction over a defendant if the defendant is served notice while physically present in a state.

- Strauder v. West Virginia (1880): In a 7–2 decision delivered by Justice Strong, the court held that the Equal Protection Clause bans exclusionary policies that lead to all-white juries. The decision overturned the conviction of Taylor Strauder, an African-American convicted of murder in West Virginia by an all-white jury. Strauder was the first time that the Court reversed a state criminal conviction for a violation of a constitutional provision concerning criminal procedure.[1]

- Pace v. Alabama (1883): In a unanimous decision delivered by Justice Field, the court upheld Alabama's anti-miscegenation laws. Pace was later overruled by Loving v. Virginia (1967) on the basis of the Equal Protection Clause.

- The Civil Rights Cases (1883): In an 8–1 decision delivered by Justice Bradley, the court struck down part of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, holding that the Equal Protection Clause and the Thirteenth Amendment do not protect against racial discrimination by private actors. The decision has not been overturned, and most future legislation against private discrimination (such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964) was passed on the basis of the Commerce Clause.

- Elk v. Wilkins (1884): In a 7–2 decision delivered by Justice Gray, the court held that the Citizenship Clause does not automatically grant citizenship to Native Americans born on Indian reservations. The case was effectively overruled by the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924.

- The Railroad Commission Cases (1886): In a 6-2 decision delivered by Chief Justice Waite, the court upheld state fixation of railroad prices as a permissible exercise of police power. Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway Co. v. Minnesota (1890) later limited the effect of this ruling.

- Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway Co. v. Illinois (1886):

- Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Co. (1886):

- Presser v. Illinois (1886): In a decision delivered by Justice Woods, the court affirmed its decision in Cruikshank, saying that the First and Second Amendments do not apply to state governments. The decision overturned the conviction of Herman Presser, a member of Lehr und Wehr Verein, a Chicago-based socialist military organization.

- The Telephone Cases (1888): In a series of court cases related to the invention of the telephone, the court upheld Alexander Graham Bell's patents against the claims of Western Union. The court split, 4–3, on the ruling, and Chief Justice Waite delivered the majority opinion.

Judicial philosophy[]

The Waite Court confronted constitutional questions arising from the Civil War, Reconstruction, the expansion of the federal government following the Civil War, and the emergence of a national economy linked together by railroads.[2] The Waite Court issued several major decisions, including Cruikshank, that denied the federal government the power to protect the civil rights of African Americans.[3] However, historian Michael Les Benedict notes that the civil rights decision were made during the era of dual federalism, and the Waite Court was sincerely concerned with maintaining the balance of power between the federal government and state governments.[4] While the Waite Court struck down civil rights laws, it upheld many economic regulations, in contrast with the Fuller Court.[5]

References[]

- ^ Michael J. Klarman, The Racial Origins of Modern Criminal Procedure, 99 Mich. L. Rev. 48 (2000).

- ^ Stephenson, D. Grier (2003). The Waite Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. pp. xi–xiii. ISBN 9781576078297. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Davis, Abraham L. (25 July 1995). The Supreme Court, Race, and Civil Rights: From Marshall to Rehnquist. SAGE Publications. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9781452263793. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Benedict, Michael Les (1978). "Preserving Federalism: Reconstruction and the Waite Court". The Supreme Court Review. 1978: 41–44. doi:10.1086/scr.1978.3109529. JSTOR 3109529. S2CID 147451330.

- ^ Benedict, Michael Les (2011). "New Perspectives on the Waite Court". Tulsa Law Review. 47 (1): 112–113. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

Further reading[]

- Abraham, Henry Julian (2008). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742558953.

- Beth, Loren P. (2015). John Marshall Harlan: The Last Whig Justice. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813149851.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. (1995). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Goldstone, Lawrence (2011). Inherently Unequal: The Betrayal of Equal Rights by the Supreme Court, 1865-1903. Walker Books. ISBN 978-0802717924.

- Hall, Kermit L.; Ely, Jr., James W.; Grossman, Joel B., eds. (2005). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176612.

- Hall, Kermit L.; Ely, Jr., James W., eds. (2009). The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195379396.

- Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438108179.

- Hoffer, Peter Charles; Hoffer, WilliamJames Hull; Hull, N. E. H. (2018). The Supreme Court: An Essential History (2nd ed.). University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2681-6.

- Howard, John R. (1999). The Shifting Wind: The Supreme Court and Civil Rights from Reconstruction to Brown. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791440896.

- Irons, Peter (2006). A People's History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped Our Constitution (Revised ed.). Penguin. ISBN 9781101503133.

- Kens, Paul (1997). Justice Stephen Field: Shaping Liberty from the Gold Rush to the Gilded Age. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700608171.

- Kens, Paul (2012). The Supreme Court under Morrison R. Waite, 1874-1888. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781611172195.

- Lane, Charles (2008). The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9781429936781.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Pope, James Gray (Spring 2014). "Snubbed landmark: Why United States v. Cruikshank (1876) belongs at the heart of the American constitutional canon". Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. Harvard Law School. 49 (2): 385–447. Pdf

- Ross, Michael A. (2003). Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court during the Civil War Era. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807129241.

- Schwarz, Bernard (1995). A History of the Supreme Court. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195093872.

- Stephenson, D. Grier (2003). The Waite Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078297.

- Tomlins, Christopher, ed. (2005). The United States Supreme Court: The Pursuit of Justice. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0618329694.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- White, Richard (2017). The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age: 1865–1896. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190619060.

- Yarbrough, Tinsley E. (1995). Judicial Enigma: the First Justice Harlan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195074642.

- Waite Court

- 1880s in the United States

- United States Supreme Court history by court