Yuri Knorozov

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Yuri Knorozov | |

|---|---|

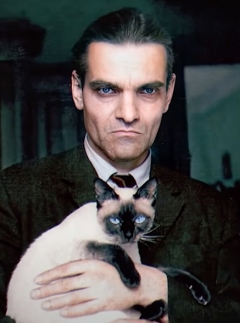

Knorozov with his Siamese cat Aspid | |

| Born | Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov Юрий Валентинович Кнорозов 19 November 1922 |

| Died | 31 March 1999 (aged 76) Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation |

| Citizenship |

|

| Known for | Decipherment of Maya script |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Moscow State University |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Linguist, epigrapher |

| Institutions | N.N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnography and Anthropology |

| Influenced | Galina Yershova |

Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov (alternatively Knorosov; Russian: Ю́рий Валенти́нович Кноро́зов; 19 November 1922 – 31 March 1999) was a Soviet linguist,[1] epigrapher and ethnographer, who is particularly renowned for the pivotal role his research played in the decipherment of the Maya script, the writing system used by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization of Mesoamerica.[2]

Early life[]

Knorozov was born in the village of Pivdenne near Kharkiv, at that time the capital of the newly formed Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic.[3] His parents were Russian intellectuals, and his paternal grandmother Maria Sakhavyan had been a stage actress of national repute in Armenia.[4]

At school, the young Yuri was a difficult and somewhat eccentric student, who made indifferent progress in a number of subjects and was almost expelled for poor and willful behaviour. However, it became clear that he was academically bright with an inquisitive temperament; he was an accomplished violinist, wrote romantic poetry and could draw with accuracy and attention to detail.[5]

In 1940 at the age of 17, Knorozov left Kharkiv for Moscow where he commenced undergraduate studies in the newly created Department of Ethnology[6] at Moscow State University's department of History. He initially specialised in Egyptology.[7]

Military service and the "Berlin Affair"[]

Knorozov's study plans were soon interrupted by the outbreak of World War II hostilities along the Eastern Front in mid-1941. From 1943 to 1945 Knorozov served his term in the second world war in the Red Army as an artillery spotter.[8]

At the closing stages of the war in May 1945, Knorozov and his unit supported the push of the Red Army vanguard into Berlin. It was here, sometime in the aftermath of the Battle of Berlin, that Knorozov is supposed to have by chance retrieved a book which would spark his later interest in and association with deciphering the Maya script. In their retelling, the details of this episode have acquired a somewhat folkloric quality, as "...one of the greatest legends of the history of Maya research".[9] The story has been much reproduced, particularly following the 1992 publication of Michael D. Coe's Breaking the Maya Code.[10]

According to this version of the anecdote, when stationed in Berlin, Knorozov came across the National Library while it was ablaze. Somehow Knorozov managed to retrieve from the burning library a book, which remarkably enough turned out to be a rare edition[11] containing reproductions of the three Maya codices which were then known—the Dresden, Madrid and Paris codices.[12] Knorozov is said to have taken this book back with him to Moscow at the end of the war, where its examination would form the basis for his later pioneering research into the Maya script.

However, in an interview conducted a year before his death, Knorozov provided a different version of the anecdote.[13] As he explained to his interlocutor, the Mayanist epigrapher of the University of Helsinki:

"Unfortunately it was a misunderstanding: I told about it [finding the books in the library in Berlin] to my colleague Michael Coe, but he didn't get it right. There simply wasn't any fire in the library. And the books that were in the library, were in boxes to be sent somewhere else. The fascist command had packed them, and since they didn't have time to move them anywhere, they were simply taken to Moscow. I didn't see any fire there."[14]

