Zamzam Well

| Zamzam Well | |

|---|---|

| Native name Arabic: زَمْزَمُ | |

Mouth-piece of the Zamzam Well from the Exhibition of the Two Holy Mosques Architecture Museum[1] | |

| Location | Masjid al-Haram, Mecca |

| Coordinates | 21°25′19.2″N 39°49′33.6″E / 21.422000°N 39.826000°ECoordinates: 21°25′19.2″N 39°49′33.6″E / 21.422000°N 39.826000°E |

| Area | about 30 m (98 ft) deep and 1.08 to 2.66 m (3 ft 7 in to 8 ft 9 in) in |

| Founded | Traditionally c. 2400 BCE |

| Governing body | Government of Saudi Arabia |

Location of Zamzam Well in Mecca, Saudi Arabia | |

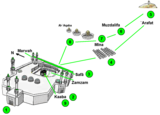

The Zamzam Well (Arabic: بِئْرُ زَمْزَمَ) is a well located within the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 20 m (66 ft) east of the Kaaba,[2] the holiest place in Islam. According to Islam, it is a miraculously generated source of water from Allah, which sprang spontaneously thousands of years ago when Ibrahim's (Abraham's) son ʾIsmaʿil (Ishmael) was left with his mother Hajar (Hagar) in the desert, thirsty and crying. Millions of pilgrims visit the well each year while performing the Hajj or Umrah pilgrimages in order to drink its water.

Etymology[]

The name of the well comes from the phrase Zomë Zomë, meaning "stop flowing", a command repeated by Hajar during her attempt to contain the spring water.[2][dubious ] Alternative spellings include Zam Zam, Zam-Zam, Zemzem, Zem Zem, and Zem-zem.

Traditional origin[]

Islamic tradition states that the Zamzam Well was revealed to Hajar, the second wife of Ibrahim[3] and mother of Ismaʿil.[4] By the instruction of God, Ibrahim left his wife and son at a spot in the desert and walked away. She was desperately seeking water for her infant son, but she could not find any, as Mecca is located in a hot dry valley with few sources of water. Hajar ran seven times back and forth in the scorching heat between the two hills of Safa and Marwah, looking for water. Getting thirstier by the second, the infant Isma'il scraped the land with his feet, where suddenly water sprang out. There are other versions of the story involving God sending his angel, Gabriel (Jibra'il), who kicked the ground with his heel (or wing), and the water rose.[5]

According to Islamic tradition, Ibrahim rebuilt the Baitullah ("House of God") near the site of the well, a building which had been originally constructed by Adam (Adem), and today is called the Kaaba, a building toward which Muslims around the world face in prayer, five times each day. The Zamzam Well is located approximately 20 m (66 ft) east of the Kaaba.[2] In another Islamic tradition, Muhammad's heart was extracted from his body, washed with the water of Zamzam, and then was restored in its original position, after which it was filled with faith and wisdom.[6]

Technical information[]

The Zamzam well was excavated by hand, and is about 30 m (100 ft) deep and 1.08 to 2.66 m (3 ft 7 in to 8 ft 9 in) in diameter. It taps groundwater from the wadi alluvium and some from the bedrock. Originally water from the well was drawn via ropes and buckets, but today the well itself is in a basement room where it can be seen behind glass panels (visitors are not allowed to enter). Electric pumps draw the water, which is available throughout the Masjid al-Haram via water fountains and dispensing containers near the Tawaf area.[2]

Hydrogeologically, the well is in the Wadi Ibrahim (Valley of Abraham). The upper half of the well is in the sandy alluvium of the valley, lined with stone masonry except for the top metre (3 ft) which has a concrete "collar". The lower half is in the bedrock. Between the alluvium and the bedrock is a 1⁄2-metre (1 ft 8 in) section of permeable weathered rock, lined with stone, and it is this section that provides the main water entry into the well. Water in the well comes from absorbed rainfall in the Wadi Ibrahim, as well as run-off from the local hills. Since the area has become more and more settled, water from absorbed rainfall on the Wadi Ibrahim has decreased.

The Saudi Geological Survey has a "Zamzam Studies and Research Centre" which analyses the technical properties of the well in detail. Water levels were monitored by hydrograph, which in more recent times has changed to a digital monitoring system that tracks the water level, electric conductivity, pH, Eh, and temperature. All of this information is made continuously available via the Internet. Other wells throughout the valley have also been established, some with digital recorders, to monitor the response of the local aquifer system.[2]

Zamzam water is colourless and odorless, but has a distinctive taste, with a pH of 7.9– 8, and so is slightly alkaline.[7]

| Mineral concentration as reported by researchers at King Saud University[8] | ||

|---|---|---|

| mineral | concentration | |

| mg/L | oz/cu in | |

| Sodium | 133 | 7.7×10−5 |

| Calcium | 96 | 5.5×10−5 |

| Magnesium | 38.88 | 2.247×10−5 |

| Potassium | 43.3 | 2.50×10−5 |

| Bicarbonate | 195.4 | 0.0001129 |

| Chloride | 163.3 | 9.44×10−5 |

| Fluoride | 0.72 | 4.2×10−7 |

| Nitrate | 124.8 | 7.21×10−5 |

| Sulfate | 124.0 | 7.17×10−5 |

| Total dissolved solids | 835 | 0.000483 |

Safety of Zamzam water[]

