A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

| A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Georges Seurat |

| Year | 1884–1886 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Subject | People relaxing at la Grande Jatte, Paris |

| Dimensions | 207.6 cm × 308 cm (81.7 in × 121.25 in) |

| Location | Art Institute of Chicago |

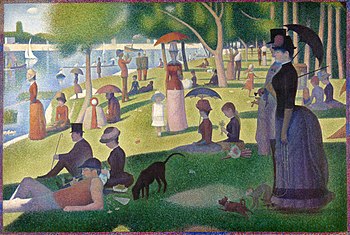

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (French: Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte), painted from 1884 to 1886 and in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, is Georges Seurat's most famous work.[1] A leading example of pointillist technique, executed on a large canvas, it is a founding work of the neo-impressionist movement. Seurat's composition includes a number of Parisians at a park on the banks of the River Seine.

Background[]

In 1879 Georges Seurat enlisted as a soldier in the French army and was back home by 1880. Later, he ran a small painter's studio in Paris, and in 1883 showed his work publicly for the first time. The following year, Seurat began to work on La Grande Jatte and exhibited the painting in the spring of 1886 with the Impressionists.[2] With La Grande Jatte, Seurat was immediately acknowledged as the leader of a new and rebellious form of Impressionism called Neo-Impressionism.[3]

Seurat painted A Sunday Afternoon between May 1884 and March 1885, and from October 1885 to May 1886,[4] focusing meticulously on the landscape of the park. He reworked the original and completed numerous preliminary drawings and oil sketches. He sat in the park, creating numerous sketches of the various figures in order to perfect their form. He concentrated on issues of colour, light, and form. The painting is approximately 2 by 3 meters (7 by 10 feet) in size.

Inspired by optical effects and perception inherent in the color theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood and others, Seurat adapted this scientific research to his painting.[5] Seurat contrasted miniature dots or small brushstrokes of colors that when unified optically in the human eye were perceived as a single shade or hue. He believed that this form of painting, called Divisionism at the time (a term he preferred)[6] but now known as Pointillism, would make the colors more brilliant and powerful than standard brushstrokes. The use of dots of almost uniform size came in the second year of his work on the painting, 1885–86. To make the experience of the painting even more vivid, he surrounded it with a frame of painted dots, which in turn he enclosed with a pure white, wooden frame, which is how the painting is exhibited today at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Island of la Grande Jatte is located at the very gates of Paris, lying in the Seine between Neuilly and Levallois-Perret, a short distance from where La Défense business district currently stands. Although for many years it was an industrial site, it is today the site of a public garden and a housing development. When Seurat began the painting in 1884, the island was a bucolic retreat far from the urban center.

The painting was first exhibited at the eighth (and last) Impressionist exhibition in May 1886, then in August 1886, dominating the second Salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, of which Seurat had been a founder in 1884.[7] Seurat was extremely disciplined, always serious, and private to the point of secretiveness—for the most part, steering his own steady course. As a painter, he wanted to make a difference in the history of art and with La Grand Jatte, many say that he succeeded.[8]

Interpretation[]

Seurat's painting was a mirror impression of his own painting, Bathers at Asnières, completed shortly before, in 1884. Whereas the bathers in that earlier painting are doused in light, almost every figure on La Grande Jatte appears to be cast in shadow, either under trees or an umbrella, or from another person. For Parisians, Sunday was the day to escape the heat of the city and head for the shade of the trees and the cool breezes that came off the river. And at first glance, the viewer sees many different people relaxing in a park by the river. On the right, a fashionable couple, the woman with the sunshade and the man in his top hat, are on a stroll. On the left, another woman who is also well dressed extends her fishing pole over the water. There is a small man with the black hat and thin cane looking at the river, and a white dog with a brown head, a woman knitting, a man playing a horn, two soldiers standing at attention as the musician plays, and a woman hunched under an orange umbrella. Seurat also painted a man with a pipe, a woman under a parasol in a boat filled with rowers, and a couple admiring their infant child.[9]

Some of the characters are doing curious things. The lady on the right side has a monkey on a leash. A lady on the left near the river bank is fishing. The area was known at the time as being a place to procure prostitutes among the bourgeoisie, a likely allusion of the otherwise odd "fishing" rod. In the painting's center stands a little girl dressed in white (who is not in a shadow), who stares directly at the viewer of the painting. This may be interpreted as someone who is silently questioning the audience: "What will become of these people and their class?" Seurat paints their prospects bleakly, cloaked as they are in shadow and suspicion of sin.[10]

