1999 Constituent National Assembly

Constituent National Assembly Asamblea Nacional Constituyente | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Succeeded by | 2017 Constituent Assembly |

| Leadership | |

President | |

| Structure | |

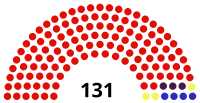

| Seats | 131 |

| |

Political groups | Government

Opposition

|

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Federal Legislative Palace, Caracas | |

| Website | |

| [1] | |

The Constituent National Assembly (Spanish: Asamblea Nacional Constituyente) or ANC was a constitutional convention held in Venezuela in 1999 to draft a new Constitution of Venezuela, but the assembly also gave itself the role of a supreme power above all the existing institutions in the republic. The Assembly was endorsed by a referendum in April 1999 which enabled Constituent Assembly elections in July 1999. Three seats were reserved for indigenous delegates in the 131-member constitutional assembly,[1] and two additional indigenous delegates won unreserved seats in the assembly elections.[2]

The constitution was later endorsed by the referendum in December 1999, and new general elections were held under the new constitution in July 2000. This ended the Punto Fijo Pact and ushered in the present-day Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

Precedents[]

President Chávez called for a public referendum - something virtually unknown in Venezuela at the time - which he hoped would support his plans to form a constitutional assembly, composed of representatives from across Venezuela, as well as from indigenous tribal groups, which would be able to rewrite the nation's constitution. The referendum went ahead on 25 April 1999, and was an overwhelming success for Chávez, with 88% of voters supporting the proposal.[3][4] Following this, Chávez called for an election to take place on 25 July 1999, in which the members of the constitutional assembly would be voted into power, and as Bart Jones commented, "The stakes were high. Chávez believed a constitutional assembly controlled by his supporters was the major breakthrough the country needed to end the traditional parties' stronghold on power. Nonetheless, it was not only political supporters of Chávez that believed the assembly was necessarily but also the general public. As a woman in Chávez's home town of Barinas put it on election night, "Democracy is infected. And Chávez is the only antibiotic we have. "[5] The oligarchy, the traditional parties, and much of the media feared it was the final step to establishing a one-man dictatorship."[6]

Former president and Chávez's predecessor Rafael Caldera protested against the constituent assembly, arguing that it violated the 1961 Constitution. Allan Brewer-Carías, a Venezuelan legal scholar and elected member of this assembly, explains that this constitution-making body was an instrument for the gradual dismantling of democratic institutions and values.[7]

Of the 1,171 candidates standing for election to the assembly, over 900 of them were opponents of Chávez. Chávez's supporters won 52% of the vote; despite this, because of voting procedures chosen by the government beforehand, supporters of the new government took 125 seats (95% of the total), including all of those belonging to indigenous tribal groups, whereas the opposition obtained only 6 seats.[3][8] One of the 6 seats was occupied by Professor Allan Brewer-Carías, the most knowledgeable person in the country on the subject of the 1961 Constitution and constitutional history. He was extremely vocal in denouncing and criticizing the abuse that they intended to introduce in the new Constitution. If this new Carta Magna didn’t bring about more backward thinking into the Republic, it’s in large part thanks to Allan Brewer’s work. [9]

The 131 member assembly was composed of 121 belonging to the Chávez's Patriotic Pole, which consisted of the Fifth Republic Movement, Movement for Socialism, Fatherland for All, the Communist Party of Venezuela, People's Electoral Movement and others, 3 indigenous representatives and 6 Democratic Pole and other party members consisting of Acción Democrática, Copei, Project Venezuela and National Convergence.

Setting up the assembly[]

The Assembly convened 3 August 1999. On 12 August 1999, the new constitutional assembly voted to give themselves the power to abolish government institutions and to dismiss officials who were perceived as being corrupt or operating only in their own interests. As Jones noted, "It was a breathtaking move. To its supporters, it could force reforms that had been blocked for years by corrupt politicians and judicial authorities. To its critics, it was an overreach of power and a threat to democracy. The stage was set for a confrontation with the Supreme Court."[10] Indeed, Chávez and his supporters had discussed dissolving both the Supreme Court and the Congress, each of which they believed to be entirely controlled by the oligarchy and the opponents of the Bolivarian movement. The constitutional assembly had the power to perform such an action, and had already fired almost sixty judges whom it identified as being involved in corruption.[11] Nonetheless, the ANC also offered more power to Chávez, it helped him broaden the powers given to the president, and allowed him to call a general election for all public office positions —many of which weren’t controlled at the time by Chávez or the Movimiento Quinta República. [12] Soto believes that the ANC enabled Chávez to "design a genius political strategy to take over all the spaces in the Venezuelan State."[13]

