Wings Over Jordan Choir

Wings Over Jordan Choir | |

|---|---|

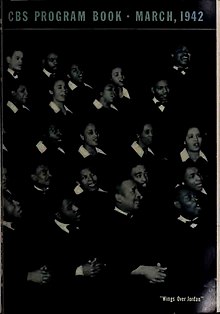

1939 publicity photo of the Wings Over Jordan Choir. The Rev. Glenn Thomas Settle is standing at front right, with "WGAR" and "CBS" microphones on opposite ends of the choir. | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | The Negro Hour Choir |

| Origin | Cleveland, Ohio, United States |

| Genres | Spirituals |

| Instruments | A capella |

| Years active | 1935–1978[a] |

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts |

|

| Past members | See § Personnel |

| Other names | The Negro Hour |

|---|---|

| Genre | Spirituals |

| Running time | 25 minutes |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Language(s) | English |

| Home station | WGAR, Cleveland, Ohio |

| Syndicates |

|

| Starring | Wings Over Jordan Choir |

| Announcer | Wayne Mack (all WGAR-produced episodes)[2] |

| Created by | |

| Recording studio | Hotel Statler (WGAR main studio);[5] various CBS and Mutual affiliates[6][7] |

| Other studios | Euclid Avenue Baptist Church, Cleveland, Ohio (summer of 1941)[8] |

| Original release | July 11, 1937 – December 25, 1949[c] |

| No. of episodes |

|

| Audio format | Monaural sound |

| Opening theme | "Go Down Moses"[9] |

| Sponsored by |

|

The Wings Over Jordan Choir was an African-American a cappella spiritual choir, founded and based in Cleveland, Ohio. This choir is also known for a weekly religious radio series, also titled Wings Over Jordan, that was created as a showcase for the group.

Debuting over Cleveland radio station WGAR in 1937 as the Negro Hour, the radio program was broadcast over the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) from 1938 to 1947 and over the Mutual Broadcasting System through 1949. Wings Over Jordan broke color barriers as the first radio program produced and hosted by African-Americans to be nationally broadcast over a network. This program was also the first of its kind to be easily accessible to audiences in the Deep South, featuring distinguished black church and civic leaders, scholars and artists as guest speakers. One of the highest-rated religious radio programs in the United States, this show additionally had an international audience via the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the Voice of America (VOA), Armed Forces Radio, and their respective shortwave capacities. The radio program has also been credited for both WGAR and CBS winning inaugural Peabody Awards in 1941.

Founded in Cleveland by Baptist minister Glynn Thomas Settle (born Glenn Thomas Settle;[b] October 10, 1894 – July 16, 1967), the choir performed in concerts throughout the country during their pinnacle, often in defiance of Jim Crow laws, and toured with the USO in support of the American war effort during both World War II and the Korean War. Billed as one of the "world's greatest Negro choirs", Wings Over Jordan Choir is regarded as a forerunner[10] for the civil rights movement[11] and a driving force in the development of choral music,[12] helping to both preserve[13] and introduce traditional spirituals to a mainstream audience.[14] Multiple iterations of the group emerged from the 1950s onward, and a Cleveland-based tribute choir bearing this name has actively performed since 1988.

History[]

1935–1938: Formations[]

Origins in Cleveland[]

Members of the "Wings Over Jordan" choir, prior to the organization of the group, were mainly members of the Gethsemane Church choir. Few of the vocalists have had any formal musical training. Men in the group were house painters, garage attendants, chauffeurs, WPA workers and elevator operators, while women were employed as maids, cooks and seamstresses.

The Call and Post, April 12, 1941[15]

Wings Over Jordan had its origins as a church choir at Gethsemane Baptist Church in Cleveland's Central neighborhood under the direction of the Rev. Glenn Thomas Settle.[16] Born in Reidsville, North Carolina, on October 10, 1894, to sharecroppers Ruben and Mary B. Settle[17] as one of nine children, Settle's paternal grandfather Tom Settle was an African prince captured and sold into slavery in the 1850s, while his maternal grandfather had been a member of the Cherokee Nation.[18] The Settle family moved to Uniontown, Pennsylvania, in 1902, where Glenn became involved in local churches[19] and worked as many as three jobs following his father's death.[20] Moving to Cleveland in 1917 with his first wife Mary Elizabeth Carter,[21][20] Settle studied at the Moody Bible Institute after being inspired to become better educated, taking classes in the evening while working as a metallurgist[21] in a foundry during the day.[22] Prior to his ordination, Settle headed a church in Painesville[21] and was assigned to a Baptist church in Elyria that split into two congregations[23] in 1933.[24] While in Elyria, Settle became known for sermons that helped promoted easing of racial tensions and social justice advocacy.[25] Settle then was assigned as Gethsemane's pastor in November 1935 as the church was in the middle of a significant fiscal crisis, successfully leading a turnaround to a "very healthy" financial state.[22] In addition to heading up Gethsemane, Settle worked as a clerk for Cleveland's street department.[26]

Like Settle, the majority of Gethsemane's congregation consisted of migrant families from the South, and was not one of the city's more prominent churches, but did boast a choir of rich and natural, yet untrained, voices.[27] These singers had humble backgrounds: they consisted of laborers, maids, beauticians and elevator operators, among other professions.[28][15] As Gethsemane had no music ministry,[18] Settle promptly established an a cappella choir with these singers, along with singers from other choirs[29] and from Cleveland's Central High School, where much of the congregation had attended.[30] James E. Tate, who had become involved with Gethsemane when Settle was appointed pastor, was appointed as director.[31] The choir's repertoire of spirituals documented the psychology of African-Americans throughout their enslavement in the United States, and while falling out of favor among blacks after emancipation, experienced a resurgence in popularity with the Great Depression's onset.[32] Settle saw spirituals as a dignified art form and sought to preserve their authenticity with the choir; consequently, performances often held a deeply emotional atmosphere, a reflection of Settle's work as a minister.[33] While regarded as "sorrow songs",[32] spirituals also held hope for a better future among blacks,[29] and choir members felt comfort and relief in singing their ancestor's songs[34] helping them overcome feelings of hopelessness.[35] Settle's granddaughter Teretha Settle Overton later compared spirituals to gospel songs, saying the former are songs of woe while the latter proclaim salvation and redemption.[16] The choir quickly became popular in Cleveland with concert bookings throughout the city[36] and even embarked on a regional tour early in 1937 that included Settle's hometown of Uniontown.[37]

The WGAR Negro Hour[]

After consulting a colleague in Cleveland's street department that was also an ethnic radio broadcaster, Settle enrolled the choir into an on-air amateur contest hosted by Cleveland station WJAY.[d] The choir was ruled ineligible as the station considered them professional artists, but Worth Kramer, program director for WGAR radio, was in the audience, unbeknownst to Settle.[26] Following the WJAY audition and learning of Worth Kramer's position,[40] Rev. Settle approached him[41] with a request to add a weekly show aimed at the African-American population to WGAR's existing Sunday lineup of ethnic fare.[11] A network affiliate of NBC Blue,[e] WGAR recently removed a Sunday morning Blue program featuring the Southernaires from their schedule after a local nationality group purchased the timeslot,[43] and despite an array of programming for other European-based ethnic groups, had nothing for Cleveland's black population.[11] Kramer was impressed[41] by a subsequent audition held for the choir[30] that he promptly launched the Negro Hour on July 11, 1937,[22] which Settle's choir provided music for.[44]

In addition to the choir's music performances, the Negro Hour boasted guest speakers who would talk about issues facing black people; the debut program's guests were the Rev. H. C. Bailey and Cleveland mayor Harold Hitz Burton.[43] Not only was the Negro Hour the first known radio program autonomously produced and directed by African-Americans, it is also regarded as the first program of any kind to feature black people in a way that wasn't demeaning or burlesque.[45] Kramer became an early supporter of the choir after having developed a personal interest in spirituals and researched their origins, and considered it to be "the only true form of early American music".[46] Settle and the choir—now known as the Negro Hour Choir[47]—were featured performers at the Ohio Baptist General Association's 1937 conference, which WGAR broadcast live.[48] James E. Tate was also bestowed $450 by Gethsemane's congregation for his planned studies at Oberlin College, Settle having praised Tate for a "natural ability ... to train and direct singing groups".[31]

Going national via CBS[]

My only knowledge of Dr. Suttle (sic) is derived from his relation to (Wings Over Jordan). I am thoroughly convinced, however, that he is a man of sound intelligence, deep seated piety and of earnest consecration and devotion to the welfare of his race. His conduct of the Sunday morning program is characterized by a reverent and devout spirit which is deeper than the requirement of a broadcast program... Of all the Sunday morning broadcast which bombarded the throne of Heaven, none are more intense with spiritual meaning, and power than those conveyed in the jubilee melodies, which sprung out of the soul of unsophisticated black folk.