The "National Library" mentioned in these accounts is not specifically identified by name, but at the time the library then known as the Preußische Staatsbibliothek (Prussian State Library) had that function. Situated on Unter den Linden and today known as the Berlin State Library (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), this was the largest scientific library of Germany. During the war, most of its collection had been dispersed over some 30 separate storage places across the country for safe-keeping. After the war much of the collection was returned to the library. However, a substantial number of volumes which had been sent for storage in the eastern part of the country were never recovered, with upwards of 350,000 volumes destroyed and a further 300,000 missing. Of these, many ended up in Soviet and Polish library collections, and in particular at the Russian State Library in Moscow.[15]

According to documentary sources, the so-called "Berlin Affair" is just one of many legends related to the personality of Knorozov. His student Ershova exposed it as merely a legend and also reported that documents belonging to Knorozov, such as his military I.D. card, could prove that he did not take part in the Battle of Berlin and was in a different place at the time, finishing his service in a military unit located near Moscow.[16]

Resumption of studies[]

Any possible system made by a man can be solved or cracked by a man.

Yuri Knorozov (1998), St. Petersburg. Interview published in Revista Xamana (Kettunen 1998a)

In the autumn of 1945 after World War II, Knorozov returned to Moscow State University to complete his undergraduate courses at the department of Ethnography. He resumed his research into Egyptology, and also undertook comparative cultural studies in other fields such as Sinology. He displayed a particular interest and aptitude for the study of ancient languages and writing systems, especially hieroglyphs, and he also read in medieval Japanese and Arabic literature.[5]

While still an undergraduate at MSU, Knorozov found work at the N.N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology[17] (or IEA), part of the prestigious Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Knorozov's later research findings would be published by the IEA under its imprint.

As part of his ethnographic curriculum Knorozov spent several months as a member of a field expedition to the Central Asian Soviet republics of the Uzbek and Turkmen SSRs (what had formerly been the Khorezm PSR, and would much later become the independent nations of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan following the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union). On this expedition his ostensible focus was to study the effects of Russian expansionary activities and modern developments upon nomadic ethnic groups, of what was a far-flung frontier world of the Soviet state.[18]

At this point the focus of his research had not yet been drawn on the Maya script. This would change in 1947, when at the instigation of his professor, Knorozov wrote his dissertation on the "de Landa alphabet", a record produced by the 16th century Spanish Bishop Diego de Landa in which he claimed to have transliterated the Spanish alphabet into corresponding Maya hieroglyphs, based on input from Maya informants.[citation needed] De Landa, who during his posting to Yucatán had overseen the destruction of all the codices from the Maya civilization he could find, reproduced his alphabet in a work (Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán) intended to justify his actions once he had been placed on trial when recalled to Spain. The original document had disappeared, and this work was unknown until 1862 when an abridged copy was discovered in the archives of the Spanish Royal Academy by the French scholar, Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg.[citation needed]

Since de Landa's "alphabet" seemed to be contradictory and unclear (e.g., multiple variations were given for some of the letters, and some of the symbols were not known in the surviving inscriptions), previous attempts to use this as a key for deciphering the Maya writing system had not been successful.[citation needed]

Key research[]

In 1952, the then 30-year-old Knorozov published a paper which was later to prove to be a seminal work in the field (Drevnyaya pis’mennost’ Tsentral’noy Ameriki, or "Ancient Writing of Central America".) The general thesis of this paper put forward the observation that early scripts such as ancient Egyptian and Cuneiform which were generally or formerly thought to be predominantly logographic or even purely ideographic in nature, in fact contained a significant phonetic component. That is to say, rather than the symbols representing only or mainly whole words or concepts, many symbols in fact represented the sound elements of the language in which they were written, and had alphabetic or syllabic elements as well, which if understood could further their decipherment. By this time, this was largely known and accepted for several of these, such as Egyptian hieroglyphs (the decipherment of which was famously commenced by Jean-François Champollion in 1822 using the tri-lingual Rosetta Stone artefact); however the prevailing view was that Mayan did not have such features. Knorozov's studies in comparative linguistics drew him to the conclusion that the Mayan script should be no different from the others, and that purely logographic or ideographic scripts did not exist.[citation needed]

