Hasan ibn Ali

| Hasan ibn Ali ٱلْحَسَن ٱبْن عَلِي | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

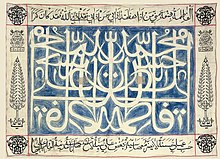

Calligraphic representation of Hasan's name in Rashidun form | |||||

| 5th Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 661–661 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ali | ||||

| Successor | Mu'awiya I (as First Umayyad caliph) | ||||

| 2nd Shia Imam | |||||

| Imamate | 661–670 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ali | ||||

| Successor | Husayn ibn Ali | ||||

| Born | 2 March 625 CE (15 Ramadan AH 3)[2] Medina, Hejaz, Arabian Peninsula | ||||

| Died | 2 April 670 (aged 45) (5 Rabiʽ al-Awwal AH 50)[3] Medina, Umayyad Caliphate (present-day Saudi Arabia) | ||||

| Burial | Al-Baqi', Medina, Saudi Arabia | ||||

| Spouse | show

List | ||||

| Issue | show

List | ||||

| |||||

| Tribe | Banu Hashim (Ahl al-Bayt) | ||||

| Father | Ali | ||||

| Mother | Fatima bint Muhammad | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

| Part of a series on |

| Hasan ibn Ali |

|---|

|

|

| hidePart of a series on Islam Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

| hidePart of a series on |

| Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

Al-Hasan ibn Ali ibn Abi Talib (Arabic: ٱلْحَسَن ٱبْن عَلِيّ ٱبْن أَبِي طَالِب; 2 March 625 – 2 April 670 CE)[22] also spelled Imam Hasan al-Mujtaba (Arabic: ٱلْإِمَام ٱلْحَسَن ٱلْمُجْتَبَىٰ) by Shia Muslims, was the older son of Ali and Fatima, and a grandson of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. He is the second Shi'i Imam after his father, Ali. He is considered to be from the Ahl al-Bayt as well as the Ahl al-Kisa in Shia Islam, and a participant of the event of Mubahala. Muhammad described Hasan and his brother, Husayn, as "the masters of the youth of Paradise." During the caliphate of Ali, Hasan accompanied him in wars. After the assassination of Ali, he was acknowledged caliph.

As soon as the news of Hasan's selection reached Mu'awiya, who had been fighting Ali for the caliphate, he condemned the selection, and declared his decision not to recognize him. Letters exchanged between them before their troops faced each other were to no avail. Hasan sent his vanguard of twelve thousand men to move to Maskin, under Ubayd Allah ibn al-Abbas. There, he was told to hold Mu'awiya's army, until Hasan arrived with the main army. Hasan, however, was facing a problem at Sabat near al-Mada'in, where he gave a sermon. Taking this as a sign that Hasan was preparing to give up battle and make peace with Mu'awiya, some of his troops rebelled against him. Hasan rode off surrounded by his partisans, but was wounded by a Kharijite. The news of the attack, having been spread by Mu'awiya, further demoralized the already discouraged army of Hasan.[23][24] Ubayd Allah, accepted Mu'awiya's bribe and deserted. According to Veccia Vaglieri, 8000 men out of 12000 followed the example of their general. Mu'awiya, who had already started negotiations with Hasan, now sent high-level envoys, while committing himself in a witnessed letter to appoint Hasan his successor,[25][26] along with some other conditions, provided Hasan surrender the reign to him.[27] Thus Hasan abdicated to Mu'awiya, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty to end the First Fitna. For the rest of his life, Hasan retired in Medina, trying to keep aloof from political involvement for or against Mu'awiya, until he died. His wife, Ja'da bint al-Ash'at, is commonly accused of having poisoned him at the instigation of Mu'awiya.[28][29][30][31][32]

Early life[]

Hasan was born on the 15th of Ramadan 3 AH, which corresponds to 2 March 625.[33] He was the son of Ali, the cousin of Muhammad, and Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad, both from the Banu Hashim clan of the Quraysh tribe.[34] Ali wanted to name him "Harb", but Muhammad named him "Hasan".[35][36] He was also called al-Mujtaba (the chosen).[37] To celebrate his birth, Muhammad sacrificed a ram, and Fatima shaved his head and donated the same weight of his hair in silver as alms.[38]

Hasan was brought up in the household of Islamic prophet Muhammad until the age of seven when Muhammad died.[38] The family formed from the marriage of Ali and Fatima was praised many times by Muhammad. In events such as Mubahala and the hadith of the Ahl al-Kisa, Muhammad referred to this family as the ahl al-bayt. In the Qur'an, in many cases, such as the Verse of Purification, the ahl al-bayt has been praised.[c][39] To prove Muhammad's interest in his grandchildren, the Shia cite a hadith in which he called Hasan and Husayn the masters of the youth of paradise. Also when Muhammad took Ali, Fatima, Hasan and Husayn under his cloak and called them ahl al-bayt and stated that they are free from any sin and pollution.[40] Later on, Hasan could remember the prayers Muhammad had taught him, or remembered the occasion when Muhammad prevented him from eating a date which he had already put in his mouth, as it was given as charity (sadaqah) and "partaking of alms was not licit for any member of his family."[41][42] According to Madelung, there are numerous narrations showing Muhammad's love for Hasan and Husayn, such as carrying them on his shoulders, or putting them on his chest and kissing them on the belly. Madelung believes that some of these reports may imply a little preference of Muhammad for Hasan over Husayn, or pointing out that Hasan was more similar to his grandfather.[43]

Event of Mubahala[]

In the year 10 AH (631–632) a Christian envoy from Najran (now in northern Yemen) came to Muhammad to argue which of the two parties erred in its doctrine concerning Jesus. After likening Jesus' miraculous birth to Adam's creation —who was born to neither a mother nor a father— and when the Christians did not accept the Islamic doctrine about Jesus, Muhammad reportedly received a revelation instructing him to call them to Mubahala, where each party should ask God to destroy the false party and their families:[44][45][46]

If anyone dispute with you in this matter [concerning Jesus] after the knowledge which has come to you, say: Come let us call our sons and your sons, our women and your women, ourselves and yourselves, then let us swear an oath and place the curse of God on those who lie.(Qur'an 3:61)[47]

In Shia perspective, in the verse of Mubahala, the phrase "our sons" would refer to Hasan and Husayn, "our women" refers to Fatima, and "ourselves" refers to Ali. Most of the Sunni narrations quoted by al-Tabari do not name the participants. Other Sunni historians mention Muhammad, Fatima, Hasan and Husayn as having participated in the Mubahala, and some agree with the Shia tradition that Ali was among them.[48][49][46]

Life during the Rashidun Caliphate[]

During Caliphate of Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman[]

