Noldor

| Noldor | |

|---|---|

| Also known as | High Elves, Deep Elves, Tatyar |

| Information | |

| Created date | First Age |

| Created by fictional being | Eru Ilúvatar |

| Home world | Middle-earth |

| Language | Quenya |

| Leader | Kings of the Noldor |

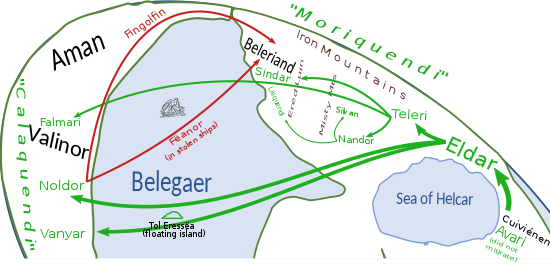

In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Noldor (also spelled Ñoldor, meaning those with knowledge in Quenya) are a kindred of High Elves who initially migrated to Valinor from Middle-earth and lived in Eldamar, the coastal region of Aman, a continent that lay west of Middle-earth. The majority of the Noldor returned to Middle-earth following the murder of their first leader Finwë by the Dark Lord Morgoth, on the instigation of Finwë's eldest son Fëanor. They were the second clan of the Elves in both order and size, the other clans being the Vanyar and the Teleri.

Among the Elven people, the Noldor showed the greatest talents for intellectual pursuits, technical skills and physical strength, yet are prone to unchecked ambition and prideful behaviour. They typically have grey eyes and dark hair, though divergent physical features could be found among some individuals. Several Noldorin characters play a pivotal role in the development and lore of Tolkien's major works, in particular The Lord of the Rings, as well as the posthumously published The Silmarillion.

Etymology[]

"Noldor" meant those who have great knowledge and understanding. The Noldor are called Golodhrim or Gódhellim in Sindarin, and Goldui by Teleri of Tol Eressëa. The singular form of the Quenya noun is Noldo and the adjective is Noldorin, which is also the name of their dialect of Quenya.[T 1]

Tolkien gave some Noldorin leaders like Finwë and Fingolfin their own heraldic devices, carefully distinguishing their ranks by the number of points touching the rim.[1]

Attributes[]

Culture[]

The Noldor are counted among the Calaquendi ("Elves of the Light") or High Elves, as they have seen the light of the Two Trees of Valinor.[2] The most distinctive aspect of Noldorin culture is their fondness for craftwork and skill of their workmanship, which ranged from lapidary to embroidery to the craft of language. Among the Elven kindreds, the Noldor are the most beloved by the Vala Aulë, who originally taught them craftsmanship. As a result of their renown as the most skilled of all peoples in lore, warfare and crafts, the Noldor are sometimes called the "Deep Elves". Following their return to Middle-earth during the First Age, the Noldor built great cities within their realms in the land of Beleriand, such as Nargothrond and Gondolin.[T 2]

The Noldor primarily spoke Quenya as their first language, though the Exiles in Middle-earth would also speak Sindarin, a Quenya term for the language of the Sindar ("grey people" in Quenya), a kindred of Elves who initially accepted the summons of the Valar but never completed the journey to Valinor, and remained in Middle-earth as a prominent civilization. Among the wisest of the Noldor was Rúmil, creator of the first writing system and author of many epic books of lore.[3] Fëanor, son of Finwë and Míriel, was the greatest of their craftsmen, "mightiest in skill of word and of hand",[T 3] and creator of the Silmarils. Fëanor also devised an improved version of Rúmil's script.[3]

The Noldor are considered to be the proudest of the Elves as they take great pride in their abilities: by the words of the Sindar, "they needed room to quarrel in".[T 4] On the other hand, the negative aspect of their pride sometimes manifests as an arrogance that plagued the Noldor and later caused them great suffering.[T 1]

Physical appearance[]

The Noldor are tall and physically strong. Their hair colour is usually a very dark shade of brown; Tolkien hesitated over whether their hair might be black.[T 5][T 6] Red and even white ("silver") hair occasionally exist among some individuals. Their eyes were usually grey or dark, with the inner light of Valinor reflected in their eyes referenced by the Sindarin term Lachend, which translates as "flame-eyed".[T 4] Intertribal marriages with the Teleri and Vanyar are common, which introduce into some Noldorin bloodlines physical features which are not commonly associated with their people. For example, the Noldo prince Glorfindel is noted to have blond hair, as does Galadriel, a descendant of Indis of the Vanyar, second wife of Finwë known for her golden blonde hair.

