1905 Alberta general election

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

25 seats in the Legislative Assembly of Alberta 13 seats were needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1905 Alberta general election was the first general election held in the Province of Alberta, Canada on November 9, 1905, to elect twenty five members of the Alberta legislature to the 1st Alberta Legislative Assembly, shortly after the province was created out of the Northwest Territories on September 1, 1905.

The Alberta Liberal Party of Alexander C. Rutherford won twenty three of the twenty five seats in the new legislature, defeating the Conservative Party, which was led by a young lawyer, Richard Bennett, who later served as Prime Minister of Canada.

Prior to the 1905 election the two political parties saw numerous changes and defections, In Alberta a host of former Liberal-Conservative MLA's jumped ship to the Liberals, when Sir Wilfrid Laurier appointed the Liberal provisional government prior to the election. The Conservatives had no strong leader to rally around at the time as Frederick Haultain had moved to Saskatchewan.

Background[]

Government in the North-West Territories[]

In 1867, with Confederation, the new Dominion of Canada sought to expand westward and fulfil the provision of the British North America Act providing the option to admit Rupert's land to the Dominion.[1] In that same year, Canada's Parliament expressed this desire to the United Kingdom and soon after entered into talks with the Hudson's Bay Company to arrange for the transfer of the territory.[2][3]

After the Deed of Surrender was enacted, the United Kingdom transferred ownership of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson's Bay Company to the government of Canada.[3] However, integration of the territories into Canadian Confederation was delayed by the Red River Rebellion around the Red River Colony. Eventually the territories were admitted into Canadian Confederation on July 15, 1870, as the North-West Territories; barring the area around the Red River Colony, which was admitted into Canadian Confederation as the province of Manitoba.[4][5]

The unelected Temporary North-West Council was formed under the Temporary Government Act, 1870, but the first appointments by the Government of Canada were delayed until November 28, 1872.[6] The unelected body existed until October 1876 when it was replaced by the 1st Council of the North-West Territories, which consisted of appointed members, but with provisions for election of members when a district of an area of 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) had 1,000 people an electoral district could be set up.[6] This created a patchwork of represented and unrepresented areas, and there was no official or independent boundaries commission, all electoral law at the beginning was under the purview of the Lieutenant Governor. The North-West Territories population grew considerably along the Manitoba border during the 1870s which drove calls for franchise by settlers in the region, and a desire by many settlers to be incorporated into Manitoba.[7] In 1880 three electoral districts were created in the North-West Territories, two of which bordered the province of Manitoba.[7] The federal government heeded to the calls of the settlers and expanded the borders of Manitoba westward on July 1, 1881, encompassing much of the densely populated areas of the Territories.[7]

The first by-election occurred on March 23, 1881, in the Lorne district with Lawrence Clarke being elected to the Council. The election was conducted by voice vote, a qualified elector would tell the returning officer at a polling station who he was going to vote for and the results would be tallied. Under the terms of the Act eligible electors were males who had reached the age of majority, which was 21 years of age at that time. The act specified that electors must be bona fide males who were not aliens or unenfranchised Indians. Electors must also have resided in the territory for at least 12 months to the day of the writ being dropped.[8] The ad hoc by-election system continued to operate until 1888 when the Temporary North-West Council was replaced with an elected, responsible government through a Legislative Assembly selected in the 1888 North-West Territories general election.[9] Robert Brett, the representative for the district was appointed the Chairman of the Executive Committee, the defacto Premier of the North-West Territories.

The 1898 North-West Territories general election brought party politics to the Territories as Frederick W. A. G. Haultain's Liberal-Conservative Party defeated Brett's Liberal Party to form government. The beginning of party politics in the Territories sparked controversy and was not done through any Grass roots movement or formed on traditional ideological lines, and was done by Haultain in such a way that there was very little visibility to the public until years later after the party system began to mature.

