Akira (manga)

| Akira | |

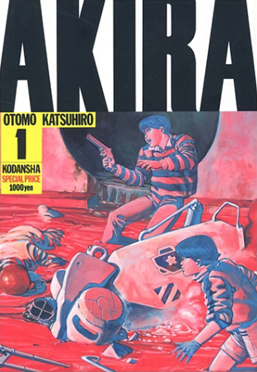

Japanese cover of the first volume of Akira | |

| Genre | |

|---|---|

| Manga | |

| Written by | Katsuhiro Otomo |

| Published by | Kodansha |

| English publisher | |

| Imprint | Young Magazine KC |

| Magazine | Weekly Young Magazine |

| Demographic | Seinen |

| Original run | December 6, 1982 – June 11, 1990 |

| Volumes | 6 |

| Film | |

| |

| Anime television series | |

| Studio | Sunrise[5] |

Akira, often stylized as AKIRA, is a Japanese cyberpunk manga series written and illustrated by Katsuhiro Otomo. It was serialized in Kodansha's seinen manga magazine Weekly Young Magazine from 1982 to 1990, with its chapters collected into six tankōbon volumes.[6] It was published in the United States by Marvel Comics under Epic Comics, becoming one of the first manga ever to be completely translated into English.[7] It is currently published by Kodansha Comics in North America. Considered a watershed title for the medium, [8] the manga is also famous for spawning the seminal 1988 cyberpunk anime film adaptation of the same name and the greater franchise.

Set in a post-apocalyptic and futuristic "Neo-Tokyo", more than two decades after a mysterious explosion destroyed the city, the story centers on teenage biker gang leader Kaneda, militant revolutionary Kei, a trio of espers, and Neo-Tokyo military leader Colonel Shikishima, who attempt to prevent Tetsuo, Kaneda's mentally imbalanced childhood friend, from using his unstable and destructive telekinetic abilities to ravage the city and awaken a mysterious entity with powerful psychic abilities named "Akira". Otomo uses conventions of the cyberpunk genre to detail a saga of political turmoil, social isolation, corruption, and power.[8] Widely regarded as a landmark work in cyberpunk and credited with pioneering the Japanese cyberpunk subgenre, Akira received universal acclaim from readers and critics, with Otomo's artwork, storytelling, characters, and exploration of mature themes and concepts subject to particular praise. The manga also achieved international commercial success, selling millions of copies worldwide.

An animated film adaptation released in 1988 shortened the plot considerably, but retained many of the manga's primary characters and plot elements alongside additional scenes, settings, and motifs. The film was similarly lauded and has served as a significant influence to the anime industry and sci-fi media as a whole.[9] The adaptation also marked Otomo's transition from a career primarily in manga to one almost exclusively in anime.

Akira was instrumental in the surge in popularity of manga outside Japan, especially in the United States, as the release of a colourized edition by Marvel Comics coincided with the release of the film.[10] The manga won several awards, including the Kodansha Manga and Harvey Awards, and is additionally named as an important title in the manga explosion in France.[11]

Plot[]

Volume 1: Tetsuo[]

On December 6, 1982 (1992 in the English version), an apparent nuclear explosion destroys Tokyo and starts World War III. By 2019 (2030 in the English version), a new city called Neo-Tokyo has been built on an artificial island in Tokyo Bay. Although Neo-Tokyo is set to host the XXXII Olympic Games, the city is gripped by anti-government terrorism and gang violence. While exploring the ruins of old Tokyo, Tetsuo Shima, a member of the bōsōzoku gang led by Shōtarō Kaneda, is accidentally injured when his bike crashes after Takashi — a child Esper with wizened features — blocks his path. This incident awakens psychic powers in Tetsuo, attracting the attention of a secret government project directed by JSDF Colonel Shikishima. These increasing powers unhinge Tetsuo's mind, exacerbating his inferiority complex about Kaneda and leading him to assume leadership of the rival Clown Gang through violence.

Meanwhile, Kaneda becomes involved with Kei, a member of a terrorist organization that stage attacks against the government. The terrorists, led by Ryu and opposition parliament leader Nezu, get wind of the Colonel's project and a mysterious figure connected with it known as "Akira". They hope to use this leaked information and try to restrict Kaneda's movements because of his involvement with their activities. However, when Tetsuo and the Clowns begin a violent citywide turf war, Kaneda instigates a counter-attack that unites all of Neo-Tokyo's biker gangs against Tetsuo. While the Clown Gang is easily defeated, Tetsuo's psionic powers make him virtually invincible. Tetsuo kills Yamagata, Kaneda's second-in-command, and astonishingly survives after being shot by Kaneda. The Colonel arrives with the powerful drugs needed to suppress Tetsuo's violent headaches, extending Tetsuo an offer to join the project.

