Zaynab bint Ali

Zaynab bint Ali | |

|---|---|

زَيْنَب بِنْت عَلِيّ | |

Arabic text with the name of Zaynab bint Ali | |

| Born | AH 5 (named on) 5 Jumada I (in the ancient (intercalated) Arabic calendar 3 August 626 CE |

| Died | 15 Rajab, AH 62 [aged 57 years] (682 CE)[1][2] Damascus, Umayyad Empire |

| Resting place | Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque, Damascus, the Levant or Al-Sayeda Zainab Mosque, Cairo, Egypt |

| Known for | Leading of the caravan of Al-Husayn after his death at the Battle of Karbala in Iraq, Umayyad Empire |

| Spouse(s) | ‘Abdullah ibn Ja'far |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | |

| Family | House of Muhammad |

Zaynab bint Ali (Arabic: زَيْنَب بِنْت عَلِيّ, Zaynab ibnat ʿAlīy; 3 August 626 – 682), also spelled Zainab, was the daughter of Ali ibn Abi Talib and Fatimah bint Muhammad. The Islamic Prophet Muhammad was her maternal grandfather, and thus she is a member of his Ahl al-Bayt. She is often revered not only for her characteristics and actions, but also for her membership in, and continuation of, the biological line of Muhammad. Like other members of her family, she is considered to be a figure of sacrifice, strength, and piety in both the Sunni and Shia sects of Islam.

Zaynab married ‘Abdullah ibn Ja‘far and had four sons and one daughter with him. When her brother, Husayn, fought against Yazid ibn Mu‘awiyah in 680 CE (AH 61), Zaynab accompanied him. She played an important role in protecting her nephew, ‘Ali ibn Al-Husayn. Zaynab died in 681 CE, and is located in Damascus, Syria.[3]

Early life[]

Zaynab was the third child of Ali ibn Abi Talib and his wife Fatimah, daughter of Muhammad. She was born in Medina in AH 5 (AD 626) on 5 Jumada al-Awwal (3 August Julian calendar).

Like her two elder brothers, Hasan and Husayn ibn Ali, Zaynab was named by Muhammad.[4] The name "Zaynab" means "the adornment of her father". Three of ‘Ali's daughters were in fact named Zaynab, so sometimes this Zaynab was referred to as "Zaynab the Elder".[5] In appearance she resembled both her father and her grandfather.[6]

Fatimah died in 632 when Zaynab was six years old. As per her mother's request, Zaynab took on somewhat of a maternal role to her brothers. As a result, the siblings developed an especially close relationship.[7]

Marriage and family life[]

When Zaynab came of age, she was married to her first cousin ‘Abdullah ibn Ja'far, a nephew of ‘Ali, in a simple ceremony. Although Zaynab's husband was a man of means, the couple is said to have lived a modest life. Much of their wealth was devoted to charity.[8] He maintained a reputation for liberality and patronage in Medina, earning him the nickname “the Ocean of Generosity” (Bahr al jud in Arabic).[9]

The marriage of Zaynab did not diminish her strong attachment to her family. Ali felt a great affection for his daughter and son-in-law, so much so that in 37 AH (657/65/8[2]) when he became caliph and moved the capital from Medina to Kufa, Zaynab and Abdullah moved with him. Zaynab bore four sons – ‘Ali, Aun, Muhammad, and Abbas – and one daughter, Umm Kulthum.[8] It is also believed that she had one more daughter called Umm Abdullah.[10]

Some sources suggest that Zaynab held sessions to help other women study the Quran and learn more about Islam. According to one of her biographies, The Victory of Truth, she started this practice in Medina and later continued it when she moved with her father and family to Kufa.[8]

Battle of Karbala[]

Sometime after the death of the Muawiyah I, Husayn went to Kufa by the invitation of the people of Kufa[11][12] for him to claim the leadership of the Muslim community. Zaynab accompanied him, as did most of his household. By the time Husayn's army arrived, the people of Kufa had changed their minds and betrayed and did not join Husayn's army at the Battle of Karbala.[13]

In many ways, Zaynab functioned as a model of defiance against oppression and other forms of injustice. When her nephew, Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin, was sentenced to death by the governor of Kufah (Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad), she threw herself over him in a protective embrace yelling "By God, I will not let go of him. If you are going to kill him, you will have to kill me along with him."[14][15] Moved by Zaynab's action, the captors spared Zayn al-Abidin's life. Because Zayn al-Abidin was the only one of Husayn's sons to survive the Battle of Karbala, this courageous action was pivotal in preserving the survival of an important part of Ali genetic line and thus the future Imams in Shia Islam.

