Dictatorship

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of forms of government |

|

|

A dictatorship is a form of government characterized by a single leader (dictator) or group of leaders that hold government power promised to the people and little or no toleration for political pluralism or independent media.[2] In most dictatorships, the country's constitution promise citizens rights and the freedom to free and democratic elections; sometimes, it also mentions that all these aforementioned rights will be granted to the people, but this is not always the case. As democracy is a form of government in which "those who govern are selected through periodically contested elections (in years)", dictatorships are not democracies.[2]

With the advent of the 19th and 20th centuries, dictatorships and constitutional democracies emerged as the world's two major forms of government, gradually eliminating monarchies with significant political power, the most widespread form of government in the pre-industrial era. Typically, in a dictatorial regime, the leader of the country is identified with the title of dictator; although, their formal title may more closely resemble something similar to leader. A common aspect that characterized dictatorship is taking advantage of their strong personality, usually by suppressing freedom of thought and speech of the masses, in order to maintain complete political and social supremacy and stability. Dictatorships and totalitarian societies generally employ political propaganda to decrease the influence of proponents of alternative governing systems.[3][4]

Etymology[]

The word dictator comes from the Latin language word dictātor, agent noun from dictare (dictāt-, past participial stem of dictāre dictate v. + -or -or suffix).[5] In Latin use, a dictator was a judge in the Roman Republic temporarily invested with absolute power.

Types[]

A dictatorship is largely defined as a form of government in which absolute power is concentrated in the hands of a leader (commonly identified as a dictator), a "small clique", or a "government organization", and it aims to abolish political pluralism and civilian mobilization.[6] On the other hand, democracy, which is generally compared to the concept of dictatorship, is defined as a form of government in which power belongs to the population and rulers are elected through contested elections.[7][8]

A newer form of government (originating around the early 20th century) commonly linked to the concept of dictatorship is known as totalitarianism. It is characterized by the presence of a single political party and more specifically, by a powerful leader (a real role model) who imposes his personal and political prominence. The two fundamental aspects that contribute to the maintenance of the power are a steadfast collaboration between the government and the police force, and a highly developed ideology. The government has "total control of mass communications and social and economic organizations".[9] According to Hannah Arendt, totalitarianism is a new and extreme form of dictatorship composed of "atomized, isolated individuals".[10] In addition, she affirmed that ideology plays a leading role in defining how the entire society should be organized. According to the political scientist Juan Linz, the distinction between an authoritarian regime and a totalitarian one is that while an authoritarian regime seeks suffocate politics and political mobilization, but totalitarianism seeks to control politics and political mobilization.[11]

However, one of the most recent classifications of dictatorships does not identify totalitarianism as a form of dictatorship. Barbara Geddes's study focuses in how elite-leader and elite-mass relations influence authoritarian politics. Her typology identifies the key institutions that structure elite politics in dictatorships (i.e. parties and militaries). The study is based on and directly related to some factors like the simplicity of the categorizations, cross-national applicability, the emphasis on elites and leaders, and the incorporation of institutions (parties and militaries) as central to shaping politics. According to her, a dictatorial government may be classified in five typologies: military dictatorships, single-party dictatorships, personalist dictatorships, monarchies, and hybrid dictatorships.[10]

Military dictatorships[]

Military dictatorships are regimes in which a group of officers holds power, determines who will lead the country, and exercises influence over policy. High-level elites and a leader are the members of the military dictatorship. Military dictatorships are characterized by rule by a professionalized military as an institution. In military regimes, elites are referred to as junta members, who are typically senior officers (and often other high-level officers) in the military.[10][12] This type of dictatorship was imposed during the 20th century in countries such as, Chile by Augusto Pinochet, Argentina by Jorge Rafael Videla and other leaders, Uruguay by Juan Maria Bordaberry, Paraguay by Alfredo Stroessner, Bolivia by Hugo Banzer, Brazil by Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco. [13]

Single-party dictatorships[]

Single-party dictatorships are regimes in which one party dominates politics. In single-party dictatorships, a single party has access to political posts and control over policy. In single-party dictatorships, party elites are typically members of the ruling body of the party, sometimes called the central committee, politburo, or secretariat. Those groups of individuals control the selection of party officials and "organizes the distribution of benefits to supporters and mobilize citizens to vote and show support for party leaders".[10]

Current one-party states include China, Uganda, Cuba, Eritrea, Laos, North Korea and Vietnam, The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, which is not recognized by the UN, is also a one-party state.