Drive to provincehood[]

The earliest calls for Alberta's provincial autonomy came from Robert Brett in 1896, when he proposed the formation of a new province from the District of Alberta and District of Athabasca.[10] However, Brett's proposal did not gain support, and was opposed by Premier Haultain who preferred the Territories form one large province.[10] In 1900, Haultain secured unanimous approval of a resolution asking the Government of Canada to make an inquiry into the terms for provincial status of the Territories, and a year later Haultain and Arthur Sifton met with federal cabinet and submitted a draft constitution for a new province in the North-West Territories.[10] Wilfrid Laurier's government was not prepared consider the proposals, concerned about the difficult questions surrounding religious education, delegation of authority, and general apathy towards provincehood of Western Liberal Members of Parliament such as Frank Oliver.[10]

The 1902 North-West Territories general election only served to press the issue of provincehood. The Territories were under growing financial stress from limited revenue generation authorities and rising immigration. Haultain's government was reelected in a chaotic and partisan election, although despite the divisions, the Assembly continued to agree that provincial autonomy was a pressing concern.[10] During this time, Robert Borden, leader of the federal Conservative Party began to support provincehood for the Territories.[10] Frustrated in negotiations with the federal Liberal government, Haultain became increasingly identified with the Conservative Party and campaigned for it in the 1904 federal election. Despite Haultain's influence, Laurier's Liberals were re-elected and captured 58 per cent of the vote in the North-West Territories.[11]

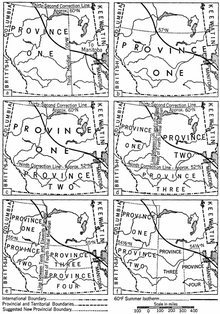

Laurier had promised during the election that his government would address the issue of provincial status, and despite efforts by Frank Oliver to downplay the benefits of autonomy through his Edmonton newspaper the Bulletin, the Liberal government's Speech from the Throne to start the 10th Canadian Parliament committed the government to action on the question of autonomy.[12] When the Autonomy Act split the North-West Territories along the 4th meridian of the Dominion Land Survey creating two provinces of roughly equal area of 275,000 square miles (710,000 km2) and 250,000 people.[13] The federal government under Laurier was of the opinion that one single province would be too large to effectively manage, and the territory above the 60th parallel north was unfit for agriculture, and therefore had little hope of "thick and permanent settlement".[14]

Terms of provincehood[]

The federal government drafted a bill for consultation, the bill provided for the establishment of two new provinces, retained federal ownership of public lands and resources, and provided financial terms which historian Lewis Thomas described as "not ungenerous".[15]

However, the greatest opposition came with clauses providing education rights to minority faiths through separate schools with the right enshrined to establish schools and be provided public funds.[15] The Laurier government had previously been embroiled in similar controversial schools question in Manitoba a decade earlier, which resulted in the Laurier-Greenway compromise and the removal of minority school rights in Manitoba, much to the opposition of French-Canadians and the Catholic Church.[16] The Haultain government had been engaged in a progressive reduction of the minority faith education privileges, with only eleven separate schools in operation by 1905.[15] Minister of the Interior and the Western Liberal representative in Cabinet Clifford Sifton, who had been travelling away from Ottawa during the drafting of the bill returned to Ottawa to resign his portfolio in protest,[15][17] while Finance Minister William Stevens Fielding considered resigning as well.[18] The education matter was highly controversial in English Canada, eliciting responses from Liberal newspapers and stoking fears for Liberal unity, however in the Territories the issue was not seen as significant.[18] Instead the main issue in the Territories was the location of the new provincial capital and ownership of public lands and resources.[18] The bill was amended to provide minority faiths the right to separate schools under provincial control.[18] As for continued federal control of natural resource rights, the provinces were each promised $375,000 annually with a provision for population growth.[19]

The selection of the new provincial capital became a driving issue, with the finalized Alberta Act identifying a "provisional" capital in Edmonton, with the final capital to be chosen by the new provincial government, against he competing interests of Calgary.[20] Calgary had the advantage of having a slightly larger population and located in a more densely populated part of the province, while Edmonton was the geographic centre of the province.[20] Edmonton had a strong advantage with the presence of Frank Oliver in cabinet, and a promise from Member of Parliament for Strathcona Peter Talbot that he would "fight to the finish" to ensure the provisional capital was in either Edmonton or Strathcona.[21]

The electoral districts for the first provincial election were established in the Alberta Act. The final layout favored northern Alberta with one additional district, despite Oliver and Talbot being aware that more than 1,000 more voters south of the Red Deer River participated in the 1904 Territorial election.[21] Calgary Liberal Charles Stuart argued that a non-partisan commission would be best to establish the boundaries, but was willing to back down when it became apparent the federal Liberals would not implement such a commission.[21] Despite opposition from Calgary Conservatives and Liberals, Oliver and Talbot continued to support the electoral boundaries favouring Northern Alberta, and Laurier kept the boundaries in place.[22]