After Muhammad's death, Hasan and his brother took no part in important events of the Caliphate of the first three Caliphs, except for following their father in opposing some deeds of the third Caliph, Uthman;[50] such as defending Abu Dharr al-Ghifari who had preached against some misdeeds of powerful, and was going to be exiled from Medina.[51] During the Caliphate of Uthman, Hasan reportedly refused his father's suggestion to apply legal punishment of forty lashes on Uthman's half brother, Al-Walid ibn Uqba, who was accused of drinking alcohol. Ali rebuked Hasan for not doing it and asked his nephew, Abd Allah ibn Ja'far to carry out the flogging.[52] According to several narrations, Ali asked Hasan and Husayn to defend the Caliph and carry water to him. According to Veccia Vaglieri, when Hasan entered Uthman's house, Uthman was already assassinated.[53] According to al-Baladhuri, Hasan was wounded a little while defending Uthman. It is also said that he criticized his father for not defending Uthman more forcefully.[54]

During the Caliphate of Ali[]

Hasan reportedly was against his father's policy of fighting with his opponents as he believed that these wars would cause division in the Muslim community.[55] Before the Battle of Camel, Hasan was sent to Kufa along with Ammar ibn Yasir to collect force for Ali's army,[56] and was able to provide an army of six to seven thousand.[57] Based on Hasan's participation in Ali's battles at Camel and Siffin, his role in raising up support, and his communication with Mu'awiya later during his own caliphate, where he asserted the right of Muhammad's family to the caliphal office, the Shi'a historian Rasul Jafarian has suggested that the notion of Hasan opposing Ali's policies is incorrect.[58] In 658 AD, Ali made Hasan responsible for his land endowments.[59]

Caliphate[]

After Ali's assassination by the Kharijite Abd al-Rahman ibn Muljam in retaliation for Ali's attack on the Kharijites at Nahrawan, the people gave allegiance to Hasan.[60] According to Moojan Momen most of the surviving companions of Muhammad (Muhajirun and Ansar) were in the army of Ali at the time, so they must have been in Kufa and must have been pledged their allegiance to him. Since there is no report of opposition.[61] In his inaugural speech at the Grand Mosque of Kufa, Hasan praised the merits of his family, quoting verses of the Qur'an on the matter:

I am of the Family of the Prophet from whom God has removed filth and whom He has purified, whose love He has made obligatory in His Book when He said: Whosoever performs a good act, We shall increase the good in it. [Qur'an 42:23] Performing a good act is love for us, the Family of the Prophet.[62]

Qays ibn Sa'd, a staunch supporter of Ali and a trusted commander of his army, was the first to give allegiance to him. Qays then stipulated the condition that the pledge of allegiance, should be based on the Qur'an, the sunnah (Deeds, Sayings, etc.) of Muhammad, and on the pursuit of a jihad against those who declared lawful (halal) that which was unlawful (haram). Hasan, however, tried to avoid the last condition by saying that it was implicitly included in the first two,[63][64] as if he knew, as Jafri put it, from the very beginning of the Iraqis' lack of resolution in time of trials, and thus Hasan wanted to "avoid commitment to an extreme stand which might lead to complete disaster".[63] According to al-Baladhuri, the oath taken by Hasan stipulated that people "should make war on those who were at war with Hasan, and should live in peace with those who were at peace with him." This condition made people astonished, asking themselves: if Hasan is talking about peace, is it because he want to make peace with Mu'awiya?[65][66]

Dispute with Mu'awiya[]

As soon as the news of Hasan's selection reached Mu'awiya, who had been fighting Ali for the caliphate, he condemned the selection, and declared his decision not to recognise him. Letters exchanged between Hasan and Mu'awiya before their troops faced each other were to no avail.[67][68] As negotiations had stalled, Mu'awiya summoned all the commanders of his forces in Syria[69] and began preparations for war. Soon, he marched his army of sixty thousand men through Mesopotamia to Maskin, about 50 kilometers north of modern-day Baghdad. Meanwhile, he attempted to negotiate with Hasan through letters, asking him to give up his claim.[70]

These letters provided arguments concerning the rights of caliphate which would lead to the origin of the Shia Islam. In one of his long letters to Mu'awiya in which Hasan summoned him to pledge allegiance to him, Hasan made use of the argument of his father, Ali, which the latter had advanced against Abu Bakr after the death of Muhammad. Ali had said; If the Quraysh could claim leadership of the Ansar because Muhammad belonged to the Quraysh, his family members, who were closest to him in every way, would be more qualified to lead the community.[71] Mu'awiya, while recognising the excellence of Muhammad's family, further asserted that he would willingly follow Hasan's request were it not for his own superior experience in governing:[72][73]

…You are asking me to settle the matter peacefully and surrender, but the situation concerning you and me today is like the one between you [your family] and Abu Bakr after the death of the Prophet … I have a longer period of reign [probably referring to his governorship], and I am more experienced, better in policies, and older in age than you … If you enter into obedience to me now, you will accede to the caliphate after me.[74]

According to Jafri, Mu'awiya hoped to either force Hasan to come to terms, or attack the Iraqi forces before they had time to strengthen their location. However, Jafri says, Mu'awiya believed that, even if Hasan was defeated and killed, he was still a threat, for, another member of the clan of Hashim could simply claim to be his successor. Should he abdicate in favor of Mu'awiya, however, such claims would have no weight and Mu'awiya's position would be guaranteed.[75]

Mobilization of troops and subsequent mutiny[]

As the news of Mu'awiya's army reached Hasan, he ordered his local governors to mobilize, then addressed the people of Kufa: God had prescribed the jihad for his creation and called it a loathsome duty (Kurh, Qur'an 2:216).[76] There was no response at first, as, according to Madelung, some tribal chiefs, paid by Mu'awiya, were reluctant to move. Hasan's companions scolded them, asking whether they wouldn't answer to the son of Muhammad's daughter. Turning to Hasan, they assured him of their obedience, and immediately left for the war camp. Hasan admired them and later joined them at Nukhayla (an army mustering ground outside Kufa), where people were coming together in large groups.[77] Hasan appointed Ubayd Allah ibn al-Abbas (or Abd Allah ibn Abbas[78]) as the commander of his vanguard of twelve thousand men to move to Maskin. There he was told to hold Mu'awiya until Hasan arrived with the main army. He was advised not to fight unless attacked, and that he should consult with Qays ibn Sa'd, who was appointed as second in command.[79][80][81][82] According to Madelung, the choice of Ubayd Allah ibn al-Abbas, who had previously surrendered Yemen, the province under his rule, to Mu'awiya's forces without war, and was admonished by Ali for it, indicates that Hasan was hoping to reach a peaceful conclusion.[83]