Volume 2: Akira I[]

After their confrontation with the JSDF, Kaneda, Kei, and Tetsuo are taken into military custody and held in a highly secure skyscraper in Neo-Tokyo. Kei soon escapes after becoming possessed as a medium by another Esper, Kiyoko. Kei/Kiyoko briefly does battle with Tetsuo and frees Kaneda. After rapidly healing from his wounds, Tetsuo inquires about Akira, and forces Doctor Onishi, a project scientist, to take him to the other espers: Takashi, Kiyoko, and Masaru. There, a violent confrontation unfolds between Tetsuo, Kaneda, Kei, and the Espers. The Doctor decides to try to let Tetsuo harness Akira — the project's test subject that destroyed Tokyo — despite Tetsuo's disturbed personality. Upon learning that Akira is being stored in a cryogenic chamber beneath Neo-Tokyo's new Olympic Stadium, Tetsuo escapes the skyscraper with the intent of releasing Akira.

The following day, Tetsuo enters the secret military base at the Olympic site, killing many soldiers. The Colonel comes to the base and tries to talk Tetsuo out of his plan; Kaneda and Kei enter the base through the sewers and witness the unfolding situation. Tetsuo breaks open the underground cryogenic chamber and frees Akira, who turns out to be an ordinary-looking little boy. The terror of seeing Akira causes one of the Colonel's men to declare a state of emergency that causes massive panic in Neo-Tokyo. The Colonel himself tries to use SOL, a laser satellite, to kill Tetsuo and Akira, but only succeeds in severing Tetsuo's arm.

Volume 3: Akira II[]

Tetsuo disappears in the subsequent explosion, and Kaneda and Kei come across Akira outside of the base. Vaguely aware of who he is, they take him back into Neo-Tokyo. Both the Colonel's soldiers and the followers of an Esper named Lady Miyako begin scouring Neo-Tokyo in search for him. Kaneda, Kei, and a third terrorist, Chiyoko, attempt to find refuge with Akira on Nezu's yacht. However, Nezu betrays them and kidnaps Akira for his use, attempting to have them killed. They survive the attempt and manage to snatch Akira from Nezu's mansion. The Colonel, desperate to find Akira and fed up with the government's tepid response to the crisis, mounts a coup d'état and puts the city under martial law. The Colonel's men join Lady Miyako's acolytes and Nezu's private army in chasing Kaneda, Kei, Chiyoko, and Akira through the city.

The pursuit ends at a canal, with Kaneda's group surrounded by the Colonel's troops. As Akira is being taken into the Colonel's custody, Nezu attempts to shoot Akira rather than have him be put into government hands; he is immediately fired upon and killed by the Colonel's men. However, Nezu's shot misses Akira and hits Takashi in the head, killing him instantly. The trauma of Takashi's death causes Akira to trigger a second psychic explosion that destroys Neo-Tokyo. Kei, Ryu, Chiyoko, the Colonel, and the other two Espers survive the catastrophe; Kaneda, however, disappears as he is surrounded by the blast. After the city's destruction, Tetsuo reappears and meets Akira.

Volume 4: Kei I[]

Some time later, an American reconnaissance team led by Lieutenant George Yamada covertly arrives in the ruined Neo-Tokyo. Yamada learns that the city has been divided into two factions: the cult of Lady Miyako, which provides food and medicine for the destitute refugees, and the Great Tokyo Empire, a group of zealots led by Tetsuo with Akira as a figurehead, both worshiped as deities for performing "miracles". The Empire constantly harasses Lady Miyako's group and kills any intruders with Tetsuo's psychic shock troops. Kiyoko and Masaru become targets for the Empire's fanatical soldiers: Kei, Chiyoko, the Colonel, and Keisuke, a former member of Kaneda's gang, ally themselves with Lady Miyako to protect them.