Knorozov's key insight was to treat the Maya glyphs represented in de Landa's alphabet not as an alphabet, but rather as a syllabary. He was perhaps not the first to propose a syllabic basis for the script, but his arguments and evidence were the most compelling to date. He maintained that when de Landa had commanded of his informant to write the equivalent of the Spanish letter "b" (for example), the Maya scribe actually produced the glyph which corresponded to the syllable, /be/, as spoken by de Landa. Knorozov did not actually put forward many new transcriptions based on his analysis, nevertheless he maintained that this approach was the key to understanding the script. In effect, the de Landa "alphabet" was to become almost the "Rosetta stone" of Mayan decipherment.[citation needed]

A further critical principle put forward by Knorozov was that of synharmony. According to this, Mayan words or syllables which had the form consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) were often to be represented by two glyphs, each representing a CV-syllable (i.e., CV-CV). In the reading, the vowel of the second was meant to be ignored, leaving the reading (CVC) as intended. The principle also stated that when choosing the second CV glyph, it would be one with an echo vowel that matched the vowel of the first glyph syllable. Later analysis has proved this to be largely correct.[citation needed]

Critical reactions to his work[]

Upon the publication of this work from a then hardly known scholar, Knorozov and his thesis came under some severe and at times dismissive criticism. J. Eric S. Thompson, the noted British scholar regarded by most as the leading Mayanist of his day, led the attack. Thompson's views at that time were solidly anti-phonetic, and his own large body of detailed research had already fleshed-out a view that the Maya inscriptions did not record their actual history, and that the glyphs were founded on ideographic principles. His view was the prevailing one in the field, and many other scholars followed suit.[citation needed]

According to Michael Coe, “during Thompson’s lifetime, it was a rare Maya scholar who dared to contradict” him on the value of Knorozov’s contributions or on most other questions. As a result, decipherment of Maya scripts took much longer than their Egyptian or Hittite counterparts and could only take off after Thompson’s demise in 1975.[19]

The situation was further complicated by Knorozov's paper appearing during the height of the Cold War, and many were able to dismiss his paper as being founded on misguided Marxist-Leninist ideology and polemic. Indeed, in keeping with the mandatory practices of the time, Knorozov's paper was prefaced by a foreword written by the journal's editor which contained digressions and propagandist comments extolling the State-sponsored approach by which Knorozov had succeeded where Western scholarship had failed. However, despite claims to the contrary by several of Knorozov's detractors, Knorozov himself never did include such polemic in his writings.[citation needed]

Knorozov persisted with his publications in spite of the criticism and rejection of many Mayanists of the time. He was perhaps shielded to some extent from the ramifications of peer disputation, since his position and standing at the institute was not adversely influenced by criticism from Western academics.[citation needed]

Progress of decipherment[]

Knorozov further improved his decipherment technique in his 1963 monograph "The Writing of the Maya Indians"[5] and published translations of Mayan manuscripts in his 1975 work "Maya Hieroglyphic Manuscripts".[citation needed]

During the 1960s, other Mayanists and researchers began to expand upon Knorozov's ideas. Their further field-work and examination of the extant inscriptions began to indicate that actual Maya history was recorded in the stelae inscriptions, and not just calendric and astronomical information. The Russian-born but American-resident scholar Tatiana Proskouriakoff was foremost in this work, eventually convincing Thompson and other doubters that historical events were recorded in the script.[citation needed]

Other early supporters of the phonetic approach championed by Knorozov included Michael D. Coe and David Kelley, and whilst initially they were in a clear minority, more and more supporters came to this view as further evidence and research progressed.[citation needed]

Through the rest of the decade and into the next, Proskouriakoff and others continued to develop the theme, and using Knorozov's results and other approaches began to piece together some decipherments of the script. A major breakthrough came during the first round table or Mesa Redonda conference at the Maya site of Palenque in 1973, when using the syllabic approach those present (mostly) deciphered what turned out to be a list of former rulers of that particular Maya city-state.[citation needed]