Fictional history[]

Early history[]

According to Elven-lore, the Noldor as a clan was founded by Tata, the second Elf to awake at Cuiviénen, his spouse Tatië and their 54 companions. The fate of Tata and Tatië is not recorded; it was Finwë who led the Noldor to Valinor, where he became their King, and their chief dwelling-place was the city of Tirion upon Túna. In Valinor "great became their knowledge and their skill; yet even greater was their thirst for more knowledge, and in many things they soon surpassed their teachers. They were changeful in speech, for they had great love of words, and sought ever to find names more fit for all things they knew or imagined."[T 3]

The Noldor drew the ire of the rogue Vala Melkor, who envied their prosperity and, most of all, the Silmarils crafted by Fëanor. So he went often among them, offering advice, and the Noldor listened, being eager for knowledge. But Melkor sowed lies, and in the end the peace in Tirion was poisoned. Fëanor, having assaulted Fingolfin his half-brother and thus broken the laws of the Valar, was banished to his fortress Formenos, and with him went Finwë his father. Fingolfin remained as the ruler of the Noldor of Tirion.

With the aid of the spider spirit Ungoliant, Melkor destroyed the Two Trees of Valinor, slew Finwë, stole the Silmarils and departed from Aman. Driven by vengeance, Fëanor rebelled against the Valar and roused the Noldor to leave Valinor, follow Melkor to Middle-earth and wage war against him for the recovery of the Silmarils. Though the greater part of the Noldor still held Fingolfin as the rightful leader, they followed Fëanor out of kinship and to avenge Finwë. Fëanor and his sons swore a terrible oath of vengeance against Melkor, whom Fëanor renamed Moriñgotto or Moriñgotho (later translated into Sindarin as Morgoth), or anyone who comes into possession of the Silmaril.[T 7]

Flight of the Noldor: exile to Middle-earth[]

In Alqualondë, the Noldor hosts led by Fëanor demanded that the Teleri let them use their ships. When the Teleri refused, Fëanor's forces took the ships by force, committing the first Kinslaying. A messenger from the Valar came later and delivered the Prophecy of the North, pronouncing the Doom of Mandos on the Noldor for the Kinslaying and warned that a grim fate awaits the Noldor should they proceed with their rebellion. Some of the Noldor who had no hand in the Kinslaying, including Finarfin son of Finwë and Indis, returned to Valinor, and the Valar forgave them. The majority of the Noldor, some of whom were blameless in the Kinslaying, remained determined to leave Valinor for Middle-earth. Among them were Finarfin's children, Finrod and Galadriel, who chose to follow Fingolfin instead of Fëanor and his sons.[T 8]

The Noldor led by Fëanor crossed the sea to Middle-earth, leaving those led by Fingolfin, his half-brother, behind. Upon his arrival in Middle-earth, Fëanor had the ships burned. When the Noldor led by Fingolfin discovered their betrayal, they went farther north and crossed the sea at the Grinding Ice or the Helcaraxë. Suffering substantial losses along the way, this greatly added to the animosity they had for Fëanor and his sons.[T 8] The deaths of the Two Trees and the departure of the Noldor out of the Undying Lands marked the end of the Years of the Trees, and the beginning of the Years of the Sun, when the Valar created the Moon and the Sun out of Telperion's last flower and Laurelin's last fruit. Fëanor's company was soon attacked by Morgoth in an event known as the Battle under Stars or Dagor-nuin-Giliath. Fëanor himself was mortally wounded by several Balrogs, who had issued forth from Angband and captured his eldest son Maedhros.

Fingon, the eldest son of Fingolfin, later saved Maedhros from captivity, which settled the rift between their houses for a time. Maedhros was due to succeed Fëanor, but he regretted his part in the Kinslaying as well as the abandonment of Fingolfin, and left the leadership of the Noldor in Middle-earth to his uncle Fingolfin, who became the first High King of the Noldor. The rest of his brothers dissented and began to refer to themselves as the Dispossessed, paying little deference to Fingolfin or his successors, and were still determined to fulfill the oath they swore to recover the Silmarils on behalf of their father.