Yamada eventually becomes affiliated with Ryu, and updates him on how the world has reacted to the events in Neo-Tokyo; they later learn that an American naval fleet lingers nearby. Tetsuo becomes heavily dependent on government-issued pills to quell his headaches. Seeking answers, he visits Lady Miyako at her temple and is given a comprehensive history of the government project that unleashed Akira. Miyako advises Tetsuo to quit the pills to become more powerful; Tetsuo begins a withdrawal. Meanwhile, Tetsuo's aide, the Captain, stages an unsuccessful Empire assault on Miyako's temple. After the Colonel uses SOL to attack the Empire's army, a mysterious event opens a rift in the sky dumping massive debris from Akira's second explosion, as well as Kaneda.

Volume 5: Kei II[]

Kaneda is reunited with Kei and joins Kaisuke and Joker, the former Clown leader, in planning an assault on the Great Tokyo Empire. Meanwhile, an international team of scientists meets up on an American aircraft carrier to study the recent psychic events in Neo-Tokyo, forming Project Juvenile A. Ryu has a falling out with Yamada after learning that he plans to use biological weapons to assassinate Tetsuo and Akira; Yamada later meets up with his arriving commando team. Akira and Tetsuo hold a rally at the Olympic Stadium to demonstrate their powers to the Empire, which culminates with Tetsuo tearing a massive hole in the Moon's surface and encircling it with a ring of the debris.

Following the rally, Tetsuo's power begins to contort his physical body, causing it to absorb surrounding objects; he later learns that his abuse of his powers has caused them to expand beyond the confines of his body, giving him the ability to transmute inert matter into flesh and integrate it into his physical form. Tetsuo makes a series of visits on board the aircraft carrier to attack the scientists and do battle with American fighter jets. Eventually, Tetsuo takes over the ship and launches a nuclear weapon over the ocean. Kei—accepting the role of a medium controlled by Lady Miyako and the Espers—arrives and battles Tetsuo. Meanwhile, Kaneda, Keisuke, Joker, and their small army of bikers arrive at the Olympic Stadium to begin their all-out assault on the Great Tokyo Empire.

Volume 6: Kaneda[]

As Kaneda and the bikers launch their assault on the stadium, Tetsuo returns from his battle with Kei. As his powers continue to grow, Tetsuo's body begins involuntarily morphing, and his cybernetic arm is destroyed as his original arm regrows. He then faces Yamada's team, but absorbs their biological attacks and temporarily regains control of his powers. Tetsuo kills Yamada and the commandos; he also eludes the Colonel's attempts to kill him by guiding SOL with a laser designator. Kaneda confronts Tetsuo, and the two begin to fight; they are joined by Kei. However, the brawl is interrupted when the Americans try to carpet bomb Neo-Tokyo and destroy the city outright with their laser satellite, FLOYD. Tetsuo flies into space and brings down FLOYD, causing it to crash down upon the aircraft carrier, killing the fleet admiral and one of the scientists.

After the battle, Tetsuo tries to resurrect Kaori, a girl he loved who was killed in the battle. He succeeds to a small degree but is unable to maintain focus. He retreats to Akira's cryogenic chamber beneath the stadium, carrying her body. Kaneda and his friends appear to fight Tetsuo once more, but his powers transform him into a monstrous, amoeba-like mass resembling a fetus, absorbing everything near him. Tetsuo pulls the cryogenic chamber above-ground and drops it onto Lady Miyako's temple. Lady Miyako dies while defying Tetsuo, after guiding Kei into space to fire upon him with SOL. Kei's attack awakens Tetsuo's full powers, triggering a psychic reaction similar to Akira's. With the help of Kiyoko, Masaru, and the spirit of Takashi, Akira can cancel out Tetsuo's explosion with one of his own. They are also able to free Kaneda, who was trapped in Tetsuo's mass, and he witnesses the truth about the Espers' power as they, alongside Akira and Tetsuo, ascend to a higher plane of existence.

The United Nations sends forces to help the surviving parties of Neo-Tokyo. Kaneda and his friends confront them, declaring the city's sovereignty as the Great Tokyo Empire and warning them that Akira still lives in their hearts. Kaneda and Kei meet up with the Colonel and part ways as friends. As Kaneda and Kei ride through Neo-Tokyo with their followers, they are joined by ghostly visions of Tetsuo and Yamagata. They also see the city shedding its ruined façade, returning to its former splendor.