Subsequent decades saw many further such advances, to the point now where quite a significant portion of the surviving inscriptions can be read. Most Mayanists and accounts of the decipherment history apportion much of the credit to the impetus and insight provided by Knorozov's contributions, to a man who had been able to make important contributions to the understanding of this distant, ancient civilisation.[citation needed]

In retrospect, Prof. Coe writes that "Yuri Knorozov, a man who was far removed from the Western scientific establishment and who, prior to the late 1980s, never saw a Mayan ruin nor touch a real Mayan inscription, had nevertheless, against all odds, “made possible the modern decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing.”[citation needed]

Later life[]

Knorozov had presented his work in 1956 at the International Congress of Americanists in Copenhagen, but in the ensuing years he was not able to travel abroad at all. After diplomatic relations between Guatemala and the Soviet Union were restored in 1990, Knorozov was invited by President Vinicio Cerezo to visit Guatemala. President Cerezo awarded Knorozov the Order of the Quetzal and Knorozov visited several of the major Mayan archaeological sites, including Tikal. The government of Mexico awarded Knorozov the Order of the Aztec Eagle, the highest decoration awarded by the Mexican state to non-citizens, in a ceremony at the Mexican Embassy in Moscow on November 30, 1994.[citation needed]

Knorozov had broad interests in, and contributed to, other investigative fields such as archaeology, semiotics, human migration to the Americas, and the evolution of the mind. However, it is his contributions to the field of Maya studies for which he is best remembered.[citation needed]

In his very last years, Knorozov is also known to have pointed to a place in the United States as the likely location of Chicomoztoc, the ancestral land from which—according to ancient documents and accounts considered mythical by a sizable number of scholars—indigenous peoples now living in Mexico are said to have come.[20]

Knorozov died in Saint Petersburg on March 31, 1999, of pneumonia in the corridors of a city hospital (his daughter Ekaterina Knorozova declares that he died in a regular hospital ward at 6 am, surrounded by the care of his family during his last days), just before he was due to give the Tatiana Proskouriakoff Award Lecture at Harvard University.[citation needed]

List of publications[]

An incomplete listing of Knorozov's papers, conference reports and other publications, divided by subject area and type. Note that several of those listed are re-editions and/or translations of earlier papers.[21]

[]

- Conference papers

- "A brief summary of the studies of the ancient Maya hieroglyphic writing in the Soviet Union". Reports of the Soviet Delegations at the 10th International Congress of Historical Science in Rome ((Authorized English translation) ed.). Moscow: Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1955.

- "Краткие итоги изучения древней письменности майя в Советском Союзе". Proceedings of the International Congress of Historical Sciences (Rome, 1955). Rome. 1956. pp. 343–364.

- "New data on the Maya written language". Proc. 32nd International Congress of Americanists, (Copenhagen, 1956). Copenhagen. 1958. pp. 467–475.

- "La lengua de los textos jeroglíficos mayas". Proceedings of the International Congress of Americanists (33rd session, San José, 1958). San José, Costa Rica. 1959. pp. 573–579.

- "Le Panthéon des anciens Maya". Proceedings of the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences (7th session, Moscow, 1964). Moscow. 1970. pp. 126–232.

- Journal articles

- "Древняя письменность Центральной Америки (Ancient Writings of Central America)". Soviet Ethnography. 3 (2): 100–118. 1952.

- "Письменность древних майя: (опыт расшифровки) (Written Language of the Ancient Maya)". Soviet Ethnography. 1: 94–125. 1955.

- Knorozov, Y. V. (1956). "New data on the Maya written language". Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris. 45: 209–217. doi:10.3406/jsa.1956.961.

- "Estudio de los jeroglíficos mayas en la U.R.S.S. (The Study of Maya hieroglyphics in the USSR)". Khana, Revista municipal de artes y letras (La Paz, Bolivia). 2 (17–18): 183–189. 1958.