Appointing a Lieutenant Governor and Premier[]

An interim government was appointed to handle the affairs of the new provinces from the date of confederation on September 1, 1905, and the election in November 1905. Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories Amédée E. Forget was appointed to the Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan while staunch Liberal George H. V. Bulyea a former member of the Territorial Legislature was appointed to the Lieutenant Governor role in Alberta.[23][24] Frank Oliver was considered for the role of Alberta's first Premier, but instead sought the role of Minister of the Interior in Laurier's government instead.[25] Talbot was also strongly considered by Laurier and other members of the Liberal Party for Alberta's first Premier.[25] Talbot however, was not a wealthy individual and stated that politics was beyond his financial means and strength, and instead sought a position in the Senate, which he was appointed to in 1906.[23] Historian Lewis Thomas states that he believes that Laurier would have appointed Talbot the first Premier of Alberta if he had showed interest in the position.[26] The next candidate was Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the member of the North-West Territories Assembly for Strathcona, although Laurier remained quiet on the decision, leading to some speculation.[26]

Speculation on the future Premier ended when Rutherford was named the leader of the Alberta Liberal Party on August 13, 1905, and a few days later Haultain announced he would remain in Saskatchewan to form a provincial rights party.[26] Similarly, R. B. Bennett, a young Calgary lawyer was chosen as the leader of the Alberta Conservative Party shortly after on August 16, 1905.[26][27] Historian Lewis Thomas argues that Laurier's decision to remain silent on naming a Premier helped weaken Haultain's position as the heir apparent, and if Laurier had named Rutherford earlier, Haultain and his supporters of non-partisan government could have mounted a stronger protest and campaign.[28] Laurier's appointment of staunch Liberals in Bulyea, Forget, Rutherford and Walter Scott ushered in party politics to the new prairie provinces.[28]

On September 2, 1905, Lieutenant Governor Bulyea in his first official act called on Rutherford to form the provincial government, and was sworn in as Alberta's first Premier.[29]

Issues[]

Capital city[]

Section 9 of the Alberta Act prescribed that the seat of government would be held in Edmonton, but provided authority to the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta to move the capital. Essentially, naming Edmonton as a temporary capital until a decision could be made by the elected provincial government.[30]

The competition for the provincial capital was fierce between Calgary and Edmonton. At events in Edmonton, Liberal Attorney General Charles Wilson Cross assured the crowds that Edmonton would remain the capital, while his Conservative candidate William Antrobus Griesbach stated that all thirteen northern conservative candidates supported Edmonton as the capital.[31]

At the same time, Conservative leader Bennett told crowds in Calgary that if elected, his conservative government would establish the capital in Calgary.[31] Bennett's Liberal opponent and Minister of Public Works William Henry Cushing pledged to bring the capital to Calgary, earning him the endorsement of the Calgary Albertan published by William McCartney Davidson.[31] Meanwhile, the Calgary Herald opposed Cushing, and argued that the federal liberals were "directed toward the destruction of that commercial and industrial supremacy" of Calgary, and accused the provincial liberals of being puppets of the federal party.[32][33]

Residents of Red Deer made an effort to position the community as a compromise capital, located approximately halfway between the two competing cities.[34] Although the small community and disinterest from federal elected officials hampered Red Deer's efforts for being considered a viable capital.[35]

After the election resulted in an overwhelming Liberal majority, Premier Rutherford announced the location of the capital city was to be chosen by an open vote of the Legislature.[36] The Calgary Board of Trade and newspapers recognizing the uphill battle to be named capital gave very little effort in rallying Calgarians and southern Albertans to the cause.[37] Furthermore, Red Deer's elected member John Thomas Moore, who was chosen as the man "most likely to secure the capital", was largely ineffective as he left for the east after the election to attend to personal business.[38] On April 25, 1906, Cushing made a motion in the Legislature to move the capital to Calgary, a second motion was made by Moore to move the capital to Red Deer.[30] A vote was held, with eight members voting for Calgary and a majority 16 voting for Edmonton.[39]

Education[]