Characters[]

- Kaneda (金田)

- Kaneda (born September 5, 2003),[12] full name Shōtarō Kaneda (金田 正太郎, Kaneda Shōtarō), is the main protagonist of Akira. He is an antiheroic, brash, carefree delinquent and the leader of a motorcycle gang. Kaneda is best friends with Tetsuo, a member who he has known since childhood, but their friendship was ruined after Tetsuo gained and abused his psychic powers. He becomes involved with the terrorist resistance movement and forms an attraction for their member Kei, which eventually develops into a strong romantic bond between the two. During the events of volume 3, Kaneda is surrounded by the explosion caused by Akira and is transported to a place "beyond this world", according to Lady Miyako. Kaneda returns at the end of volume 4, and alongside the Colonel, Joker, Ryu, Keisuke, Miyako, the Espers and Kei, they take down Tetsuo. Kaneda is ranked as #11 on IGN's Top 25 Anime Characters of All Time list.[13]

- Kei (ケイ)

- Kei (born March 8, 2002),[12] real name unknown, is the secondary protagonist of Akira. Strong-willed and sensitive, she is a member of the terrorist resistance movement led by the government mole Nezu. She initially claims to be the sister of fellow resistance fighter Ryu, though it is implied that this is not true. Kei at first views Kaneda with contempt, finding him arrogant, gluttonous and chauvinistic. However, in volume 4, Lady Miyako deduces that she has fallen in love with him, and they become romantically involved following Kaneda's return in volume 5. Kei is a powerful medium who cannot use psychic powers of her own but can channel the powers of others through her body. She is taken in by Lady Miyako and plays a critical role in the final battle.

- Tetsuo (鉄雄)

- Tetsuo (born July 23, 2004),[12] full name Tetsuo Shima (島 鉄雄, Shima Tetsuo), is the main antagonist of Akira. He evolves from Kaneda's best friend and gang member to his nemesis. He is involved in an accident at the very beginning of the story, which causes him to display immense psychic powers. He is soon recruited by the Colonel and became a test subject known as No. 41 (41号, Yonjūichi-gō). It is mentioned that he is Akira's successor; however, Tetsuo's mental instability increases with the manifestation of his powers, which ultimately drives him insane and he ruins his friendship with Kaneda. Later in the story, he becomes Akira's second-in-command, before he begins to lose control of his powers. Eventually, Kei battles Tetsuo, unlocking his full power and triggering another psychic explosion. Akira, watched by his fellow Espers, absorbs Tetsuo's explosion by creating one of his own. With Akira and the espers, he ascends to a higher plane of existence.

- The Colonel (大佐, Taisa)

- The Colonel (born November 15, 1977),[12] last name Shikishima (敷島), is the head of the secret government project conducting research on psychic test subjects (including the Esper children, Tetsuo, and formerly Akira). Although he initially appears to be an antagonist, the Colonel is an honorable and dedicated soldier committed to protecting Neo-Tokyo from any second onslaught of Akira. Later in the story, he provides medical aid to an ill Chiyoko and works with Kei. He is usually referred to by Kaneda as "The Skinhead", due to his distinctive crew cut.

- The Espers

- The Espers, also known as the Numbers (ナンバーズ, Nanbāzu), are three children who are test subjects for the secret project. They are the only survivors of the test, following that of Lady Miyako (No. 19), and given numbers between twenty and thirty. No. 23 was shown in the final chapter to have been amongst those "in whom the power awoke" but "were left with crippling handicaps". At the time of the story, test subjects Nos. 29, 30 and 31 are not mentioned, Nos. 32, 33, 36, 37, 38 and 40 had died from brain injuries during treatment and Nos. 34, 35 and 39, who was in the secret base when Akira destroyed Neo-Tokyo, were subsequently listed as missing (they do not appear in the story). Akira was the only one of this generation with true power, with the others being evaluated as "harmless" (their considerable powers notwithstanding; they did not, however, represent a destructive threat of Akira's magnitude). The three have the bodies of children but chronologically are in their late 30s. Their bodies and faces have wizened with age, but they have not physically grown. They are former acquaintances of Akira and survived the destruction of Tokyo. The Espers include:

- Kiyoko (キヨコ, designated No. 25 (25号, Nijūgo-gō))

- Kiyoko (born 1979)[12] is an Esper who is confined to a bed at all times due to her lack of strength, which is why her companions Takashi and Masaru are protective of her. She can use teleportation, precognition and psychokinesis (as shown when levitating herself and Takashi's corpse when Akira destroys Neo-Tokyo). She predicted the demise of Neo-Tokyo and Tetsuo's involvement with Akira but did not tell the Colonel the full story right away. She is also shown to be a mother figure and leader of the other Espers for decision making.