Zaynab and the other survivors of Husayn's army, most of them women and children, were marched to Damascus, Yazid's capital, where they were held captive. Tradition says that Zaynab, already in anguish due to the death of her brother Husayn and her sons Aun and Muhammad, was forced to march unveiled. This was an extreme indignity to inflict on a high-ranking Muslim woman, the granddaughter of Muhammad.[16][17]

While captive in Damascus, Zaynab held the first majlis, or lamentation assembly in the palace of Yazid to mourn the loss of her beloved brother Husayn.[14]

Another illustration of Zaynab's pious defiance was when a Syrian in Yazid's court demanded that he be given one of the younger captive girls, Fatimah bint Husayn.*[18] Zaynab countered by suggesting that Syrian man was not worthy and did not have that type of authority. When Yazid claimed he had the authority to decide either way, Zaynab issued a scathing retort, answering “You, a commander who has authority, are vilifying unjustly and oppress with your authority."[19]

This comment is representative of a larger sermon attributed to Zaynab in which she condemns Yazid and many of his actions, specifically focusing on his treatment of the household of Muhammad. The sermon is very eloquent and is reminiscent of the work in the Quran's exegesis, Zaynab did with other women in Medina and Kufa. She also made speech in Kufa. The full text of this sermon is linked in the external links section below.[20]

Eventually, Yazid released his captives and allowed them to return to Medina. On the way back, the party stopped once again at Karbala to mourn the loss of Husayn and the others that died there.[14]

Sermon at Yazid's court[]

At the first day of Safar,[21] according to a narration of Turabi, when they arrived at Damascus, they and the heads of fallen ones were taken into Yazid's presence.[22] The identity of each head and killed persons were explained to him. Then he paid attention to an objecting woman. Yazid asked: "Who is this arrogant woman?" The woman rose to answer and said: "Why are you asking them [the women]? Ask me. I will tell you. I am the granddaughter of Muhammad. I am the daughter of Fatimah." People at the court were impressed and amazed by her. At this time, Zaynab gave her khutbah (Arabic: خـطـبـة, sermon).[22]

According to the narration of Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid, in Yazid's presence, a man with red skin asked Yazid to give one of the captured women as a bondwoman.[23][24]

Death[]

The exact date and place of her death are not clear but it is probable that she died in the year 62 AH (681/682[2]) some six months after her return to Medina.[25] Some sources state that she died of illness during a journey with her family from Medina to Syria, at a location known as "Zaynabia".[26][27] Others suggest she was assassinated by Yazid's soldiers while being extradited from Egypt.[28][29]

The anniversary of her death is said to be either the 11th or 21st of Jumada al-Thani, the 24th of Safar, or the 16th of Dhu al-Hijjah. Some suggest that her grave can be found within Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque in Sayyidah Zaynab, Syria. Alternatively, many Sunnis believe her grave can be found within Al-Sayeda Zainab Mosque, a different mosque that is located in Cairo. The Fatimid/Dawoodi Bohra support the claim that Zaynab is buried in Cairo. Their 52nd Dai, Mohammed Burhanuddin, made zarih (a cage-like structure surrounding the tomb) for the shrine in Cairo. The Fatimids and some others believe that the Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque in Damascus is actually the burial site of one of her sisters, Umm Kulthum bint Ali (perhaps caused by confusion between "Sugra" and "Kubra"). There is some historical evidence suggesting Zaynab lived in Cairo near the end of her life.[30]

Ritual mourning[]

From the first days of the month of Muharram up to the tenth day of Ashura, during the mourning custom which includes sermons, reviewing narrations of the Battle of Karbala, not only the death of people who were killed in Karbala is commemorated but also the role of women in battle particularly Zaynab[16] as "transmitter of Husayn ibn Ali's message" is done in Shia towns.[31]

The ritual of majlis, or lamentation assembly mourning the deaths of the Prophetic line, is still practiced as an integral part of Shia Islam.[14]

Historical Impact[]

According to Rawand Osman, during the Battle of Karbala Zaynab is introduced as a woman who stood against cruelty, so this role has been practiced by women in the Iranian Revolution and also in the Lebanon in the last three decades.[31]

Nurse's Day[]

In Iran, her birthday is recognized as Nurse's Day because she nursed children such as Husayn's son Ali among others[19] but also because of her taking care of those wounded in the Battle of Karbala.[19] As Rawand Osman mentioned, Zaynab's caring for Ali, who was among the survivors, shows the unusual role her she took on which went against traditional behavior. In addition to this, the author noted her devotional and political role.[31]

Gallery[]

Til'la e Zaynab: the place where Zaynab watched Al-Husayn ibn ‘Ali at the Battle of Karbala in Iraq

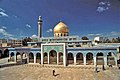

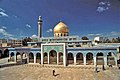

Dome of Zainab, Damascus

The place where Zaynab viewed Battle of Karbala

Zarih Bibi Zainab, Cairo

The Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque in Damascus, Syria

See also[]

- Arba'een

- Sakinah (Fatima al-Kubra) bint Husayn

- Day of Ashura

- Day of Tasu'a

- Sayyidah Nafisah bint Al-Hasan

- Sayyidah Ruqayyah of Cairo

- Al-Tall Al-Zaynabiyya

References[]

- ^ Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya (11 April 2017). "The death anniversary of Sayyida Zainab bint Ali (p)". Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c John Walker (September 2015). "Calendar Converter". Fourmilab. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Esposito, J.L., The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, New York:2003.

