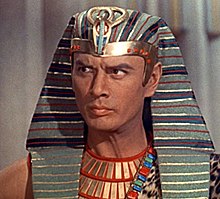

Yul Brynner

Yul Brynner | |

|---|---|

Юл Бринер | |

Brynner in 1960 | |

| Born | Yuliy Borisovich Briner July 11, 1920 |

| Died | October 10, 1985 (aged 65) Manhattan, New York City |

| Resting place | Saint-Michel-de-Bois-Aubry Russian Orthodox Monastery (near Luzé, France) |

| Citizenship | USSR (later renounced) United States (1943–65) Switzerland (1965–85) |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1941–1985 |

| Spouse(s) | Doris Kleiner

(m. 1960; div. 1967)Jacqueline Thion de la Chaume

(m. 1971; div. 1981)Kathy Lee

(m. 1983) |

| Awards | Academy Award for Best Actor 1956 The King and I National Board of Review Award for Best Actor 1956 The King and I 1956 The Ten Commandments 1956 Anastasia Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical 1952 The King and I (and one Special Tony 1985) |

Yuliy Borisovich Briner (Russian: Юлий Борисович Бринер; July 11, 1920 – October 10, 1985), better known as Yul Brynner, was a Russian-American actor, singer, and director, best known for his portrayal of King Mongkut in the Rodgers and Hammerstein stage musical The King and I, for which he won two Tony Awards, and later an Academy Award for Best Actor for the film adaptation. He played the role 4,625 times on stage and became known for his shaved head, which he maintained as a personal trademark long after adopting it for The King and I. Considered one of the first Russian-American film stars,[1] he was honored with a ceremony to put his handprints in front of Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood in 1956, and also received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.

He received the National Board of Review Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Ramesses II in the Cecil B. DeMille epic The Ten Commandments (1956) and General Bounine in the film Anastasia (also 1956). He was also well known as the gunman Chris Adams in The Magnificent Seven (1960) and its first sequel Return of the Seven (1966), along with roles as the android "The Gunslinger" in Westworld (1973), and its sequel, Futureworld (1976).[2] In addition to his film credits, he also worked as a model and photographer and was the author of several books.[3][4]

Early life[]

Yul Brynner was born Yuliy Borisovich Briner [pronounced: Breener; Briner is a common Swiss family name] on July 11, 1920,[5][6][7] in the city of Vladivostok.[8] He had Swiss-German, Russian and Buryat (Mongol) ancestry, and was born at home in a four-story residence at 15 Aleutskaya Street, Vladivostok. He had an elder sister, Vera,[9] a classically trained soprano who sang with the New York City opera.[10]

Brynner enjoyed telling tall tales and exaggerating his background and early life for the press, claiming that he was born "Taidje Khan" of a Mongol father and Roma mother on the Russian island of Sakhalin.[11] He occasionally referred to himself as Julius Briner,[5] Jules Bryner or Youl Bryner.[6] The 1989 biography by his son, Rock Brynner, clarified some of these issues.[11]

His father, Boris Yuliyevich Briner, was a mining engineer and inventor, of Swiss-German and Russian descent. The actor's grandfather, Jules Briner, was a Swiss citizen who moved to Vladivostok in the 1870s and established a successful import/export company.[12] Brynner's paternal grandmother, Natalya Yosifovna Kurkutova, was a native of Irkutsk and a Eurasian of part Buryat ancestry. Brynner's mother, Marousia Dimitrievna (née Blagovidova), hailed from the Russian intelligentsia and studied to be an actress and singer. Brynner felt a strong personal connection to the Romani people; in 1977, Brynner was named honorary president of the International Romani Union, a title that he kept until his death.[13][14]

Boris Briner's work required extensive travel, and in 1923, he fell in love with an actress, Katya Kornukova, at the Moscow Art Theatre, and, soon after, abandoned his family. Yul's mother took his elder sister, Vera (January 17, 1916 – December 13, 1967), and him to Harbin, China, where they attended a school run by the YMCA.[citation needed]

In 1932, fearing a war between China and Japan, she took them to Paris, France.[12] Brynner played his guitar in Russian nightclubs in Paris, sometimes accompanying his sister, playing Russian and Roma songs. He trained as a trapeze acrobat and worked in a French circus troupe for five years,[15] but after sustaining a back injury, he turned to acting.[12][16] In 1938, his mother was diagnosed with leukemia, and they briefly moved back to Harbin.[12]