- Takashi (タカシ, designated No. 26 (26号, Nijūroku-gō))

- Takashi (born 1980)[12] is the first Esper to be introduced when he causes Tetsuo's accident in self-defense. He has the power to use psychokinesis and communicates with his fellow psychics telepathically. Takashi is a quiet, softspoken boy who has conflicting thoughts of the government and the people who had sheltered him and his friends, which was why he escaped the Colonel's facility; however, Takashi is concerned for Kiyoko's safety, and that forces him to stay. Takashi is accidentally killed by Nezu in his attempt to assassinate Akira, and the psychic trauma revolving around it afterward caused Akira to destroy Neo-Tokyo with his immense powers. He is revived along with the rest of the deceased Espers near the end of the series.

- Masaru (マサル, designated No. 27 (27号, Nijūnana-gō))

- Masaru (born 1980)[12] is overweight and confined either to a wheelchair or a special floating chair as a result of developing polio at a young age. He has the power to use psychokinesis and communicates with his fellow psychics telepathically. He is braver than Takashi and is the first to attack Tetsuo when he tries killing Kiyoko. Masaru looks after the well-being of his friends, especially that of Kiyoko who is physically frail.

- Akira (アキラ, designated No. 28 (28号, Nijūhachi-gō))

- Akira is the eponymous character of the series. He has immense psychic powers, although from outward appearances he looks like a small, normal child. He is responsible for the destruction of Tokyo and the beginning of World War III. After the war, he was placed in cryogenics not far from the crater created by him, and the future site of the Neo-Tokyo Olympic Games. Shortly after being awoken by Tetsuo, he destroys Neo-Tokyo during a confrontation between Kaneda and the Colonel's forces. Later in the story, he becomes Emperor of the Great Tokyo Empire. When he first appears, Akira has not aged in the decades he was kept frozen. Akira is essentially an empty shell; his powers have overwritten and destroyed his personality, leaving someone who rarely speaks or reacts, with a constant blank expression on his face. In the end, he is shot by Ryu while psychically synced with the increasingly unstable Tetsuo. It is at this moment he is reunited with his friends and regains his personality.

- Kaisuke (甲斐, Kai)

- Keisuke (born January 8, 2004)[14] is a loyal, high-ranking member of Kaneda's gang. He is known for his unorthodox fashion sense, such as neckties, which he adopts to appear intelligent and sophisticated. He is detained by the army and placed in a reform school following the climax of volume 1, but returns in volume 4. Forming alliances with Kei and Lady Miyako, as well as Joker and Kaneda, he plays an instrumental role in the build-up to Kaneda's showdown with Tetsuo.

- Yamagata (山形)

- Yamagata (born November 9, 2003)[14] is a member of Kaneda's gang who serves as Kaneda's right-hand-man. Known for his aggressive, ready-to-fight behavior, he is killed by Tetsuo's powers in volume 1 after attempting to shoot him when Kaneda, unable to kill Tetsuo, loses his gun.

- Joker (ジョーカー, Jōkā)

- Joker is the leader of the Clowns, a motorcycle gang made up of junkies and drug addicts. Joker plays a small role in the beginning but becomes more prominent much later in the story as an ally of Kaneda and Keisuke. He wears clown face paint and often changes the pattern.

- Nezu (根津)

- Nezu (born December 11, 1964)[14] is an opposition parliament member who is also the leader of the terrorist resistance movement against the government. He seems to be the mentor of Kei and Ryu and purports to be saving the nation from the corrupt and ineffective bureaucrats in power. It soon becomes evident, however, that Nezu is just as corrupt, and all that he seeks to do is to seize power for himself. He later betrays Lady Miyako, as well as various other characters, as he attempts to take control of Akira. After losing Akira, he finds Ryu in a dark corridor with the boy in tow. He attempts to kill Ryu, thinking he is a member of Lady Miyako's group all along. Ryu, however, shoots Nezu. He later tries to shoot Akira before he can be taken into the Colonel's custody. He misses and shoots Takashi in the head, instantly killing him. He is in turn shot and killed by the Colonel's men.

