Wyndham New Yorker Hotel

| The New Yorker, A Wyndham Hotel | |

|---|---|

The hotel, with its large "New Yorker" sign | |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | 481 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10001 United States |

| Coordinates | 40°45′10″N 73°59′38″W / 40.75278°N 73.99389°W |

| Opening | 1930 |

| Owner | Unification Church of the United States |

| Management | Wyndham Hotels & Resorts |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 43 (21 for hotel) |

| Floor area | 1,000,000 sq ft (93,000 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Sugarman and Berger |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 1,083 (originally 2,500) |

| Number of suites | 64 |

| Number of restaurants | 2 (originally 5) |

| Website | |

| www.newyorkerhotel.com | |

The New Yorker, A Wyndham Hotel is a 43-story Art Deco hotel located at 481 Eighth Avenue in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, United States. Opened in 1930, it contains 1,083 rooms and is classified as a mid-priced hotel. The 1-million-square-foot (93,000-square-meter) building offers two restaurants and approximately 33,000 square feet (3,100 m2) of conference space.[1]

The New Yorker Hotel was successful in its early years, hosting many famous personalities. In the 1950s, the hotel was sold multiple times, including to Hilton Hotels. By the time Hilton reacquired the New Yorker Hotel in 1967, it had become unprofitable and Hilton closed it in 1972. The Unification Church purchased the building in 1975, and two decades later, elected to convert a portion of the building to use as a hotel again. Since re-opening as a hotel in 1994, the New Yorker Hotel has undergone approximately $100 million in capital improvements, including lobby and room renovations and infrastructure modernization. It has been part of the Wyndham Hotels & Resorts chain since 2014.

History[]

Construction and early years[]

The New Yorker Hotel was built by Garment Center developer Mack Kanner. When the project was announced in 1928, the Sugarman and Berger designed building was planned to be 38 stories, at an estimated cost of $8 million.[2][3] However, when it was completed in 1929, the building had grown to 43 stories, at a final cost of $22.5 million and contained 2,500 rooms, making it the city's largest for many years.[4][5] Hotel management pioneer Ralph Hitz was selected as its first manager, eventually becoming president of the National Hotel Management Company. An early ad for the building boasted that the hotel's "bell boys were 'as snappy-looking as West Pointers'" and "that it had a radio in every room with a choice of four stations".[6] It was a New Yorker bellboy, Johnny Roventini, who served as tobacco company Philip Morris' pitchman for twenty years, making famous their "Call for Philip Morris" advertising campaign.[7]

The hotel opened on January 2, 1930.[8] Much like its contemporaries, the Empire State Building (1931) and the Chrysler Building (1930), the New Yorker was designed in the Art Deco style which was popular in the 1920s and 1930s. In his book New York 1930 Robert A. M. Stern said the "New Yorker's virtually unornamented facades consisted of alternating vertical bands of warm gray brick and windows, yielding an impression of boldly modeled masses. This was furthered by the deep-cut light courts, which produced a powerful play of light and shade that was enhanced by dramatic lighting at night".[9] In addition to the ballrooms there were ten private dining "salons" and five restaurants employing 35 master cooks.[5] There were twenty six murals painted in the hotel by Lajos "Louis" Jambor.[10][11] The barber shop was one of the largest in the world with 42 chairs and 20 manicurists.[5] There were 95 switchboard operators and 150 laundry staff washing as many as 350,000 pieces daily.[5][6]

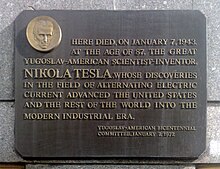

In his final years, the inventor Nikola Tesla lived in the hotel's room 3327 and died there penniless on January 7, 1943.[12]

Mid- and late 20th century[]

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the hotel was among New York's most fashionable. The New York Observer noted that in the building's heyday, "actors, celebrities, athletes, politicians, mobsters, the shady and the luminous—the entire Brooklyn Dodgers roster during the glory seasons—would stalk the bars and ballrooms, or romp upstairs";[1]

In May 1949, the hotel hosted the first concurrent annual meetings of the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association and the International Ice Hockey Federation.[13]