- Knorozov, Y. V.; Coe, Sophie D. (1958). "The problem of the study of the Maya hieroglyphic writing". American Antiquity. 23 (3): 284–291. doi:10.2307/276310. JSTOR 276310.

- Knorozov, Youri V.; Alexander, Sidney (1962). "Problem of deciphering Mayan writing". Diogènes (Montreal). 10 (40): 122–128. doi:10.1177/039219216201004007. S2CID 143041913.

- Knorozov, Iu. V. (1963). "Machine decipherment of Maya script". Soviet Anthropology and Archeology. 1 (3): 43–50. doi:10.2753/aae1061-1959010343.

- "Aplicación de las matematicas al estudio lingüistico (Application of mathematics to linguistic studies)". Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico City). 3: 169–185. 1963.

- "Principios para descifrar los escritos mayas. (Principles for deciphering Maya writing)". Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico City). 5: 153–188. 1965.

- "Investigación formal de los textos jeroglíficos mayas. (Formal investigations of Maya hieroglyphic texts)". Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico City). 7: 153–188. 1968.

- "Заметки о календаре майя: 365-дневный год". Soviet Ethnography. 1: 70–80. 1973.

- "Notas sobre el calendario maya; el monumento E de Tres Zapotes". América Latina; Estudios de Científicos Soviéticos. 3: 125–140. 1974.

- "Acerca de las relaciones precolombinas entre América y el Viejo Mundo". América Latina; Estudios de Científicos Soviéticos. 1: 84–98. 1986.

- Books

- La antigua escritura de los pueblos de America Central. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Popular. 1954.

- Система письма древних майя. Moscow: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1955.

- "Сообщение о делах в Юкатане" Диего де Ланда как историко-этнографический источник. Moscow: Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1956. (Knorozov's doctoral dissertation)

- Письменность индейцев майя. Moscow-Leningrad: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1963.

- Tatiana Proskouriakoff, ed. (1967). "The Writing of the Maya Indians". Russian Translation Series 4. Sophie Coe (trans.). Cambridge MA.: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

- Иероглифические рукописи майя. Leningrad: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1975.

- Maya Hieroglyphic Codices. Sophie Coe (trans.). Albany NY.: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies. 1982.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Compendio Xcaret de la escritura jeroglifica maya descifrada por Yuri V. Knorosov". Promotora Xcaret. Mexico City: Universidad de Quintana Roo. 1999.

- Stephen Houston; Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos; David Stuart, eds. (2001). "New data on the Maya written language". The Decipherment of Ancient Maya Writing. Norman OK.: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 144–152.

Others[]

- "Preliminary Report on the Study of the Written Language of Easter Island". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 66 (1): 5–17. 1957. (on the Rongorongo script, with N.A. Butinov)

- Yuri Knorozov, ed. (1965). Predvaritel'noe soobshchenie ob issledovanii protoindiyskih tekstov. Moscow: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. (Collated results of a research team under Knorozov investigating the Harappan script, with the use of computers)

- "Protoindiyskie nadpisi (k probleme deshifrovki)". Sovetskaya Etnografiya. 5 (2): 47–71. 1981. (on the Harappan script of the Indus Valley civilization)

References[]

- ^ See Charles Phillips, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Aztec and Maya (2009).

- ^ Юрий Кнорозов — судьба гения, оказавшегося ненужным советской власти

- ^ The Ukrainian SSR was incorporated as a constituent republic of the Soviet Union on December 30, 1922, barely a month after Knorozov's birth. Among other momentous changes, the Republic was also suffering from the after-effects of the Russian famine of 1921.

- ^ Under the pseudonym "Мари Забель" ("Mary Zabel"). See Ershova (2000, 2002).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ershova (2000)

- ^ MSU's Department of Ethnology was created only the year before, in 1939; see "Department of Ethnology", MSU History Faculty.

