1998–1999 Malaysia Nipah virus outbreak

| 1998–1999 Malaysia Nipah virus outbreak | |

|---|---|

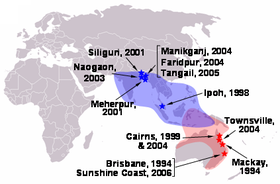

The first site of the virus in Ipoh in 1998 and later occurrence to other places with the virus extent in blue while Hendra virus in red, both belong to the Paramyxoviridae family. | |

The 1998–1999 Nipah virus outbreak areas in West Malaysia, blue is the origin source of the virus while the red are further affected areas. | |

| Disease | Nipah virus infection |

| Virus strain | Nipah virus |

| First outbreak | Ipoh, Perak |

| Index case | September 1998 |

| Confirmed cases | 265 |

Deaths | 105 |

The 1998–1999 Malaysia Nipah virus outbreak was a Nipah virus outbreak occurring from September 1998 to May 1999 in the states of Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Selangor in Malaysia. A total of 265 cases of acute encephalitis with 105 deaths caused by the virus were reported in the three states throughout the outbreak.[1] The Malaysian health authorities at the first thought Japanese encephalitis (JE) was the cause of infection which hampered the deployment of effective measures to prevent the spread before being finally identified by a local virologist from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya that it was a newly discovered agent named Nipah virus (NiV). The disease was as deadly as the Ebola virus disease (EVD), but attacked the brain system instead of the blood vessels.[1][2] University of Malaya's Faculty of Medicine and the University of Malaya Medical Centre played a major role in serving as a major referral centre for the outbreak, treating majority of the Nipah patients and was instrumental in isolating the novel virus and researched on its features.

This emerging diseases where it caused major losses to both animal and human lives, affecting livestock trade and created a significant setback to the swine sector of the animal industry in Malaysia.[3] The country also became the origin of the virus where it had no more cases since 1999 but further outbreaks continue to occur in Bangladesh and India.[4][5]

Background[]

The virus firstly struck pig-farms in the suburb of Ipoh in Perak with the occurrence of respiratory illness and encephalitis among the pigs where it is firstly thought to be caused by Japanese encephalitis (JE) due to 4 serum samples from 28 infected humans in the area tested positive for JE-specific Immunoglobulin M (IgM) which is also confirmed by the findings of World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Tropical Disease at the Nagasaki University.[1] A total of 15 infected people died during the ensuing outbreak before the virus began to spread into Sikamat, Nipah River Village and Pelandok Hill in Negeri Sembilan when farmers affected by the control measures began to sell their infected pigs to these areas.[1] This resulted 180 patients infected by the virus and 89 deaths. With further movement of the infected pigs, more cases emerged from around Sepang District and Sungai Buloh in Selangor with 11 cases and 1 death reported among abattoir workers in Singapore who had handled the infected pigs imported from Malaysia.[1]

Authorities response and further investigation[]

Since the cause was firstly wrongly identified, early control measures such as mosquito foggings and vaccination of pigs against JE were deployed to the affected area which proved to be ineffective since more cases emerged despite the early measures.[1] With the increasing deaths reported from the outbreak, this caused nationwide fear from the public and the near collapse of local pig-farming industry.[1] Most healthcare workers who were taking care of their infected patients had been convinced that the outbreak was not caused by JE since the disease affected more adults than children, including those who had been vaccinated earlier against JE.[1] Through further autopsies on the deceased, the findings were inconsistent from the earlier results where they suggest it may come from another agent.[1] This was supported with several reasons such as all of the infected victims had direct physical contacts with pigs and all of the infected pigs had developed severe symptoms of barking cough before dying.[1] Despite the evidence gathered from autopsies results with new findings among local researchers, the federal government especially the health authorities insisted that it was solely caused by JE which delayed further appropriate action taken for the outbreak control.[1]

Identification of the source of infection[]

In early March 1999, a local medical virologist at the University of Malaya named Dr Chua Kaw Beng finally found the root cause of the infection.[2] Through his findings, the infection was indeed caused by a new agent named Nipah virus (NiV), taken from the investigation area name of Nipah River Village (Malay: Kampung Sungai Nipah),[6] where it is still unknown to available science records at the time.[1][7] The virus origin is identified from a native fruit bat species.[8] Together with the Hendra virus (HeV), the novel virus is subsequently recognised as a new genus, Henipavirus (Hendra + Nipah) in the Paramyxoviridae family.[1] He found that NiV and HeV shared enough epitopes for HeV antigens to be used in a prototype serological test for NiV antibodies which helped in the subsequent screening and diagnosis of NiV infection.[1] Following the findings, widespread surveillance of pig populations together with the culling of over a million pigs was undertaken and the last human fatality occurred on 27 May 1999.[1] The outbreak in neighbouring Singapore also ended with immediate prohibition of pigs importation to the country and their subsequent closure of abattoirs.[1] The virus discovery received the attention from the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and Singapore General Hospital (SGH) who giving swift assistance towards the characterisation of the virus and the development of surveillance and control measures.[1]

Aftermath[]