In Beleriand, in the north-west of Middle-earth, the Noldor made alliances with the Sindar, and later with Men of the Three Houses of the Edain. Fingolfin reigned long in the land of Hithlum, and his younger son Turgon built the hidden city of Gondolin. The Sons of Fëanor ruled the lands in Eastern Beleriand, while Finrod Finarfin's son was the King of Nargothrond and his brothers Angrod and Aegnor held Dorthonion. Fingolfin's reign was marked by warfare against Morgoth and in the year 60 of the First Age after their victory in Dagor Aglareb the Noldor started the Siege of Angband, the great fortress of Morgoth. In the year 455 the Siege was broken by Morgoth in the Dagor Bragollach, or Battle of Sudden Flame, in which the north-eastern Elvish realms were conquered, with the exception of Maedhros' fortress at Himring. Fingolfin in despair rode to Angband and challenged Morgoth to single combat, dealing the Dark Lord seven wounds before perishing. Fingolfin is succeeded by his eldest son Fingon the Valiant, who became the second High King of the Noldor in Beleriand.

In the year 472, Maedhros organised an all-out attack on Morgoth, which led to the Nírnaeth Arnoediad, the Battle of Unnumbered Tears. However, the Noldor and their allies were utterly defeated when they are betrayed by the Easterlings and surrounded by Morgoth's forces. Fingon was slain by Gothmog, and is succeeded by his brother Turgon. Morgoth scattered the remaining forces led by the Sons of Fëanor, and in 495 Nargothrond was also conquered. Turgon had withdrawn to Gondolin which was kept hidden from both Morgoth and other Elves, though his realm was later betrayed to Morgoth by his nephew Maeglin in 510. Turgon died during the Fall of Gondolin, though his daughter Idril led many of his people to their escape and found their way south. Gil-galad, son of Orodreth, succeeded Turgon and became the fourth and last High King of the Noldor in Middle-earth.

Between the years 545–583 the War of Wrath was fought between Morgoth and the host of the Valar. As the result of the cataclysmic destruction from the war, Beleriand sank into the sea, except for a part of Ossiriand later known as Lindon, and a few isles. The defeat of Morgoth marked the end of the First Age and the start of the Second, and most of the Noldor would return to Aman, though some like Galadriel or Celebrimbor, grandson of Fëanor, refused the pardon of the Valar and remained in Middle-earth.

Second and Third Ages[]

Gil-galad founded a new kingdom at Lindon and ruled throughout the Second Age, longer than any of the High Kings before him. After Sauron re-emerged and manipulated Celebrimbor and the smiths of Eregion to forge the Rings of Power, he fortified Mordor and began the long war with the remaining Elves of Middle-earth. His forces attacked Eregion, destroying it, but were repelled in Rivendell and Lindon. With the aid of the Númenóreans, the Noldor managed to defeat him for a time.

In the year 3319 of the Second Age Númenor fell due to Ar-Pharazôn's rebellion against the Valar, manipulated in part by Sauron, though Elendil escaped to the mainland with his sons Anárion and Isildur, who established the realms of Arnor and Gondor. Gil-galad set out for Mordor in the Last Alliance of Elves and Men with Elendil's forces and defeated Sauron in the Siege of Barad-dûr, though Gil-galad himself perished with no successors as High King of the Noldor. Among the lineal descendants of Finwë in Middle-earth, only Galadriel and individuals who are part of the Half-elven bloodline remained.

In the Third Age, the Noldor in Middle-earth dwindled, and by the end of the Third Age the remaining Noldorin communities left in Middle-earth had begun preparations for their permanent departure to the Undying Lands. For example, in The Fellowship of the Ring a band of Elves led by Gildor Inglorion from the House of Finrod are encountered by Frodo and his fellow Hobbits while on their journey to the Grey Havens.[4] Following the War of the Ring in the Fourth Age, the Noldor had all but returned to Valinor.

Kings[]

In Valinor the Noldorin monarch was simply titled King of the Noldor:[T 3][T 9] the title High King (as applied to Elves in Valinor) was reserved for Ingwë, the Vanyar monarch.[T 3] The Noldorin monarchs in Middle-earth assumed the title High King. The list of the monarchs of the Noldor are as follows:

- In Valinor:

- Finwë, first King of the Noldor.

- Fëanor, eldest son of Finwë.[T 10] when his father died he claimed the title of King, although a significant number of Noldor disapproved of him as their leader.[T 9]

- Finarfin, third son of Finwë, ruler of the residual Noldor in Aman.

- In Middle-earth:

- Fingolfin, second son of Finwë, first High King of the Noldor in exile.

- Fingon, eldest son of Fingolfin.

- Turgon, second son of Fingolfin.

- Gil-galad, great-grandson of Finarfin,[a] the last High King of the Noldor in exile.