Kelly Miller, New York Age, June 25, 1938[49]

On September 26, 1937, WGAR switched affiliations from NBC Blue to the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS).[42] The sudden success of WGAR's Negro Hour quickly caught the attention of CBS, in particular network executive director Sterling Fisher[41] and musical director Davidson Taylor.[22] A special 15-minute prime time slot was awarded to the choir by the network on Tuesday, November 9, 1937.[50] Entitled Wings Over Jordan, the program featured a performance of the Robert Nathaniel Dett piece "Keep Me From Sinking Down".[51] Another prime time slot was granted to the choir by CBS on December 14, 1937, allowing network executives another chance to hear the choir with the potential of offering a regularly scheduled feature.[52] Nashville religious leader Henry Allen Boyd appeared on the December 5, 1937, Negro Hour, marking the first time an individual outside of Cleveland was a guest speaker.[53] CBS officially picked up the program, officially re-titled Wings Over Jordan, for national distribution on January 9, 1938.[22][10] What was already the first program independently produced and hosted by African-Americans now became the first such program to be broadcast nationwide over a radio network.[13]

The choir concurrently adopted "Wings Over Jordan" as their permanent name onward.[16] While the origins of this name are directly attributed to Rev. Settle, he never offered or provided an exact meaning for its creation, rendering it an enigma.[54] A Newsweek article later explained its meaning as a reference to the African-American Christian cultural belief of crossing the River Jordan upon one's death and hearing the "winged chorus of angels" while completing the journey to the afterlife.[55] Settle's administrative assistant Alice Harper McCrady speculated it emerged from his penchant of using analogies in sermons with "Wings Over Jordan" as a metaphor; many spirituals regarded wings as representative of "flying away" from slavery, and both "The River of Jordan" and "Deep River" were frequently performed by the choir.[56] One newspaper article promoting a 1949 concert asserts that Settle adopted the phrase from lyrics to a song that had been sung by his mother.[57] Another theory suggests that Settle simply thought the phrase "had a nice ring to it" when CBS used it for the two prime time programs.[56] In any event, the name proceeded to serve both Settle and the choir for the next 30 years.[58]

1938–1942: Widespread popularity[]

Worth Kramer's direction[]

When the program went national, Settle replaced James E. Tate as the choir's director with WGAR's Worth Kramer, who was white.[11] Settle initially said Kramer's role would be for a period of four weeks citing his prior experience with chorales,[47] but Kramer remained in the position for several additional weeks, prompting Tate to resign the following month.[59][60] While Tate was offered—and had accepted—his former position back after significant discontent expressed by other members,[59] Tate permanently left the choir one month later.[61] The director position was consequently given to Kramer outright, with Tate's former assistant Williette Firmbanks becoming a secondary director,[62] including road performances that Kramer could not attend.[55] Kramer left his position as WGAR program director in 1939 to head an "artists service" department established by the station, allowing him to devote more attention to the choir.[63] Ultimately, Kramer's four week period as Wings choir director lasted four years,[55] helping to set a standard with his knowledge of radio production and musical sensitivities that subsequent conductors all emulated.[64]

Choral groups have always been my hobby, and I saw in this group an opportunity to preserve America's finest contribution to the music world—the Negro spiritual.

Worth Kramer[65]

Despite Settle's insistence no one, even Kramer, would be taking undue credit for the choir's success,[47] Kramer received disproportionate credit in media coverage and concert promotions[66][67] which was controversial among the members.[11] A 1940 Time profile on the program claimed Kramer "drummed his arrangements into the musically illiterate group by rote... for weeks before he put them on the air".[68] While Kramer, sometimes in collaboration with Firmbanks,[61] did compose multiple arrangements for the choir, it was to help compliment the many members who could not read sheet music proficiently.[69] Kramer publicly defended the choir in a 1941 open letter to multiple swing band leaders demanding they refrain from appropriating spirituals for their purposes.[55] In the letter, Kramer said, "to many of the opposite race, (this) is exceedingly distasteful. Imagine your disgust, in tuning in a late evening dance program, to hear... the blatant strains of a band "jiving" "All Hail the Power of Jesus' Name" or "The Old Rugged Cross"... you would run immediately to the telephone to protect such irreverent expression of musical prowess".[70] Historians and family of surviving choir members have retrospectively seen Kramer as helping them gain legitimacy and the pickup over Columbia; Teretha Overton said of Kramer, "(he) opened doors that my grandfather could not get in".[11] Even still, some CBS affiliates in the Deep South, including Shreveport, Louisiana's KWKH, advertised the show as "Wings Over Jordan ... the Worth Kramer Choir."[71]

Extensive concert tours[]

Wings Over Jordan became CBS's highest-profile sustaining program, with the network agreeing to cover all costs for the airtime allotted to the show, negating the need for any commercial sponsorship.[69] While it was estimated that the program had an audience of ten million listeners every week[72] and was billed as one of the most-listened to religious radio programs,[44] sustained programs were not officially rated like sponsored programs were, and thus no definitive measurements exist.[73] Still, it was not uncommon for predominantly black neighborhoods in Cleveland to have the majority of radios tuned in to WGAR[11] with radios placed on porches or open windows, broadcasting the program for all to hear.[16] The summer of 1938 also saw the first significant concert tour for the choir, including cities in Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama, with Settle making arrangements for choir members to stay in the homes of black families if the organizations hosting them could not provide lodging.[74] Settle refused to let the choir perform to segregated audiences, resulting in the choir being occasionally jailed for violating Jim Crow laws, prompting them to broadcast from historically black colleges and universities.[12] Worth Kramer's presence as their white director has also been largely credited for the group being able to be booked in places otherwise hostile to blacks.[10]

If I could hear singing like that every morning, my day would be a lot happier.

New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia[75]

Within the program's first 18 months on CBS, Wings had performed in over 150 concerts throughout the East Coast and Midwest.[76] While these tours initially lasted only a matter of days before returning to Cleveland, the choir began receiving fan mail from all over the country as 1938 ended.[77] First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt became one of the choir's most visible supporters, inviting some of the members to a luncheon at the White House on December 5, 1938.[78] This followed three successful engagements in Washington, D.C. and a remote broadcast originating from CBS-owned WJSV,[79] the latter a first for the choir.[80] Roosevelt was later credited in the choir's 1940 Newsweek profile as a fan of the choir.[81] A June 1, 1939, concert at the Baltimore Armory drew a crowd of over 18,000 people; it was immediately followed by an recital at Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church that was a capacity crowd despite little advance promotion.[82] The choir formally incorporated as a non-profit organization in May 1939, initially headquartered at Gethsemane Baptist Church.[83] By May 1941, it moved into the Call and Post building and held offices in Knoxville, New York City, Los Angeles and Atlanta; the black-oriented Call and Post referred to Wings upon this move as "...perhaps one of the Nation's largest Negro enterprises."[84]