In the 1950s, historian and Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch drew social and political significance from Seurat's La Grande Jatte. The historian's focal point was Seurat's mechanical use of the figures and what their static nature said about French society at the time. Afterward, the work received heavy criticism by many that centered on the artist's mathematical and robotic interpretation of modernity in Paris.[9]

According to historian of Modernism William R. Everdell:

Seurat himself told a sympathetic critic, Gustave Kahn, that his model was the Panathenaic procession in the Parthenon frieze. But Seurat didn't want to paint ancient Athenians. He wanted 'to make the moderns file past ... in their essential form.' By 'moderns' he meant nothing very complicated. He wanted ordinary people as his subject, and ordinary life. He was a bit of a democract—a "Communard," as one of his friends remarked, referring to the left-wing revolutionaries of 1871; and he was fascinated by the way things distinct and different encountered each other: the city and the country, the farm and the factory, the bourgeois and the proletarian meeting at their edges in a sort of harmony of opposites.[11]

The border of the painting is, unusually, in inverted color, as if the world around them is also slowly inverting from the way of life they have known. Seen in this context, the boy who bathes on the other side of the river bank at Asnières appears to be calling out to them, as if to say, "We are the future. Come and join us".[10]

Painting materials[]

Seurat painted the La Grande Jatte in three distinct stages.[12] In the first stage, which was started in 1884, Seurat mixed his paints from several individual pigments and was still using dull earth pigments such as ochre or burnt sienna. In the second stage, during 1885 and 1886, Seurat dispensed with the earth pigments and also limited the number of individual pigments in his paints. This change in Seurat's palette was due to his application of the advanced color theories of his time. His intention was to paint small dots or strokes of pure color that would then mix on the retina of the beholder to achieve the desired color impression instead of the usual practice of mixing individual pigments.

Seurat's palette consisted of the usual pigments of his time[13][14] such as cobalt blue, emerald green and vermilion. Additionally, Seurat used then new pigment zinc yellow (zinc chromate), predominantly for yellow highlights in the sunlit grass in the middle of the painting but also in mixtures with orange and blue pigments. In the century and more since the painting's completion, the zinc yellow has darkened to brown—a color degeneration that was already showing in the painting in Seurat's lifetime.[15] The discoloration of the originally bright yellow zinc yellow (zinc chromate) to brownish color is due to the chemical reaction of the chromate ions to orange-colored dichromate ions.[16] In the third stage during 1888–89 Seurat added the colored borders to his composition.

The results of investigation into the discoloration of this painting have been combined with further research into natural aging of paints to digitally rejuvenate the painting.[17][18]

Acquisition by the Art Institute of Chicago[]

In 1923, Frederic Bartlett was appointed trustee of the Art Institute of Chicago. He and his second wife, Helen Birch Bartlett, loaned their collection of French Post-Impressionist and Modernist art to the museum. It was Mrs. Bartlett who had an interest in French and avant-garde artists and influenced her husband's collecting tastes. Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte was purchased on the advice of the Art Institute of Chicago's curatorial staff in 1924.[19]

In conceptual artist Don Celender's 1974–75 book Observation and Scholarship Examination for Art Historians, Museum Directors, Artists, Dealers and Collectors, it is claimed that the institute paid $24,000 for the work[19][20] (over $354,000 in 2018 dollars[21]).

In 1958, the painting was loaned out for the only time: to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. On 15 April 1958, a fire there, which killed one person on the second floor of the museum, forced the evacuation of the painting, which had been on a floor above the fire, to the Whitney Museum, which adjoined MoMA at the time.[22]

In popular culture[]

The May 1976 issue of Playboy magazine featured Nancy Cameron—Playmate of the Month in January 1974—on its cover, superimposed on the painting in similar style. The often hidden bunny logo was disguised as one of the millions of dots.[23]

The painting is the basis for the 1984 Broadway musical Sunday in the Park with George by Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine, which tells a fictionalized story of the painting's creation. Subsequently, the painting is sometimes referred to by the misnomer "Sunday in the Park".

The painting is prominently featured in the 1986 comedy film Ferris Bueller's Day Off, in a scene later parodied, among others, in Looney Tunes: Back in Action, Family Guy, and Muppet Babies.[citation needed]

In the Simpsons episode "Mom and Pop Art" (10x19), Barney Gumble offers to pay for a beer with a handmade reproduction of the painting. The painting is also parodied in the picnic scene at the end of the episode "Super Franchise Me" (26x3).

In Topiary Park (formerly Old Deaf School Park) in Columbus, Ohio, sculptor James T. Mason re-created the painting in topiary form;[24] the installation was completed in 1989.

The painting was the inspiration for a commemorative poster printed for the 1993 Detroit Belle Isle Grand Prix, with racing cars and the Detroit skyline added.