In 1940, speaking little English, he and his mother immigrated to the United States aboard the President Cleveland, departing from Kobe, Japan, arriving in San Francisco on October 25, 1940. His final destination was New York City, where his sister already lived.[17][6][12] Vera, a singer, starred in The Consul on Broadway in 1950[18] and appeared on television in the title role of Carmen. She later taught voice in New York.[19]

During World War II, Brynner worked as a French-speaking radio announcer and commentator for the US Office of War Information, broadcasting to occupied France.[20] At the same time, he studied acting in Connecticut with the Russian teacher Michael Chekhov.[citation needed]

Career[]

Brynner's first Broadway performance was a small part in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night in December 1941. Brynner found little acting work during the next few years,[12] but among other acting stints, he co-starred in a 1946 production of Lute Song with Mary Martin. He also did some modelling work and was photographed nude by George Platt Lynes.[21]

Brynner's first marriage was to actress Virginia Gilmore in 1944, and soon after he began working as a director at the new CBS television studios, directing Studio One, among other shows. He made his film debut in Port of New York, released in November 1949.[22]

The King and I[]

The next year, at the urging of Martin, he auditioned for Rodgers and Hammerstein's new musical in New York. He recalled that, as he was finding success as a director on television, he was reluctant to go back on the stage. Once he read the script, however, he was fascinated by the character of the King and was eager to perform in the project.[23]

His role as King Mongkut in The King and I (4,625 times on stage) became his best-known role. He appeared in the original 1951 production and later touring productions, as well as a 1977 Broadway revival, a London production in 1979, and another Broadway revival in 1985. He won the Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical for the first of these Broadway productions and a special Tony for the last.[24] He reprised the role in the 1956 film version, for which he won an Academy Award as Best Actor and in Anna and the King, a short-lived TV version on CBS in 1972. Brynner is one of only ten people who have won both a Tony and an Academy Award for the same role.[25] His connection to the story and the role of King Mongkut is so deep that he was mentioned in the Murray Head song "One Night in Bangkok", from the 1984 musical Chess, the second act of which is set in Bangkok.[citation needed]

In 1951, Brynner shaved his head for his role in The King and I.[26][27] Following the huge success of the Broadway production and subsequent film, Brynner continued to shave his head for the rest of his life, though he wore a wig for certain roles. Brynner's shaven head was unusual at the time, and his striking appearance helped to give him an exotic appeal.[28] Some fans shaved off their hair to imitate him,[29] and a shaven head was often referred to as the "Yul Brynner look".[30][31][32]

Films[]

Brynner's second motion picture was the film version of The King and I (1956) with Deborah Kerr. It was a huge success critically and commercially.[33]

Cecil B. de Mille hired him for The Ten Commandments (1956) to play Ramesses II opposite Charlton Heston after seeing him in the stage version of The King and I, telling Brynner backstage that he was the only person for the role.[34] He rounded out his year with Anastasia (1956) co-starring with Ingrid Bergman under the direction of Anatole Litvak. Both films were big hits and Brynner became one of the most in-demand stars in Hollywood[citation needed]

MGM cast him as one of The Brothers Karamazov (1958), which was another commercial success. Less so was The Buccaneer (1958) in which Brynner played Jean Lafitte; he co-starred with Heston and the film was produced by De Mille but directed by Anthony Quinn.

MGM used Brynner again in The Journey (1959), opposite Kerr under the direction of Litvak, but the film lost money. So too did The Sound and the Fury (1959) based on the novel by William Faulkner with Joanne Woodward.

However, Brynner then received an offer to replace Tyrone Power who had died during the making of Solomon and Sheba (1959) with Gina Lollobrigida. The movie was a huge hit, which postponed the development of a planned Brynner film about Spartacus. When the Kirk Douglas film Spartacus (1960) came out, Brynner elected not to make his own version.[35]

Brynner tried comedy with two films directed by Stanley Donen: Once More, with Feeling! (1960) and Surprise Package (1960) but public response was underwhelming. He made a cameo in Testament of Orpheus.[36]

Although the public received him well in The Magnificent Seven (1960) a Western adaptation of Seven Samurai for The Mirisch Company, the picture proved a disappointment upon its initial release in the U.S. However, it was hugely popular in Europe and has had enduring popularity. Its ultimate success led to Brynner's signing a three-picture deal with the Mirisches.[37] The film was especially popular in the Soviet Union, where it sold 67 million tickets.[38] He then made a cameo in Goodbye Again (1961).