It hosted many popular Big Bands, such as Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey,[14] while notable figures such as Spencer Tracy, Joan Crawford and Fidel Castro stayed there. Inventor Nikola Tesla spent the last ten years of his life in near-seclusion in Suite 3327, where he died, largely devoting his time to feeding pigeons while occasionally meeting dignitaries.[8][15] In later years, Muhammad Ali would recuperate there after his March 1971 fight against Joe Frazier at the Garden.[1][8]

Notwithstanding its early success, New York's changing economy and demographics caused the building to slowly decline and, as a result, its ownership changed several times. It was purchased by Hilton Hotels in 1953 for $12.5 million and following an antitrust suit by the federal government, was sold just three years later, in 1956, for $20 million to Massaglia Hotels.[16][17] In 1959, Massaglia sold the hotel to an investment syndicate known as New York Towers Ltd., which went bankrupt, allowing Hilton to reacquire the building in 1967.[18]

By the time Hilton reacquired the hotel, the pronounced decline in New York's fortunes, coupled with the construction of new, more modern hotels, caused the New Yorker to become unprofitable. As a result, Hilton closed the hotel in April 1972.[14]

Though the building was initially left vacant, several proposals were made, including redevelopment as a low-income housing development, and a hospital.[14] Ultimately, in 1975, it was purchased by the Unification Church of the United States for $5.6 million. The church converted much of the building for use by its members.[19]

Reopening[]

In 1994, the Unification Church elected to convert a portion of the building to use as a hotel again and the New Yorker Hotel Management Company took over operation of the building. It began the largest renovation project in the New Yorker's nearly 65-year history, completed in 1999, with $20 million in capital improvements.[20] The hotel joined the Ramada chain in 2000.

In 2005, the hotel's management began the process of replacing the New Yorker's famous sign, which hadn't been lit since 1967 and was badly in need of repair. The sign was completely replaced by an energy efficient LED sign that was installed in time to celebrate the hotel's 75th anniversary.

A 75th anniversary celebratory event was held at the hotel on December 8, 2005, where the new sign was officially switched on for the first time by Dr. Charles Yang, President of the New Yorker Hotel Management Company, Kevin H. Smith, the hotel's General Manager, Alan Ostroff, of the Cornell University School of Hotel Management, Jeanne Cummins, vocalist of the Bernie Cummins Orchestra, the hotel's house band in the 1930s and Patricia Hitz-Bradshaw, granddaughter of Ralph Hitz, the hotel's first General Manager.[21][22]

In August 2007, the hotel began a second capital improvement program, which was completed in February 2009 at a final cost of $70 million. These improvements increased the number of guest rooms available from 178 in 1994 to 912, located on floors 19 through 40.[23][24]

The renovation project was designed by Stonehill & Taylor Architects.[24] Interior improvements included room restructuring and augmentation (now called "Metro" and "City View" rooms). Other improvements included a refurbished front entrance, lobby redesign, foyer reconstruction, and ballroom renovations. The hotel also expanded its Wi-Fi and PDA support, and added high-definition flat-screen televisions in all rooms. In addition, individual room air-conditioning units were replaced with modern centralized heating and cooling systems throughout the entire hotel. In 2009, conference room space was added to the hotel through the conversion of a defunct Manufacturer's Hanover Bank branch in the hotel, bringing the total meeting space to just over 33,000 square feet (3,100 m2), in two ballrooms and twelve conference rooms.

The New Yorker Hotel joined the Wyndham Hotels chain in March 2014.[25] Wyndham has undertaken additional upgrades to the hotel, including lobby and restaurant renovations, to attract more business travelers in anticipation of the massive Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project to the west.[8]

Power plant[]

When it was built, the New Yorker Hotel had coal-fired steam boilers and generators sufficient to produce more than 2,200 kilowatts of direct current electric power. At the time, this was the largest private power plant in the United States. The hotel's own direct current generators were still in use during the Northeast Blackout of 1965, but by the late 1960s the hotel's power system had been modernized to alternating current.[8][26] In a dedication ceremony held on September 25, 2008, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) named the New Yorker Hotel's direct current power plant a Milestone in Electrical Engineering. A bronze plaque commemorating the achievement was presented to the hotel by IEEE.