While his vanguard was waiting for his arrival at Maskin, Hasan himself faced mutiny at his camp near al-Mada'in. He stated in his speech that he bore no resentment, hatred, or evil intentions towards anyone, that "whatever they hated in community was better than what they loved in schism",[84][79] Taking this as a sign that he intended to make peace with Mu'awiya, some of the troops rebelled, looting his tent,[85][86] and seizing the prayer rug from underneath him. While his loyalists were escorting him to safety in al-Mada'in, a Kharijite named al-Jarrah ibn Sinan ambushed and wounded Hasan in thigh, accusing him of unbelief like "his father before him". The attacker was eventually overpowered and killed, and Hasan was cared for by his governor of al-Mada'in, Sa'd ibn Mas'ud al-Thaqafi.[84][87][88] The news of this attack, having been spread by Mu'awiya, further demoralised Hasan's army, and led to extensive desertions.[23][89][90]

Hasan's vanguard at Al-Maskin[]

When the Kufans vanguard reached al-Maskin, they realized that Mu'awiya had already arrived. Mu'awiya sent a representative to tell them that he had received letters from Hasan requesting a ceasefire. He urged the Kufans not to attack until the talks are over. Mu'awiya's claim was maybe false, but he had good reason to think that he could make Hasan surrender.[91][92] The Kufans, however, insulted Mu'awiya's envoy. Then, Mu'awiya sent the envoy to visit Ubayd Allah in private, and to swear to him that Hasan had requested a truce from Mu'awiya, and offered Ubayd Allah 1,000,000 dirhams, half to be paid at once, the other half in Kufa, provided he switched sides. Ubayd Allah accepted and deserted at night to Mu'awiya's camp. Mu'awiya was extremely pleased and fulfilled his promise to him.[31][91][93]

The next morning, Qays ibn Sa'd took charge of Hasan's troops and, in his sermon, severely denounced Ubayd Allah, his father and his brother. Believing that the desertion of Ubayd Allah had broken the spirit of his enemy, Mu'awiya sent Busr with an armed force to force their surrender. Qays, however, attacked and drove him back. The next day Busr attacked with a larger force but was repulsed again.[94] Mu'awiya then sent a letter to Qays offering bribes but Qays refused.[95][93] As the news of the riot against Hasan and of his having been wounded arrived, however, both sides abstained from fighting to wait for further news.[96] According to Vaglieri, Iraqis had no wish to fight and each day a group of them joined Mu'awiya.[97] It seems that 8000 men out of 12000, followed the example of their general, Ubayd Allah, and joined Mu'awiya.[93][98]

Treaty with Mu'awiya[]

Mu'awiya, who had already started negotiations with Hasan, now sent high-level envoys, appealing to spare the blood of community of Muhammad, by a peace treaty according which Hasan would be the caliph after Mua'wiya and he would be given whatever he wished. Hasan accepted the overture in principle and sent Amr ibn Salima al-Hamdani al-Arhabi and his own brother-in-law Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath al-Kindi back to Mu'awiya as his negotiators, along with Mu'awiya's envoys. Mu'awiya then wrote a letter saying that he was making peace with Hasan, who would become caliph after him. He swore that he would not seek to harm him, and that he would give him 1,000,000 dirhams from the treasury (bayt al-mal) annually, along with the land tax of Fasa and Darabjird, which Hasan was to send his own tax agents to collect. The letter was witnessed by the four envoys and dated in August 661.[25][99]

When Hasan read the letter, he commented that Mu'awiya sought "to appeal to his greed for something which he, if he desired it, would not surrender to him."[38] Then he sent Mu'awiya's nephew, Abd Allah ibn al-Harith, to Mu'awiya, instructing him: "Go to your uncle and tell him: If you grant safety to the people I shall pledge allegiance to you." Afterward, Mu'awiya gave him a blank paper with his seal at the bottom, inviting Hasan to write on it whatever he desired. Hasan wrote that he would make peace and hand over power to Mu'awiya, provided that Mu'awiya acted in accordance with the Book of God, the Sunna of His Prophet, and the conduct of the rightly guided caliphs. He clarified that Mu'awiya should not appoint a successor, but there should be an electoral council. And people will be safe wherever they were.[25][100] The letter was witnessed by Abd Allah ibn Harith and Amr ibn Salima and transferred by them to Mu'awiya to be aware of its contents and to confirm it.[101] After concluding the agreement, Hasan returned to Kufa, where Qays joined him.[102] According to Jafri, the conditions according which Hasan resigned, are reported in sources not only with big variation, but with ambiguity and confusion. Historians like Ya'qubi and al-Masudi do not mention the terms of the agreement at all. Tabari mentions four conditions which goes as followed:[103] Hasan would retain five million dirhams then in the treasury of Kufa; he would be permitted to gain the annual revenue of the Persian district Darabjird; his father, Ali, would not be cursed;[103][104] and that Ali's friends and followers should be given amnesty.[d] The first condition makes no sense to Jafri, as Kufa's treasury was already in Hasan's possession, besides there was not such amount of money in Kufa's treasury, as Ali used to distribute it every week, and his sudden death and expenses of the Hasan's war did not make it better. Dinawari recorded different conditions: The people of Iraq should not be maltreated; the annual revenue of Ahwaz should be given to Hasan, and the Hashimites should be preferred over Umayyadds in granting pensions and awards. Other historians like ibn Abd al-Barr and ibn al-Athir add some other conditions such as: No one from people of Medina, Hijaz and Iraq would deprived from what they had possessed during Ali's caliphate; and that caliphate should be passed to Hasan after Mu'awiya. Abu al-Faraj mentions only the last two conditions recorded by Tabari.[105] Veccia Vaglieri, while discussing different conditions, doubts the accuracy of them, as, she believes, they are so variant that "it is impossible to correct and reconcile."[106] The most comprehensive account, which explains the different ambiguous accounts of other sources, according to Jafri, is given by Ahmad ibn A'tham, which he must have taken from al-Mada'ini. Because ibn A'tham recorded the terms in two parts: The first part[e] was prescribed by Hasan's representative, Abd Allah ibn Nawfal, who was sent to Maskin to negotiate with Mu'awiya, and the second part[f], which Hasan himself dictated it when the blank sheet was brought to him. If the two sets of conditions are combined, they would encompass all the scattered conditions found in other above mentioned sources.[100] Madelung's view is close to that of Jafri when he stipulates that Hasan abdicated on the condition that Mu'awiya act conforming to the Qur'an, the Sunna and the conduct of the rightly guided caliphs,[g] every one should be safe and Mu'awiya would not have the right to appoint the next caliph.[38]

Abdication and retirement in Medina[]

After the peace treaty with Hasan, Mu'awiya set out with his troops to Kufa where in public surrender ceremony, he asked Hasan to stand up and apologize. After first refuting, Hasan rose and reminded the people that he and Husayn were the only grandsons of Muhammad, and that he had surrendered the reign to Mu'awiya "in the best interest of the community":[110] Hasan declared:[111][112]