Brynner focused on action films. He did Escape from Zahrain (1962) with Ronald Neame as director and Taras Bulba (1962) with Tony Curtis for J. Lee Thompson. Both films were commercial disappointments; Taras Bulba was popular but failed to recoup its large cost.

The first film under his three-picture deal with Mirisch was Flight from Ashiya (1963) with George Chakiris. It was followed by Kings of the Sun (1963), also with Chakiris, directed by Thompson. Neither film was particularly popular; nor was Invitation to a Gunfighter (1964), a Western. Morituri (1965), opposite Marlon Brando, failed to reverse the series of unsuccessful movies. He had cameos in Cast a Giant Shadow (1966) and The Poppy Is Also a Flower (1966).[2]

Brynner enjoyed a hit with Return of the Seven (1966), reprising his role from the original. Less popular was Triple Cross (1966), a war movie with Christopher Plummer; The Double Man (1967), a spy thriller; The Long Duel (1967), an Imperial adventure tale opposite Trevor Howard; Villa Rides (1968), a Western; and The File of the Golden Goose (1969).[2]

Brynner went to Yugoslavia to star in a war film, Battle of Neretva (1969). He supported Katharine Hepburn in the big-budget flop The Madwoman of Chaillot (1969). Brynner appeared in drag (as a torch singer) in an unbilled role in the Peter Sellers comedy The Magic Christian (1969).[40]

Later career[]

Brynner went to Italy to make a Spaghetti Western, Adiós, Sabata (1970) and supported Kirk Douglas in The Light at the Edge of the World (1971). He remained in lead roles for Romance of a Horsethief (1971) and a Western Catlow (1971).[2]

Brynner had a small role in Fuzz (1972)[2] then reprised his most famous part in the TV series Anna and the King (1972) which ran for 13 episodes.

After Night Flight from Moscow (1973) in Europe, Brynner created one of his iconic roles in the cult hit film Westworld (1973) as the 'Gunslinger', a killer robot. His next two films were variations on this performance: The Ultimate Warrior (1975) and Futureworld (1976).[2]

Brynner returned to Broadway in Home Sweet Homer, a notorious flop musical. His final movie was Death Rage (1976), an Italian action film.

Personal life[]

Brynner married four times, his first three marriages ending in divorce. He fathered three children and adopted two. His first wife (1944–1960) was actress Virginia Gilmore with whom he had one child, Yul "Rock" Brynner (born December 23, 1946). He was nicknamed "Rock" when he was six years old in honor of boxer Rocky Graziano. He is a historian, novelist, and university history lecturer at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, New York and Western Connecticut State University in Danbury, Connecticut.

In 2006, Rock wrote a book about his father and his family history titled Empire and Odyssey: The Brynners in Far East Russia and Beyond. He regularly returned to Vladivostok, the city of his father's birth, for the "Pacific Meridian" Film Festival.

Yul Brynner had a long affair with Marlene Dietrich, who was 19 years his senior, beginning during the first production of The King and I.[41]

In 1959, Brynner fathered a daughter, Lark Brynner, with Frankie Tilden, who was 20 years old. Lark lived with her mother and Brynner supported her financially. His second wife, from 1960 to 1967, Doris Kleiner is a Chilean model whom he married on the set during shooting of The Magnificent Seven in 1960. They had one child, Victoria Brynner (born November 1962), whose godmother was Audrey Hepburn.[42] Belgian novelist and artist Monique Watteau was also romantically linked with Brynner, from 1961 to 1967.[43]

