2017 Dutch general election

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 150 seats in the House of Representatives 76 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

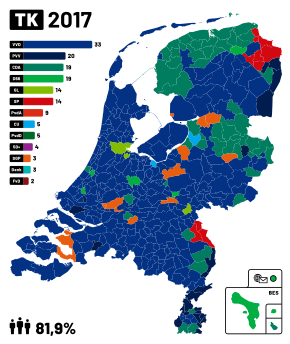

| Turnout | 81.9% ( | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General elections were held in the Netherlands on Wednesday 15 March 2017 to elect all 150 members of the House of Representatives.[1]

The incumbent government of Prime Minister Mark Rutte was the first to serve a full term since 2002. The previous elections in 2012 had resulted in a ruling coalition of his People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) and the Labour Party (PvdA). Because the second Rutte cabinet lacked a majority in the Senate, it relied on the support of Democrats 66 (D66), the Christian Union (CU) and the Reformed Political Party (SGP).

The VVD lost seats but remained the largest party, while the PvdA saw a massive loss in vote share and seats,[2] failing to win a single municipality for the first time in the party's history.[3] The Party for Freedom (PVV) made gains to reach second place, with the CDA, D66 and GroenLinks also increasing their number of seats. It was clear that at least four partners would be needed for a coalition with a parliamentary majority.[2] The official election results were certified and published on 21 March.[4] The elected MPs took their seats on 23 March.[5]

Electoral system and organisation[]

The House of Representatives (Dutch: Tweede Kamer) is composed of 150 seats elected by proportional representation in a single nationwide constituency, with a legal threshold of 1 full seat (0.67%), and residuals assigned by the D'Hondt method.[6][7] The Senate is indirectly elected by the States-Provincial.

Electronic voting has been banned since 2007; votes must be cast with a red pencil.

Following reports from the General Intelligence and Security Service (Algemene Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdienst, AIVD) that Russian hacking groups Fancy Bear and Cozy Bear had made several attempts to hack into Dutch ministries, including the Ministry of General Affairs, to gain access to secret government documents.[8] Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations Ronald Plasterk announced that votes for the election would therefore be processed by hand,[9] although that decision was later reversed.[10]

The election was also seen as an indication of interest in the national political system in the Caribbean Netherlands, after the low turnout seen there in the 2012 election.[11]

Participating parties[]

Campaign[]

The 2017 Dutch–Turkish diplomatic incident happened less than a week before the election; it was speculated that this benefited the Prime Minister's party (VVD), as Rutte's response to the incident was well received.[14]

Debates[]

| Dutch general election debates, 2017 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Organisers | Venue | P Present NI Non-invitee A Absent invitee | Note | |||||||||

| Roemer | Krol | Thieme | Klaver | Asscher | Pechtold | Rutte | Segers | Buma | Wilders | ||||

| 26 February | RTL Nieuws | De Rode Hoed | P | NI | NI | P | P | P | A | NI | P | A | [15] |

| 5 March | BNR Nieuwsradio, RTL Nieuws, Elsevier | Carré Theatre | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | A | P | A | [16] |

| 13 March | EenVandaag | Erasmus University | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | P | NI | NI | P | [17] |

| 14 March | NOS | Binnenhof | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | [18] |

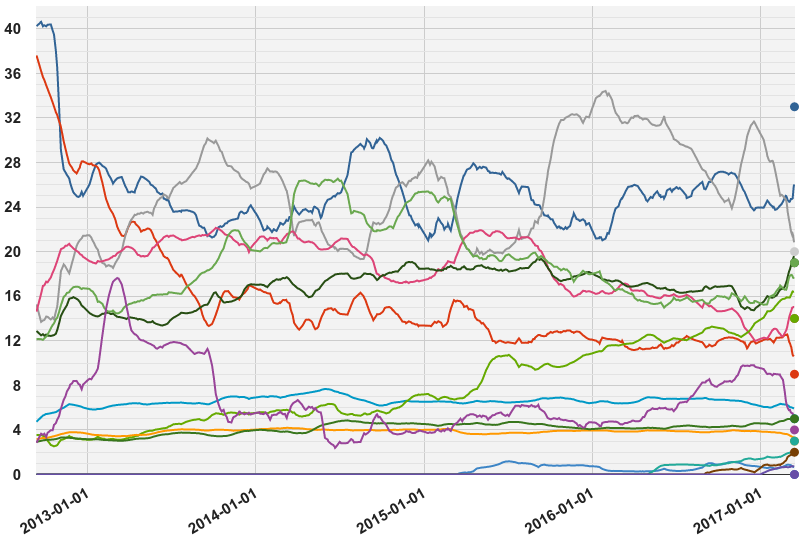

Opinion polls[]