Personalist dictatorships[]

Personalist dictatorships are regimes in which all power lies in the hands of a single individual. Personalist dictatorships differ from other forms of dictatorships in their access to key political positions, other fruits of office, and depend much more on the discretion of the personalist dictator. Personalist dictators may be members of the military or leaders of a political party. However, neither the military nor the party exercises power independently from the dictator. In personalist dictatorships, the elite corps are usually made up of close friends or family members of the dictator. These individuals are all typically handpicked to serve their posts by the dictator.[10][14]

As such dictators favor loyalty over competence and in general distrust intelligentsia, members of the winning coalition often do not possess professional political careers and are ill-equipped to manage the tasks of the office bestowed on them. Without the dictator’s blessing, they would never have acquired a position of power. Once ousted, chances are slim they will maintain their position. The dictator knows this and therefore uses such divide-and-rule tactics to keep their inner circle from coordinating actions (like coups) against them. The result is that such regimes have no internal checks and balances, and are thus unrestrained when exerting repression on their people, making radical shifts in foreign policy, or even starting wars (with other countries.)[15]

According to a 2019 study, personalist dictatorships are more repressive than other forms of dictatorship.[16]

The shift in the power relation between the dictator and its inner circle has severe consequences for the behavior of such regimes as a whole. Many scholars have identified ways in which personalist regimes diverge from other regimes when it comes to their longevity, methods of breakdown, levels of corruption, and proneness to conflicts. The first characteristic that can be identified is their relative longevity. For instance, Mobutu Sese Seko ruled Zaire for 32 years, Rafael Trujillo the Dominican Republic for 31 years and the Somoza family stayed in power in Nicaragua for 42 years.[17] Even when these are extreme examples, personalist regimes, when consolidated, tend to last longer. Barbara Geddes, calculating the lifespans of regimes between 1946 and 2000, found that while military regimes on average stay in power for 8.5 years, personalist regimes survive almost twice as long: on average 15 years. Single-party regimes, on the other hand, used to have a lifespan of nearly 24 years.[18] Monarchies were not included in that research, but a similar study sets their average duration at 25.4 years.[19] This may seem surprising since usually personalist regimes are considered among the most fragile because they do not possess effective institutions nor a significant support base in society. Studies on the probability of their breakdown found mixed results: Compared to other regime types they are most resistant to internal fragmentation, but more vulnerable to external shocks than single-party or military regimes. The second characteristic is how these regimes behave differently regarding growth rates. With the wrong leadership, some regimes squander their country’s economic resources and bring growth to a virtual halt. Without any checks and balances to their rule, such dictators are domestically unopposed when it comes to unleashing repression, or even starting wars.[20]

Monarchic dictatorships[]

Monarchic dictatorships are in regimes in which "a person of royal descent has inherited the position of head of state in accordance with accepted practice or constitution." Regimes are not considered dictatorships if the monarch's role is largely ceremonial, but absolute monarchies, such as Saudi Arabia, can be thought of as hereditary dictatorships. To be considered a dictatorship, political power must have been promised to the people but in reality, is exercised by the monarch for regimes, but since the power of the government was never promised to the people in the first place it is not a dictatorship but an authoritarian government. Elites in monarchies are typically members of the royal family.[10]

Hybrid dictatorships[]

Hybrid dictatorships are regimes that blend qualities of personalist, single-party, and military dictatorships. When regimes share characteristics of all three forms of dictatorships, they are referred to as triple threats. The most common forms of hybrid dictatorships are personalist/single-party hybrids and personalist/military hybrids.[10]