In 2011, the cast of the US version of The Office re-created the painting for a poster to promote the show's seventh-season finale.[25]

The cover photo of the June 2014 edition of San Francisco magazine, "The Oakland Issue: Special Edition", features a scene on the shore of Lake Merritt that re-creates the poses of the figures in Seurat's painting.[26]

Related works by Seurat[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Study for La Grand Jatte

Die Insel La Grande Jatte mit Ausflüglern, 1884

Paysage et personnages, 1884–85

Groupe de personnages, 1884–85

Esquisse d'ensemble, 1884–85

Femmes au bord de l'eau, 1885–86

Models (Les Poseuses) 1886-1888

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Seurat, Georges. "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Janis Tomlinson, ed., Readings in Nineteenth-Century Art, 1996

- ^ Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Nineteenth-Century European Art, 2012 (3rd Edition)

- ^ H. Dorra and J. Rewald, Seurat, Paris, 1960, p. 156.

- ^ Robert Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1968, Library of Congress Card Catalogue Number: 68-16803

- ^ Kathryn Calley Galitz (2007). Masterpieces of European Painting, 1800–1920, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.). p. 177. ISBN 978-1-58839-240-4.

- ^ Exhibition History

- ^ Herbert, Robert L., Neil Harris, and Georges Seurat. Seurat and the making of La Grande Jatte. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago in association with the University of California Press, 2004. Print.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burleigh, Robert, Seurat and La Grande Jatte: connecting the dots, New York: H.N. Abrams in association with the Art Institute of Chicago, 2004. Print

- ^ Jump up to: a b BBC, The Private Life of a Masterpiece (2005) Series 4, Georges Seurat: A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

- ^ William R. Everdell, The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth Century Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 66-7.

- ^ Inge Fiedler, La Grande Jatte: A Study of the Painting Materials, in Robert L. Herbert, Douglas W. Druick, Gloria Groom, Seurat and the Making of La Grande Jatte, University of California, 2004

- ^ Inge Fiedler, A Technical Evaluation of the Grande Jatte, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2, The Grande Jatte at 100 (1989), pp. 173-179+244-245

- ^ Georges Seurat, 'Sunday afternoon on La Grande Jatte', ColourLex

- ^ Gage, John (1993). Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 220, 224..

- ^ Casadio, F., I. Fiedler, K. A. Gray, and R. Warta. Deterioration of zinc potassium chromate pigments: elucidating the effects of paint composition and environmental conditions on chromatic alteration. In ICOM-CC 15th Triennial Conference Preprints, New Delhi, 22–26 September 2008, ed. J. Bridgland, 572–580. Paris: International Council of Museums.

- ^ Berns, Roy S. (2006). "Rejuvenating the color palette of Georges Seurat'sA Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884: A simulation". Color Research & Application. 31: 278–293. doi:10.1002/col.20223.

- ^ Berns, R.S. Rejuvenating Seurat’s Palette Using Color and Imaging Science: A Simulation, Website of R.S. Berns at Rochester Institute of Technology

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Art Institute of Chicago, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884". Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Celender, Don (1974–75). Observation and Scholarship Examination for Art Historians, Museum Directors, Artists, Dealers, and Collectors. Publication was produced for an exhibition held at the O.K. Harris Gallery, 383 West Broadway, New York, from 7 to 28 December 1974. pp. Question: Page 5, Answer: Page 23.

- ^ CPI Inflation Calculator

- ^ New York Times, Fire in Modern Museum; Most Art Safe; 6 Canvases Burned, Seurat's Removed, 16 April 1958

- ^ Lucass Pivey, Stagerism Alert: Seurat

- ^ The Topiary Park: A Unique Interpretation of a Painting Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "First Look: NBC's amazing new 'The Office' poster". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015.

- ^ "The Oakland Issue". San Francisco Magazine.

- ^ "Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

Further reading[]

- O'Neill, J, ed. (1991). Georges Seurat, 1859–1891. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- William R. Everdell, The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth Century Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

- "Firey Peril in a Showcase of Modern Art", Life magazine—April 28, 1958 article on the MOMA fire with a picture of the painting being covered by workers.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte. |

- Seurat and the Making of La Grande Jatte

- La Grande Jatte – Inspiration, Analysis and Critical Reception

- About this Artwork, Art Institute of Chicago

- Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, MoMA exhibition catalog

- Georges Seurat, Sunday Afternoon at La Grande Jatte, ColourLex

- Roch, Christine L. "From "Rube Town" to Modern Metropolis:". Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- 1886 paintings

- Dogs in art

- Monkeys in art

- Musical instruments in art

- Paintings by Georges Seurat

- Paintings in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago

- Post-impressionist paintings

- Ships in art