- Ryu (竜, Ryū)

- Ryu (born May 31, 1992),[14] short for Ryusaku (竜作, Ryūsaku), is a comrade of Kei's in the resistance movement. As the story progresses, Ryu abandons his terrorist roots and becomes more heroic, working with Yamada and guiding Kaneda to Akira's chamber where Tetsuo is held up, but battles with alcoholism. In the final volume, Ryu reluctantly shoots and "kills" Akira when he begins to release his power; he is killed by falling elevator debris shortly afterward.

- Chiyoko (チヨコ)

- Chiyoko is a tough, heavyset woman and weapons expert who is involved in the resistance and eventually becomes a key supporting character. She acts as a mother figure (addressed at times as "Aunt") to Kei.

- The Doctor (ドクター, Dokutā)

- The Doctor (born January 28, 1958),[14] last name Onishi (大西, Ōnishi), is the head scientist of the secret psychic research project and also serves as the Colonel's scientific advisor. He belonged to the second generation of scientists overseeing the project after Akira killed the first. It is his curiosity and negligence for anyone's well-being that unlocks and nurtures Tetsuo's destructive power in the first place. When Akira is freed by Tetsuo from his cryogenic lair, the Doctor fails to get inside the shelter and freezes to death.

- Lady Miyako (ミヤコ様, Miyako-sama)

- Lady Miyako is a former test subject known as No. 19. She is shown to possess precognitive and telepathic powers, as well as, in the final altercation with Tetsuo, telekinetic abilities. She is the high priestess of a temple in Neo-Tokyo and a major ally of Kaneda and Kei as the story progresses. Lady Miyako is also an initial ally of Nezu and gives Tetsuo a lecture on his powers. She plays an instrumental role in the final battle with Tetsuo at the cost of her own life, and after her death speaks to Kaneda when he, having previously been absorbed by Tetsuo, is transported to a place "beyond this world".

- Sakaki (サカキ, also 榊)

- Sakaki is an empowered and fond disciple of Lady Miyako and apparent leader of her team of three. Although small and unassuming, she uses her powers to become much faster and stronger than the average person. Tomboyish in appearance, she is sent to battle the Espers, the military, Kaneda, and Nezu to recover Akira. Sakaki only appears in the third volume, in which she is killed by the military. Before her death Lady Miyako utters Sakaki's name, emphasizing their close relationship.

- Mozu (モズ)

- Mozu is a girl, plump in appearance, who is an empowered and fond disciple of Lady Miyako. She later teams with Sakaki and Miki to recover Akira. Mozu only appears in the third volume, in which she is killed by a reluctant Takashi who psychically turns her attack back on her.

- Miki (ミキ)

- Miki is an empowered girl, gaunt in appearance and third fond disciple of Lady Miyako. She only appears in the third volume, in which she is killed by Nezu's henchmen.

- The Great Tokyo Empire (大東京帝国, Dai Tōkyō Teikoku)

- The Great Tokyo Empire is a small army which rises amid the ruins of Neo-Tokyo after its destruction at the hands of Akira, made up of crazed zealots who worship Akira as an Emperor for the "miracles" he performs, though the power lies squarely with his so-called Prime Minister, Tetsuo. Disorganized and unruly, the army rejects outside aid and wars with Lady Miyako's followers. Tetsuo secretly drugs the rations distributed to its members. At the end of the story, Kaneda and friends take the Empire's name and declare Neo-Tokyo a sovereign nation, expelling the American and United Nations forces that land in the city.

- Kaori (カオリ)

- Kaori is a young girl who appears late in the story and is recruited as one of Tetsuo's sex slaves. She is later becoming an object of his sincere affections. Kaori also serves as Akira's babysitter. She is later shot in the back by the Captain. Tetsuo attempts to resurrect her but fails.

- The Captain (隊長, Taichō)

- The Captain is an opportunist, posing as a fanatical devotee of Tetsuo who serves him as his aide-de-camp late in the story but secretly desires control of the Great Tokyo Empire. Despite his scheming, the Captain shows some compassion, begging Tetsuo not to kill or harm the young women he has procured for him as they still have families. During the confrontation between Tetsuo and the U.S. Marines, he is caught in the crossfire and is killed by the bacterial gas Yamada uses.

- The Birdman (鳥男, Tori Otoko)

- The Birdman is one of Tetsuo's elite psychic shock-troops. He wears a blindfold and is frequently standing atop ruined buildings and rafters, observing and reporting on the goings-on within the Empire's turf, and essentially acting as a security system. It is implied that his psychic powers allow him to sense sights and sounds from a great distance, further embodied by the all-seeing eye drawn on his forehead. He also possesses telepathic (his announcements are observed by a Marine to be "like a voice in my head") and telekinetic abilities. Birdman dies when Yamada knocks him from his perch, causing him to fall to his death.