References[]

- ^ a b c "Caught Between the Moonies and New York City: The New Yorker Hotel's Office Idea". June 24, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Sexton, R.W. (1929). American Apartment Houses, Hotels, and Apartment Hotels of Today. New York, New York: Architectural Book Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 184–185.

- ^ "Plans for the New Yorker, 38-Story 8th Av. Hotel, Filed". The New York Times. March 3, 1928. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ "GREATER ACTIVITY FOR 34TH STREET; Westerly Blocks Destined to Be an Important Office Building Centre. AMPLE TRANSIT FACILITIES Mack Kanner, Builder of Hotel New Yorker, Predicts Commercial Growth". The New York Times. September 1, 1929. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "The New Yorker, A Wyndham Hotel".

- ^ a b 'One Thousand New York Buildings, by Jorg Brockman and Bill Harris, page 257, Published by Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc., 2002

- ^ "Joseph F. Cullman 3rd, Who Made Philip Morris a Tobacco Power, Dies at 92". The New York Times. May 1, 2004. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Velsey, Kim (November 20, 2014). "Long Famous But Not Quite Fabulous: The New Yorker Hotel". New York Observer. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Patrick; Mellins, Thomas (1987). New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars. New York: Rizzoli. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8478-3096-1. OCLC 13860977.

- ^ "Louis Jambor". A New Yorker State of Mind. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Goodenow, Rachel. "Artist Biography for Louis Jambor". AskArt.com. Zigler Museum. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Phil Mennitti, The Illusion of Democracy: A More Accurate History of the Modern United States (2015), p. 53

- ^ "Hockey Leaders Gather". Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba. May 30, 1949. p. 20.

- ^ a b c Bamberger, Werner (April 20, 1972). "New Yorker Hotel, Sold to Become a Hospital, Closes Doors After 42 Years". The New York Times. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Cooing for a strange genius Bloomberg News, 2008-05-11

- ^ Times, Special To The New York (November 26, 1953). "Hilton Chain Acquiring New Yorker Hotel Here". The New York Times. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Times, Special To The New York (May 15, 1956). "New Yorker Hotel Is Sold by Hilton Group To Massaglia, Owner of chain of 11 Units". The New York Times. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Fried, Joseph P. (December 9, 1967). "New Yorker Hotel Repurchased by Hilton Chain; Purchase Subject to Debts". The New York Times. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Biermans, J. 1986, The Odyssey of New Religious Movements, Persecution, Struggle, Legitimation: A Case Study of the Unification Church Lewiston, New York and Queenston, Ontario: The Edwin Melton Press ISBN 0-88946-710-2

- ^ "Commercial Real Estate; Making New Yorker Hotel New Again". The New York Times. January 6, 1999. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ New Yorker Hotel Press Release

- ^ Roberta on the Arts: New Yorker Hotel's 75th Anniversary Gala and Historic Re-Lighting of its Two-Story Sign

- ^ "New Yorker Hotel embarks on $65 million renovation". Press release.

- ^ a b Johnson, Richard L. "The 912 room New Yorker Hotel Completes Massive 18-month, $70 million Renovation / February 2009". Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ Hotel News Resource (March 3, 2014). "Iconic New Yorker Hotel Joins Wyndham Brand". Hotelnewsresource.com. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Tom Blalock, Powering the New Yorker: A Hotel's Unique Direct Current System, in IEEE Power and Energy Magazine, Jan/Feb 2006

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wyndham New Yorker Hotel. |

- Official website

- Official Chain website

- New York Skyscrapers-Art Deco Page

- Tesla Society.com

- Modern Mechanix: New Yorker Hotel

Coordinates: 40°45′10″N 73°59′38″W / 40.75278°N 73.99389°W

- Skyscraper hotels in Manhattan

- Hotel buildings completed in 1929

- 1930 establishments in New York City

- Art Deco architecture in Manhattan

- Hotels in Manhattan

- Eighth Avenue (Manhattan)

- Hell's Kitchen, Manhattan

- Nikola Tesla

- 34th Street (Manhattan)