- ^ Bilgrami, M. H. (1986). "Chapter One: Angelic Appellation". The Victory of Truth:The Life of Zaynab bint 'Ali. Pakistan: Zahra Publications. ISBN 0-88059-151-X. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Mufīd, Muḥammad Ibn Muḥammad. Kitāb Al-irshād: The Book of Guidance into the Lives of the Twelve Imams. Trans. I.K.A. Howard. Partridge Green, Horsham: Balagha, 1981. Print.

- ^ Shaikh Abbas Borhany, Qazi Dr. (30 June – 6 July 1994), "Syedah Zainab, Protector of the Renaissance of Karbala" (PDF), The Weekly Mag, Pakistan, pp. 5–6

- ^ Bilgrami, M.H (1986). The Victory of Truth – The Life of Zaynab Binte Ali. Karachi, Pakistan: Zahra Publications. p. 82. ISBN 088059-151-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bilgrami, M. H. (1986). "Chapter Three: Womanhood". The Victory of Truth:The Life of Zaynab bint 'Ali. Pakistan: Zahra Publications. ISBN 0-88059-151-X. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Ibn Rashid, Mamar (May 2014). The Expeditions: An Early Biography of Muhammad. NY, USA: New York University Press. p. 316. online ref:[1]

- ^ "Sayyida Zaynab bint 'Ali | Mazarat Misr". Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J. (December 2006). Voices of Islam. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275987329. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Howard, I. K. A. (1990). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 19: The Caliphate of Yazid b. Mu'awiyah A.D. 680-683/A.H. 60–64. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791400401. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Fakhr-Rohani, Muhammad-Reza (December 2012). For the Love of Husayn (AS). MIU press. p. 45. ISBN 9781907905070.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Pinault, David. "Zaynab Bint 'Ali and the Place of the Women of the Households of the First Imams in Shi'ite Devotional Literature." Women in the Medieval Islamic World: Power, Patronage, and Piety. Ed. Gavin Hambly. New York: St. Martin's, 1998. Print.

- ^ Tabari (1990). The History of al-Tabari Volume XIX: The Caliphate of Yazid b. Mu'awiyah. Albanty: State University of New York Press.[page needed]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hyder, Syed Akbar (20 April 2006). Reliving Karbala: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780195345933.

- ^ Kendal, Elizabeth (8 June 2016). After Saturday Comes Sunday: Understanding the Christian Crisis. Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2016. ISBN 9781498239875.

- ^ 4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ṭabarī, Muḥammad Ibn-Ǧarīr Aṭ-. The History of Al-Tabarī: The Caliphate of Yazid B. Mu'awiyah. Trans. I.K.A. Howard. Vol. XIX. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Pr., 1990. Print.[page needed]

- ^ "Sermon of Lady Zaynab in the court of Yazid". al-Islam.

- ^ Qumi, Abbas. Nafasul Mahmum, Relating to the heart-rending tragedy of Karbala. Translated by Aejaz Ali T Bhujwala. Islamic Study Circle.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Syed Akbar Hyder Assistant Professor of Asian Studies and Islamic Studies University of Texas at Austin N.U.S. (23 March 2006). Reliving Karbala: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-19-970662-4.

- ^ Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid. al-Irshad. p. 479.

- ^ "Martyrdom of Imam al-Hussain (Radhi Allah Anhu)". www.ahlus-sunna.com. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ M. H., Bilgrami. "Chapter Nine: Return to Medina". The Victory of Truth: The Life of Zaynab bint 'Ali. Pakistan: Zahra Publications. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Syed Zameer Akhtar Naqvi, Allama Dr. (2012). Princess Zainab-e-Kubra and History of Country Syria (Shahzadi Zainabe Kubra aur Tareekh-e-Mulk-e-Sham) (in Urdu). Karachi, Pakistan: Markz-e-Uloom-e-Islamia (Center for Islamic Studies). pp. 28–49.

- ^ Nisar Ahmed Zainpuri, Akbar Asadi, Mehdi Raza’í (2002). Namoona-e-Sabr (Zainab) translation from Persian to Urdu (in Persian). Qum, Iran: Ansarian Publications. p. 257. ISBN 964-438-399-0.

- ^ "Ziyaarat-e-Shaam" (PDF). Qafilaa-e-Zaa’ireen Houston, Texas & Ali Ali School. March 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Admin (11 October 2014). "Shahadat Majlis of Bibi Zainab(S.A)". Mehfil-e-Murtaza, Karachi, Pakistan. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ "Balaghatun Nisa", by Abul Fazl Ahmad bin Abi Tahir

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Osman, Rawand (3 October 2014). Female Personalities in the Qur'an and Sunna: Examining the Major Sources of ... By Rawand Osman. Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 978-0415839389.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Zaynab bint Ali |

- Zaynab bint Ali in Encyclopedia of Religion

- Speech said to have been given by Zaynab to Yazid

- Islam and women

- Muslim female saints

- Battle of Karbala

- Children of Ali

- Female Sahabah

- 626 births

- 682 deaths

- 7th-century Arabs