His third wife (1971–1981), Jacqueline Simone Thion de la Chaume (1932–2013), a French socialite, was the widow of Philippe de Croisset (son of French playwright Francis de Croisset and a publishing executive). Brynner and Jacqueline adopted two Vietnamese children: Mia (1974) and Melody (1975). The first house Brynner owned was the Manoir de Criqueboeuf, a 16th-century manor house in northwestern France that Jacqueline and he purchased.[44] His third marriage broke up, reportedly owing to his 1980 announcement that he would continue in the role of the King for another long tour and Broadway run, as well as his affairs with female fans and his neglect of his wife and children.[45]

On April 4, 1983, aged 62, Brynner married his fourth and final wife, Kathy Lee (born 1957), a 26-year-old ballerina from Ipoh, Malaysia, whom he had met in a production of The King and I. They remained married for the last two years of his life. His longtime close friends Meredith A. Disney and her sons Charles Elias Disney and Daniel H. Disney attended Brynner and Lee's final performances of The King and I.[46]

Although Brynner had become a naturalized U.S. citizen, aged 22, in 1943, while living in New York as an actor and radio announcer,[6] he renounced his US citizenship at the U.S. Embassy in Bern, Switzerland, in June 1965 because he had lost his tax exemption as an American resident working abroad. He had stayed too long in the United States meaning he would be bankrupted by his tax and penalty debts imposed by the Internal Revenue Service.[44]

Other interests[]

In addition to his work as a director and performer, Brynner was an active photographer and wrote two books. His daughter Victoria put together Yul Brynner: Photographer (ISBN 0-8109-3144-3), a collection of his photographs of family, friends, and fellow actors, as well as those he took while serving as a UN special consultant on refugees.[47][48][49]

Brynner wrote Bring Forth the Children: A Journey to the Forgotten People of Europe and the Middle East (1960), with photographs by himself and Magnum photographer Inge Morath, and The Yul Brynner Cookbook: Food Fit for the King and You (1983 ISBN 0-8128-2882-8).

He was also an accomplished guitarist and singer. In his early period in Europe, he often played and sang gypsy songs in Parisian nightclubs with Aliosha Dimitrievitch. He sang some of those same songs in the film The Brothers Karamazov.[citation needed] In 1967, Dimitrievitch and he released a record album The Gypsy and I: Yul Brynner Sings Gypsy Songs (Vanguard VSD 79265).

Health[]

In September 1983, Brynner found a lump on his vocal cords. In Los Angeles, only hours before his 4,000th performance in The King and I, he received the test results indicating that while his throat was fine, he had inoperable lung cancer. Cigarette smoking is by a substantial margin the greatest risk factor for lung cancer, and Brynner began smoking heavily aged 12. Although he had quit in 1971, his promotional photos often still showed him with a cigarette in hand. He and the national tour of the musical were forced to take a few months off while he underwent radiation therapy which damaged his throat and made it impossible for him to sing or speak easily.[12] The tour then resumed.[50][51]

In January 1985, the tour reached New York for a farewell Broadway run. Aware he was dying, Brynner gave an interview on Good Morning America discussing the dangers of smoking and expressing his desire to make an anti-smoking commercial. The Broadway production of The King and I ran from January 7 to June 30 of that year, with Mary Beth Peil as Anna. His last performance, a few months before his death, marked the 4,625th time he had played the role of the King.

Death[]

Brynner died of lung cancer on October 10, 1985, at New York Hospital at the age of 65.[52][53] Brynner was buried in the grounds of the Saint-Michel-de-Bois-Aubry Orthodox monastery, near Luzé, between Tours and Poitiers in France.[54]

Anti-smoking campaign[]

Prior to his death, with the assistance of the American Cancer Society, Brynner created a public service announcement using a clip from the Good Morning America interview. A few days after his death, it premiered on all major US television networks and in other countries. Brynner used the announcement to express his desire to make an anti-smoking commercial after discovering he had cancer, and that his death was imminent. He then looked directly into the camera for 30 seconds and said, "Now that I'm gone, I tell you: Don't smoke. Whatever you do, just don't smoke. If I could take back that smoking, we wouldn't be talking about any cancer. I'm convinced of that." His year of birth, in one version of the commercial, was incorrectly given as 1915.[55]

Memorial[]

On September 28, 2012, a 2.4-m-tall statue was inaugurated at Yul Brynner Park, in front of the home where he was born at Aleutskaya St. No. 15 in Vladivostok, Russia. Created by local sculptor Alexei Bokiy, the monument was carved in granite from China. The grounds for the park were donated by the city of Vladivostok, which also paid additional costs. Vladivostok Mayor Igor Pushkariov, US Consul General Sylvia Curran, and Yul's son, Rock Brynner, participated in the ceremony, along with hundreds of local residents.[56]

Awards[]

- In 1952, he received the Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical for his portrayal of the King in The King and I. In 1985, he received a special Tony Award honoring his 4625 performances in The King and I.[57]

- He won the 1956 Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of the King of Siam in the film version of The King and I,[58] and made the "Top 10 Stars of the Year" list in both 1957 and 1958.