- The Eggplant man (ホーズキ男, Hōzuki Otoko)

- The Eggplant man is a member of Tetsuo's shock troops. He is described as a fat, short man with glasses who encounters Yamada and the Marines at Olympic Stadium. He was friends with Birdman, and attempts to telekinetically crush a Marine's heart before being executed by Yamada.

- Lieutenant Yamada (山田中尉, Yamada-chūi)

- Lieutenant Yamada, full name George Yamada (ジョージ 山田, Jōji Yamada), is a Japanese-American soldier who is sent on a mission to assassinate Akira and Tetsuo in the latter half of the story after Akira has leveled Neo-Tokyo. Yamada plans to kill the two powerful psychics with darts containing a biological poison. He is later joined by a team of U.S. Marines to carry out the mission at the Olympic Stadium after it becomes the headquarters for Akira and Tetsuo's Great Tokyo Empire. However, the biochemical weapons fail to harm Tetsuo, instead of giving him temporary control of his expanding powers again, who proceeds to kill Yamada.

- Juvenile A (ジュヴィナイルA, Juvinairu Ē)

- Juvenile A is an international team of scientists who are appointed to investigate psychic events in Neo-Tokyo in the latter half of the story. Its members include Dr. Dubrovsky (ドブロフスキー博士, Doburofusukī-hakase), Dr. Simmons (シモンズ博士, Shimonzu-hakase), Dr. Jorris (ジョリス博士, Jorisu-hakase), Dr. Hock (ホック博士, Hokku-hakase), Professor Bernardi (ベルナルディ教授, Berunarudi-kyōju), and lama Karma Tangi (カルマ・タンギ, Karuma Tangi).

Production[]

Katsuhiro Otomo had previously created Fireball (1979), an unfinished series in which he disregarded accepted manga art styles and which established his interest in science fiction as a setting. Fireball anticipated a number of plot elements of Akira, with its story of young freedom fighters trying to rescue one of the group's older brother who was being used by the government in psychic experiments, with the older brother eventually unleashing a destructive "fireball" of energy (the story may have drawn inspiration from the Alfred Bester's 1953 novel The Demolished Man).[15] The setting was again used the following year in Domu, which was awarded the Science Fiction Grand Prix and became a bestseller. Otomo then began work on his most ambitious work to date, Akira. While Akira came to be viewed as part of the emerging cyberpunk genre, it predates the seminal cyberpunk novel Neuromancer (1984), which was released two years after Akira began serialization in 1982 and was not translated into Japanese until 1985.[16]

For its overseas release, to reach a larger audience, Otomo decided to color the manga and to carefully flip the pages so that they would be read from left to right, like American comics, instead of the traditional black and white artwork and right to left reading. Some of the artwork was redrawn by Otomo and his assistants to flip it, while the coloring was done by Steve Oliff at his company, Olyoptics.[17] Akira was the first comic in the world to be colored digitally, using computers. Its release in color led to the widespread adoption of computer coloring in comics.[18][19] Coloring lasted from 1988 to 1994, being delayed by Otomo's work on Steamboy, and Oliff's work in Akira earned him an Eisner Award in 1992.[17]

Otomo cited the influence of works such as the movie Star Wars,[20] the comics of Moebius,[21][22] the manga Tetsujin 28-go,[15][23] the science fiction works of Seishi Yokomizo which dealt with "new breeds" of humanity,[16][24] and Sogo Ishii's punk films Panic High School (1978) and Crazy Thunder Road (1980) which portrayed the rebellion, anarchy and biker gangs associated with Japanese punk rock subculture.[25] Famed manga artist and film director Satoshi Kon acted as an uncredited assistant artist for the series.[26]

Otomo and his design office, Pencil Studio, originally tried futuristic typefaces such as Checkmate and Earth for the font used in the title logo, but eventually Otomo used condensed sans-serif capitals. The font was once told to be Impact, but did not match the actual design. It was speculated to be hand-drawn based on Schmalfette Grotesk.[27] Other fonts have also been used for the logo, such as Broadway in issue 36, ITC Busorama in issues 37–48, Futura in issues 72 to 120.