After bitter debate across Canada, the proposed Alberta Act was amended by Laurier in second reading on March 22,[40] and later passed by the 10th Canadian Parliament with provisions providing minority faiths the right to separate schools under provincial control.[18] Alberta conservatives rallied against the education provisions, but the party and leadership declined to make the repeal of the provisions an issue in the campaign.[41] The Alberta liberals chose to campaign on accepting the decisions of parliament in regards to the schools issue, and instead focus on "an efficient system of public schools".[42]

Campaign[]

The writ for the election was issued on October 19, 1905, with the election scheduled to take place three weeks later on November 9.[43] Liberal William Bredin was the only candidate acclaimed, with no contest necessary in the Athabasca.[44]

Liberal[]

Rutherford began his term as the appointed Premier by forming a cabinet inclusive of all the major regions of the province. Charles Wilson Cross of Medicine Hat was appointed Attorney General, William Henry Cushing of Calgary as Minister of Public Works, William Finlay of Edmonton as Minister of Agriculture, and Leverett George DeVeber of Lethbridge as Minister without a portfolio was added to cabinet.[45][29]

The Liberal platform was adopted at the party convention in Calgary in October 1905.[41] Recognizing the party was chosen to form government prior to the election, and the friendly relations with the Liberal federal government, the Liberal platform skirted mild and controversial issues.[42] The issues of separate schools and public lands were not addressed, and instead the convention noted adherence to "the principle of Provincial rights" as the party policy.[42] The Liberals instead sought an efficient system of public schools supported by taxation and regulated by the provincial government.[42][46] The Liberals responded to conservative calls for public ownership of utilities by recognizing that public ownership was desirable and should be considered.[42][46] The platform also advocated for agricultural industry, and was against incurring provincial debt.[42][46]

The Liberal Party received support from the Calgary Albertan newspaper,[47] as well as Oliver's Edmonton Bulletin.

Conservative[]

With the exodus of Haultain to Saskatchewan, the Conservative movement was in desperate need of a new charismatic leader to face the incumbent Liberal party, which they found in the young Calgary lawyer R. B. Bennett. The province was politically divided on geographic grounds, with Edmonton and northern Alberta leaning towards the Liberal Party, and Calgary and southern Alberta leaning more conservative.[48] Calgary and southern Alberta's conservative leaning was linked to the presence of the Canadian Pacific Railway which was generally regarded as exercising influence on behalf of the conservative movement.[48]

The Conservative Party policy focused on protesting the federal government retaining public lands and resources, develop government owned utilities such as telephone lines, and advocated for government construction and maintenance of roads and bridges.[49] While Griesbach sought and Edmonton conservatives sought to demand Edmonton as the provincial capital, the party took no official position on the matter.[49] The party did not take an official stance on the issue of separate schools for minority faiths being included in the Alberta Act, owing to the influence of Bennett and Senator James Lougheed.[41] Although Bennett did make a speech decrying the federal government including the separate school provisions as an attack on provincial rights.[41] Historian Lewis Thomas describes the Conservative platform as being "defensive", lacking initiative of the liberal platform and seeming almost non-partisan in nature.[41]

The personality and character of Conservative leader Bennett became one of the central issues of the campaign. Liberal newspaper Edmonton Bulletin pointed out Bennett's employment as a solicitor for the Canadian Pacific Railway, Bell Telephone Company and Calgary Water Power Company were used to illuminate a "corporation connection" with Bennett and the Conservative party.[50] Similar concerns were raised by the conservative leaning Calgary Herald prior to Bennett's confirmation as leader.[47] Historian Lewis Thomas describes the Liberal strategy to connect Bennett to the Canadian Pacific Railway as successful, noting many in Alberta resented the corporation for a myriad of reasons.[51] Bennett did receive a surprising endorsement from Bob Edwards the publisher of the Calgary Eye-Opener,[47] who had previously published stories critical of Bennett and his employer, the Canadian Pacific Railway.[52] Although Edwards contended that Bennett was a poor leader who sought "non-entities and spineless nincompoops as followers".[47]

The Edmonton Bulletin also ran a number of stories alleging corruption in the Conservative Party. The Bulletin accused the Calgary Conservative organizer William L. Walsh of attempting to bribe Daniel Maloney to run as a candidate in the St. Albert constituency.[51][53]

Election[]

Electoral boundaries[]