Polls showed a precipitous collapse for both the VVD and PvdA following their decision to form a coalition government together after the 2012 elections, with support for the latter splitting among other left-wing or liberal parties. As with other right-wing populist parties, the Party for Freedom (PVV) rose in polls during the European migrant crisis, with the party topping polls from September 2015 through to late February 2017. However, in the relative absence of Geert Wilders during the campaign – notably refusing to participate in both RTL debates – support for the PVV collapsed, and the VVD secured a narrow lead in the final weeks before the election.

The seat projections in the graphs below are continuous from September 2012 (the last general election) up to the current date. Each colored line specifies a political party; numbers on the vertical axis represent numbers of seats. These seat estimates are derived from estimates by Peilingwijzer ("polling indicator") by Tom Louwerse, a professor of political science at Leiden University; they are not strictly polling averages, but the results of a model calculating a "trajectory" for each party based on changes in support over time between polls conducted by I&O Research, Ipsos, TNS NIPO, LISS panel, Peil, and De Stemming, and adjusting for the house effects of each individual pollster.[19]

Results[]

Preliminary results were published on 15 March, and the official result was announced at 16:00 CET on 21 March.[4]

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People's Party for Freedom and Democracy | 2,238,351 | 21.29 | 33 | −8 | |

| Party for Freedom | 1,372,941 | 13.06 | 20 | +5 | |

| Christian Democratic Appeal | 1,301,796 | 12.38 | 19 | +6 | |

| Democrats 66 | 1,285,819 | 12.23 | 19 | +7 | |

| GroenLinks | 959,600 | 9.13 | 14 | +10 | |

| Socialist Party | 955,633 | 9.09 | 14 | −1 | |

| Labour Party | 599,699 | 5.70 | 9 | −29 | |

| Christian Union | 356,271 | 3.39 | 5 | 0 | |

| Party for the Animals | 335,214 | 3.19 | 5 | +3 | |

| 50PLUS | 327,131 | 3.11 | 4 | +2 | |

| Reformed Political Party | 218,950 | 2.08 | 3 | 0 | |

| DENK | 216,147 | 2.06 | 3 | New | |

| Forum for Democracy | 187,162 | 1.78 | 2 | New | |

| VoorNederland | 38,209 | 0.36 | 0 | New | |

| Pirate Party | 35,478 | 0.34 | 0 | 0 | |

| Artikel 1 | 28,700 | 0.27 | 0 | New | |

| Nieuwe Wegen | 14,362 | 0.14 | 0 | New | |

| Entrepreneurs Party | 12,570 | 0.12 | 0 | New | |

| Lokaal in de Kamer | 6,858 | 0.07 | 0 | New | |

| Non-Voters | 6,025 | 0.06 | 0 | New | |

| Civil Movement | 5,221 | 0.05 | 0 | New | |

| GeenPeil | 4,945 | 0.05 | 0 | New | |

| Jesus Lives | 3,099 | 0.03 | 0 | New | |

| Free-Minded Party | 2,938 | 0.03 | 0 | New | |

| Libertarian Party | 1,492 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | |

| MenS–BIP–V-R | 726 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | |

| StemNL | 527 | 0.01 | 0 | New | |

| Free Democratic Party | 177 | 0.00 | 0 | New | |

| Total | 10,516,041 | 100.00 | 150 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 10,516,041 | 99.55 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 47,415 | 0.45 | |||

| Total votes | 10,563,456 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 12,893,466 | 81.93 | |||

| Source: Kiesraad | |||||

By province[]

| Province | VVD | PVV | CDA | D66 | GL | SP | PvdA | CU | PvdD | 50+ | SGP | DENK | FvD | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.6 | 12.8 | 14.4 | 10.2 | 7.8 | 11.9 | 8.6 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | |

| 20.7 | 14.7 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.0 | |

| 17.0 | 11.2 | 18.9 | 9.7 | 8.4 | 11.1 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 1.5 | |

| 20.9 | 11.7 | 13.9 | 11.9 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.1 | |

| 13.9 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 12.6 | 11.9 | 13.9 | 8.3 | 6.0 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.4 | |

| 17.9 | 19.6 | 14.9 | 10.6 | 6.8 | 13.7 | 4.0 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.2 | |

| 24.1 | 14.6 | 13.3 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 12.3 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | |

| 23.2 | 10.8 | 8.0 | 14.8 | 12.3 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | |

| 18.7 | 11.6 | 19.8 | 10.6 | 7.0 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 | |

| 22.1 | 14.5 | 10.2 | 12.1 | 8.7 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 1.6 | |

| 22.7 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 15.3 | 11.7 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 | |

| 19.7 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 8.1 | 6.2 | 9.5 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 9.5 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.2 | |

| 12.4 | 4.2 | 23.6 | 25.9 | 8.9 | 5.5 | 7.1 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.4 |

