Achlorhydria

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

| Achlorhydria | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypochlorhydria |

| |

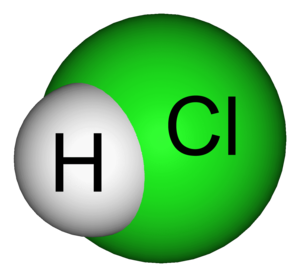

| Hydrogen chloride (major component of gastric acid) | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Internal medicine |

Achlorhydria and hypochlorhydria refer to states where the production of hydrochloric acid in gastric secretions of the stomach and other digestive organs is absent or low, respectively.[1] It is associated with various other medical problems.

Signs and symptoms[]

Irrespective of the cause, achlorhydria can result as known complications of bacterial overgrowth and intestinal metaplasia and symptoms are often consistent with those diseases:

- gastroesophageal reflux disease[2]

- abdominal discomfort

- early satiety

- weight loss

- diarrhea

- constipation

- abdominal bloating

- anemia

- stomach infection

- malabsorption of food

- carcinoma of stomach

Since acidic pH facilitates the absorption of iron, achlorhydric patients often develop iron deficiency anemia. Acidic environment of stomach helps conversion of pepsinogen into pepsin, which is highly important in digesting the protein into smaller components, such as a complex protein into simple peptides and amino acids inside the stomach, which are later absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract.

Bacterial overgrowth and B12 deficiency (pernicious anemia) can cause micronutrient deficiencies that result in various clinical neurological manifestations, including visual changes, paresthesias, ataxia, limb weakness, gait disturbance, memory defects, hallucinations and personality and mood changes.

Risk of particular infections, such as Vibrio vulnificus (commonly from seafood) is increased. Even without bacterial overgrowth, low stomach acid (high pH) can lead to nutritional deficiencies through decreased absorption of basic electrolytes (magnesium, zinc, etc.) and vitamins (including vitamin C, vitamin K, and the B complex of vitamins). Such deficiencies may be involved in the development of a wide range of pathologies, from fairly benign neuromuscular issues to life-threatening diseases.

Causes[]

- The slowing of the body's basal metabolic rate associated with hypothyroidism

- Pernicious anemia where there is antibody production against parietal cells which normally produce gastric acid.[3]

- The use of antacids or drugs that decrease gastric acid production (such as H2-receptor antagonists) or transport (such as proton pump inhibitors).

- A symptom of rare diseases such as mucolipidosis (type IV).

- A symptom of Helicobacter pylori infection which neutralizes and decreases secretion of gastric acid to aid its survival in the stomach.[4]

- A symptom of atrophic gastritis or of stomach cancer.

- Radiation therapy involving the stomach.

- Gastric bypass procedures such as a duodenal switch and RNY, where the largest acid producing parts of the stomach are either removed, or blinded.

- VIPomas (vasoactive intestinal peptides) and somatostatinomas are both islet cell tumors of the pancreas.

- Pellagra, caused by niacin deficiency.

- Chloride, sodium, potassium, zinc and/or iodine deficiency, as these elements are needed to produce adequate levels of stomach acid (HCl).

- Sjögren's syndrome, an autoimmune disorder that destroys many of the body's moisture-producing enzymes

- Ménétrier's disease, characterized by hyperplasia of mucous cells in the stomach also causing excess protein loss, leading to hypoalbuminemia. Presents with abdominal pain and edema

Risk Factors[]

Age

It was found that the incidence of achlorhydria in patients under the age of 60 was around 2.3%, whereas it was 5% in patients over the age of 60.[5] In a person's 30s, the prevalence is about 2.5%, and increases to 12% in a person's 80s.

An absence of hydrochloric acid increases with advancing age. A lack of hydrochloric acid produced by the stomach is one of the most common age-related caused of a harmed digestive system.[6]

Among men and women, 27% suffer from a varying degree of achlorhydria. US researchers found that over 30% of women and men over the age of 60 suffer from having little to no acid secretion in the stomach. Additionally, 40% of postmenopausal women have shown to have no basal gastric acid secretion in the stomach, with 39.8% occurring in females 80 to 89 years old [6]

Autoimmune Disorders

Autoimmune disorders are also linked to advancing age, specifically autoimmune gastritis, which is when the body produces unwelcomed antibodies and causes inflammation of the stomach.[5] Autoimmune disorders are also a cause for small bacterial growth in the bowel and a deficiency of Vitamin B-12. These have also proved to be factors of acid secretion in the stomach.[7]

Hypothyroidism: Thyroid hormones are a factor in the decreasing of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, thus hypothyroidism is associated with a greater risk of developing achlorhydria.[5]

Autoimmune conditions are often managed using various treatments; however, these treatments have no known effect on achlorhydria.[5]

Other[]

Other risk factors include, over the counter acid-blocking medications and antibiotics that may be used to block stomach acid. These medications are often taken by individuals for a longer than recommended period, even for years, despite causing adverse effects on stomach acid secretion.[7]

Stress has also been proven to be linked to symptoms associated with achlorhydria including constant belching, constipation, and abdominal pain.[7]

Diagnosis[]

For practical purposes, gastric pH and endoscopy should be done in someone with suspected achlorhydria. Older testing methods using fluid aspiration through a nasogastric tube can be done, but these procedures can cause significant discomfort and are less efficient ways to obtain a diagnosis.