Measuring dictatorships[]

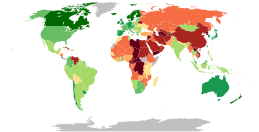

One of the tasks in political science is to measure and classify regimes as either dictatorships or democracies. US based Freedom House, Polity IV and Democracy-Dictatorship Index are three of the most used data series by political scientists.[23]

Generally, two research approaches exist: the minimalist approach, which focuses on whether a country has continued elections that are competitive, and the substantive approach, which expands the concept of democracy to include human rights, freedom of the press, and the rule of law. The Democracy-Dictatorship Index is seen as an example of the minimalist approach, whereas the Polity data series, is more substantive.[24][25][26][27]

History[]

Between the two world wars, three types of dictatorships have been described: constitutional, counterrevolutionary, and fascist. Since World War II, a broader range of dictatorships has been recognized, including Third World dictatorships, theocratic or religious dictatorships, and dynastic or family-based dictatorships.[28]

Dictators in the Roman Empire[]

During the Republican phase of Ancient Rome, a Roman dictator was the special magistrate who held well defined powers, normally for six months at a time, usually in combination with a consulship. [29] [30] Roman dictators were allocated absolute power during times of emergency. In execution, their power was originally neither arbitrary nor unaccountable, being subject to law and requiring retrospective justification. There were no such dictatorships after the beginning of the 2nd century BC, and later dictators such as Sulla and the Roman emperors exercised power much more personally and arbitrarily. A concept that remained anathema to traditional Roman society, the institution was not carried forward into the Roman Empire.

Shoguns in Japan[]

Shogun[31]}} was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country,[32] though during part of the Kamakura period shoguns were themselves figureheads. The office of shogun was in practice hereditary, though over the course of the history of Japan several different clans held the position. Shogun is the short form of Sei-i Taishōgun (征夷大将軍, "Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force Against the Barbarians"),[33] a high military title from the early Heian period in the 8th and 9th centuries; when Minamoto no Yoritomo gained political ascendency over Japan in 1185, the title was revived to regularize his position, making him the first shogun in the usually understood sense.

19th-century Latin American caudillos[]

After the collapse of Spanish colonial rule, various dictators came to power in many liberated countries. Often leading a private army, these caudillos or self-appointed political-military leaders, attacked weak national governments once they controlled a region's political and economic powers, with examples such as Antonio López de Santa Anna in Mexico and Juan Manuel de Rosas in Argentina. Such dictatorships have been also referred to as "personalismos".

The wave of military dictatorships in South America in the second half of the twentieth century left a particular mark on Latin American culture. In Latin American literature, the dictator novel challenging dictatorship and caudillismo is a significant genre. There are also many films depicting Latin American military dictatorships.

Right-wing dictatorships of the 20th century[]

In the first half of the 20th century, right-wing dictatorships appeared in a variety of European countries at the same time as the rise of communism, which are distinct from dictatorships in Latin America and postcolonial dictatorships in Africa and Asia. The main examples of right-wing dictatorship include:

- Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler.

- Empire of Japan which was led by Hideki Tojo and others.

- Prathet Thai under Plaek Phibunsongkhram.

- The Fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini.

- Austrofascist Austria under Engelbert Dollfuss and succeeded by Kurt Schuschnigg.

- Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia under Emil Hácha.

- Slovak Republic under Jozef Tiso.

- Spain under Francisco Franco.

- Portugal under António de Oliveira Salazar.

- South Korea under Park Chung-hee

- France under Philippe Pétain. [34]

- Romania under Ion Antonescu. [35]

- Hungary under Miklós Horthy. [36]

- Greece under Ioannis Metaxas.