The boundaries of the electoral districts for the first Alberta general election were prescribed in the Alberta Act (Canada) and were a source of controversy with accusations of gerrymandering in favour of the Liberal Party and northern Alberta.[a] Calgary based newspapers the Calgary Herald, Calgary Albertan, and Eye-Opener made claims that the borders constituted preferential treatment for Edmonton and northern Alberta.[55] Prime Minister Laurier had received assurances that the distribution was fair from Alberta Members of Parliament Talbot and Oliver, but when word of Calgary's opposition reached Ottawa, Laurier summoned Talbot to explain the situation.[55] On May 19, 1905, Talbot spent the morning convincing Laurier that the distribution was fair, Laurier agreed, but remained cautious and asked that the boundaries be submitted to a commission of judges for review.[55] Laurier called a second meeting with Talbot on May 28 after receiving correspondence from Calgary Liberals, but was once again put at ease with Talbot's explanation, and the concept of the judicial commission for review was likewise put to rest.[56]

Conservative Member of Parliament for Calgary Maitland Stewart McCarthy made no effort to advance Calgary and southern Alberta's claims for fair representation until June 20, 1905, much too late to make a difference.[56] In the two hour speech, McCarthy called for 15 seats in southern Alberta and 10 in northern Alberta, and demanded a judicial commission to oversee the boundaries.[57] However, McCarthy made no effort to participate in the early drafting process of the Alberta Act, instead hoping for an invitation to participate, one which never came from Oliver, the brunt of his efforts came too late in the drafting process.[57]

The question of whether there was population based gerrymandering returns different responses. Historian Lewis Thomas notes the final layout favoured northern Alberta with one additional district, despite Oliver and Talbot being aware that more than 1,000 more voters south of the Red Deer River participated in the 1904 Territorial election.[21] Alexander Bruce Kilpatrick notes that the census results from 1906 shows that if the 38th township is chosen as the dividing line (City of Red Deer), there were 93,601 persons in northern Alberta and 87,381 in southern Alberta, with an additional 4,430 residing in the 38th township.[58] Kilpatrick claims that people misconstrued where the population of the Strathcona census district lived, assuming most were south of the 38th Township, when a significant majority were in fact north of the township.[54]

Kilpatrick however, describes the layout of the electoral districts as "blatant manipulation of the electoral map to suit a particular purpose".[59] In particular Kilpatrick claims that Oliver designed the constituencies to maximize the influence of Edmonton, the borders did not align with the previous constituencies from the North-west Territories legislature, and instead was drawn to have several ridings touching the city's borders.[59] At the same time, Calgary did not have the same advantages in design, and was reduced from two seats in the North-west Territories Legislature to one in the new Alberta Legislature.[59]

Voting and eligibility[]

Voter and candidate eligibility requirements remained in place under the rules set by the North-West Legislative Assembly under The Territories Elections Ordinance.[60][61] The right to vote was provided to male British subjects who were 21 years of age or older, and had resided in the North-West Territories for at least 12 months, and the electoral district for the three months prior to the vote.[61] The vote took place on November 9, 1905 with polls open between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m..[61]

In 1905 Albertans would vote by marking an "X" on a blank sheet of paper using a coloured pencil which corresponded to candidate whom they wished to vote for, red for Liberal and blue for Conservative.[21][62] Scrutineers were able to contest the eligibility of a person voting, the voter would then be required to fill out a form with their information which would be deposited in an envelope along with their ballot. The voter would then be required to return within two days to contest the objection to a Justice of the Peace.[63]

Irregularities[]

Calgary[]

The election in 1905 was a bitter one, especially in Calgary and Southern Alberta where the Liberals were accused of vote tampering and interfering with Conservative voters. Recounts especially in Calgary took almost a month and saw the result swing back and forth. The scandal led to the arrest of some key Liberal organizers, including William Henry Cushing's campaign manager, who had been a returning officer at a Calgary polling station. A liberal organizer was convicted of bribery for paying a voter $10 not to defend his ballot which was challenged during the count.[64][65] The Calgary contest was eventually called for Cushing with a margin of 37 votes.[66]

Peace River[]

The Peace River electoral district was contested between Liberal James Cornwall and Independent Lucien Dubuc. Dubec received the greater number of votes, but the election results were overturned by the Executive Council in mid-January due to significant irregularities, leaving the seat vacant.[67] A new election was held on February 15, 1906. An appeal was launched into the legality of Cabinet deciding on the legitimacy of an election, which was upheld when Judge David Lynch Scott found the court had no jurisdiction unless delegated by the legislature.[68]