O people, surely it was God who led you by the first of us and Who has spared you bloodshed by the last of us. I have made peace with Mu'awiya, and "I know not whether haply this be not for your trial, and that ye may enjoy yourselves for a time. [Qur'an 21:111]" [111]

In his own speech Mu'awiya denied all his previous promises to Hassan and others, which were made solely to stop the revolt.[113] According to another account, Mu'awiya told them that the reason why he had fought them was not to make them pray, fast, perform the pilgrimage, and give alms, considering that they had been already doing those, but to be their Amir (Commander or Leader), and God had bestowed that upon him against their will.[h][114] Then he shouted:

God's protection is dissolved from anyone who does not come forth and pledge allegiance. Surely, I have sought revenge for the blood of Uthman, may God kill his murderers, and have returned the reign to those to whom it belongs in spite of the rancour of some people. We grant respite of three nights. Whoever has not pledged allegiance by then will have no protection and no pardon.[115]

Then people rushed from every direction to vow allegiance.[116] While still camping outside Kufa, Mu'awiya faced a Kharijite revolt.[117] He sent a cavalry troop against them, but they were beaten back. Mu'awiya then sent after Hasan, who had already left for Medina, and commanded him to return and fight against the Kharijites. Hasan, who had reached al-Qadisiyya, wrote back that he gave up the fight against Mu'awiya, although it was his legal right, for the sake of peace and compromise in the Community, not for fighting in his side.[118][119]

In the nine-year period between Hasan's abdication in 41 AH (661 CE) and his death in 50 AH (670 CE), Hasan retired in Medina,[120] trying to keep aloof from political involvement for or against Mu'awiya. In spite of that, however, he was considered the chief of Muhammad's household, by the Banu Hashim themselves and the partisans of Ali, who pinned their hopes on his final succession to Mu'awiya.[121] Occasionally, Shias, mostly from Kufa, went to Hasan in small groups, and asked him to be their leader, a request to which he declined to respond, as he had signed a peace treaty with Mu'awiya.[122][123] Madelung has quoted Al-Baladhuri,[i] as saying that Hasan, on the basis of his peace terms with Mu'awiya, sent his tax collectors to Fasa and Darabjird. The caliph had, however, instructed Abd Allah ibn Amir, now governor of Basra, to incite the Basrans to protest that this money belonged to them by right of their conquest, and they chased Hasan's tax collectors out of the two provinces. According to Madelung, however, that Hasan would send tax collectors from Medina to Iran, after just having made plain that he would not join Mu'awiya in fighting the Kharijites, is entirely incredible.[124] When Mu'awiya found out that Hasan would not help his government, relations between them became worse.[38]

Death and burial[]

Hasan died on the 5th of Rabi al-Awwal 50 AH (2 April 670 CE).[125] Several early sources report that he was poisoned by his wife, Ja'da bint al-Ash'ath.[j][k][127][128][28] According to Veccia Vaglieri, Hasan died either from a long-term illness, or from poisoning. Mu'awiya is said to have suborned her with the promise of a large sum of money, as well as the promise of her marriage to Yazid.[129] Al-Tabari, however, has not reported this, which had led Madelung to believe that al-Tabari suppressed it out of concern for the faith of the common people.[130][128] Hasan is said to have refused to name his suspect to Husayn, for fear that the wrong person would be killed in revenge.[131] He was 38 years old when he abdicated the reign to Mu'awiya, who was 58 years old at the time. This difference in age, according to Jafri, indicates a serious obstacle for Mu'awiya, who wanted to nominate his son, Yazid, as his heir-apparent. This was unlikely, Jafri writes, due to the terms on which Hasan had abdicated to Mu'awiya; and considering the big difference in age, Mu'awiya would not have hoped that Hasan would naturally die before him.[28] Hence, according to Jafri, as well as Madelung and Momen, Mu'awiya would naturally be suspected of having a hand in a killing that removed an obstacle to the succession of his son Yazid.[132][126]

The burial of Hasan's body near that of Muhammad, was another problem which could have led to bloodshed. Hasan had instructed his brothers to bury him near his grandfather, but that if they feared evil, then they were to bury him in the cemetery of al-Baqi. The Umayyad governor, Sa'id ibn al-'As, did not interfere, but Marwan swore that he would not permit Hasan to be buried near Muhammad with Abu Bakr and Umar, while Uthman was buried in the cemetery of al-Baqi. Banu Hashim and Banu Umayya were on the verge of a fight, with their supporters brandishing their weapons. At this point, Abu Hurayra , who was on the side of Banu Hashim, despite having previously served Mu'awiya on a mission to ask for the surrender of the killers of Uthman,[133] tried to reason with Marwan, telling him how Muhammad had highly regarded Hasan and Husayn.[134] Nevertheless, Marwan, who was a cousin of Uthman, was unconvinced,[135] but Aisha, while sitting on a mule decided not to permit Hasan to be buried near his grandfather, and said the burial place was part of the property she lived in.[136] Ibn Abbas, condemned Aisha by saying "What mischief you bring about, one day on a mule and one day on a camel!" referring to her sitting on a camel in a war against Hasan's father at the battle of the Camel.[137] Her refusal to allow Hasan to be buried next to his grandfather, despite allowing her father, Abu Bakr, and Umar to be buried there, offended the supporters of Ali.[138]

Then Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya reminded Husayn that Hasan made the matter conditional by saying "unless you fear evil."[130] The body was then carried to the cemetery of al-Baqi.[139] Marwan joined the carriers, and, when questioned about it, said that he gave his respect to a man "whose ḥilm [forbearance] weighed mountains."[140] Husayn led the funeral prayer.[141] Hassan's tomb was later turned into a shrine and a dome was built on it. Later on, it was destroyed by the Wahhabis twice; once in 1806 and the other time in 1927.[l][142]

Contemporary forensic evidence for the mystery of Hasan's death[]

In 2016, Burke et al, published an original research article based on the medieval documents. Using mineralogical, medical, and chemical facts, they suggested that mineral calomel (mercury(I) chloride, Hg2Cl2), originating from the Byzantine Empire, was the substance primarily responsible for the murder of Hasan. According to this research, the "forensic hypothesis is consistent with the historical position, reflected in ancient (medieval) documents," that Hasan was poisoned by his wife, Ja'da, at the instigation of Mu'awiya and with the participation of the Byzantine emperor.[143]

Family life[]

