Zhoubi Suanjing

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (May 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

The Zhoubi Suanjing (Chinese: 周髀算經; Wade–Giles: Chou Pi Suan Ching) is one of the oldest Chinese mathematical texts. "Zhou" refers to the ancient Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE); "Bi" means thigh and according to the book, it refers to the gnomon of the sundial. The book is dedicated to astronomical observation and calculation. "Suan Jing" or "classic of arithmetics" were appended in later time to honor the achievement of the book in mathematics.

This book dates from the period of the Zhou dynasty, yet its compilation and addition of materials continued into the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE). It is an anonymous collection of 246 problems encountered by the Duke of Zhou and his astronomer and mathematician, Shang Gao. Each question has stated their numerical answer and corresponding arithmetic algorithm.

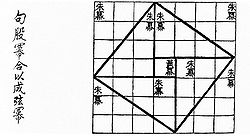

The book also makes use of the Pythagorean Theorem on various occasions[1] and might also contain a geometric proof of the theorem for the case of the 3-4-5 triangle [2] (but the procedure works for a general right triangle as well). Zhao Shuang (3rd century CE) added a commentary to the text, and also included the diagram depicted on this page, which seems to correspond to the geometric figure alluded to in the original text .[3]

There is some disagreement among historians whether the text actually constitutes a proof of the theorem.[2] This is in part because the famous diagram was not included in the original text and the description in the original text is subject to some interpretation (see the different translations of Chemla 2005 and Cullen 1996, p. 82).

Other commentators such as Liu Hui (263 CE), Zu Gengzhi (early sixth century), Li Chunfeng (602–670 CE) and Yang Hui (1270 CE) have expanded on this text.

Background behind Pythagorean derivation[]

At this early point in Chinese history the model of the ancient Chinese equivalent of Heaven, 天 Tian, was symbolized as a circle and the earth was symbolized as a square. In order to make this concept easily understood the adopted symbol of the heavens was the ancient Chinese chariot. The charioteer would stand in the square body of the vehicle and a "canopy", the equivalent of an umbrella, stood next to them. The world was thus likened to the chariot in that the earth, the square, was where the charioteer stood, and heaven, the circle, was suspended above them. The concept has thus been termed "Canopy Heaven", 蓋天 (Gaitian).[4]

Eventually the populace began to turn away from the "Canopy Heaven" concept in favor of the concept termed "Spherical Heaven", 渾天 (Huntian). This was partly due to the fact that the people were having trouble accepting heaven's encompassment of the earth in the fashion of a chariot canopy because the corners of the chariot were themselves relatively uncovered.[5] In contrast, "Spherical Heaven", Huntian, has Heaven, Tian, completely surrounding and containing the Earth and was therefore more appealing. Despite this switch in popularity, supporters of the Gaitian "Canopy Heaven" model continued to delve into the planar relationship between the circle and square as they were significant in symbology. In their investigation of the geometric relationship between circles circumscribed by squares and squares circumscribed by circles the author of the Zhoubi Suanjing deduced one instance of what today is known as the Pythagorean Theorem.[6]

See also[]

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Cullen (1996), p. 82.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chemla (2005), p. [page needed].

- ^ Cullen (1996), p. 208.

- ^ Tseng (2011), pp. 45–49.

- ^ Tseng (2011), p. 50.

- ^ Tseng (2011), p. 51.

Works Cited[]

- Chemla, Karine (2005). Geometrical Figures and Generality in Ancient China and Beyond. Science in Context. ISBN 0-521-55089-0.

- Cullen, Christopher (1996). Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55089-0.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

- Tseng, Lillian Lan-ying (2011). Picturing Heaven In Early China. Harvard East Asian Monographs (1st ed.). Cambridge: The Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-06069-2.

External links[]

- Full text of the Zhoubi Suanjing, including diagrams - Chinese Text Project.

- Full text of the Zhoubi Suanjing, at Project Gutenberg

- Christopher Cullen. Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China: The 'Zhou Bi Suan Jing', Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0521035376

- Chinese classic texts

- Chinese mathematics

- Han dynasty texts

- Mathematics manuscripts

- Zhou dynasty texts