Thomas Brick declared his candidacy in the new election for the Liberals after being asked to run by a large group of people who appeared at his homestead. He faced James Cornwall who attempted to re-win his seat and he also ran under the Liberal banner. The runner up candidate from the original 1905 election Conservative candidate Lucien Dubuc did not run again leaving a rare two-way race under the same party banner. Thomas Brick would go on to defeat James Cornwall in a landslide.[69]

| District | Member | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Election night | |||

| Peace River | James Cornwall | Liberal | |

| February 15, 1906 | |||

| Peace River | Thomas Brick | Liberal | |

Aftermath[]

The Liberal Party under Premier Rutherford dominated the election, capturing 22 of the 25 available seats in a landslide victory, while Bennett's Conservative Party captured a mere two seats and Bennett himself was not successful in Calgary.[70] The Liberals were confident that they would form a majority government prior to the election, but had not expected so many seats. Liberal MP Talbot estimated the Liberals would capture 18 seats.[70] The Conservatives did not expect the defeat, being successful in nominating candidates in 22 of the 25 ridings and have entrenched support in southern Alberta.[70] The conservatives attributed their defeat to the Roman Catholic vote which was felt to be sympathetic to Laurier for his support of separate schools,[70] with Bennett himself attributing his loss in Calgary to Roman Catholic influences,[71] labour vote and his time traveling outside of the district.[72] Bennett quickly resigned his position as leader and temporarily retired from politics.[73] Conservatives also attributed the loss to non-Anglo-Saxon voters.[70] However, the Conservative victories by Cornelius Hiebert in Rosebud, and Albert Robertson in High River went against this trend. Hiebert, a Russian-born Mennonite, won in his constituency, while Robertson was aided by a third candidate syphoning votes from the incumbent Liberal opponent.[71]

Historian Lewis Thomas argues the Liberal landslide was due to the incumbent position of the Liberal government which in its two months had not been tested with scandal or policy, making it difficult for effective opposition and criticism, all the while being able to maintain all the powers of patronage an incumbent would have.[71] The Liberals effectively exercised the machinery of government from both the provincial and federal level, with Thomas noting a few surviving written suggestions for Liberal appointments.[74] Furthermore, Thomas argues the strong positions taken by the Conservative Party on provincial right to control the school system and public lands did not make a significant impression on voters.[71]

Results[]

| Party | Votes | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 14,078 | 55.9% |

22 / 25 (88%)

| |

| Conservative | 9,342 | 37.1% |

2 / 25 (8%)

| |

| Others and independents | 1,743 | 6.9% |

1 / 25 (4%)

| |

Full results[]

| Party | Party leader | Candidates | Seats | Popular vote | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1905 | % seats | Votes | % | ||||

| Liberal | Alexander Cameron Rutherford | 26[b] | 22 | 88% | 14,078 | 55.95% | |

| Conservative | R. B. Bennett | 22[c] | 2 | 8% | 9,342 | 37.13% | |

| Independent and no affiliation | 7 | 1 | 4% | 1,743 | 6.92% | ||

| Total | 56 | 25 | 100% | 25,163 | 100% | ||

| Source: A Report on Alberta Elections 1905-1982 (Edmonton: Provincial Archives of Alberta, 1983) Alberta Advocate November 17, 1905[75] | |||||||

Members of the Legislative Assembly elected[]

For complete electoral history, see individual districts

| Electoral District | Liberal | Conservative | Other | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athabasca | William Bredin Acclaimed |