It is said that Hasan spent most of his youth in "making and unmaking marriages", so that "these easy morals gained him the title "the divorcer" (miṭlāq) which involved Ali in serious enmities."[144] According to Madelung "stories and anecdotes expanded on this theme and have led to absurd suggestions that he had 70 or 90 wives in his lifetime", along with a harem of 300 concubines.[145] Matthew pierce believes that these accusations was proposed by later Sunni writers, although they were not able to name more than sixteen names.[146] Most of narrations of this type are narrated by al-Mada'ini which Madelung believes in most cases are vague, lacking in names, and traceable details. They seem to be "spun out of the reputation of Hasan as a miṭlāq, now interpreted as a habitual and prodigious divorcer, some clearly with a defamatory intent".[147] The number ninety, first spread by Muhammad al-Kalbi and was picked up by al-Mada'ini, however, according to Madelung, al-Mada'ini was not able to name a single name more than the eleven he mentioned, five of which must be considered as "uncertain or highly doubtful".[148] Veccia Vaglieri writes that these marriages does not seems to have aroused much censure.[149] According to Madelung, narrations that quote Ali as warning Kufans not to give their daughter in marriag to Hasan "deserve no credit".[150] Living in his father's household, Madelung writes, "Ḥasan was in no position to enter into any marriages not arranged or approved by him".[151] He believes that most of Hasan's marriages had a political intent in favor of his father, because he gave his nickname, "Abu Muhammad", to his first son from his first wife (Ḵawla bint Manẓur) he freely chose after Ali's death, and wanted to make him his primary heir, however, when Muhammad died, he chose Kawla's second son, Ḥasan, for this purpose.[152]

Wives and children[]

The number of Hasan's wives and children are mentioned differently: According to ibn Saa'd, whose account, according to Madelung, is the most reliable, Hasan had 15 sons and 9 daughters from six wives and three named concubines;[153] Medelung describes the historical order of Hasan's marriages as follows, according which Hasan's marriage to six women is provable: Ja'da bint al-Ash'at, Umm Bashir, Khawla bint Manzur ibn Zabban, Hafsa bint Abd al-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr, Umm Ishaq bint Talha and Hind bint Suhayl ibn Amr.[154] His first marriage was to Ja'da bint al-Ash'at, which happened soon after Ali's arrival to Kufa. Ja'da was the daughter of the Kinda chief, al-Ash'ath ibn Qays. According to Madelung, by this marriage, Ali wanted to establish ties with the powerful Yemeni tribal coalition in Kufa. Hasan had no child from this wife. Ja'da is commonly accused of poisoning Hasan.[155] Umm Bashir was Hasan's second wife. She was the daughter of Abu Mas'ud Uqba ibn Amr, who was among those who apposed Kufan's revolt against Uthman. According to Madelung, Ali was hoping to draw him to his side by this marriage.[m][156] After Hasan abdicated and settled in Medina, he married Khawla bint Manzur ibn Zabban, daughter of the Fazara chief Manzur ibn Zabban. Previously she had been married to Muhammad ibn Talha, who was killed in the Battle of Camel, and had two sons and a daughter from him. Hasan surrendered her to her father who protested that "he was not someone to be ignored with respect to his daughter".[n] She bore Hasan, his son Hasan.[157] Hafsa bint Abd al-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr, the daughter of Abd al-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr, was another wife of Hasan, who married her in Medina. Al-Mundhir ibn al-Zubayr was in love with her and spread false rumors about her, which made Hasan divorce her. Thus, Hasan in this context is described as mitlaq, meaning the one who is "ready to divorce on insubstantial grounds."[o][158] Umm Ishaq bint Talha, the daughter of Talha, was also among Hasan's wives. She was described as extremely beautiful but of bad character. Mu'awiya proposed her marriage to his son, Yazid, when he met her brother, Ishaq ibn Talha, in Damascus, however Ishaq, returning to Madina, gave her to Hasan, which made Mu'wiya to give her up. Hasan had a son from her, namely Talha, who died childless.[p][159] Hind bint Suhayl ibn Amr, the daughter of Suhayl ibn Amr, was another wife of Hasan. She had been married to al-Rahman ibn Attab, who was killed in the Battle of Camel, then married to Abd Allah ibn Amir, who divorced her. Thus Hasan was her third husband.[q] Hasan had no child with Hind.[160]

Hasan's other children, according to Madelung, are probably from concubines: Amr ibn Hasan (married and had three children); al-Qasim and Abu Bakr (both childless and killed in the Battle of Karbala); Abd al-Rahman (childless); al-Husayn; and Abd Allah who might be the same as Abu Bakr. Late sources add three other names: Isma'il, Hamza and Ya'qub, none of whom have had children. Hasan's daughters from slave women were: Umm Abd Allah who married Zayn al-Abidin and Muhammad al-Baqir, the fifth Shai Imam, was born from her;[161] Fatima (not known to have married); Umm Salama (childless); and Ruqayya (not known to have married).[162]

Appearance and morality[]

Hasan is described as a personage who most closely resembled his grandfather, Muhammad. He is sometimes described as good orator, although, according to Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, he had a defect in his speech, inherited from one of his uncles. He is also described as forbearing (halim), generous and pious (made many pilgrimages on foot).[163] Hasan named two of his sons, Muhammad, after his grandfather, which, according to Madelung, shows that he patterned his self-image after Muhammad, rather Ali.[164] According to Vaglieri, "love of peace, distaste for politics and its dissensions, the desire to avoid widespread bloodshed", could be accepted as motivations for Hasan's abdication, however he has been criticized by some of his followers who believed Hasan have humiliated Muslims by giving in to Mu'awiya. According to Vaglieri, the hadith: "This my son is a lord by means of whom God will one day reunite two great factions of Muslims", which is narrated from Muhammad, accordingly could be purported to justify Hasan's lack of resistance as a merit.[165]

According to Momen, among Shia Imams, no one has been criticized by western historians as vigorously as Hasan. He has been accused of being "uxorious, unintelligent, incapable and lover of luxury"; also for giving in to Mu'awiay without fight.[166] According to Madelung, Hasan's readiness to divorce, which brought about the title "the divorcer" for him, cannot be viewed as an "inordinate appetite for sexual diversion". Madelung makes some examples to show that Hasan comes across as "endowed with both a concern for dignified propriety and a spirit of forbearing conciliatoriness, an important aspect of the hilm [forbearance] of the true sayyid."[167] For instant, Hasan divorced Hafsa, the grand daughter of Abu Bakr, when she was accused by al-Mundhir [r] out of a sense of "propriety", although he still loved her. But when al-Mundhir married her and it became revealed that the accusations were false, Hasan visited the couple, but quickly forgave al-Mundhir, as he recognized that his rival had lied out of his love for Hafsa. Hasan showed his continuous affection for Hafsa by visiting her in a proper company of her nephew.[168]

Having returning Khawla bint Manzur to her father[s], while her father had no right over her (since she had other marriages previously); his readiness to divorce Hind bint Suhayl when he saw signs of a renewed love in her previous husband; advising his younger brother, Husayn, to marry Umm Ishaq bint Talha after he died; are also considered as the signs Hasan's affection for others regardless of their mistreatment.[169] Madelung believes that he dealt with his wives, as with others, like a "noble and forbearing (ḥalim) Arab sayyed."[170] When he was poisoned, he refused to reveal the suspect to his brother, Husayn.[171]