The Zamzam Well is tested on a daily basis, in a process involving the taking of three samples from the well, and that these samples are examined in the King Abdullah Zamzam Water Distribution Center in Mecca, which is equipped with advanced facilities.[9]

The Zamzam well was recently renovated in 2018 by the Saudi authority. The project involved sterilisation of the areas around the Zamzam well by removing the debris of concrete and steel used in the old cellar of the Grand Mosque.[10][11][12][13] During Ramadan 100 samples are tested every day to ensure that the water is in good quality.[14]

BBC allegation and response[]

In May 2011, a BBC London investigation stated that water taken from taps connected to the Zamzam Well contained high levels of nitrate, and arsenic at levels three times the legal limit in the UK, the same levels found in illegal water purchased in the UK.[15]

The Saudi authorities rejected BBC's claim and said that the water is fit for human consumption. An official from the Saudi Arabian embassy in London has stated: "Zam Zam water from the Zam Zam well in the Holy City of Makkah, Saudi Arabia, is not contaminated and is fit for human consumption and genuine Zam Zam water does not contain arsenic."[16] The president of the Saudi Geological Survey (SGS), Zuhair Nawab, has stated that the Zamzam Well is tested on a daily basis, in a process involving the taking of three samples from the well, and that these samples are examined in the King Abdullah Zamzam Water Distribution Center in Mecca, which is equipped with advanced facilities. A credible source from the Presidency of the Two Holy Mosques Affairs has also stated that Zamzam water is protected by stainless steel pipes that run to cooling stations and then to the Grand Mosque.[9]

The Council of British Hajjis later declared that drinking Zamzam water was safe, contradicting the BBC report. The council noted that the Government of Saudi Arabia does not allow the export of Zamzam water for resale. They also stated that it was unknown whether the water being sold in the UK was genuine and that people should not buy it and should report the sellers to the Trading Standards if they saw it for sale.[17]

The BBC article concentrated on bottled water supplied by individuals rather than the Presidency of the Two Holy Mosques Affairs, according to Fahd Turkistani, advisor to the General Authority of Meteorology and Environmental Protection. He added that the water provided by the presidency is closely monitored and that ultraviolet rays are used to destroy harmful bacteria. Turkistani has also stated that the Zamzam water pollution may have been caused by unsterilized containers used by illegal workers selling Zamzam water at Makkah gates. The Saudi government has outlawed such illegal Zamzam water sales.[9]

See also[]

- List of reduplicated place names

- Lourdes water, a similarly venerated spring water in Catholicism

Notes[]

- ^ "Exhibition of the Two Holy Mosques' Architecture". . Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Zamzam Studies and Research Centre". Saudi Geological Survey (in Arabic). Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2014.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^ Bible. Genesis 16:3 A Hebrew – English Bible, Retrieved July 13, 2011

- ^ Kazmi, Aftab (May 4, 2011). "UAE residents told to avoid buying Zam Zam water". Gulf News gulfnews.com. Gulf News Broadcasting. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Mahmoud Isma'il Shil and 'Abdur-Rahman 'Abdul-Wahid. "Historic Places: The Well of Zamzam". Archived from the original on February 23, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ "Sahih Muslim Book 001, Hadith Number 0314". .

- ^ Alfadul, Sulaiman M.; Khan, Mujahid A. (October 12, 2011). "Water quality of bottled water in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A comparative study with Riyadh municipal and Zamzam water". Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A. Taylor & Francis. 46 (13): 1519–1528. doi:10.1080/10934529.2011.609109. PMID 21992118. S2CID 21396145.

- ^ Nour Al Zuhair, et al. A comparative study between the chemical composition of potable water and Zamzam water in Saudi Arabia. KSU Faculty Sites, Retrieved August 15, 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Badea Abu Al-Naja (May 7, 2011). Kingdom rejects BBC claim of Zamzam water contamination. Arab News, retrieved June 2, 2014

- ^ "Sacred Zamzam well to go under renovation". Dhaka Tribune. October 30, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Zamzam project to be ready before Ramadan". Saudigazette. February 3, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Zamzam well to be renovated before Ramadan". Arab News. October 30, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "100 samples of Zamzam water tested everyday". Saudigazette. May 19, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "100 samples of Zamzam water tested everyday". Saudi Gazette. May 19, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Lynn, Guy (May 5, 2011). "Contaminated Zam Zam holy water from Mecca sold in the UK". BBC News. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ "'No arsenic in genuine holy water', Saudis say". BBC News. May 8, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ "Zam Zam Water Is Safe, UK". Medical News Today (Press release). Council of British Hajjis (Pilgrims). May 13, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

References[]

- Hawting, G. R. (1980). "The Disappearance and Rediscovery of Zamzam and the 'Well of the Ka'ba'". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 43 (1): 44–54. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00110523. JSTOR 616125.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zamzam Well. |

- Careem, S. H. A. "The Miracle of Zamzam". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on February 2, 2005. Retrieved June 5, 2005. Provides a brief history of the well and some information on the claimed health benefits of Zamzam water.

- Holy wells

- Hajj

- Islamic pilgrimages

- Springs of Saudi Arabia

- Masjid al-Haram

- Abraham