|||||

| Banff | Charles W. Fisher 421 53.70% |

Robert Brett 363 46.30% |

||||

| Calgary | William Cushing 1,030 42.39% |

R. B. Bennett 993 40.86% |

Alex D. Macdonald (Ind.) 407 16.75% | |||

| Cardston | John William Woolf 480 69.57% |

John F. Parish 210 30.43% |

||||

| Edmonton | Charles Wilson Cross 1,209 70.09% |

William Antrobus Griesbach 516 29.91% |

||||

| Gleichen | Charles Stuart 667 51.03% |

John W. Hayes 640 48.97% |

||||

| High River | Richard Alfred Wallace 555 42.21% |

Albert Robertson 578 43.95% |

Wilford B. Thorne (Ind.) 182 13.84% | |||

| Innisfail | John A. Simpson 408 50.06% |

Sam J. Curry 407 49.94% |

||||

| Lacombe | William Puffer 612 52.8% |

Andrew Gilmour 547 47.2% |

||||

| Leduc | Robert Telford 481 63.46% |

C.E.A. Simons 277 36.54% |

||||

| Lethbridge | Leverett DeVeber 639 56.55% |

William Carlos Ives 491 43.45% |

||||

| Macleod | Malcolm McKenzie 584 58.11% |

David J. Crier 368 36.62% |

Duncan J.D.K. Campbell (Ind.) 53 5.27% | |||

| Medicine Hat | William Finlay 575 51.71% |

Francis O. Sissions 537 48.29% |

||||

| Pincher Creek | John Plummer Marcellus 550 39.40% |

Frank A. Sherman 436 31.23% |

John H.W.S. Kemmis (Ind.) 410 29.37% | |||

| Ponoka | John R. McLeod 375 58.59% |

John A. Jackson 265 41.41% |

||||

| Red Deer | John T. Moore 524 48.03% |

Leonard Gaetz 479 43.9% |

Alexander D. McKenzie (Ind.) 88 8.07% | |||

| Rosebud | Michael Clark 545 43.25% |

Cornelius Hiebert 589 46.75% |

Joseph Reid (Ind.) 126 10.00% | |||

| St. Albert | Lucien Boudreau 391 49.00% |

Henry William McKenney (Ind. Liberal) 407 51.00% | ||||

| Stony Plain | John McPherson 354 57.94% |

Dan Brox 187 30.61% |

Conrad Weidenhammer (Ind.) 70 11.46% | |||

| Strathcona | Alexander Cameron Rutherford 625 67.13% |

Frank W. Crang 306 32.87% |

||||

| Sturgeon | John R. Boyle 721 76.78% |

Frank Knight 218 23.22% |

||||

| Vermilion | Matthew McCauley 673 73.07% |

Frank Fane 248 26.93% |

||||

| Victoria | Francis A. Walker 949 69.88% |

John W. Shera 409 30.12% |

||||

| Wetaskiwin | Anthony Rosenroll 552 66.51% |

Robert MacLachlan Angus 278 33.49% |

||||

See also[]

- List of Alberta political parties

Notes[]

- ^ During the debates in Parliament, it was generally agreed upon that the dividing line of northern and southern Alberta was township 38 of the Alberta Township System. Township 38 includes the City of Red Deer, Alberta.[54]

- ^ Two Liberal candidates contested the Peace River district after the result of the first election was voided.

- ^ The Conservatives did not nominate candidates in three ridings. They did nominate a candidate originally for Peace River, but the result was set aside and no Conservative stood for the second election in Peace River.

References[]

- ^ Lingard 1946, p. 27.

- ^ "Correspondence relating to Surrender of Rupert's Land by Hudson's Bay Company and Admission into Dominion of Canada". House of Commons Papers. 43.

- ^ a b Lingard 1946, p. 28.

- ^ Lingard 1946, p. 29.

- ^ Martin, Chester Bailey (January 15, 1973). Dominion Lands Policy. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. pp. 1–. GGKEY:ND80W0QRBQN. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Lingard 1946, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Nicholson 1979, p. 115.

- ^ Ordinances of the Northwest Territories 1881. P. G. Laurie, Printer to the Government of the Northwest Territories. 1882. p. 53.

- ^ Lingard 1946, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas 1959, p. 5.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 6.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 7.

- ^ Nicholson 1979, p. 136.

- ^ Nicholson 1979, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d Thomas 1959, p. 8.

- ^ Gray 1991, p. 82.

- ^ Lingard 1946, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas 1959, p. 9.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 10.

- ^ a b Thomas 1959, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas 1959, p. 13.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 14.

- ^ a b Thomas 1959, p. 17.

- ^ Babcock 1989, p. 25.

- ^ a b Thomas 1959, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Thomas 1959, p. 18.

- ^ "Conservative Convention At Red Deer Opened Auspiciously Last Night". The Daily Herald. August 17, 1905. p. 1. ProQuest 2252260021.

- ^ a b Thomas 1959, p. 19.

- ^ a b Babcock 1989, p. 27.

- ^ a b Kilpatrick 1980, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Kilpatrick 1980, p. 100.

- ^ Kilpatrick 1980, p. 101.