Until 2010s, the pig farming ban on Pelandok Hill was still in force to prevent the recurrence of the outbreak despite some people had quietly restarted the business after being instigated by community leaders.[9] Most of the surviving pig farmers have turned to palm oil and Artocarpus integer (cempedak) cultivation.[10] Since the virus has been named Nipah from the sample taken in Nipah River Village of Pelandok Hill, the latter area has become synonyms with the deadly virus.[11]

Memorials[]

In 2018, the outbreak are being memorialised in a newly constructed museum named Nipah River Time Tunnel Museum in the Nipah River Village with several of the surviving victims stories have been filmed in a documentary which will be featured at the museum.[10]

See also[]

Further reading[]

- Yob, J. M.; Field, H.; Rashdi, A. M.; Morrissy, C.; van der Heide, B.; Rota, P.; bin Adzhar, A.; White, J.; Daniels, P.; Jamaluddin, A.; Ksiazek, T. (2001). "Nipah virus infection in bats (order Chiroptera) in peninsular Malaysia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 7 (3): 439–441. doi:10.3201/eid0703.010312. PMC 2631791. PMID 11384522.

- Lam, Sai Kit; Chua, Kaw Bing (2002). "Nipah Virus Encephalitis Outbreak in Malaysia". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 34 (2): S48–S51. doi:10.1086/338818. PMID 11938496 – via Oxford Academic.

- Lam, S. K. (2003). "Nipah virus--a potential agent of bioterrorism?". Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya. 57 (1–2): 113–9. doi:10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00204-8. PMID 12615307 – via National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- Hughes, James M.; Wilson, Mary E.; Luby, Stephen P.; Gurley, Emily S.; Hossain, M. Jahangir (2009). "Transmission of Human Infection with Nipah Virus". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 49 (11): 1743–1748. doi:10.1086/647951. PMC 2784122. PMID 19886791 – via Oxford Academic.

- Banerjee, Sayantan; Gupta, Nitin; Kodan, Parul; Mittal, Ankit; Ray, Yogiraj; Nischal, Neeraj; Soneja, Manish; Biswas, Ashutosh; Wig, Naveet (2019). "Nipah virus disease: A rare and intractable disease". Intractable and Rare Diseases Research. 8 (1): 1–8. doi:10.5582/irdr.2018.01130. PMC 6409114. PMID 30881850 – via National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- Mazzola, Laura T.; Kelly-Cirino, Cassandra (2019). "Diagnostics for Nipah virus: a zoonotic pathogen endemic to Southeast Asia". The BMJ. 4 (2): e001118. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001118. PMC 6361328. PMID 30815286.

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Looi, Lai-Meng; Chua, Kaw-Bing (2007). "Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia" (PDF). The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. Department of Pathology, University of Malaya and National Public Health Laboratory of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. 29 (2): 63–67. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019.

- ^ a b Doucleff, Michaeleen; Greenhalgh, Jane (25 February 2017). "A Taste For Pork Helped A Deadly Virus Jump To Humans". NPR. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

The disease was as deadly as Ebola, but instead of attacking blood vessels, it attacked the brain. Young men would be healthy one day, the next day their brains would swell up. They couldn't walk or talk. They'd become comatose and some of them became paralysed. Yet the Malaysian government told people not to worry, it said the disease was coming from mosquitoes and it had it under control because it was spraying for mosquitoes. Both C. T. Tan and Kaw Bing Chua thought the government was wrong and there was one big clue: No Muslims were getting sick, mosquitoes don't care which religion you practice so if the disease was coming from mosquitoes, you would have Muslims, Hindus and Christians getting sick. But only Chinese Malaysians were catching the disease — and even more specifically, only Chinese farmers raising pigs. As you know, Muslims don't handle pigs.

- ^ "Manual on the Diagnosis of Nipah Virus Infection in Animals" (PDF). RAP Publication. Food and Agriculture Organization: v [11/90]. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019.

- ^ Ang, Brenda S. P.; Lim, Tchoyoson C. C.; Wang, Linfa (2018). "Nipah Virus Infection". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 56 (6): e01875-17. doi:10.1128/JCM.01875-17. PMC 5971524. PMID 29643201 – via American Society for Microbiology.

- ^ "Nipah virus". World Health Organization. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "Nipah Virus Infection" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2019.

The virus is named after the Malaysian village where it was first discovered. This virus along with Hendra virus comprises a new genus designated Henipavirus in the subfamily Paramyxovirinae.

- ^ "Nipah Virus (NiV)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Enserink, Martin (2000). "Malaysian Researchers Trace Nipah Virus Outbreak to Bats". Science. 289 (5479): 518–9. doi:10.1126/science.289.5479.518. PMID 10939954 – via American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- ^ Singh, Sarban (3 July 2014). "1998 ban on pig farming in Bukit Pelanduk still in force". The Star. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ a b Yong, Yimie (14 April 2018). "Nipah virus outbreak memorialised in museum". The Star. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ Yi, Chang (27 May 2018). "Bukit Pelandok revisited". The Borneo Post. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Paramyxoviridae

- Health disasters in Malaysia

- Disease outbreaks in Singapore