- In 1960, he was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame with a motion pictures star at 6162 Hollywood Boulevard.[59]

Filmography[]

Short subjects:

- On Location with Westworld (1973)

- Lost to the Revolution (1980) (narrator)

Box office ranking[]

At the height of his career, Brynner was voted by exhibitors as among the most popular stars at the box office:

- 1956 – 21st (US)

- 1957 – 10th (US), 10th (UK)

- 1958 – 8th (US)

- 1959 – 24th (US)

- 1960 – 23rd (US)

Select stage work[]

- Twelfth Night (1941) (Broadway)

- Lute Song (1946) (Broadway and US national tour)

- The King and I (1951) (Broadway and US national tour)

- Home Sweet Homer (1976) (Broadway)

- The King and I (1977) (Broadway, London and US national tour)

- The King and I (1985) (Broadway)

References[]

- ^ Obituary Variety, October 16, 1985.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Yul Brynner Filmography" tcm.com, retrieved May 30, 2019

- ^ "Yul Brynner: A Photographic Journey". yulbrynnerphotographer.com. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ "Yul Brynner's books". Goodreads. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Record of Yul Brynner, #108-18-2984. Social Security Administration. Born in 1920 according to the Social Security Death Index (although some sources indicate the year was 1915) Archived November 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Provo, Utah: MyFamily.com, Inc., 2006.

In his biography of his father, Rock Yul Brynner, he asserts that he was born in the later year (1920). - ^ Jump up to: a b c d United States Declaration of Intent (Document No. 541593), Record Group 21: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685–2004, filed June 4, 1943

- ^ "Famous Gypsies". www.imninalu.net.

- ^ "Yul Brynner Biography". bio.. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ "Briner Residence". Archived from the original on August 22, 2009.

- ^ "Bryner, Vera (d.1967)," encyclopedia.com. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brynner, Rock. Yul: The Man Who Would Be King Berkeley Books: 1991; ISBN 0-425-12547-5

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Rochman, Sue. "A King's Legacy" Archived November 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Cancer Today magazine, Winter 2011 (December 5, 2011). Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Daniel C. Blum (1954). Great Stars of the American Stage. Grosset & Dunlap. p. 137.

- ^ Pankok, Moritz (April 12, 2015). "The Roma Theatre Pralipe". romarchive.eu. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ^ "Yul Brynner Interview with Bill Boggs" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Seiler, Michael. "Yul Brynner Dies at 65; 30 Years in King and I", Los Angeles Times, October 10, 1985. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ "FamilySearch.org".

- ^ Vera Brynner, at the Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Company, Johnson Publishing (October 23, 1966). "Ebony". Johnson Publishing Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Brynner, Rock. Yul: The Man Who Would Be King (p. 30) Berkeley Books: 1991. ISBN 0-425-12547-5

- ^ Leddick, David. George Platt Lynes. New York: Taschen, 2000.

- ^ " 'Port of New York' Notes" tcm.com, retrieved May 30, 2019

- ^ Capua, pp. 26, 28

- ^ "Winners". www.tonyawards.com.

- ^ "tonyawards.com".

- ^ "Yul Brynner, 65, dies of cancer in N.Y. hospital". The Baltimore Sun. October 10, 1985.

- ^ "'Lost' actor stars in West End's 'King'". UPI.com.

- ^ Brynner, Rock (2006). Empire & odyssey: the Brynners in Far East Russia and beyond. Steerforth Press.

- ^ Crouse, Richard (2005). Reel Winners: Movie Award Trivia. Dundurn. p. 171.

- ^ Doyle, Hubert (2008). Ventures with the World of Celebrities, Movies & TV. ISBN 9780976867760.