Initially, WGAR executive Maurice Condon handled the choir's marketing and management,[55] but by December 1939, Neil Collins was hired as their first promotion director.[77] Working under Worth Kramer, who became the choir's vice president upon incorporation, a full-time position became necessary to handle requests for concerts of all types and sizes.[85] Collins visited approximately 400 radio stations during his 19-month tenure to make necessary arrangements, including all lodging accommodations in segregated towns.[86] Additionally, Collins created the first press kits about the choir, provided advance publicity, and accompanied the choir on tour, making sure all proceeds were distributed appropriately.[77] Like Kramer, Collins was white, which afforded the choir opportunities for concerts and publicity that would not have existed otherwise, with bookings that ranged from nearly empty houses to crowds that refused to leave between concerts, forcing a separate venue to be obtained.[87] Collins later referred to it as "a tour of the United States for a young man, expenses paid".[86] Concert tours during this time included performances on a daily basis, almost always at a different venue, and as many as three different concerts in one day.[88] A March 1940 visit to New York City included Mayor Fiorello La Guardia bestowing the choir a key to the city after they performed in his office, telling the choir, "if I could hear singing like that every morning, my day would be a lot happier".[75] Wings returned to New York City for a performance at the 1939–40 New York World's Fair that July.[89] The largest recorded attendance for any Wings concert took place at Cleveland Municipal Stadium on July 4, 1940, with 75,000 in attendance and 25,000 turned away.[88] Persie Ford was one of several choir members who continuously participated with Wings throughout this period; according to grandson Glenn A. Brackens, she was on the road for a span of nine years[90] while she did take a sabbatical in 1942 to concentrate on her marriage.[10]

Guest speakers[]

Many times, particularly during the '30s and '40s, when there were numerous lynchings or killings of African-Americans in the South, these stories were not carried in depth by the white media. A number of the speakers ... (Rev. Settle) would bring them on, and they would use his Sunday-morning broadcasts as an outlet to help let the world know what was happening and the injustices being done in many areas.

John Foxhall[11]

The guest speaker segment became a regular five-minute feature for the radio program upon the CBS pickup in what was billed as a "round-robin drop" system, allowing the speakers to present their speeches from either Cleveland, New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis or Washington, D.C.[22] Rev. Settle's narrations for each program were carefully written and structured to tie in the song selections—which he had typically chosen beforehand—with the subject material of the guest speakers.[91] Ben A. Green, mayor of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, appeared on the April 10, 1938, program to talk about the town's founding under emancipated slaves; Green was provided a police escort to the WGAR studios and bestowed a key to the city by Cleveland mayor Harold Burton.[92] Bishop Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown, founder of the Palmer Memorial Institute, gave a March 10, 1940, address titled "The Negro and the Social Graces".[93]

The list of guest speakers is voluminous and varied from local church leaders to celebrities, politicians and distinguished scholars. Hattie McDaniel, the first black to win an Academy Award for her role in Gone with the Wind, appeared on the July 7, 1940, program.[94] Historian Dr. Carter G. Woodson gave a February 5, 1939, speech entitled "The Negro's part in history."[95] Channing H. Tobias, president of the YMCA's New York City chapter, talked about that organization's relationship with blacks on March 12, 1939.[96] Francis M. Wood, longstanding director for Baltimore's Negro schools, appeared on the January 21, 1940, installment.[97] E. Washington Rhodes, publisher of The Philadelphia Tribune, delivered "The Fight for Negro Freedom" on September 6, 1942.[98] Additionally, W. E. B. Du Bois, Charles H. Wesley, Langston Hughes and Mary McLeod Bethune[99] have been credited as guest speakers.[12][f] Ohio governor John W. Bricker, Cleveland mayor Harold Burton, New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Coca-Cola Company president George W. Woodruff[101] would be the most prominent white guest speakers. Bricker—who was honored by the Phillis Wheatley Association afterwards—appeared on the program's third anniversary over CBS on January 12, 1941, extended to 45 minutes for the occasion and broadcast from Cleveland's Antioch Baptist Church, the first time a network radio program originated from a black church.[102] Likewise, La Guardia gave an address for the show's fourth anniversary on January 11, 1942.[103] Advance coordination between La Guardia, who gave his remarks in New York City, and the show's production team in Ohio took place via telegraph; the spiritual "When I've Done The Best I've Can" followed the address by request from La Guardia, noting the song's themes of "inconsolation and reward for unappreciated labor".[104]

The presence of these distinguished black artists and scholars[68] on the radio program were revolutionary and further broke color barriers. For the first time on network radio, substantive talks were taking place among black people regarding racial inequities, disfranchisement and suppressive actions like lynching, which were typically avoided by white-controlled media.[11] Because Wings Over Jordan was a sustained radio program and not dependent on commercial sponsors,[69] these speeches were almost always given without any fear of backlash.[11] W. O. Walker's April 12, 1941, Call and Post column noted that black actress Ethel Waters was the first person of color to host a sponsored radio show in 1933 via the American Oil Company, but it was cancelled after stations in the South protested to the network.[105] In contrast, the FCC looked favorably on sustaining programs and frequently used them to help assess if a broadcaster was operating in the public interest.[106] By capitalizing on indifference by white ownership of CBS affiliates in the Deep South, Wings Over Jordan also helped introduce these issues to a white audience for the first time.[11]

International reach[]

The radio program was broadcast live on Sunday mornings throughout its entire run on CBS. Initially airing at 9:00 a.m. Eastern Time,[22] the start time was moved to 9:30 a.m. by September 1938, then to 10:30 a.m. on September 17, 1939.[107] Air times for Wings Over Jordan varied between 9:30 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. for the next two years on a seasonal basis before finally adopting a 10:30 a.m. start on November 2, 1941, directly following Church of the Air on the CBS schedule in all instances.[108] While the later 10:30 a.m. start was meant to accommodate listeners on the West Coast (where it aired at 7:30 a.m. Pacific Time) that were displeased affiliates had to play transcription discs the following week, East Coast listeners were upset over it conflicting with their church's worship services; in an attempt to diffuse the conflict, Rev. Settle suggested that churches broadcast the program to parishioners as a part of their Sunday school curriculum.[101] The most ambitious move, however, took place when CBS offered the choir an additional 15-minute weekday program beginning on July 28, 1941.[109] The choir originated these daily broadcasts out of Cleveland's Euclid Avenue Baptist Church for six weeks after overwhelming demand for tickets and the chapel having an auditorium with a seating capacity of 300 people, much larger than any of WGAR's studios at the Hotel Statler.[110] While merely an experimental program,[106] it was heralded by the Call and Post as "another glorious chapter in (the choir's) unusual success story".[109]

The choir's reach became international in September 1938, when the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) picked up the radio program as part of a goodwill exchange,[111] broadcasting it over their shortwave radio service.[112] By 1939, the radio program was available to stations in Canada, Mexico, South America, India and elsewhere,[83] with the choir receiving congratulatory messages from many of these countries and regions.[65] This international audience was an addition to the existing CBS affiliate base in the United States, which Time estimated in 1940 at 107 stations that carried the program.[68] Shortwave station WRUL in Scituate, Massachusetts, transmitted the program to Europe on December 17, 1940,[102] as part of a "Friendship Bridge" between Great Britain and the U.S.[113] This accentuated the BBC's ongoing relationship with the choir, as their rebroadcasts of Wings Over Jordan had been taking place as part of an ongoing series regarding American music appreciation.[102] CBS selected the choir to be a part of their Columbia School of the Air educational series in 1942, which was transmitted throughout North and South America, bolstering their international presence further.[114]

Acclaim, records and awards[]

And to the men and women of the "Wings Over Jordan" chorus, I found myself saying over and over again: "that crying, your music. It's crying, way down inside. It's crying thousands of years back. It's crying for a God to lead a puzzled and distressed world of men to higher things and things more of the spirit and less of the material... And it will come because underneath it all is a foundation, the foundation of a human spirit which some day, sometime, somewhere will prevail over all else."