Beliefs[]

In Qur'an[]

The verse of Mubahala was revealed before the event of Mubahalah, according to which Qur'an instructed (See: [1]) Muhammad to engage in Mubahalah (mutual cursing) with the Christians who did not accept Islamic doctorin (concerning Jesus)[172] by "referring the matter to God and calling down God's curse on whomever was the liar." The contest was set for the next day, when people were witness Muhammad came out with only Ali, Faitma, Hasan and Husayn, who stood under his cloak, after which Muhammad, Ali, Fatima, Hasan and Husayn became famous as the Family of the Cloak.[173] Thus the title, the Family of the Cloak, is related sometimes to the Event of Mubahala.[t].[174]

The Christians asked him why he had not brought the leader of his religion; so he replied he was instructed by God to do so.[175] The verse "God wishes only to remove taint from you, people of the Household, and to make you utterly pure." is also attributed to this event.[u] The context in which the Verse of Purification revealed, according to Shia exegetes, refers only to Ali, Fatima and their descendants, who are also referred to as the People of the Household.[176]

In hadiths[]

There are many narrations showing the respect of Muhammad toward his grandsons, including the statements that his two grandsons "will be the Sayyids (chiefs)[177] of the young in Paradise" [v][178][179] or according to Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai, the Shia scholar, they were Imams, "whether they stand up or sit down",[w][180][38][181] and "He who has loved Hasan and Husayn, has loved me and he who has hated them has hated me."[182][183] Muhammad also reportedly predicted that Hasan would make peace between two factions of Muslims.[184] He also declared that Hasan along with his brother Husayn, and his parents (Ali and Fatima), were the People of the House, free from all impurity. Both Sunnis and Shias also testify that Muhammad showed his affection towards Hasan in word and action, such as when he descended from the pulpit to pick up Hasan who had stumbled and fallen down.[185][186] It is narrated from Muahammad that while taking Hasan and Husay's hands, commented "whoever who loves me and loves these two and loves their mother and father, will be with me in my station on the Day of Resurrection."[x][187] Muhammad would let Hasan and Husayn to climb on his back while he was prostrating in his prayer.[188]

Views of Islamic religions[]

Both Shi'a and Sunni Muslims consider Hasan to belong to the ahl al-bayt of Muhammad, as one of the ahl al-kisa ("People of the Cloak") and a participant of the event of Mubahala.[189]

Concerning Hasan's abdication, the historian Maria Massi Dakake writes that the sources that are hostile to Hasan, depict his peace treaty with Mu'awiya as a sign of his weakness and state that Hasan had intended to surrender from the very beginning and that sending his troop was just a show of resistance.[190] More favorable reports reject this interpretation arguing that Hasan's abdication was the result of Kufans' mutiny,[191][192][193] just as they previously pushed Ali into accepting arbitration, and that Hasan wanted unity and peace within the Muslim community as a hadith by Muhammad had predicted that.[194]

Sunnis[]

According to some Sunnis, such as Bukhari, he is the fifth and the last rightly guided caliph,[y][184] and was known for his forbearance.[195][196] A group of Sunnis cite a hadith of Muhammad, which states that the caliphate after him would last for thirty years, in support of this view as the term of Hasan as caliph completed the thirty years after Muhammad's death. Accordingly, Hasan has been considered one of the Rashidun caliphs by a group of Sunni scholars.[z][139]

Shias[]

According to Shia sources, shortly after the migration to Medina, Muhammad told Ali that God had commanded him to give his daughter, Fatima, in marriage to him.[197] Hasan is regarded by all Shia as the second infallible Imam, who was designated by his father, Ali, to succeed him in the position.[198] According to Shia, theirs was the only house that archangel Gabriel allowed to have a door to the courtyard of The Prophet's Mosque.[184] According to Vaglieri, Hasan's abdication, being criticized by his followers, did not affects his position as Imam, as he renounced the caliphate because of his detachment from worldly matters.[199]

Imamate[]

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

| Twelvers |

|---|

|

|

According to Donaldson, there was not a significant difference between the idea of imamate, or divine right, exemplified by each Imam designating his successor, and other ideas of succession at first.[200] According to an accepted Shia tradition recorded by Kulayni, before Ali died, he gave Hasan the (secret) books and his armor, in presence of his family (the people of the household) and the shia leaders, and said:

O my son, the Apostle has commanded me to give you the designation, and to bequeath to you the secret books and the armour, in the same way that he gave them to me. And when you die you are to give them to your brother Husain... [201]

According to Momen, Ali had apparently failed to nominate a successor before he died; however, on several occasions, he reportedly expressed his idea that "only the Prophet's Bayt were entitled to rule the Community", and Hasan, whom he had appointed his inheritor, must have been the obvious choice, as he would eventually be chosen by people to be the next caliph.[202][203] It is narrated that Ali called Hasan waliu'l amr, in the sense that Ali gave him the authority to command; also called him Waliu'l dam; for, it was left to Hasan's judgment, as to whether he should avenge ALi's blood.[204]

Sunnis, on the other hand, reject the doctrine of Imamate on the basis of their interpretation of verse 33:40 of the Qur'an which says that Muhammad, as the seal of the Prophets, "is not the father of any of your men"; and that is why God let Muhammad's sons die in infancy.[aa] This is why Muhammad did not nominate a successor, as he wanted to leave the succession to be resolved "by the Muslim Community on the basis of the Qur’anic principle of consultation (shura)".[205] The question Madelung proposes here is why the family members of Muhammad should not inherit aspects of Muhammad's character, apart from prophethood, such as rule (hukm), wisdom (hikma), and leadership (imama). Since the Sunni concept of the "true caliphate" itself defines it as a "succession of the Prophet in every respect except his prophethood", Madelung further asks, "If God really wanted to indicate that he should not be succeeded by any of his family, why did He not let his grandsons and other kin die like his sons?"[205]

Miracles[]

According to Donaldson, compared to other Shia Imams, a smaller number of miracles is attributed to Hasan, a position rejected by Vaglieri. Some of these miracles are as follows: At the time of his birth, Hasan recited the Qur'an and praised God; he made an old tree to produce ripe dates; he asked God to send food to 70 passengers, and the food did not diminish; and he resurrected a dead man.[206][207]

Bibliography[]

Among the works dedicated to the life of Hasan Mojtaba are the works entitled Maqātil al-Ṭālibīyīn, which are historical-biographical compilation concerning the descendants of Abu Talib, who died under the following circumstances: being killed, poisoned to death in a treacherous way, on the run from the rulers’ persecution, or confined until death. Maqātil al-Ṭālibīyīn by Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani is among these works.[208][209]

See also[]

- Fourteen Infallibles

- Muawiya, Hassan and Hussein (TV series)