- ^ "Our Educational System". The Daily Herald (6, 384). November 4, 1905. p. 2. ProQuest 2252272797.

- ^ Kilpatrick 1980, p. 66.

- ^ Kilpatrick 1980, p. 73.

- ^ Kilpatrick 1980, p. 104.

- ^ Kilpatrick 1980, p. 105.

- ^ Kilpatrick 1980, p. 106.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 38.

- ^ Lingard 1946, p. 184.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas 1959, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas 1959, p. 25.

- ^ Hopkins 1906, p. 237.

- ^ Hopkins 1906, p. 238.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Babcock 1989, p. 145–147.

- ^ a b c d Gray 1991, p. 91.

- ^ a b Thomas 1959, p. 21.

- ^ a b Thomas 1959, p. 23.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 26.

- ^ a b Thomas 1959, p. 27.

- ^ Gray 1991, p. 86.

- ^ "Where did the Money Come From?". Daily Edmonton Bulletin (256). November 6, 1905. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Kilpatrick 1980, p. 94.

- ^ a b c Kilpatrick 1980, p. 88.

- ^ a b Kilpatrick 1980, p. 89.

- ^ a b Kilpatrick 1980, p. 90.

- ^ Kilpatrick 1980, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Kilpatrick 1980, p. 96.

- ^ The Territories Elections Ordinance, C.O. 1905, c. 3

- ^ a b c Office of the Chief Electoral Officer & Legislative Assembly Office 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Office of the Chief Electoral Officer & Legislative Assembly Office 2006, p. 35.

- ^ The Territories Elections Ordinance, C.O. 1905, c. 3, s. 40–49, 59–71

- ^ "Liberal Committeeman Jailed on a Charge of Bribery". The Daily Herald (6391). November 15, 1905. p. 1. ProQuest 2252284596.

- ^ "Liberal Committeeman Lake Found Guilty of Bribery". The Daily Herald (6470). February 12, 1906. p. 1. ProQuest 2252286664.

- ^ "Cushing Wins by 37". The Daily Herald (6397). November 23, 1905. p. 1. ProQuest 2252252097.

- ^ "The Election Not Recognized". The Edmonton Bulletin. January 16, 1906. p. 1. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ "Court Had No Jurisdiction". The Edmonton Bulletin. March 7, 1906. p. 1. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ Mahé, Yvette T. M., ed. (1974). I remember Peace River, Alberta and adjacent districts. Part I. The Women's Institute of Peace River. pp. 30–31. OCLC 911779276.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas 1959, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Thomas 1959, p. 29.

- ^ Gray 1991, p. 92.

- ^ Gray 1991, p. 93.

- ^ Thomas 1959, p. 30.

- ^ "Members elected to first legislature November 17, 1905". Alberta Advocate. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- Works cited

- Office of the Chief Electoral Officer; Legislative Assembly Office (2006). A Century of Democracy: Elections of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta, 1905-2005. The Centennial Series. Edmonton, AB: Legislative Assembly of Alberta. ISBN 0-9689217-8-7. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Babcock, Douglas R. (1989). A Gentleman of Strathcona: Alexander Cameron Rutherford. Calgary: The University of Calgary Press. ISBN 0-919813-65-8.

- Gray, James H. (1991). R.B. Bennett: The Calgary Years. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-5975-8.

- Hall, David (Winter 2005). "The Transition to Partisanship: Alberta Political Party Platforms, 1905". Canadian Issues: 21–23. ISSN 0318-8442. ProQuest 208684009.

- Hopkins, J. Castell (1906). The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs, 1905. Toronto: The Annual Review Publishing Company.

- Kilpatrick, Alexander Bruce (1980). "A Lesson in Boosterism: The Contest for the Alberta Provincial Capital, 1904-1906". Urban History Review. 8 (3): 47–109. doi:10.7202/1019362ar. ISSN 0703-0428.

- Lingard, C. Cecil (1946). Territorial Government in Canada: The Autonomy Question in the old North-west Territories. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7095-1.

- Nicholson, Norman L. (1979). The boundaries of the Canadian confederation. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. ISBN 978-0-7705-1742-7.

- Thomas, Lewis Gwynne (1959). The Liberal Party in Alberta. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-5083-0.

- 1905 elections in Canada

- Elections in Alberta

- November 1905 events

- 1905 in Alberta