- ^ Ershova (2002); Hammond (1999)

- ^ See Ershova (2000) and Kettunen (1998a) for dates of Knorozov's military service. Coe (1992, p.146) gives his unit as the 58th Heavy Artillery, however Ershova (2000) alternatively gives this as the 158th. Ershova also notes Knorozov himself did not participate in the capture of Berlin.

- ^ Quotation is from Kettunen (1998b).

- ^ The incident as relayed in Coe (1992) appears on p.146. For another retelling of this version of the incident, see Gould (1998).

- ^ The work in question was Villacorta and Villacorta's Códices mayas, published 1930 in Guatemala City; see Coe (1992, p.146) and Kettunen (1998a) for the identification of this volume.

- ^ These surviving pre-Columbian codices (screen-fold books) contain a mixture of astronomical, calendric and ritual data, and are illustrated with depictions of deities, animals and other scenes. Crucially, many of the illustrations are also accompanied with captions in the Maya script, which would provide a basis for Knorozov and others to begin in determining the phonetic values represented by the glyphs.

- ^ See record of interview in Kettunen (1998a and 1998b).

- ^ As quoted in Kettunen (1998b).

- ^ Berlin State Library staff (n.d.). "Verlagerte Bestände: Die ausgelagerten Bestände der Staatsbibliothek in Osteuropa". Profil der Bestände (in German). Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Archived from the original on 14 May 2006. Retrieved 1 August 2006.

- ^ Portraits of historians. Time and fate (2004) (Russian: Портреты историков. Время и судьбы. М., Наука, 2004. С.474-491.)

- ^ Named after the noted 19th-century ethnologist and anthropologist Nicholai Miklukho-Maklai.

- ^ Как Юрий Кнорозов разгадал тайну майя, не покидая Ленинграда

- ^ Michael D. Coe. 1992.

- ^ Ferreira (2006, p.6)

- ^ Compiled from Bibliografía Mesoamericana, with additions from Hammond (1999) and Coe (1992).

Sources[]

- Albedil, M.F.; G.G. Ershova; I.K. Federova (1998). "Юрий Валентинович Кнорозов (1922–1999) [Некролог]". Кунсткамера. Этнографические тетради (Kunstkamera. Entograficheskie tetradi) (in Russian). Sankt-Petersburg: Muzey antropologii i etnografii imeni Petra Velikogo (Kunstkamera), and Tsentr “Peterburgskoe vostokovedenie”. 12: 427–428. ISSN 0869-8384. OCLC 28487612. Archived from the original (reproduced online at co-publisher's website, Центр “Петербургское Востоковедение”) on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Bibliografía Mesoamericana (n.d.). "Knorozov, Yuri V. (index of works)". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. Retrieved 1 August 2006.

- Bright, William (1990). Language Variation in South Asia. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506365-1. OCLC 21196637.

- Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (4th edition (revised) ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

- Coe, Michael D. (September–October 1991). "A Triumph of Spirit: How Yuri Knorosov Cracked the Maya Hieroglyphic From Far-Off Leningrad" (online reproduction). Archaeology. New York: Archaeological Institute of America. 44 (5): 39–43. ISSN 0003-8113. OCLC 1481828.

- Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9. OCLC 26605966.

- Coe, Michael D.; Mark van Stone (2005). Reading the Maya Glyphs (2nd ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28553-4. OCLC 60532227.

- Demarest, Arthur (2004). Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Case Studies in Early Societies, No. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59224-0. OCLC 51438896.

- Ershova, Galina G. (2000). "Юрий Валентинович Кнорозов" (reproduced online at Древняя МезоАмерика). Алфавит [Alfavit]. Moscow: Izdatel'skiy dom “Pushkinskaya ploshchad'”. 39. OCLC 234326799. Retrieved 27 July 2006. (in Russian)

- Ershova, Galina G. (26 November 2002). Юрий Кнорозов: Протяните палец, может, дети за него подержатся. Российская газета [Rossiyskaya Gazeta] (in Russian). Moscow: Redaktsiya Rossiyskoy gazety. 224 (3092). ISSN 1606-5484. OCLC 42722022. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Ferreira, Leonardo (2006). Centuries of Silence: The Story of Latin American Journalism. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-98397-0. OCLC 68694080.