Louis B. Seltzer, Cleveland Press editor-in-chief[115]

New York City-based artist management firm Alber-Zwick Corporation signed the choir to an $85,000 contract (equivalent to $1,495,577 in 2020) in January 1941, taking over all aspects of management and talent booking; the signing followed weeks of negotiations that delayed publication of the agency's annual "Alber Blue Book of World Celebrities" so Wings Over Jordan Choir could be included.[116] When asked what helped prompt the agency to affiliate with the choir, Alber-Zwick head Louis Alber cited a January 15, 1941, column from Cleveland Press editor-in-chief Louis B. Seltzer as his justification.[117] Seltzer's column, "There Is A Foundation," was an emotionally-driven response to a Wings recital he had attended at the Hotel Cleveland with several other local dignitaries, lauding the choir and their spiritual repertoire as a direct counterpoint and compliment to the laments of Arab in William Saroyan's play The Time of Your Life.[115][118] Alber, who had been a talent manager for Will Rogers, Lowell Thomas, Vilhjalmur Stefansson and William Howard Taft,[116] said of Seltzer's column, "if you'll read this, you'll understand... the world needs what this Negro Chorus has to give as never before in my lifetime. Louis Seltzer has stated it much better than I can."[117] Alber-Zwick's plans for the choir included additional tours on the West Coast, South America and other world ports, along with potential inclusion in motion pictures.[116]

The program's highest recognition within the radio industry occurred when WGAR and CBS received George Foster Peabody Awards in 1941, the award's inaugural year.[119][120] WGAR won the Peabody for medium-market stations for actively serving Cleveland's ethnic communities and cultural groups, with Wings Over Jordan directly cited as "begun (by the station) five years ago to bring about a better understanding between the white and colored peoples", lauding this and other successes despite the station's (at the time) technically disadvantaged signal.[g][122] CBS was accordingly awarded for public service on the network level, having devoted significant airtime on their broadcast schedule for educational and informative programs.[123] The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), which conducts the award ceremony, directly credited Wings as the reason WGAR and CBS were jointly awarded.[124] Because many of the choir's singers were of a very young age when Settle formed the choir, some singers were reportedly unimpressed with the Peabody Awards[99] but it would be mentioned in press releases for upcoming concerts in the years that followed.[14]

The New York Public Library's Schomburg Collection also placed both Settle and Wings Over Jordan on their Honor Roll of Race Relations,[125] a nationwide poll conducted annually by Dr. Lawrence D. Reddick to recognize people and groups that distinguished themselves with improving race relations "in terms of real democracy."[126] Settle was placed on the 1939 Honor Roll for his role with the program, "outstanding of radio series rendered by Negros the previous year,"[127] and accepted the honor during the February 18, 1940, broadcast.[128] The radio program was placed on the 1941 Honor Roll[129][130] for having successfully reached more listeners than any other program of its kind.[112] CBS, in turn, featured the choir on the front cover of their March 1942 program guide in recognition of this honor.[131][132] Several weeks earlier, Wings Over Jordan commemorated its fifth year on CBS, with the choir boasting that many of their original members were still actively singing with them.[133] Schomburg Collection Honor Roll recipients for 1939, 1943, 1945[126] and 1946[134] were announced live during Wings Over Jordan broadcasts.[135]

April 12, 1941, saw the choir signed to a recording deal with CBS's record division, Columbia Records, for their Masterworks label.[15] A four-disc 78-rpm boxed set album produced by Worth Kramer and narrated by Settle[136] was released the following May.[137][138] As Kramer's commitments to the choir continued to deepen, he started encountering friction among WGAR management who felt he was failing to give enough attention to other artists that had been signed to the station's artists services department.[139][h] With Alber-Zwick now managing all aspects of the choir, Kramer left WGAR and his positions with Wings Over Jordan to become the general manager of WGKV in Charleston, West Virginia, on December 26, 1941, but remained on the choir's board of trustees.[141] The new position at WGKV also included a ownership stake in the station for Kramer which was not disclosed to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) until Kramer neared induction into the U.S. Army at the end of 1943, which temporarily put the station's license in doubt.[142] Still, Kramer was fondly remembered by former singers, Persie Ford recalled that the choir was so responsive to Kramer's direction that it reminded her of "puppets on a string moving only in concert with his fingers".[143]

1942–1946: The war years[]

Emerging OWI alliance[]

The best contributions radio can make to meeting the entire problem (of low morale among blacks) is by remembering Negroes whenever a program is being worked out on which they or their contributions can be included—and included unostentatiously. Many programs are already doing a constructive job in this direction. Some, on the war, have included mention of Negro heroes. Some, on production, have included Negro workers. Others have drawn attention to outstanding Negro cultural contributions to our civilization. All this is a good start—but only a start.

Archibald MacLeish, director of the U.S. OWI's Facts and Figures department, May 30, 1942[144]

The December 7, 1941, broadcast of Wings Over Jordan at 10:30 a.m. Eastern took place like any other broadcast,[145] with Anna M. P. Strong, president of the National Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers, as the guest speaker.[146] Four hours later, news bulletins of the Attack on Pearl Harbor broke, prompting the United States to declare war on Japan, in turn thrusting the U.S. into World War II.[147] Immediately, the subject matter of guest speakers on Wings changed for future broadcasts, with titles like "This troubled world today", "The meaning of democracy", "Towards racial unity in these times", "Divine help in a time of peril" and "Our second emancipation".[148] The changes would be further involved with the United States Office of War Information (OWI) designating Wings Over Jordan as an official source for news items regarding black military personnel and documenting contributions to the war industry by black people.[149] By October 1942, Rev. Settle and OWI radio bureau head William B. Lewis established an arrangement for OWI to provide guest speakers for Wings, along with news bulletins at the beginning of the program.[150] The choir began recording material for the Voice of America (VOA)—which the OWI established as a shortwave counterpropaganda effort—along with transcriptions of the CBS program, but only the songs themselves are confirmed to have been broadcast; this practice would continue until 1946.[151] The radio show was additionally transcribed to the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) and the choir recorded two 78-rpm V-Discs strictly for use overseas.[55]

This partnership was not insignificant. Researchers had actively studied ways to counteract Adolf Hitler's efficiency with multifaceted propaganda, and saw the accidental terror incurred by Orson Welles' The War of the Worlds as a testament to radio's effectiveness on the general public.[152] The OWI's task under director Elmer Davis, a former CBS newsman, was to influence and control opinion with the American populace via radio, and recognized the significant audience Wings enjoyed among blacks regarding said task.[153] The OWI was lobbied significantly by internal advisors and even one anonymous letter sent to the agency,[154] and Davis recognized it was a disservice for the agency to disregard the "state of mind of Negro citizens" as documented in black-owned media.[155] Most existing white-owned media, particularly newspapers and magazines like Life, either ignored black people or downplayed them significantly in coverage.[156] Archibald MacLeish, director of OWI's Facts and Figures department, issued a memo urging the radio industry to develop programming highlighting the contributions of blacks which Billboard magazine published in their June 6, 1942, issue.[144] This memo was sent to all radio networks and stations on May 30, 1942, requesting that they understand the issues of black people and that recognition be given "to the fact that among the 130,000,000 Americans fighting this war for survival, there are 13,000,000 liberty-loving Negroes doing everything they can to win just like everyone else."[157] Legitimate concern existed within the U.S. government of the Axis powers exploiting existing racial tensions through propaganda and manipulation.[158]

We Negros shall face tyranny where ever it exists... and when we have finished assisting America in the battles for human freedom (in Europe and the Pacific Islands), we shall be no less vigilant, no less determined, in breaking off the shackles of oppression form the oppressed here at home. For this is our mission, our destiny, throughout the world. We are the measurements of freedom, the storm troopers of the Rights of Man.