The new constitution included increased protections for indigenous peoples and women, and established the rights of the public to education, housing, healthcare and food. It added new environmental protections, and increased requirements for government transparency. It increased the presidential term from five to six years, allowed people to recall presidents by referendum, and added a new presidential two-term limit. It converted the bicameral legislature which consisted of a Congress with both a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies into a unicameral one that consisted only of a National Assembly.[14][15][16] As a part of the new constitution, the country, which was then officially known as the Republic of Venezuela, was renamed the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (República Bolivariana de Venezuela) at Chávez's request, thereby reflecting the government's ideology of Bolivarianism.[8]

The resulting 1999 Venezuelan Constitution was approved by referendum in December 1999, with the support of nearly 80% of the population.[17]

Indigenous rights[]

The indigenous peoples in Venezuela make up only around 1.5% of the population nationwide, though the proportion is nearly 50% in Amazonas state.[18] Prior to the creation of the 1999 constitution, legal rights for indigenous peoples were increasingly lagging behind other Latin American countries, which were progressively enshrining a common set of indigenous collective rights in their national constitutions.[19] The 1961 constitution had actually been a step backward from the 1947 constitution, and the indigenous rights law foreseen in it languished for a decade, unpassed by 1999.[19]

Ultimately the constitutional process produced "the region's most progressive indigenous rights regime".[20] Innovations included Article 125's guarantee of political representation at all levels of government, and Article 124's prohibition on "the registration of patents related to indigenous genetic resources or intellectual property associated with indigenous knowledge."[20] The new constitution followed the example of Colombia in reserving parliamentary seats for indigenous delegates (three in Venezuela's National Assembly); and it was the first Latin American constitution to reserve indigenous seats in state assemblies and municipal councils in districts with indigenous population.[21]

Notable Assembly members[]

- Luis Miquilena (President)

- Ronald Blanco La Cruz

- José Gregorio Briceño

- Claudio Fermín

- Willian Lara

- Nicolás Maduro

- Alfredo Peña

- Marisabel Rodríguez de Chávez

- Tarek William Saab

- Professor Allan Brewer-Carías

See also[]

- 2017 Constituent Assembly of Venezuela

References[]

- ^ Van Cott (2003:55)

- ^ Van Cott (2003:56)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marcano and Tyszka 2007. p. 130.

- ^ Jones 2007. p. 238.

- ^ Levitsky, Steven, author. How democracies die. ISBN 978-0-241-38135-9. OCLC 1079327788.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jones 2007. p. 239.

- ^ Allan Brewer-Carías, Dismantling Democracy in Venezuela (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 33-35

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones 2007. p. 240.

- ^ Soto, Carlos García (2019-12-15). "The Long Journey of the 1999 Constitution". Caracas Chronicles. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ Jones 2007. p. 241.

- ^ Jones 2007. pp. 245-246.

- ^ Soto, Carlos García (2019-12-15). "The Long Journey of the 1999 Constitution". Caracas Chronicles. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ Soto, Carlos García (2019-12-15). "The Long Journey of the 1999 Constitution". Caracas Chronicles. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ Wilpert 2007. pp. 31-41.

- ^ "Bolivarian Constitution of Venezuela". Embassy of Venezuela in the US. 2000. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- ^ Gregory Wilpert (August 27, 2003). "Venezuela's New Constitution". Venezuela Analysis.

- ^ Kozloff 2006. p. 94.

- ^ Van Cott (2003:52)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Van Cott (2003), "Andean Indigenous Movements and Constitutional Transformation: Venezuela in Comparative Perspective", Latin American Perspectives 30(1), p51

- ^ Jump up to: a b Van Cott (2003:63)

- ^ Van Cott (2003:65)

- Constituent assemblies

- 1999 in Venezuela