Government formation[]

The election resulted in a House of Representatives where at least four parties would be required to form a coalition with a majority (76 seats). Media sources speculated that incumbent Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the VVD would seek to form a government with the support of the centre-right CDA and liberal D66. CU was thought to be the most likely candidate to be the fourth member of the coalition.[21] Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport, Edith Schippers, was selected by the VVD to serve as the party's informateur on 16 March and appointed by Speaker of the House Khadija Arib, seeking to determine whether Jesse Klaver of GroenLinks solely desired a left-wing government, or instead simply viewed the VVD as an unlikely coalition partner. Similarly, talks with Emile Roemer of the Socialist Party (SP), who repeatedly stated during the campaign that his party would not govern with the VVD, remained a possibility.[22]

The leaders of D66, CDA, PvdA, VVD, SP, GroenLinks, and CU stated that they would not enter a coalition with the PVV,[23][24][25][26][27][28][29] and Roemer has also said that the SP will not join a coalition with the VVD.[30]

The first proposed coalition was one involving the VVD-CDA-D66 and GroenLinks. This was the preferred coalition of Alexander Pechtold, Lodewijk Asscher and Gert-Jan Segers, while Jesse Klaver continued to argue that the major policy differences between GL and the VVD would make a coalition difficult.[31] Nevertheless, the four parties began more serious negotiations toward a coalition agreement. Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (NOS) reported that "labour market reform, investment in law enforcement and additional money for nursing homes" would be areas of agreement between the parties, while "refugee policy, income distribution, climate and medical ethics issues are potential stumbling blocks".[32]

On 15 May, talks on the proposed four-way VVD-CDA-D66-GL coalition failed. It was reported that the main dispute concerned immigration, but GL leader Jesse Klaver cited climate issues and income differences as other issues where the parties disagreed. The end of the talks was reported to be a consensus decision, with no party blaming any others.[33][34]

Coalition talks were reported to be at an impasse, with the VVD and CDA favouring a coalition with the CU, D66 favouring a coalition with either PvdA or SP, SP being absolutely opposed to a coalition with the VVD, CDA being opposed to a coalition without the VVD, PvdA rejecting any coalition, and all parties with more than five seats rejecting a coalition with the PVV. D66 said that it would consider a coalition with the CU very difficult due to disagreements on medical-ethical issues such as doctor-assisted suicide, due to the lack of representation of the political left within that coalition, and due to the small majority of one seat in both chambers, which could make for an unstable coalition.[35][36]

In late June 2017, discussions began again between VVD, D66, CDA and CU under the lead of new informateur Herman Tjeenk Willink. After a three-week summer break, talks resumed on 9 August 2017, and were reported to be close to a conclusion due to representatives of unions and employers’ organizations joining the discussions, which typically happens near the end of such negotiations.[37][38] In September 2017, a budget deal compromise was reached allowing the coalition talks to continue. While still 'close to conclusion', it appeared likely that the talks about government formation would exceed the record since World War II of 208 days set in 1977.[39] After 208 days of negotiations, the VVD, D66, CDA and CU agreed to a coalition under a third informateur, Gerrit Zalm,[40][41][42] and all members of the House of Representatives of the involved parties approved the agreement on 9 October 2017.[43] On 26 October the new cabinet was formally installed 225 days after the elections, setting a record for the longest cabinet formation in history.