A complete 24-hour profile of gastric acid secretion is best obtained during an esophageal pH monitoring study.

Achlorhydria may also be documented by measurements of extremely low levels of (PgA) (< 17 µg/L) in blood serum. The diagnosis may be supported by high serum gastrin levels (> 500–1000 pg/mL).[8]

The "Heidelberg test" is an alternative way to measure stomach acid and diagnose hypochlorhydria/achlorhydria.

A check can exclude deficiencies in iron, calcium, prothrombin time, vitamin B-12, vitamin D, and thiamine. Complete blood count with indices and peripheral smears can be examined to exclude anemia. Elevation of serum folate is suggestive of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Bacterial folate can be absorbed into the circulation.

Once achlorhydria is confirmed, a hydrogen breath test can check for bacterial overgrowth.

Treatment[]

Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause of symptoms.

Treatment of gastritis that leads to pernicious anemia consists of parenteral vitamin B-12 injection. Associated immune-mediated conditions (e.g., insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroiditis) should also be treated. However, treatment of these disorders has no known effect in the treatment of achlorhydria.

Achlorhydria associated with Helicobacter pylori infection may respond to H. pylori eradication therapy, although resumption of gastric acid secretion may only be partial and it may not always reverse the condition completely.[9]

Antimicrobial agents, including metronidazole, amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium, ciprofloxacin, and rifaximin, can be used to treat bacterial overgrowth.

Achlorhydria resulting from long-term proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use may be treated by dose reduction or withdrawal of the PPI.

Prognosis[]

Little is known on the prognosis of achlorhydria, although there have been reports of an increased risk of gastric cancer.[10]

A 2007 review article noted that non-Helicobacter bacterial species can be cultured from achlorhydric (pH > 4.0) stomachs, whereas normal stomach pH only permits the growth of Helicobacter species. Bacterial overgrowth may cause false-positive H. pylori test results due to the change in pH from urease activity.[11]

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth is a chronic condition. Retreatment may be necessary once every 1–6 months.[12] Prudent use of antibacterials now calls for an antimicrobial stewardship policy to manage antibiotic resistance.[13]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Kohli, Divyanshoo R., Jennifer Lee, and Timothy R. Koch. "Achlorhydria." Medscape. Ed. B S. Anand. N.p., 29 Apr. 2015. Web. 25 May 2015.

- ^ Kines, Kasia, and Tina Krupczak. "Nutritional Interventions for Gastroesophageal Reflux, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Hypochlorhydria: A Case Report." Integr Med. 2016 Aug 15; 15(4): 49-53.

- ^ "Achlorhydria". Medscape. Jul 15, 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ El-Omar EM, Oien K, El-Nujumi A, et al. (1997). "Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic gastric acid hyposecretion". Gastroenterology. 113 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70075-1. PMID 9207257.

- ^ a b c d Team 2, Health Jade (2019-09-02). "Achlorhydria definition, causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & prognosis". Health Jade. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ a b English, James (2018-11-25). "Gastric Balance: Heartburn Not Always Caused by Excess Acid". Nutrition Review. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ a b c Kines, Kasia; Krupczak, Tina (August 2016). "Nutritional Interventions for Gastroesophageal Reflux, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Hypochlorhydria: A Case Report". Integrative Medicine: A Clinician's Journal. 15 (4): 49–53. ISSN 1546-993X. PMC 4991651. PMID 27574495.

- ^ Divyanshoo Rai Kohli. "Achlorhydria Workup". Medscape. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Iijima, K.; Sekine, H.; Koike, T.; Imatani, A.; Ohara, S.; Shimosegawa, T. (2004). "Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the reversibility of acid secretion in profound hypochlorhydria". Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 19 (11): 1181–1188. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01948.x. PMID 15153171.

- ^ Svendsen JH, Dahl C, Svendsen LB, Christiansen PM (1986). "Gastric cancer risk in achlorhydric patients. A long-term follow-up study". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 21 (1): 16–20. doi:10.3109/00365528609034615. PMID 3952447.

- ^ Brandi G (Aug 2006). "Urease-positive bacteria other than Helicobacter pylori in human gastric juice and mucosa". Am J Gastroenterol. 101 (8): 1756–61. PMID 16780553.

- ^ Divyanshoo Rai Kohli. "Achlorhydria Follow-up". Medscape. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Lee CR, Cho IH, Jeong BC, Lee SH (Sep 12, 2013). "Strategies to minimize antibiotic resistance". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10 (9): 4274–305. doi:10.3390/ijerph10094274. PMC 3799537. PMID 24036486.

External links[]

- Stomach disorders