Edwin B. Jourdain, Jr., November 8, 1942[159]

Even with these changes, guests still occasionally approached controversial subjects on-air that involved the war effort. Edwin B. Jourdain, Jr., Evanston, Illinois's first duly-elected black alderman, appeared on the November 8, 1942, program to discuss racial discrimination in the armed forces.[160] His address was done in support of the Double V campaign, launched by the Pittsburgh Courier on February 7, 1942, to rally blacks to fight for democracy both overseas and at the home front, "against our enslavers at home and those abroad who would enslave us."[161] Jourdain asserted the fighting capabilities of black soldiers in the war movement not just to assist in the defeating of the Axis powers, but to work and fight after the war to end oppression; his speech was well-received among the black audience, with Settle calling it "a masterpiece" and multiple requests for written copies, including the OWI itself.[159] The parents of Doris Miller, the first black recipient of the Navy Cross for operating an anti-aircraft gun against Japanese bombers during the Pearl Harbor attack despite no experience, appeared as honored guests on the May 10, 1942, program.[162] Miller's feat was initially anonymous, in fact, he had been inducted into the Schomburg's 1941 Honor Roll of Race Relations alongside the radio program as "an unnamed messman".[130]

Changes and adaptations[]

These were not the only changes the choir faced, as Worth Kramer's departure necessitated a search for a new conductor. Alabama State College professor Dr. Frederick D. Hall was named as interim director with Gladys Olga Jones as his assistant.[163] Existing choir member George McCants served as acting director for at least one performance.[164] Hall's involvement was temporary due to existing commitments at Alabama State, with Jones officially taking over by March.[165] In addition to singing contralto/soprano for the choir,[166] Jones trained under Dr. Hall while a student at Dillard University.[167] This promotion to director after prior work with a Louisiana local church choir was regarded by the Pittsburgh Courier as an "almost fairy-like story"[168] and "a success story of which Dillard is justly proud".[169] Jones' appointment occurred shortly before a March 1942 concert in her hometown of New Orleans which friends and family treated as a homecoming,[170] with similar sentiments held with an August recital.[171] Including Jones, five new singers were introduced into the choir at this time;[170] while many of the original members still remained, the roster of 30 singers included people from 11 different states, primarily the Midwest, Deep South, California and New York.[164] However, Jones held the conductor position briefly and was replaced by Joseph S. Powe by October 1942;[172] like Jones, Powe also studied under Dr. Hall at Dillard.[173] Williette Firmbanks also had left the choir to focus more exclusively on her role as Gethsemane Baptist Church's minister of music.[174]

When this war is over, there shall be no North or South, white or colored, but just all united loyal citizens of the United States.

Rev. Glenn T. Settle, February 28, 1943[175]

Despite all the changes, the choir's performances continued unabated. One tour of the Deep South included a February 28, 1943, Houston, Texas, concert with 4,400 in attendance; the concert's start time was delayed for 30 minutes due to the size of the audience and shortage of seating.[175] A return to Cleveland and Gethsemane on Mother's Day 1943 had Settle and the choir honoring the congregation's mothers, including Settle's late mother Mary B. Settle, and was immediately followed with another Deep South tour.[174] The choir finally took an extended vacation in late July 1943, the first such instance in five and a half years, albeit with commitments to multiple singing engagements in the Cleveland area.[176] The relentless traveling had already prompted Rev. Settle's wife Elizabeth Carter Settle to leave the choir in 1941 to tend to their Cleveland family home, which was seen as a sign of marital estrangement.[55] The choir took advantage of the layover to have their tour bus sent in for maintenance and renovations, boasting numerous conveniences when completed including refrigeration, cooking facilities and restrooms.[176] It is unknown how the choir was able to afford these, let alone basic materials like gasoline and tires, due to wartime rationing.[177]

The vacation in Cleveland also marked the end of Joseph S. Powe's tenure as conductor after 14 months, having left the choir to enlist in the United States Navy.[177] Already a featured soloist, Guthrie, Oklahoma, native Hattye Easley was promptly elevated to the conductor position to highly positive reviews.[176] Settle ultimately hired Maurice Goldman—already an nationally renowned composer and the Cleveland Institute of Music's director of ensemble—to be the permanent conductor in December 1943.[178] Goldman would become the choir's second white director, with Easley retained as his assistant.[179] Goldman's hiring was explained as the result of "a long, patient search" for Worth Kramer's successor that involved all Wings board members including Kramer, and was made with postwar intentions of touring "every country on the globe".[178] Choir member Rev. Henry Payden would later say of Goldman, "he was brilliant, he was excellent, he felt how we (blacks) sang".[180]

USO Europe tour[]

The fame of Wings Over Jordan has not been confined to this musical organization, but has reflected favorably upon the city of Cleveland, and upon Gethsemane Baptist Church itself. Few churches in the nation are better known than this one... Any church would be proud of the honor to have its pastor on a USO tour, bringing joy and inspiration to millions of soldiers lonely for home and peace.

Call and Post editorial, March 10, 1945[181]

The choir's most significant involvement in the war effort came when they were selected by the United Service Organizations (USO) in mid-February 1945 to be part of their Camp Shows unit for six months,[182] providing entertainment for U.S. soldiers on active duty.[183] A collaboration of six social service organizations, the USO was established in 1941 to help with morale among military personnel.[184] While some USO canteens in the U.S. either were integrated or encouraged the practice,[185] others were not. Two former WOJC singers, Paul Breckenridge and Albert Meadows, performed for a black-only audience of 1,000 at Shreveport, Louisiana's Barksdale Air Force Base on January 3, 1945.[186] The USO chose to abide by Jim Crow laws but started arranging camp shows for black troops for two years after having begun them for white troops.[187] The first such "Negro Unit" camp show toured in 1943 with performers Willie Bryant, Kenneth Spencer and Ram Ramirez; upon returning, Bryant said, "the boys want more entertainment and especially live entertainment".[188] The following year, Harlem-based producer Dick Campbell—the USO's coordinator of Camp Show Negro talent—staged the musical Porgy and Bess over a six-month tour.[189] Likewise, Campbell was tasked with overseeing the choir's activities throughout their engagement.[190]

The USO's commission was the first time a religious musical organization had ever been invited and constituted the largest group of entertainers ever taken overseas.[182] For a full year prior, active servicemen and chaplains sent requests to Rev. Settle asking for the choir to perform overseas.[191] A poll that the USO took of servicemen for future camp shows in the fall of 1944 showed the choir beating all other religious and spiritual groups by a commanding margin.[192] Consequently, the radio program was placed on hiatus after 372 consecutive Sunday broadcasts over CBS, with the final broadcast prior taking place on February 25, 1945, at the normal 10:30 a.m. Eastern time; later that evening, the choir was featured on Quentin Reynolds'[193] Radio Reader's Digest dramatizing the history of both the choir and radio program.[194][195] The following day, the group of 20 people[i]—18 choir members including conductor Hattye Easley, Rev. Settle and business manager Mildred Ridley—reported to the USO's New York City headquarters to begin a preparation process that included vaccinations for smallpox, yellow fever and typhoid fever, fittings for uniforms at Saks Fifth Avenue,[187] and securing passports.[197] Cecil Dandy, one of the singers chosen for the USO tour, had a brother returning from active duty in Europe at the same time.[198] CBS assisted with preparation and commissioned a picture of the choir, Settle, Easley and Ridley posing in the V formation which was taken by a Life photographer.[199][200] The Call and Post heralded the choir's tour and Settle in an editorial, considering it Settle's "greatest assignment" and the choir "a beacon light of better racial understanding".[181]

For security purposes, including the threat of aerial and submarine warfare, the choir's departure was kept a military secret.[195] Boarding the USS West Point (AP-23) on March 21, 1945, with approximately 5,000 other military and service personnel, everyone was designated a captain for protective purposes in the event of capture.[201] While in transit, news was received about the death of President Roosevelt, which emotionally affected everyone on board.[202] Landing at Le Havre, France, and transported to Peninsular Base Section (PBS) headquarters in Naples, Italy,[203] the six-month tour in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO) formally began on April 29, 1945.[204] The 98th Regiment of Engineers stationed in Italy constructed a venue for the choir boasting multiple modern lighting and sound features, dubbed "The Wings Over Jordan Stadium".[205] Rev. Settle told the Call and Post that the choir was "setting things on fires", playing to enthusiastic crowds of servicemen.[206] The choir was able to do some sightseeing at both Rome and Vatican City despite performing as much as six days a week.[203] Settle subsequently told a Stars and Stripes reporter, "in some places they've been hanging from the rafters, and they keep shouting their favorites and making requests for numbers we've been singing since 'Wings' was organized".[207] One concert included a prolonged standing ovation as the choir walked out on stage, ended with multiple encores from the audience of G.I.s, and were invited to a social by the company's commanding officer.[205]

With the MTO and ETO[]

We didn’t (travel) like Bob Hope with the pretty girls. We were (called) a foxhole unit, because we had to try to talk to ordinary soldiers who were fighting. We had to go to the hospitals where they were injured.