- Croatia under Ustashe and Ante Pavelić. [37]

- Indonesia under Suharto

Latin American dictatorships of the 20th century[]

Dictatorships established by Operation Condor[]

During the Cold War, several overthrows of socialist governments in South America were financed and supported by the United States' Central Intelligence Agency. However, the United States had previously made attempts to repress the communists via the "National Security Doctrine" that the United States imposed in the 1950s to indoctrinate the soldiers of countries led by them to confront the alleged "communist threat".

Paraguay under Alfredo Stroessner assumed power in the 1954 coup against President Federico Chávez,[13] which then followed by the Brazilian military dictatorship which seized power in 1964 coup and deposed President João Goulart.[41]

In 1973, the Chilean military dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet seized power after a coup d'état that ended the three-year presidency and ultimately the life of socialist president Salvador Allende. On the same year the Uruguayan civic-military dictatorship seized power from President Juan María Bordaberry. Three years later, the Argentine military junta under Jorge Videla and later Leopoldo Galtieri deposed President Isabel Martínez de Perón.

In 1971, Bolivian general Hugo Banzer deposed socialist president Juan José Torres, who would later be assassinated in Videla's Argentina. Banzer would democratically return to office in 1997. The Peruvian Military Junta in 1968 grabbed power from President Fernando Belaúnde Terry and replaced him with General Juan Velasco Alvarado before he himself was deposed by General Francisco Morales-Bermúdez.[42]

Other dictatorships[]

In 1931, a coup was organized against the government of Arturo Araujo, starting the period known as Military Dictatorship of El Salvador from Civic Directory. The government committed several crimes against humanity, such as La Matanza ( The Massacre in english), a peasant uprising in which the military murdered between 10,000 to 40,000 peasants and civilians, the dictatorship ended in 1979.

From 1942 to 1952 Rafael Leónidas Trujillo ruled Dominican Republic, repressing the Communists and their opponents. Trujillo ordered the assassination of Rómulo Betancourt, who was the founder of Democratic Action, but before he found out about this ambush, Trujillo's plan ended in failure. In October 1937 the Parsley massacre took place in which the main objective was to assassinate immigrants Hatians residing in Dominican Republic, it is estimated that the dead during the massacre were 12,168 dead, by the president Haitian Élie Lescot, 12,136 dead and 2419 injured by Jean Price-Mars, 17,000 dead by Joaquin Balaguer and 35,000 killed by Bernardo Vega. The dictatorship ended when Trujillo was assassinated in 1961 in the city of Santo Domingo.

On November 24, 1948 Venezuelan armed forces took power based on a coup d'état, overthrowing the government of Rómulo Gallegos, who was a president of center left. Subsequently, a board composed of 3 generals was organized, one of them was Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who later became dictator of Venezuela. The dictatorship repressed the Democratic Action and the Communist Party of Venezuela, both from left. led the DSN, which was a military organization Venezuelan that repressed opponents and protesters. Among the cases of crimes against humanity are the death of the Democratic Action politician, who was assassinated while trying to flee from Venezuela. In 1958 an attempt was organized to overthrow , faced with political pressure had to get rid of many of his allies such as . That same year, a movement of civilians and military men joined forces to force Marcos Pérez Jiménez and his most loyal ministers to leave the country. The dictatorship ended when Marcos Pérez Jiménez was exiled from the country, the civilians were To celebrate in the street, the political prisoners were released and the exiles returned to the country, the Venezuelans once again elected Rómulo Betancourt, who had already been president years ago. However, he continued to use the political and economic system of the Jiménez dictatorship.

Although a large part of the Latin American dictatorships were from the political right wing, the Soviet Union supported socialist states in Latin America as well. Cuba under Fidel Castro was a great example of such state. Castro's government was established after the Cuban Revolution, that overthrew the administration of dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959, turning it into the first Socialist State of the Western Hemisphere. In 2008 Castro left power and was replaced by his brother, Raúl.

In 1972, Guillermo Rodriguez Lara established a dictatorial government in Ecuador, and called his government the "Nationalist Revolution"[citation needed]. In 1973, the country entered OPEC. The government also imposed agrarian reforms in practice[citation needed]. Rodriguez Lara's regime was replaced in 1976 by another military junta led by Alfredo Poveda, whose own rule ended in 1979 and was followed by a democratically elected government.