Notes[]

- ^ English: The Chosen

- ^ English: Commander of the Faithful

- ^ For more information see:Hasan ibn Ali#In Qur'an

- ^ This fourth condition is mentioned indirectly in a different context.[103]

- ^

- "that the caliphate will be restored to Hasan after the death of Mu'awiya;

- that Hasan will receive five million dirhams annually from the state treasury;

- that Hasan will receive the annual revenue of Darabjird;

- that the people will be guaranteed peace with one another."[107]

- ^

- "that Mu'awiya should rule according to the Book of God, the Sunna of the Prophet, and the conduct of the righteous caliphs;

- that Mu'awiya will not appoint or nominate anyone to the caliphate after him, but the choice will be left to the shura of the Muslims;

- that the people will be left in peace wherever they are in the land of God;

- that the companions and the followers of Ali, their lives, properties, their women, and their children, will be guaranteed safe conduct and peace. This is a solemn agreement and covenant in the name of God, binding Mu'awiya b. Abi Sufyan to keep it and fulfil it;

- that no harm or dangerous act, secretly or openly, will be done to Hasan b. Ali, his brother Husayn, or to anyone from the family of the Prophet (Ahl Bayt an-Nabi); this agreement is witnessed by Abd Allah b. Nawfal, 'Umar b. Abi Salama, and so and so."[108]

- ^ This condition, according to Jafri, might have been added later in "an attempt at reconciliation of the Jama'a", since Ali's supporters always insisted on following only the Sunna of the Prophet and refused to acknowledge the validity of the Sunna of the first three caliphs.[109]

- ^ See also Ibn Abi l-Hadld, Shark, XVI, 15; Abu al-Faraj, Maqdtil, 70.[114]

- ^ Al-Baladhuri, Ansab, III, 47.

- ^ See also Mas'oodi, Vol 2: Page 47, Tāreekh - Abul Fidā Vol 1 : Page 182, Iqdul Fareed - Ibn Abd Rabbāh Vol 2, Page 11, Rawzatul Manazir - Ibne Shahnah Vol 2, Page 133, Tāreekhul Khamees, Husayn Dayarbakri Vol 2, Page 238, Akbarut Tiwal - Dinawari Pg 400, Mawātilat Talibeyeen - Abul Faraj Isfahāni, Isti'ab - Ibne Abdul Birr.

- ^ These reports are also accepted by the major Sunnite historians al-Waqidi, al-Mada'ini, Umar ibn Shabba, al-Baladhuri and Haytham ibn Adi.[126]

- ^ In the eyes of Wahabis, historical sites and shrines encourage shirk – the sin of idolatry or polytheism – and should be destroyed. See (Taylor, Jerome (24 September 2011). "Mecca for the rich: Islam's holiest site 'turning into Vegas'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2017.)

- ^ Afterwards Ali appointed him as the governor of Kufa, during the time when himself was involved in the Battle of Siffin. Hasan had two or three children from Umm Bashir. His eldest son, Zayd, his daughter Umm al-Husayn, and probably another daughter named Umm al-Hasan. See (Madelung 1997, p. 381)

- ^ According to Madelung she either have been given in marriage to Hasan by Abd Allah ibn Zubayr, who was married to her sister, or Khawla herself have been given the choice to Hasan to Marry her. Upon hearing this, her father, said "he was not someone to be ignored with respect to his daughter". He came to Medina and protested, so Hasan surrendered her to him, and he took him away to Quba. Khawla reproached her father, reminding him of Muhammad's saying: "Al-Hasan b. Ali will be the lord of the youth among the inmates of paradise." He told her: "Wait here, if the man is in need of you, he will join us here." Then Hasan joined them along with some of his relatives and took her back and married her, this time with her father's consent. See (Madelung 1997, pp. 381–382)

- ^ After that, Asim, the son of Umar, married her. Al-Mundhir this time accused her before Asim, who also divorced her. Then Al-Mundhir proposed marriage to her, but Hafsa did not accept. Later on she was persuaded to marry him, since it was the only way to prove that the rumors were false and were originated from Al-Mundhir's love for her. See (Madelung 1997, p. 382)

- ^ In spite of her alleged bad character Hasan was satisfied with her and asked his younger brother, Husayn, to marry her after his death. Husayn did so and had a daughter, named Fatima, from her. See (Madelung 1997, p. 383)

- ^ Later on, Hind commented on her three husband as saying: "The lord (sayyid) of all of them was al-Hasan; the most generous of them was Ibn 'Amir; and the one dearest to me was 'Abd al-Rahman b.'Attab". See (Madelung 1997, pp. 383–384)

- ^ For more information see Hasan ibn Ali#In Medina

- ^ For more information see Hasan ibn Ali#In Medina

- ^ see L. Massignon, La Mubahala de Médine et l’hyperdulie de Fatima, Paris, 1935; idem, “Mubāhala,” EI1, supplement, p. 150

- ^ "see, for example, ṢaḥīḥMoslem, English tr. by A. H. Siddiqui, Lahore, 1975, IV, pp. 1293-94"

- ^ Although its authenticity was disputed by Marwan ibn Hakam

- ^ Allusion to whether they occupy the external function of caliphate or not. See also Irshad, p. 181; Ithbat al-hudat, vol. V, pp. 129 and 134.

- ^ See also:Tirmidhi, Sunan, Vol.2, p.301

- ^ Hasan remained caliph for six months, and it is mentioned in the History of the Caliphs by Al-Suyuti that Muhammad had predicted that "The caliphate after me will be for thirty years." Thus, according to al-Bukhari, since Muhammad died in the year 11 A.H., and Hasan abdicated in the year 40 A.H., Hasan was Muhammad's rightly successor[184]

- ^ See Al-Suyuti, Tarikh al-Kulifa, P. 191; al-Bukhari, 53/9; Al-Tirmidhi, 46/30; in which narrated from Muhammad who took little Hasan with him into the pulpit and said people: "Verily this son of mine is a prince, and perchance the Lord will unite through his means the two contending parties of the Muslims."[139]

- ^ See Goldziher, Muhammedanische Studien, II, 105-6; Y. Friedmann, 'Finality of Prophethood in Sunni Islam', JSAI, 7 (1986), 177-215, at 187-9.[205]

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 26

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Pierce 2016, p. 135

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jafri 1979, p. 145.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Madelung 1997, p. 322

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 27

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jafri 1979, p. 158.

- ^ Madelung 1997

- ^ Tabåatabåa'åi, Muhammad Husayn (1981). A Shi'ite Anthology. Selected and with a Foreword by Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i; Translated with Explanatory Notes by William Chittick; Under the Direction of and with an Introduction by Hossein Nasr. State University of New York Press. p. 137. ISBN 9780585078182.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lalani, Arzina R. (9 March 2001). Early Shi'i Thought: The Teachings of Imam Muhammad Al-Baqir. I. B. Tauris. p. 4. ISBN 978-1860644344.