Kenneth Slaughter[208]

The choir was most closely involved during the first phase of their engagement with the 92nd Infantry Division, an all-black unit led by Major General Edward Almond. Almond invited the choir to sing for the 92nd Division on Easter Sunday 1945, with the choir dedicating "We'll Understand It Better, Bye and Bye" for the entire unit, followed by an impromptu rendition of "My Lord What a Mornin'".[209][72] The choir's arrival also held family bonds: Private first class Carl Slaughter of Columbus, Ohio, was the brother of tour participant Kenneth Slaughter,[210] who had joined the choir in 1942.[208] Settle's conviction about servicemen wanting to turn back to religion was fortified by the choir's two more popular songs being "He'll Understand And Say "Well Done"" and "Just A Closer Walk With Thee".[191] The choir opened a series of concerts to celebrate V-E Day on May 7, 1945, then hosted a Mother's Day program.[205] Their reception among G.I.s was immediately positive, so much so that the choir was promptly offered the full six-month tour commitment.[211] Members of the 92nd Division and the all-white 473rd Infantry Regiment were tasked with finding any remaining Nazi collaborators, liberating both La Spezia and Genoa on April 27, 1945.[212] The rare integrated front lines were likened by Pittsburgh Courier war correspondent Collins George as resembling "a League of Nations, what with Japanese-Americans, American Negros, whites, Brazilians and the British all joined in the inspired race to cover the territory in Northern Italy".[210]

The 92nd Division was most famously tasked with returning a golden urn to Genoa's Municipio purportedly containing the remains of Christopher Columbus in an outdoor ceremony on June 6, 1945, with the 370th Infantry Regiment assisting and the choir performing for all 5,000 servicemen, along with the Genoa citizenry.[213] The townspeople of Genoa requested that the choir perform at the ceremony, which was unprecedented for any occupied European nation[14] but reflective of the attention the choir was garnering with Italians, many of whom were in the audience for the USO Camp Shows.[207] The claims of Columbus' ashes being in the urn were contested even during re-interment, the Encyclopædia Britannica asserted the actual remains were in the Seville Cathedral;[j] the 92nd Division treated the ceremony as returning property moved due to the war[213] while the choir claimed the remains were Columbus's in many postwar promotional stories.[72] According to Mildred Ridley, the choir frequently spent time in infirmaries to spend time with wounded servicemen, ate and socialized in mess halls with G.I.s, and used wit and humor to brighten up the atmosphere during appearances, taking their USO responsibilities to heart.[214] The entire choir, and Settle in particular, received citations from Almond for meritorious service and "fine spirit of patriotism exhibited by the group",[215][216] the highest award given by the military to civilians.[217] Ridley's son, Sergeant Theodore Johnson, presented her with roses when they met in Leghorn.[218]

Well, we've bounced all over Italy, North Africa, Sicily, France, Belgium and Germany in a six by six truck and now these cushions are so soft, I'm afraid to sit down for fear I'll sink through one.

Hattye Easley[216]

The five-month MTO tour for the choir was immediately followed up by a four-month tour in the European Theater of Operations (ETO). Announced by Rev. Settle on September 9, 1945, this extended the choir's USO commitment from six months to ten[219] and directly followed a successful week of engagements in Rome, having performed throughout the entire country.[220] An October 24, 1945, CBS press release cited "urgent appeals from the Special Service section and from many Army chaplains in the ETO" as a reason for the extension.[221][222] The transfer to the ETO took place after reporting in Le Harve on October 6, 1945; while en route, the choir flew to Paris shortly after blackout restrictions were lifted resulting in the city being lit up "like a huge jewel".[223] Settle called the MTO tour "the grandest six months of our career" and prayed for every serviceman to return home to their native lands as soon as possible for "a greater opportunity to serve humanity's cause in a lasting peace, for which they have nobly fought".[224] Three military personnel were assigned to the group, which traveled in a six-by-six truck[216] containing stage equipment including scenery, props and floodlights, a public address system and kerosene-powered stoves.[223] Along with existing material recorded for the VOA, several performances were broadcast live over AFRS, including the Genoa concert and a Christmas program also featuring Red Skelton, Mickey Rooney and Fred Waring's orchestra;[225] the Christmas program was transcribed for broadcast in the U.S.[226] When the ETO phase of the USO tour ended on January 27, 1946, the choir had performed in Le Harve and Paris, the Belgium towns of Brussels, Liège and Antwerp, and the German cities of Bad Nauheim, Frankfurt and Stuttgart.[227] ETO headquarters in Paris also honored Mildred Ridley as the most efficient manager for any overseas Camp Show unit.[216]

By Rev. Settle's suggestion, CBS kept the timeslot active throughout by hosting a rotation of prominent black choirs which performed under the Wings Over Jordan banner, all of which were produced and directed by Settle's son, Glenn Howard Settle.[195] The first choir selected as a "pinch hitter" for Wings were the Fisk University choir, a selection noted for ties to the Jubilee Singers, which in 1871 helped popularize spirituals.[228] Originating from Nashville's WLAC, the Fisk choir's Easter broadcast on April 1, 1945, under the Wings banner was also transmitted overseas via shortwave.[229] Other groups performing in the timeslot included the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina's Choral Society from Greensboro, North Carolina,[230] The Legend Singers of St. Louis,[231] the Camp Meetin' Choir of Charlotte, North Carolina and the Tuskegee Institute Choir of Tuskegee, Alabama.[232] The Fisk University Choir returned to perform in the timeslot during the month of November;[222] this stint was extended into December and included a program of Christmas carols.[233] The Tuskegee Institute Choir was the last group to substitute throughout the month of February 1946, with Wings Over Jordan resuming upon the choir's return on March 3, 1946, concluding a year-long hiatus.[234] The choir returned to the U.S. with the male members sailing on the SS Westminster Victory and the females on the SS Hood Victory,[235] then traveled from New York City back to Cleveland where multiple churches teamed up to host a gala celebration concert.[216] Not all of the singers were present from start to end, as Kenneth Slaughter withdrew after being hospitalized for three weeks, returning to the U.S. in late 1945 with three other singers. While this ended Slaughter's involvement with the choir, the USO issued him and everyone else service awards for their efforts.[208]

1946–1955: Postwar activities[]

Unprecedented touring[]

Following their return in February 1946, and after a few days with family members, the singers immediately launched one of the largest concert tours in the choir's history: between April 1946 and April 1947, the choir traveled over 100,000 miles (160,000 km) and performed in front of over 250,000 people.[236] Highlights included high-profile performances at Madison Square Garden[237] and the Hollywood Bowl, the latter with director James Lewis Elkins personally invited afterwards by New York Philharmonic director Artur Rodziński to perform with the symphony the following spring.[238] On January 7, 1947, the choir bestowed the first winner of a college scholarship bearing their name, with the ceremony being held in Cleveland in recognition of it being the choir's birthplace;[239] Settle promised to name 20 scholarships in music by the end of the year.[236] Demand for concerts was now such that, by November 1946, the choir had the entirety of 1947 and significant portions of 1948 completely booked.[238] Charles King was appointed as the interim conductor in the middle of this tour when Elkins took a brief vacation due to the extensive concert schedule that spanned over 44 states; King's work was so positively received that he and Elkins were named as joint conductors.[240] Elkins was already recognized as the highest-paid black conductor in the country.[236] The choir also now utilized two different buses for traveling, enabling either bus to be properly serviced and maintained without impacting the tour schedule.[241] One of these buses was defaced during a concert in Rockingham, North Carolina, when a white man covered up the signage with aluminum paint; local businessmen promptly provided the choir paint thinner for repairs and the individual was later sentenced to six months on the chain gang and a $500 fine for what the judge called, "tampering with the works of God".[242]