Dictatorships in Africa and Asia after World War II[]

After World War II, dictators established themselves in the several new states of Africa and Asia, often at the expense or failure of the constitutions inherited from the colonial powers. These constitutions often failed to work without a strong middle class or work against the preexisting autocratic rule. Some elected presidents and prime ministers captured power by suppressing the opposition and installing one-party rule and others established military dictatorships through their armies. Whatever their form, these dictatorships had an adverse impact on economic growth and the quality of political institutions.[43] Dictators who stayed in office for a long period of time found it increasingly difficult to carry out sound economic policies.

The often-cited exploitative dictatorship is the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled Zaire from 1965 to 1997, embezzling over $5 billion from his country.[44] Pakistan is another country to have been governed by 3 military dictators for almost 32 years in 7 decades of its existence. Starting with General Muhammad Ayub Khan who ruled from 1958–1969. Next was General Zia-ul-Haq who usurped power in 1977 and held on to power the longest until he died in an air crash in 1988. Ten years after Zia, General Pervez Musharraf got control after defeat against India in the Kargil war. He remained in power for 9 years until 2008.[45] Suharto of Indonesia is another prime example, having embezzled $15-35 billion[46][47] during his 31-year dictatorship known as the New Order. In the Philippines, the conjugal dictatorship[48] of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos embezzled billions of dollars in public funds,[49][50][51] while the nation's foreign debt skyrocketed from $599 million in 1966 to $26.7 billion in 1986, with debt payment being reachable only by 2025.[52] The Marcos dictatorship has been noted for its anti-Muslim killings,[53][54][55][56] political repression, censorship, and human rights violations,[57] including various methods of torture.[58]

Democratization[]

The global dynamics of democratization has been a central question for political scientists.[59][60] The Third Wave Democracy was said to turn some dictatorships into democracies[59] (see also the contrast between the two figures of the Democracy-Dictatorship Index in 1988 and 2008).

One of the rationales that the Bush Administration employed periodically during the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq is that deposing Saddam Hussein and installing a democratic government in Iraq would promote democracy in other Middle Eastern countries.[61] However, according to The Huffington Post, "The 45 nations and territories with little or no democratic rule represent more than half of the roughly 80 countries now hosting U.S. bases. ... Research by political scientist Kent Calder confirms what's come to be known as the "dictatorship hypothesis": The United States tends to support dictators [and other undemocratic regimes] in nations where it enjoys basing facilities."[62]

Theories of dictatorship[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (December 2017) |

Mancur Olson suggests that the emergence of dictatorships can be linked to the concept of "roving bandits", individuals in an atomic system who move from place to place extracting wealth from individuals. These bandits provide a disincentive for investment and production. Olson states that a community of individuals would be served less badly if that bandit were to establish himself as a stationary bandit to monopolize theft in the form of taxes. Except from the community, the bandits themselves will be better served, according to Olson, by transforming themselves into "stationary bandits". By settling down and making themselves the rulers of a territory, they will be able to make more profits through taxes than they used to obtain through plunder. By maintaining order and providing unsolicited protection to the community, the bandits will create an environment in which people can increase their surplus which means a greater taxable base. Thus a potential dictator will have a greater incentive to provide an illusion of security to a given community from which he is extracting taxes and conversely, the unthinking part of the people from whom he extracts the taxes are more likely to produce because they will be unconcerned with potential theft by other bandits. This is the rationale that bandits use in order to explain their transformation from "roving bandits" into "stationary bandits".[63]

See also[]