- ^ Douty, Linda (2011). How Did I Get to Be 70 When I'm 35 Inside?: Spiritual Surprises of Later Life. ISBN 9781594732973.

- ^ Yacowar, Maurice (1999). The Bold Testament. ISBN 9781896209319.

- ^ Miller, Frank. The King and I tcm.com, retrieved May 30, 2019

- ^ "Yul Brynner: The Ten Commandments". Youtube.com. Janson Media. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ "Future Still in Doubt for Power's Last Film: One of 3 Coproducers Reportedly Engaged Yul Brynner Without Consulting Partners". Los Angeles Times. November 19, 1958. p. 28.

- ^ Monaco, James (1991). The Encyclopedia of Film. Perigee Books. pp. 121. ISBN 9780399516047.

- ^ "Looking at Hollywood: Yul Brynner, Mirisch Co. Ink 12 Million Dollar Pact" Hopper, Hedda. Chicago Daily Tribune July 6, 1961: c8.

- ^ ""Великолепная семерка" (The Magnificent Seven, 1960)". KinoPoisk (in Russian). Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ "Fifty Years ago on This Day there were 6.000 Guests at the Opening of Skenderija". Sarajevo Times. November 27, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ Krafsur, Richard P., ed. American Film Institute Catalog, Feature Films 1961–1970 (p. 662), R.R. Bowker Company, 1976; ISBN 0-8352-0453-7

- ^ Capua, chapter 5; "Noël Coward: 'Get on with living and enjoy it!'", The Telegraph, November 11, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ Yul Brynner profile at elsur.cl Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Matthys, Francis (August 15, 2002), "Alika Lindbergh, construite pour l'amour fou", La Libre Belgique, retrieved March 14, 2015

- ^ Jump up to: a b Capua, Michelangelo (2006). Yul Brynner, A Biography. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2461-3.

- ^ Capua, p 151.

- ^ tv.com. "Yul Brynner biography".

- ^ King, Susan. "Seeing World Through Eyes of Yul Brynner, Photographer" Los Angeles Times, December 14, 1996

- ^ Davies, Lucy. "Yul Brynner: a photographic journey" Telegraph, January 14, 2012

- ^ Yul Brynner Photographer Publishers Weekly, ISBN 978-0-8109-3144-2, retrieved May 30, 2019

- ^ Capua, pp. 151–157

- ^ Rosenfeld, Megan."Classic King and I". The Washington Post, December 6, 1984, p. B13. Retrieved December 28, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ ""A King's Legacy", Cancer Today magazine, Winter 2011". Archived from the original on November 2, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ Anti-smoking PSA on YouTube

- ^ "ABBAYE ROYALE SAINT-MICHEL DE BOIS-AUBRY: in LUZE, The Loire Valley, a journey through France". Val de Loire, une balade en France.

- ^ Anti-smoking PSA, wrong birth year on YouTube

- ^ "Rock Brynner in the Russian Far East". www.rockbrynner.com. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ zas IBDb profile

- ^ "The 29th Academy Awards (1957) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame – Yul Brynner". walkoffame.com. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

Further reading[]

- Capua, Michelangelo (2006). Yul Brynner: A Biography. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2461-3.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yul Brynner. |

- Yul Brynner at the Internet Broadway Database

- Yul Brynner at IMDb

- Yul Brynner at the TCM Movie Database

- Yul Brynner at AllMovie

- Yul Brynner at Find a Grave

- 1920 births

- 1985 deaths

- 20th-century male singers

- 20th-century Russian male actors

- American people of Buryat descent

- American people of Mongolian descent

- American people of Russian descent

- American people of Swiss-German descent

- American male musical theatre actors

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Burials in France

- Deaths from cancer in New York (state)

- Deaths from lung cancer

- Donaldson Award winners

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States

- Former United States citizens

- Male Spaghetti Western actors

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- People from Vladivostok

- People of the United States Office of War Information

- Russian male film actors

- Russian male television actors

- Russian male stage actors

- Russian people of Buryat descent

- Russian people of Mongolian descent

- Russian people of Swiss descent

- Russian Romani people

- Soviet emigrants to the United States

- Special Tony Award recipients

- Tony Award winners