Fëanor was nominally monarch of the exiled Noldor for a brief period of time until he was killed in the conclusion of Dagor-nuin-Giliath; his eldest son Maedhros was captured at the same time, and leadership of the Noldor was not resolved until his rescue. Fingolfin became the undisputed leader of the Noldor upon Maedhros' renunciation of his leadership claim.[T 8] The Noldor had many princely houses besides that of Finwë: Glorfindel of Gondolin and Gwindor of Nargothrond, while not related to Finwë, were princes in their own right. These lesser houses held no realms, as all the Noldorin realms of Beleriand and later Eriador were ruled by direct descendants of Finwë.

The Mannish descendants of Elros, the Kings of Arnor, later used the title of High King, although there is no indication that this referred to anything other than kingship over the Dúnedain.

Galadriel, the last of the House of Finwë in Middle-earth (other than the Half-elven) and Gil-galad's cousin, never claimed a royal title for herself. After the Second Age, the only known Elven Kingdom in Middle-earth was the Silvan realm of Mirkwood, ruled by Thranduil of the Sindar.[4]

House of Finwë[]

| hideHouse of Finwë family tree[T 11][T 12] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Sons of Fëanor were Maedhros, Maglor, Celegorm, Curufin, Caranthir, Amras, and Amrod. Curufin was the father of Celebrimbor.

Analysis[]

Tuatha Dé Danaan[]

Scholars including Dimitra Fimi, A. Kinniburgh, and John Garth have connected the Noldor with the Irish Tuatha Dé Danaan as a possible influence. The parallels are both thematic and direct. In Irish mythology, the Tuatha Dé Danaan invade Ireland as a tall pale fair-haired race of immortal warriors and sorcerers. They have godlike attributes but human social organisation. They enter Ireland with what Kinniburgh calls a "historical trajectory", entering in triumph, living with a high status, and leaving diminished, just as the Noldor do in Middle-earth. They are semi-divine as Sons of Danu, just as the Noldor are counted among the first of the Children of Ilúvatar. Their immortality keeps them from disease and the frailty of age, but not from death in battle, an exact parallel with the Noldor. Nuada Airgetlám, the Tuatha Dé Danaan's first high king, is killed by Balor of the Evil Eye; Fëanor is killed by Gothmog the Lord of Balrogs.[5][6][7] Celebrimbor's[b] name means "Silver Hand" in Sindarin, the same meaning as Nuada's epithet Airgetlám in Irish Gaelic. Celebrimbor's making of powerful but dangerous rings, too, has been linked with the finding of a curse on a ring at the temple of Nodens, a Roman god whom Tolkien in his work as a philologist identified with Nuada.[8][9][10]

Germanic influence[]

Leslie A. Donovan notes that Tolkien's concept of exile, as principally exemplified by the Noldor, derives in part from Anglo-Saxon culture, in which he was an expert.[11]

The medievalist Elizabeth Solopova makes a connection between Middle English and Tolkien's description of Finwë's first wife Míriel as the most skilful of the Noldor at weaving and needlework; Solopova notes that Tolkien had proposed an etymology for the Middle English term burde, meaning lady or damsel, linking it to Old English borde, embroidery, and that he had given examples from both Old English and Old Norse where women were called weavers or embroiderers.[12]

Sub-creation[]

The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey writes that Tolkien was himself fascinated with artefacts and their "sub-creation", and that in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion consistently chooses to write about the "restless desire to make things" which is not quite, he notes, the same as the Christian sin of avarice or possessiveness. This made sense in the case of the Noldor, as for consistency their besetting sin ought not to be the same as Adam and Eve's, which was pride. In Valinor, Shippey writes, the equivalent of the Fall "came when conscious creatures became 'more interested in their own creations than in God's'", with Fëanor's forging of the Silmarils.[13] He adds that the smith-Vala Aulë is not only the patron of all craftsmen but the Vala most like Melkor, the first Dark Lord. The kinds of craftsmanship he encouraged among the Noldor was not only of physical things, but "'those that make not, but seek only for the understanding of what is' — the philologists, one might say", writes Shippey, including Tolkien's profession along with the Noldor's skill with letters and poetry.[13]

Character by ancestry[]

Shippey comments that the family tree of the House of Finwë is "essential", as Tolkien allocates character by ancestry; thus, Fëanor is pure Noldor, and so excellent as a craftsman, but his half-brothers Fingolfin and Finarfin have Vanyar blood from their mother, Indis. They are accordingly less skilful as craftsmen, but superior "in restraint and generosity".[14]

Decline and fall[]