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 26-28

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Poonawala & Kohlberg 1985

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 240

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 26

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Madelung 2003.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 14–15

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 240

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 15–16

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 14

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bar-Asher, Meir M.; Kofsky, Aryeh (2002). The Nusayri-Alawi Religion: An Enquiry into Its Theology and Liturgy. Brill. p. 141. ISBN 978-9004125520.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 15–16

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 16

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 14

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 240

- ^ Vaglieri 1960, p. 382

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Jafarian 1378, pp. 252-253

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 26-27

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 311–312

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jafri 1979, p. 133.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Dakake 2008, p. 74

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986

- ^ Lammens. "al-Ḥasan". = Encyclopaedia of Islam. doi:10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_SIM_2728. ISBN 9789004082656.

- ^ Article "AL-SHĀM" by C.E. Bosworth, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume 9 (1997), p. 261.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 317

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 135.

- ^ Jafri 1979, pp. 135-136.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 27

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 136.

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 134.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 317

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 318

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 104-112.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Madelung 1997, p. 318

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 142.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986

- ^ Ibn Rashid, Mamar (1709). The Expeditions: An Early Biography of Muhammad. Library of Arabic Literature. ISBN 9780814769638. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donaldson 1933, p. 69.

- ^ Dakake 2008, p. 74

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 319

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 241

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 106-107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Madelung 1997, p. 320

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 146.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wellhausen 1927, p. 106.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 321

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 321

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 322

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, pp. 241-242

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, pp. 241-242

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 27

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jafri 1979, pp. 150-152.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 323

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 153.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jafri 1979, p. 149.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 105.

- ^ Jafri 1979, pp. 149-153.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, pp. 241-242

- ^ Jafri 1979, pp. 150-151.

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 151.

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 152.

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donaldson 1933, p. 71.

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 154.

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b Madelung 1997, p. 325

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 324

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 324

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 324–325

- ^ Jafri 1979, pp. 157-158.

- ^ Netton, Ian Richard (2007). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Routledge. ISBN 978-0700715886.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 27-28

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 157.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 328

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b Madelung 1997, p. 331.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 28

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donaldson 1933, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 242

- ^ Jump up to: a b Madelung 1997, p. 332

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 242

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 28

- ^ Madelung, Wilferd (1998). The Succession to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9780521646963.

- ^ Madelung 1997

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 332

- ^ Pierce 2016, p. 80

- ^ Pierce 2016, p. 80

- ^ Madelung 1997

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Donaldson 1933, p. 78.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 332–333

- ^ Halevi, Leor (2011). Muhammad's Grave: Death Rites and the Making of Islamic Society. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231137430.

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Burke, Nicole; Golas, Mitchell; Raafat, Cyrus L.; Mousavi, Aliyar (July 2016). "A forensic hypothesis for the mystery of al-Hasan's death in the 7th century: Mercury(I) chloride intoxication". Medicine, Science and the Law. 56 (3): 167–171. doi:10.1177/0025802415601456. ISSN 0025-8024. PMC 4923806. PMID 26377933.

- ^ Donaldson 1933, p. 74.

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Pierce 2016, p. 84

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 385

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 386-387

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 242

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 385

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 380–384

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 380

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 381

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 381–382

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 382

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 383

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 383–384

- ^ Pierce 2016, p. 135

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 384–385

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 240

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 242

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 27

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 385

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 385

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 385

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 242

- ^ Algar 1984

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 14

- ^ Algar 1984

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 14

- ^ Algar 1984

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 26

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 240

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 26

- ^ Tabatabai, Sayyid Muhammad Husayn (1997). Shi'ite Islam. Translated by Seyyed Hossein Nasr. SUNY press. pp. 65, 172–173. ISBN 978-0-87395-272-9.

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 26

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 26

- ^ Pierce 2016, p. 70

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Donaldson 1933, p. 73.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 240

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 26

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 15

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 240

- ^ Momen 1985, p. 14

- ^ Dakake 2008, pp. 74-75

- ^ Dakake 2008, pp. 74-75

- ^ Jafri 1979, p. 144.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 107.

- ^ Dakake 2008, pp. 74-75

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 385

- ^ Madelung 2003

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 243

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 243

- ^ Donaldson 1933, p. 66

- ^ Donaldson 1933, pp. 67-68

- ^ Momen 1985, pp. 14, 26-28

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986

- ^ Donaldson 1933, p. 68

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Madelung 1997, p. 17

- ^ Donaldson 1933, pp. 74-75.

- ^ Veccia Vaglieri 1986, p. 243

- ^ Bahramian 1992, p. 734–735.

- ^ Günther 1994, p. 200–205.

Sources[]

- Jafri, S. M. (1979). Origins and Early Development of Shi'a Islam. London and New York: Longman. ISBN 9780582780804.

- Dakake, Maria Massi (2008). Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (ed.). The Charismatic Community: Shi'ite Identity in Early Islam. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7033-6.

- Pierce, Matthew (2016). Twelve Infallible Men: The Imams and the Making of Shi’ism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674737075.

- Algar, .H (1984). "Āl–e ʿAbā". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64696-3.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2003). "ḤASAN B. ʿALI B. ABI ṬĀLEB". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 November 2013.

- Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03531-5.

- Poonawala, Ismail; Kohlberg, Etan (1985). "ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭāleb". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. 1. New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press. pp. 838–848.

- Veccia Vaglieri, Laura (1986). "(al-)Ḥasan b. ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 3. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 240–243.

- Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. Burleigh Press. pp. 66–78.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia (1960). "ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 381–386. OCLC 495469456.

- Jafarian, Rasul (1378). Tarikh-e Siasi-e Eslam (in Persian). 2. Oom: Daftar-e Nashr-e al-Hadi. ISBN 964-400-107-9.

- Bahramian, Ali (1992). "Maqātil al-Ṭālibīyīn". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica (1 ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISSN 1875-9823. OCLC 225873940.

- Günther, Sebastian (1994). "Maqâtil Literature in Medieval Islam". Journal of Arabic Literature. 25 (3): 192–212. doi:10.1163/157006494x00103. ISSN 0085-2376.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.

External links[]

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Hasan and Hosein". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Hasan and Hosein". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- 624 births

- 670 deaths

- Rashidun caliphs

- Family of Muhammad

- Arab Muslims

- 7th-century Muslims

- Shia imams

- Ismaili imams

- Muslim martyrs

- Sahabah martyrs

- People of the Quran

- 7th-century caliphs

- 7th-century imams

- Children of Ali

- Assassinated Shia imams

- Twelver imams

- Zaidi imams

- Deaths by poisoning

- Assassinated caliphs

- Philanthropists

- Burials at Jannat al-Baqī