- Absolute monarchy

- Autocracy

- Authoritarianism

- Benevolent dictatorship

- Civil-military dictatorship

- Constitutional dictatorship

- European interwar dictatorships

- Stalinism

- Maoism

- Juche

- Dictatorship of the bourgeoisie

- Dictatorship of the proletariat

- Despotism

- Elective dictatorship

- Family dictatorship

- How Democracies Die

- Military dictatorship

- Generalissimo

- List of titles used by dictators

- Maximum Leader

- Mobutism

- Nazism

- Fascism

- People's democratic dictatorship

- Right-wing dictatorship

- Selectorate theory

- Strongman

- Supreme leader

- Theocracy

References[]

- ^ Del Testa, David W; Lemoine, Florence; Strickland, John (2003). Government Leaders, Military Rulers, and Political Activists. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-57356-153-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ezrow, Natasha (2011). Dictators and dictatorships : understanding authoritarian regimes and their leaders. Frantz, Erica. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-1602-4. OCLC 705538250.

- ^ Tucker, Robert C. (1965). "The Dictator and Totalitarianism". World Politics. 17 (4): 555–83. doi:10.2307/2009322. JSTOR 2009322. OCLC 4907282504.

- ^ Cassinelli, C. W. (1960). "Totalitarianism, Ideology, and Propaganda". The Journal of Politics. 22 (1): 68–95. doi:10.2307/2126589. JSTOR 2126589. OCLC 6822391923. S2CID 144192403.

- ^ "Oxford English Dictionary, (the definitive record of the English language)".

- ^ Olson, Mancur (1993). "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development". The American Political Science Review. 87 (3): 567–76. doi:10.2307/2938736. JSTOR 2938736. OCLC 5104816959.

- ^ Kurki, Milja (2010). "Democracy and Conceptual Contestability: Reconsidering Conceptions of Democracy in Democracy Promotion" (PDF). International Studies Review. 12. no. 3 (3): 362–86. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2486.2010.00943.x. JSTOR 40931113.

- ^ Bermeo, Nancy (1992). "Democracy and the Lessons of Dictatorship". Comparative Politics. 24 (3): 273–91. doi:10.2307/422133. JSTOR 422133.

- ^ McLaughlin, Neil (2010). "Review: Totalitarianism, Social Science, and the Margins". The Canadian Journal of Sociology. 35 (3): 463–69. doi:10.29173/cjs8876. JSTOR canajsocicahican.35.3.463.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Ezrow, Natasha M; Frantz, Erica (2011). Dictators and dictatorships: understanding authoritarian regimes and their leaders. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-1602-4. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Linz, Juan J (2009). Totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. Boulder, CO: Rienner. ISBN 978-1-55587-866-5. OCLC 985592359.

- ^ Friedrich, Carl (1950). "Military Government and Dictatorship". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 267: 1–7. doi:10.1177/000271625026700102. OCLC 5723774494. S2CID 146698274.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mar Romero (11 August 2019). "La Operación Condor y la persecución de la izquierda en America Latina" (in Spanish). Latin America. EOM. p. elordenmundial.com. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Peceny, Mark (2003). "Peaceful Parties and Puzzling Personalists". The American Political Science Review. 97 (2): 339–42. doi:10.1017/s0003055403000716. OCLC 208155326. S2CID 145169371.

- ^ Van den Bosch, Jeroen J. J., Personalist Rule in Africa and Other World Regions, (London-New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 10-11.

- ^ Frantz, Erica; Kendall-Taylor, Andrea; Wright, Joseph; Xu, Xu (27 August 2019). "Personalization of Power and Repression in Dictatorships". The Journal of Politics. 82: 372–377. doi:10.1086/706049. ISSN 0022-3816. S2CID 203199813.

- ^ Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. A., Verdier, T. (2004) “Kleptocracy and Divide-and-rule: A Model of Personal Rule,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 2(2–3): 163.

- ^ Geddes, B. (2004) “Authoritarian Breakdown,” Revision of “Authoritarian Breakdown: Empirical Test of a Game Theoretic Argument.” pp. 18-19.

- ^ Hadenius, A., Teorell, J. (2007) “Pathways from Authoritarianism,” Journal of Democracy, 18(1): 143–157.