The choir returned to Cleveland for the first time in over one year on May 7, 1947, for a benefit concert at Gethsemane Baptist Church.[243] However, relations between Settle and Gethsemane had deteriorated due to his prolonged absences, with several members holding a 'secret' meeting on April 8, 1946, to render the pulpit as "vacant".[244] Settle voluntarily resigned as pastor in response, admitting he had not served as an active pastor for over a year.[245] As the choir's activities were largely based in New York City and Brooklyn, CBS flagship WCBS was recognized in at least one instance as the originating station for Wings Over Jordan,[243] but due to the extensive touring and lack of definitive records, this might be impossible to determine.[246] Said distinction was likely nominal due to the choir having to originate from a different affiliate every week.[241] Still, construction was underway on a new office building in Cleveland for the choir's administrative functions, and Settle also announced plans for a shrine in honor of his mother that would include an auditorium with a pipe organ and radio facilities.[247] Rev. Glenn Settle even announced a change to the spelling of his first name to Glynn; this followed his being named as heir to ownership of an island in the Dan River via his grandfather's will, which stipulated that the heir had to have "Glynn" and "Settle" in their name.[248] Settle was also admitted into the West Palm Beach Sailfish Club after unexpectedly catching a record-sized sailfish, becoming the fraternity's first black member.[249]

August 1947 walkout[]

I was planning to leave the choir soon, to accept a position as head of the music department at Albany State College... when I told Rev. Settle of my feelings regarding his treatment of choir members, he denounced me bitterly. He told me that I was the worst conductor he had ever had. This, in spite of the fact that out of the 14 conductors he has had in ten years, I am the only one who was ever recognized by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

James Lewis Elkins[250]

The CBS program remained popular even with the 10-month USO tour hiatus. The remote broadcasts timed with their extensive touring—which now totaled 400 different cities in 46 states[251]—now occurred with the choir meeting at the respective affiliate's studios hours in advance.[241] On August 10, 1947, the show celebrated its 500th episode,[251] and the choir embarked on another trip to California that included a cameo in a forthcoming Warner Bros. motion picture.[236] Behind the scenes, however, these postwar activities were taking a substantial toll on the choir's membership. While annual auditions for singers[252] had taken place as early as 1939, they became more extensive after a majority of the original roster departed.[253] By 1942, auditions for singers were held in every town that hosted a concert,[254] a method that yielded 20 singers from fifteen different states.[255] While Wings had approximately 40 singers on the original roster and many were still singing for the radio program's fifth anniversary in 1942,[256] the number decreased to 17 singers in the summer of 1947, with one estimate of as many as 250 people that had participated in the choir in some capacity.[250] Original member Tommy Roberts had rejoined the choir for the postwar tour as a featured soloist and recruited wife Evelyn Freeman Roberts—a classically trained pianist and swing band leader—as an arranger.[257][258] Several months later, Settle fired Evelyn when her work started to rival his in popularity, prompting Tommy to quit in protest, later saying, "when (Settle) fired her, he fired me".[259]

Two weeks after the landmark 500th episode, on August 24, 1947, the choir staged a walkout against Settle by refusing to perform at the San Diego CBS affiliate, having departed the previous night for Los Angeles.[250] Settle's son, Wings business manager Glenn T. Settle, Jr., vowed the choir would return to the radio the following week, referring to the action as a "revolt" and telling the Call and Post, "you can say that the choir is not destroyed... that is all I can say on the record."[260] In addition to the missed radio broadcast, several concerts were cancelled due to the walkout, including one in Tucson.[261] The choir members expressed deep resentment towards Settle, accusing him of inhumane working conditions and low wages.[262] Further allegations were raised of "a total lack of consideration for the members of the organization" as Settle refused to grant any vacation time and laid them off whenever they were not on tour.[250] Several members, including Emory Barnes and John Carpenter, resigned in protest the week prior.[260] Barnes' resignation was over Settle's "unchristian attitude", with Settle accusing him in turn of "being a very miserable failure."[250] None of the singers were salaried employees, which had pressured past singers to leave in order to pursue gainful employment.[263] Typical weekly compensation for singers was only $52.50 (equivalent to $608 in 2020), and conductor James Elkins only receiving $150 (equivalent to $1,739 in 2020), but everyone was responsible for their own expenses outside of travel; Elkins' unrelated planned departure was met with bitter insults from Settle, who claimed Elkins was the worst conductor the choir had ever had, despite the recognition from the New York Philharmonic.[250] While there had been prior walkouts by the choir, this was the first time it prevented an episode of Wings from being broadcast.[264] The members had considered a walkout several months earlier, but felt an obligation to perform for the public and still agreed with the principles behind Settle's Spiritual Preservation Fund.[250]

CBS cancellation and aftermath[]

Settle attempted to resolve the dispute by persuading the singers to return, but only one agreed to do so.[250] In response, Settle dismissed all 17 singers and started a nationwide canvassing effort for replacement singers that included auditions in places like San Angelo, Texas.[265] Among the singers that joined the reconstituted choir were original singers Lois Waterford (Parker) and Olive Thompson;[262] with their return billed as "many original choristers (that) have returned to the organization."[266] CBS ended up cancelling the program after the October 12, 1947, broadcast, offering the timeslot to college chorales from black universities,[264] including the Atlanta-Morehouse-Spelman choir that originated from Atlanta's WGST.[267] Daily Press columnist Paul Luther suggested in his column that the cancellation was only temporary due to the choir's touring that made it difficult to conduct the program from affiliate stations.[268] In later years, director Clarence H. Brooks would state the CBS show ended in order for the choir "to promote Christian fellowship and song".[269] In truth, CBS dropped the program after the no-show and accusations against Settle and stated their move was permanent.[264] Consequently, the choir agreed to go on a tour throughout Mexico throughout November 1947, with the CBS cancellation having played an indirect role.[270] Following that, Wings performed with the San Antonio Symphony on November 22, 1947, a concert seen as an achievement for the choir after having endured discrimination in the city in previous years.[271]

Despite the circumstances leading up to the CBS cancellation, the choir continued to remain a popular concert draw in 1948, performing in 45 of the 48 states and raising over $1 million (equivalent to $10,771,468 in 2020) for various charities.[44] Under newly appointed conductor Gilbert Allen, the choir signed a contract with RCA Records to record songs over the Victor label;[272] the first 78-rpm single, "Until I Found The Lord" and "He'll Understand And Say 'Well Done'", was released in October 1948.[273] It was the third recording deal after prior releases through Columbia and King Records's Queen label.[272] Out of the choir's RCA output, the December 1948 release of "Sweet Little Jesus Boy" and "Amen"[274] were the most popular and enduring. A call-and-response-style hymn,[275] "Amen" would become a staple of concerts and future recordings, and was the title of a 1956 King compilation album.[276] WGAR was already in the process of moving on: earlier in 1947, they debuted a program featuring the local "Dixieteers" quartet that aired on Sunday nights.[277][278] After the cancellation of Wings, WGAR offered a limited-run program in 1948 featuring the "Kingdom Choir", composed of multiple former Wings members and conducted by King.[279] Another program, the Karaleers of Karamu House, was launched over WGAR on January 1, 1950, to positive reception.[280] Meanwhile, Settle would again attract negative publicity after a complaint was filed accusing neglect at his Cleveland residence that presented a fire hazard; the case was settled in court on August 12, 1949, with Settle paying a $250 fine.[281]

A new business model[]

The radio program was revived over the Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS), with the January 9, 1949, debut promoted as the show's 510th episode.[7] At the time, MBS boasted more than 500 affiliates, more than any other U.S. radio network.[k] Despite the show being presented as a continuation of the CBS show, which had been a sustained program, the Mutual version was sponsored by the U.S. Treasury Department as a promotional imitative for their United States Savings Bonds program.[7] Additionally, while guest speakers were still a core feature of the program, the emphasis on their appearances shifted from discussions regarding issues facing black people to "the life stories of prominent American Negroes in words and song".[286] The choir did travel to Mutual affiliates for remote broadcasts, again for the purposes of hosting guest speakers and to accommodate their travel itinerary which involved another tour in the Deep South, as well as recording additional material for RCA Victor.[286] The MBS show was scheduled on a Saturday afternoon for two weeks, then moved to Sundays at 12 p.m.[7] and again to 9:30 a.m. by July.[287] While a similar program featuring different black college choral groups would debut over Mutual on Saturday afternoons,[288] Wings Over Jordan was quietly dropped from the lineup at the end of 1949 when the U.S. Treasury withdrew their sponsorship.[c]