Bradford Lee Eden states that in The Silmarillion, Tolkien focused on the Noldor as their history was "filled with the doom and fate so typical of medieval literature that determines the entire history of Middle-earth from the First Age to the time of The Lord of the Rings."[15] He notes that in many "parallel stories and tales" the fates of Elves and Men are tightly interwoven, leading inexorably to the decline and fading of the Elves and the rise of Men as the dominant race in the modern Earth.[15] The Tolkien scholar Matthew Dickerson writes that the theft of the Silmarils by Morgoth leads Fëanor and his sons into swearing their dreadful oath and leading the Noldor out of Valinor back to Middle-earth, at once a free choice and an exile.[3]

In culture[]

Nightfall in Middle-Earth, a 1998 studio album by the German power metal band Blind Guardian, contained multiple references to various Noldorin characters and the events they experience within the narrative of The Silmarillion. For example, "Face the Truth" has Fingolfin tell how he crossed the icy Helcaraxë, while in "Noldor (Dead Winter Reigns)" he regrets having left Valinor; "Battle of Sudden Flame" recalls the battle of Dagor Bragollach, which marked the turning point of the Noldor's war against Morgoth in the Dark Lord's favour; "The Dark Elf" recounts the birth of Maeglin, the son of Fingolfin's daughter Aredhel and Eöl the titular Dark Elf; "Nom the Wise" is an elegy by Beren to his friend Finrod Felagund.[16]

Notes[]

- ^ The published Silmarillion states that Gil-galad is the son of Fingon, but Christopher Tolkien would later categorically state in The Peoples of Middle-earth that this was an error and he is the son of Orodreth, who in turn was the son of Angrod, not of Finarfin.[citation needed]

- ^ Celebrimbor is a Noldor in some of Tolkien's versions, a Sindar in others.

References[]

Primary[]

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The History of Middle-earth, Vol. XI, The War of the Jewels: Part 4. "Quendi and Eldar" C: The Clan-names "Noldor"

- ^ The Silmarillion, ch. 15 "Of the Noldor in Beleriand"

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d The Silmarillion, ch. 5 "Of Eldamar and the Princes of the Eldalië"

- ^ Jump up to: a b The History of Middle-earth, Vol. XI, The War of the Jewels: Part 4, "Quendi and Eldar"

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. "Changes Affecting Silmarillion Nomenclature". Parma Eldalamberon (17): 125.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. "part 2, Late Writings (1968 or later): The Shibboleth of Fëanor". The Peoples of Middle-Earth. p. 365, note 61.

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, pp. 194, 294

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Silmarillion, ch. 13 "Of the Return of the Noldor"

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Silmarillion, ch. 9 "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- ^ The Silmarillion, ch. 6 "Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor"

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age": Family Trees I and II: "The house of Finwë and the Noldorin descent of Elrond and Elros", and "The descendants of Olwë and Elwë", ISBN 0-395-25730-1

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), Appendix A: Annals of the Kings and Rulers, I The Númenórean Kings, ISBN 0-395-08256-0

Secondary[]

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (1995). J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74816-9.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 282–284. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dickerson, Matthew (2013) [2007]. "Elves: Kindreds and Migrations". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Perkins, Dennis; Colbert, Stephen (16 August 2019). "Even elf king Lee Pace can't stump Tolkien expert Stephen Colbert". AV Club. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ Fimi, Dimitra (August 2006). ""Mad" Elves and "elusive beauty": some Celtic strands of Tolkien's mythology". Folklore. 117 (2): 156–170. doi:10.1080/00155870600707847. S2CID 162292626.

- ^ Kinniburgh, Anne (2009). "The Noldor and the Tuatha Dé Danaan: J.R.R. Tolkien's Irish Influences". Mythlore. 28 (1). article 3.

- ^ Garth, John (2003). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. Houghton Mifflin. p. 222. ISBN 0-618-33129-8.

- ^ Anger, Don N. (2013) [2007]. "Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 563–564. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Armstrong, Helen (May 1997). "And Have an Eye to That Dwarf". Amon Hen: The Bulletin of the Tolkien Society (145): 13–14.

- ^ Bowers, John M. (2019). Tolkien's Lost Chaucer. Oxford University Press. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-0-19-884267-5.

- ^ Donovan, Leslie A. (2013) [2007]. "Exile". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Solopova, Elizabeth (2014). "Middle English". In Lee, Stuart D. (ed.). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. John Wiley & Sons. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-470-65982-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 282–286. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eden, Bradford Lee (2013) [2007]. "Elves". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Ferretti, Marco. "Blind Guardian – Nightfall In Middle-Earth". Souterraine (in Italian). Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- High Elves