- ^ Van den Bosch, Jeroen J. J., Personalist Rule in Africa and Other World Regions, (London-New York: Routledge, 2021): 13-16

- ^ "Call them ‘Dictators’, not ‘Kings’". Dawn. 28 January 2015.

- ^ "EIU Democracy Index 2020 - World Democracy Report". Economist Intelligence Unit. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ William Roberts Clark; Matt Golder; Sona N Golder (23 March 2012). "5. Democracy and Dictatorship: Conceptualization and Measurement". Principles of Comparative Politics. CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-60871-679-1.

- ^ "Democracy and Dictatorship: Conceptualization and Measurement". cqpress.com. 17 August 2017.

- ^ Møller, Jørgen; Skaaning, Svend-Erik (2012). Requisites of Democracy: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Explanation. Routledge. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-1-136-66584-4.

- ^ Clark, William Roberts; Golder, Matt; Golder, Sona Nadenichek (2009). Principles of comparative politics. CQ Press. ISBN 978-0-87289-289-7.

- ^ Divergent Incentives for Dictators: Domestic Institutions and (International Promises Not to) Torture Appendix "Unlike substantive measures of democracy (e.g., Polity IV and Freedom House), the binary conceptualization of democracy most recently described by Cheibub, Gandhi and Vree-land (2010) focuses on one institution—elections—to distinguish between dictatorships and democracies. Using a minimalist measure of democracy rather than a substantive one better allows for the isolation of causal mechanisms (Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland, 2010, 73) linking regime type to human rights outcomes."

- ^ Frank J. Coppa (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia of Modern Dictators: From Napoleon to the Present. Peter Lang. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8204-5010-0. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

In the period between the two world wars, three types of dictatorships were described by a number of smart people: constitutional, the counterrevolutionary, and the fascist. Many have rightfully questioned the distinctions between these prototypes. In fact, since World War II, we have recognized that the range of dictatorships is much broader than earlier posited and it includes so-called Third World dictatorships in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East and religious dictatorships....They are also family dictatorships ....

- ^ Alfredo Serra (25 February 2018). "Delirio, locura y crímenes de Caligula, el más cruel de los emperadores romanos". Caligula's crimes (in Spanish). Argentina. infobae. p. infobae.com. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Calígula, el césar al que todo estaba permitido" [Caligula, the Caesar to whom everything was allowed] (in Spanish). 8 June 2015: historia.nationalgeographic.com.es. Retrieved 28 January 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Shogun". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ The Modern Reader's Japanese-English Character Dictionary, ISBN 0-8048-0408-7

- ^ "Was Vichy France a Puppet Government or a Willing Nazi Collaborato?" (History). 9 November 2017. p. smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Ruler of Romania "Ion Antonescu"". p. britannica.com. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "The Horthy Era (1920 - 1944)" (History). p. The Orange Files. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Ante Pavelic, Croatian War Criminal" (Biography). 4 October 2019. p. thoughtco.com. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Maxwell, Kenneth (2004). "The Case of the Missing Letter in Foreign Affairs: Kissinger, Pinochet and Operation Condor". David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University.

- ^ Dalenogare Neto, Waldemar (30 March 2020). "Os Estados Unidos e a Operação Condor". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ McSherry, J. Patrice (1999). "Operation Condor: Clandestine Inter-American System". Social Justice. 26 (4 (78)): 144–174. ISSN 1043-1578. JSTOR 29767180.

- ^ "Dictadura de Brasil" (History) (in Spanish): rioandlearn.com. Retrieved 26 January 2021. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jacqueline Fowks (18 January 2017). "Italia condena a cadena perpetua a un ex dictador peruano por el Plan Condor". elpais.com (in Spanish). Spain: El Pais. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Papaioannou, Kostadis; vanZanden, Jan Luiten (2015). "The Dictator Effect: How long years in office affect economic development". Journal of Institutional Economics. 11 (1): 111–39. doi:10.1017/S1744137414000356. S2CID 154309029.

- ^ "Mobutu dies in exile in Morocco". CNN. 7 September 1997.