See also[]

- 2016 Labour Party leadership election

- 2017 Dutch–Turkish diplomatic incident

- List of members of the House of Representatives of the Netherlands, 2017–2021

Further reading[]

- Mathilde M. van Ditmars, Nicola Maggini & Joost van Spanje (2019) Small winners and big losers: strategic party behaviour in the 2017 Dutch general election, West European Politics

References[]

- ^ "Verkiezingskalender". Kiesraad. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ a b Mehreen Khan (16 March 2017). "Dutch election: everything you need to know as tricky coalition talks loom". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "PvdA in geen enkele gemeente de grootste". Financieele Dagblad. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Kerngegevens Tweede Kamerverkiezingen 2017". Kiesraad. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ "Tweede Kamerverkiezingen 2017". Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Act of 28 September 1989 containing new provisions governing the franchise and elections (Elections Act)" (PDF). Government of the Netherlands. 29 October 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Andeweg, Rudy (2005). "The Netherlands: The Sanctity of Proportionality". In Gallagher, Michael; Mitchell, Paul (eds.). The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925756-6.

- ^ Huib Modderkolk (4 February 2017). "Russen faalden bij hackpogingen ambtenaren op Nederlandse ministeries". Volkskrant. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Peter Cluskey (3 February 2017). "Dutch opt for manual count after reports of Russian hacking". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Huib Modderkolk (3 March 2017). "Plasterk draait: tóch stemsoftware bij verkiezingen". de Volkskrant.

- ^ "Verkiezingen Caribische graadmeter". Telegraaf. 15 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "28 partijen nemen deel aan Tweede Kamerverkiezing". Kiesraad. 3 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Persberichten van Lokaal in de Kamer". Lokaal in de Kamer. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Tobias den Hartog (14 March 2017). "PVV zakt flink weg in peilingen, VVD profiteert". Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Rode Hoed Debat scoort ondanks Boer Zoekt Vrouw". Mediacourant. 27 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Carré-debat – De enige politieke arena zonder theater". Carré-debat. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Confrontatie Rutte en Wilders in EenVandaag-debat". EenVandaag. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Loting NOS-verkiezingsdebatten verricht". NOS. 2 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Tom Louwerse. "Peilingwijzer: Methode". Peilingwijzer. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Tweede Kamer 15 maart 2017". Kiesraad (in Dutch). Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ "Dutch election: Wilders defeat celebrated by PM Rutte". BBC News. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Nederland Kiest: 'formatie wordt moeilijk, moeilijk, moeilijk'". NOS. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Wilders: liever een coalitie dan een revolte". NOS. 2 February 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Buma weigert regeren met PVV nog steeds". Telegraaf. 18 October 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "PvdA-voorzitter Spekman: Henk en Mark, zeg nee tegen de PVV". NOS. 14 January 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Rutte: kans op regering VVD met PVV is nul". NOS. 15 January 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Sasha Kester (14 January 2017). "Roemer sluit samenwerking met VVD uit en roept PvdA op hetzelfde te doen". Volkskrant. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Klaver sluit VVD niet uit, PVV wel". Telegraaf. 15 January 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "ChristenUnie sluit samenwerking met PVV uit". Groot Nieuws Radio. 23 January 2017. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Edwin van der Aa; Hans van Soest (14 January 2017). "Emile Roemer sluit VVD uit". Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Vries, Joost de (20 March 2017). "Van middenkabinet tot 'christelijk progressief', alle formatiewensen op een rij - Binnenland - Voor nieuws, achtergronden en columns". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ "Formatie dag 8: de onderhandelingen gaan beginnen". NOS (in Dutch). 23 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Dutch coalition talks failed say officials, (in English) politico.eu.

- ^ BBC News, Europe.

- ^ Geen kans op slagen met CU (in Dutch), telegraaf.nl.

- ^ Formatie in impassie: D66 nog geen zin in CU (in Dutch), nrc.nl, 2017.05.18.

- ^ Dutch government talks near finish line Politico 4 August 2017.

- ^ Talks to form Dutch govt kick off again after break Yahoo News 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Dutch budget deal prevents collapse of shaky coalition". The Irish Times. 13 September 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "208 Days to Forge Four-Party Coalition Dutch Government". The Australian. 10 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ Kroet, Cynthia (9 October 2017). "Dutch Coalition Partners Agree on Government Deal, Seek Party Backing". Politico. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ Henley, Jon (9 October 2017). "Dutch Parties Agree Coalition Government After a Record 208 Days". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ Kroet, Cynthia (10 October 2017). "Dutch Government Coalition Deal Receives Parliamentary Backing". Politico. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

External links[]

Media related to Dutch general elections 2017 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dutch general elections 2017 at Wikimedia Commons

- General elections in the Netherlands

- 2017 elections in the Netherlands

- 2017 in the Netherlands

- March 2017 events in Europe

- 2017 elections in Europe

- Elections in Bonaire

- Elections in Sint Eustatius

- Elections in Saba

- 2017 elections in the Caribbean