Around this time, press releases for the choir began openly promoting a different business model. While admissions were previously charged and proceeds distributed accordingly,[77] concerts were now free to the public in exchange for any free-will offerings.[291][292] For some concerts, a portion of money raised from donations would go to the Spiritual Preservation Fund, from which the Wings scholarship fund operated from.[293] In some instances, booklets featuring the choir were given Settle instituted this change claiming admissions were now a hindrance for people who wished to attend their concerts[294] and stated it was made "to combat the influence of communism in America as it affects the Negro".[292] Concert reviews would commend the choir for this practice, with one calling it an "unselfish effort".[295] Membership turnover in the choir continued at a frequent pace, with Settle declining to properly integrate some of the newer singers that auditioned; these younger and inexperienced singers were expected to know the repertoire or pantomime their performances, slowly impacting the sound quality and running contrary to the choir's founding principles.[296]

The choir's past reputation still preceded itself as the USO invited Wings to again perform for overseas personnel, this time stationed in Hawaii, the Philippines, South Korea and Japan, starting on December 15, 1953.[297] This was the second time the choir would sing on what were still foreign battlefields.[298] Concerts in South Korea were frequently met with overflowing crowds, prompting the singers to go outside afterwards and visit the crowd overflow, sometimes in sub-zero temperatures.[299] While in Japan, the choir was broadcast over television for the first time, making several appearances over NHK television,[300] and broadcast over radio to all military.[297] In a letter to the Uniontown Evening Standard, Settle expressed intentions to have the choir tour the world as a way to further the fight against communism.[299] Settle's wife Elizabeth Carter Settle accompanied the choir on this tour but otherwise resided in Uniontown;[301] Elizabeth died in Cleveland on May 17, 1955, while visiting one of their daughters.[302] Several days later, on June 1, 1955, Settle married the choir's business manager, Mildred C. Ridley—who had given birth to one of Settle's sons extra-maritally in 1947—and relocated to Los Angeles.[55]

1955–1978: Later performances[]

"Satellite" choirs and reorganizations[]

Now, almost twenty years later, there is no Wings Over Jordan. From national and international tours, world recognition and musical artistry, the singers that were integral parts of this choir have gone their separate ways—some to fame and fortune, some to death, to prison; some to routine living and all to reminiscing.

June Williams, April 13, 1957[303]

Owing to the choir losing all of their original members and continued demand for concert bookings, Settle broke up the choir into several "satellite" groups that would use the Wings name. The Legend Singers of St. Louis—who were one of several substitute choirs on the CBS radio show during the 1945 USO tour[231]—were designated as one of these groups by Settle in January 1950,[304] and were joined by an East Coast choir under Clarence H. Brooks' direction.[305] These were reorganized back into two choruses by 1957: the West Coast group led by Rev. Settle and Frank Everett which boasted 20 singers,[306] and the East Coast group under Brooks that remained at nine singers.[307] This reorganization was billed as a "crusade" on the part of Settle and Everett to preserve spirituals "as an American tradition"[306] and these choirs were now marketed as a "successor to the original great Wings Over Jordan Choir".[308] During this period, several albums were recorded by both choirs: the 1958 Dial title The World's Greatest Negro Choir[309] and the 1960 ABC-Paramount title The World's Greatest Spiritual Singers, the latter celebrating the group's 25th anniversary.[310][311] The ABC-Paramount album was recorded in the auditorium of an abandoned USO building in Mineral Wells, Texas, and the difficulties associated with production were detailed in the album's liner notes.[312] An additional King album of previously released material, An Outstanding Collection of Traditional Negro Spirituals, was also published in 1958.[313]

Both choirs continued touring throughout the next several years throughout the country to varying groups and sizes, with promotional stories typically noting, "the sponsors have expressed confidence that, with this group's fame going ahead of them, the... auditorium will be filled to capacity".[314] Still, an August 1964 tour for the East Coast choir went awry after two planned concerts in Tifton and Brunswick, Georgia, were cancelled on consecutive nights when the choir failed to show up at either venue.[315] This followed a concert in Americus two nights earlier where local police repeatedly pulled them over on suspicions of leading civil rights demonstrations.[316] The two no-shows prompted requests for the Georgia State Patrol to search for the missing group, but a formal all-points bulletin was never issued due to a lack of information including the license plate of the tour bus.[317] All nine singers showed up in Albany the next day for a planned concert at Bethel A.M.E. Church, which was cancelled due to the audience being deemed too small.[318] While the East Coast choir vowed to "press on" with their 1964 tour,[316] it and the West Coast choir folded as the year ended, ending Brooks' tenure as a director.[55] A few months later, Los Angeles musician and composer Leroy Hurte reorganized the West Coast iteration of Wings, briefly directing it along with two other chorales.[319] The extent of Hurte's involvement is undetermined, as Frank Everett would eventually re-assume the director role.[55] The choir performed at an interfaith music program at Settle's First Baptist Church on July 25, 1965, along with other Protestant and Catholic denominations.[320]

Death of Rev. Settle and decline[]

Settle continued to be involved with the choir and music ministries up to his death on July 16, 1967; one week earlier, Settle directed the First Baptist Church's ninth annual Brotherhood Festival in Song.[321] Without Settle's involvement, the choir's activities decreased significantly. A tribute concert to Settle took place at First Baptist on February 16, 1969, with Wings and other choruses singing,[322] while the choir marked its 35th anniversary with an awards banquet on February 21, 1971, at the Hollywood Palladium that also benefited a memorial scholarship under Settle's name.[323] Two additional overseas tours to Japan took place in 1970 and 1972, respectively.[55] Frank Everett's tenure as director is documented to have ended in 1978,[a] even though the last documented concert in the United States under his name took place in Hartford, Connecticut, on April 23, 1972.[324] Widow Mildred Settle reportedly destroyed documents belonging to Settle in 1970, but donated other documents and items pertaining to Wings to the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, including recorded material from an unfinished 1971 album.[55]

Many of the original surviving members would frequently reunite in the years following the original choir's demise. The first major reunion took place on April 14, 1957, commemorating the 20th anniversary of the radio program's launch;[303] many of the surviving members, in addition to some of the show's guest speakers, were in attendance.[325] An annual reunion of Wings alumni started taking place in 1971,[326] with onetime assistant director Willette Firmbanks Thompson heading the alumni association.[327] Firmbanks maintained her role as Gethsemane's minister of music until relinquishing the duties following the death of her husband in 1950; an honorary "Appreciation Tea" was held for Firmbanks by Gethsemane's Senior Choir on February 3, 1952, with multiple parishioners, choir members and civic leaders in attendance, with Rev. Settle, Worth Kramer and congressperson Frances P. Bolton sending cards and telegraphs in recognition.[328]

Legacy[]

Historical appraisals[]

...how well (Glynn T. Settle) has succeeded in bringing closer understanding between black and while has been demonstrated by the Wings' work both in the United States and abroad. Their radio broadcasts were eagerly awaited each week by an integrated public moved by the power and beauty of true American music and the deep richness of faith with permeates the Negro's love for God and their country. ... The basis of the gospel repertoire remains these hymns, just as the essence of the gospel style is a wordless moan. Through the years, they all played their part.

Bill "Hoss" Allen, WLAC personality[329]

Rev. Settle's objectives with the choir upon formation were to help bridge race relations through music and preserve the authenticity of the African-American spiritual,[36] which were successfully met both in the concert hall and on the radio dial. The choir's original members were all parishioners at Gethsemane Baptist Church, a small, modest church near Cleveland's downtown, and were humble lower-class workers and laborers during the Great Depression's peak.[28] While they never had any formal music training until Worth Kramer's involvement, these singers learned how to sing spirituals through oral tradition,[34] having kept the form alive in a pure, authentic manner.[330] This is especially notable as despite popular groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers touring internationally,[32] these songs were not necessarily popular among blacks post-Reconstruction[331] and underwent mutations via minstrel acts and burlesque.[332] Kramer's presence as their white conductor, coupled with his open-minded social beliefs, provided the choir avenues for outreach—a radio show promoted to CBS less than six months after their WGAR debut, integrated concert bookings and a recording contract with a prestigious record label—that would have been otherwise impossible.[333] Additionally, Kramer's musical background and experience in written compositions helped to preserve spirituals in proper print form.[334]