- ^ "A brief history of military rule in Pakistan". D+C. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Global Corruption Report 2004: Political Corruption by Transparency International - Issuu. Pluto Press. 2004. p. 13. ISBN 0-7453-2231-X – via Issuu.com.

- ^ "Suharto tops corruption rankings". BBC News. 25 March 2004. Retrieved 4 February 2006.

- ^ Mijares, Primitivo. The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos, Union Square Publishing, Manila, 1976. ISBN 1-141-12147-6.

- ^ McGeown, Kate (25 January 2013). "What happened to the Marcos fortune?". BBC News.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Imelda Marcos sentenced to 42 years for £154m fraud". 9 November 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "[ANALYSIS] Just how bad was corruption during the Marcos years?". Rappler.

- ^ Inquirer, Philippine Daily (18 March 2016). "'We'll pay Marcos debt until 2025'". INQUIRER.net.

- ^ "Murad: Marcos regime's genocidal war vs. Muslims drove us to armed struggle". GMA News Online.

- ^ "FALSE: 'No massacres' during Martial Law". Rappler.

- ^ "Fighting and talking: A Mindanao conflict timeline". GMA News and Public Affairs. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ Aquino Jr., Benigno S. (28 March 1968). "Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil?". Delivered at the Legislative Building, Manila, on 28 March 1968. Government of the Philippines.

- ^ To Islands Far Away: the Story of the Thomasites and Their Journey to the Philippines. Manila: US Embassy. 2001.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Worse than death: Torture methods during martial law". Rappler.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Samuel P. Huntington (6 September 2012). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late 20th Century. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8604-7.

- ^ Nathan J. Brown (2011). The Dynamics of Democratization: Dictatorship, Development, and Diffusion. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0088-4.

- ^ Wright, Steven. The United States and Persian Gulf Security: The Foundations of the War on Terror, Ithaca Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-86372-321-6

- ^ "How U.S. Military Bases Back Dictators, Autocrats, And Military Regimes". The Huffington Post]. 16 May 2017.

- ^ Olson, Mancur (1993). "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development". American Political Science Review. 87 (3): 567–576. doi:10.2307/2938736. JSTOR 2938736.

Further reading[]

- Behrends, Jan C. Dictatorship: Modern Tyranny Between Leviathan and Behemoth, in Docupedia Zeitgeschichte, 14 March 2017

- Dikötter, Frank. How to Be a Dictator: The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century (2019) scholarly analysis of eight despots: Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin and Mao, as well as Kim Il-sung of North Korea; François Duvalier, or Papa Doc, of Haiti; Nicolae Ceaușescu of Romania; and Mengistu Haile Mariam of Ethiopia. online review; also excerpt

- William J. Dobson (2013). The Dictator's Learning Curve: Inside the Global Battle for Democracy. Anchor. ISBN 978-0-307-47755-2.

- Finchelstein, Federico. The ideological origins of the dirty war: Fascism, populism, and dictatorship in twentieth century Argentina (Oxford UP, 2017).

- Fraenkel, Ernst, and Jens Meierhenrich. The dual state: A contribution to the theory of dictatorship. (Oxford UP, 2018).

- Friedrich, Carl J.; Brzezinski, Zbigniew K. (1965). Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy (2nd ed.). Praeger.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce; Smith, Alastair; Siverson, Randolph M.; Morrow, James D. (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63315-4.

- Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith (2011). The Dictator's Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics. Random House. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-61039-044-6. OCLC 701015473.

- Ridenti, Marcelo. "The Debate over Military (or Civilian‐Military?) Dictatorship in Brazil in Historiographical Context." Bulletin of Latin American Research 37.1 (2018): 33–42.

- Ringen, Stein. The perfect dictatorship: China in the 21st century (Hong Kong UP, 2016).

- Ward, Christoper Edward, ed. The Stalinist Dictatorship (Routledge, 2018).

- Dictatorship

- Authoritarianism

- Oligarchy