- Fischer, Stephen R. (1997). Rongorongo: the Easter Island script: history, traditions, texts. Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, no. 14. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-823710-3. OCLC 37260890.

- Gould, Arthur I. (1998). "Alphabet Soup, Maya-style: A Historical Perspective of the Decipherment of the Written Text of the Ancient Maya Language" (transcript of paper delivered to the Club on April 27, 1998). Chicago Literary Club. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Grube, Nikolai; Matthew Robb (April–June 2000). "Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov (1922-1999)" (Spanish edition of English-language original, Alfredo Vargas González (trans.)). Actualidades Arqueológicas (in Spanish). México, D.F.: Instituto de Investigaciones Arqueologicas-UNAM. 22. OCLC 34202277.

- Hammond, Norman (September 1999). "Yuri Valentinovich Knorosov [obituary]". Antiquity. Cambridge, England: Antiquity Publications. 73 (281): 491–492. ISSN 0003-598X. OCLC 1481624.

- Houston, Stephen D. (1989). Reading the Past: Maya Glyphs. London: British Museum Publications. ISBN 0-7141-8069-6. OCLC 18814390.

- Kettunen, Harri J. (1998a). "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part I". Revista Xaman. Helsinki: Ibero-American Center, Helsinki University. 3/1998. Archived from the original (online publication) on 31 March 2005. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- Kettunen, Harri J. (1998b). "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part II". Revista Xaman. Helsinki: Ibero-American Center, Helsinki University. 5/1998. Archived from the original (online publication) on 31 March 2005. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- Lounsbury, Floyd Glenn (2001) [1984]. "Glyphic Substitutions: Homophonic and Synonymic" (excerpt of pp.167–168,182–183, reproduced from original publication in: J. Justeson and L. Campbell (eds.), Phoneticism in Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing, 1984 [Albany:State University of New York]). In Stephen D. Houston; Oswaldo Fernando Chinchilla Mazariegos; David Stuart (eds.). The Decipherment of Ancient Maya Writing. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 189–193. ISBN 0-8061-3204-3. OCLC 44133070.

- Moran, Gordon, 1998, Silencing Scientists and Scholars in Other Fields, Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

- Nissani, Moti, 1995, The Plight of the Obscure Innovator in Science, Social Studies of Science, 25:165-183, doi=10.1177/030631295025001008.

- Stuart, David (November–December 1999). "The Maya Finally Speak: Decoding the Glyphs Unlocked Secrets of a Mighty Civilization" (reproduced online at latinamericanstudies.org). Scientific American Discovering Archaeology. El Paso, TX: Leach Publishing Group, for Scientific American Inc. 1 (6). ISSN 1538-8638. OCLC 43570694. Retrieved 1 August 2006.

- Tabarev, Andrei V. (September 2007). "The South American Archaeology in the Russian Historiography" (PDF online journal). International Journal of South American Archaeology. Cali, Colombia: Archaeodiversity Research Group Universidad del Valle, and Syllaba Press. 1: 6–12. ISSN 2011-0626.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Yuri Knorozov |

- Works by or about Yuri Knorozov in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Photograph of Y.V. Knorozov, at the Archaeology and Informatics Sector, Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- 1922 births

- 1999 deaths

- 20th-century Mesoamericanists

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Epigraphers

- Historical linguists

- Mayanists

- Recipients of the USSR State Prize

- Mesoamerican epigraphers

- Moscow State University alumni

- Rongorongo

- Russian historians

- Russian Mesoamericanists

- Linguists from Russia

- Soviet historians

- 20th-century historians

- Linguists from the Soviet Union

- 20th-century linguists

- Russian people of Armenian descent

- Soviet military personnel of World War II