Themes[]

Akira, like some of Otomo's other works (such as Domu), revolves around the basic idea of individuals with superhuman powers, especially psychokinetic abilities. However, these are not central to the story, which instead concerns itself with character, societal pressures and political machination.[7] Motifs common in the manga include youth alienation, government corruption and inefficiency, and a military grounded in old-fashioned Japanese honor, displeased with the compromises of modern society.

Jenny Kwok Wah Lau writes in Multiple Modernities that Akira is a "direct outgrowth of war and postwar experiences." She argues that Otomo grounds the work in recent Japanese history and culture, using the atomic bombing of Japan during World War II, alongside the economic resurgence and issues relating to overcrowding as inspirations and underlying issues. Thematically, the work centers on the nature of youth to rebel against authority, control methods, community building and the transformation experienced in adolescent passage. The latter is best represented in the work by the morphing experienced by characters.[28]

Susan J. Napier identified this morphing and metamorphosis as a factor that marks the work as postmodern: "a genre which suggests that identity is in constant fluctuation." She also sees the work as an attack on the Japanese establishment, arguing that Otomo satirizes aspects of Japanese culture: in particular, schooling and the rush for new technology. Akira's central image of characters aimlessly roaming the streets on motorbikes is seen to represent the futility of the quest for self-knowledge. The work also focuses on loss, with all characters in some form orphaned and having no sense of history. The landscapes depicted are ruinous, with old Tokyo represented only by a dark crater. The nihilistic nature of the work is felt by Napier to tie into a wider theme of pessimism present in Japanese fantasy literature of the 1980s.[29]

Release[]

Akira launched in 1982, serialized in Japan's Young Magazine, and concluded in 1990, two years after the film adaptation of the same name was released. The work, totaling more than 2,000 pages, was collected and released in six tankōbon volumes by Kodansha.[7] Concurrently with working on the series, Otomo agreed to an anime adaptation of the work, provided he retained creative control. This insistence was based on his experiences working on Harmagedon. The film was released theatrically in Japan in 1988, and followed by limited theatrical releases in various Western territories from 1989 to 1991.[23][30]

In 1988, the manga was published in the United States by Epic Comics, an imprint of Marvel Comics. This colorized version ended its 38-issue run in 1995. The coloring was by Steve Oliff, hand-picked for the role by Otomo. Oliff persuaded Marvel to use computer coloring, and Akira became the first ongoing comic book to feature computer coloring. The coloring was more subtle than that seen before and far beyond the capabilities of Japanese technology of the time. It played an important part in Akira's success in Western markets, and revolutionized the way comics were colorized.[31] Delays in the publication were caused by Otomo's retouching of artwork for the Japanese collections. It was these works which formed the basis for translation, rather than the initial serialization. The Epic version suffered significant delays toward the end of the serial, requiring several years to publish the final 8 issues. Marvel planned to collect the colorized versions as a 13-volume paperback series, and teamed with Graphitti Designs to release six limited-edition hardcover volumes; however, the collected editions ceased in 1993, so the final 3 paperbacks and planned sixth hardcover volume was never published. A partially colorized version was serialized in British comic/magazine Manga Mania in the early to mid-'90s.

A new edition of Akira was later published in paperback from 2000 to 2002 by Dark Horse Comics, and in the UK by Titan Books, this time in its original 6-volume black-and-white form with a revised translation, although Otomo's painted color pages were used minimally at the start of each book as in the original manga.[4][32] The English-language rights to Akira are currently held by Kodansha Comics, who re-released the manga from 2009 to 2011 through Random House. Kodansha's version is largely identical to the Dark Horse version.[33][34] In honor of the 35th anniversary of the manga, Kodansha released a box set in late October 2017, containing hardcover editions of all six volumes, as well as the Akira Club art book, and an exclusive patch featuring the iconic pill design. This release was presented in the original right-to-left format, with unaltered original art and Japanese sound effects with endnote translations.[35][36][37]

The serial nature of the work influenced the storyline structure, allowing for numerous sub-plots, a large cast, and an extended middle sequence. This allowed for a focus on destructive imagery and afforded Otomo the chance to portray a strong sense of movement.[9] He also established a well-realized science fiction setting, and his art evoked a strong sense of emotion within both character and reader.[8] The work has no consistent main character, but Kaneda and Tetsuo are featured the most prominently throughout.[9]

| No. | Title | Original release date | North American release date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tetsuo (鉄雄) | September 14, 1984[38] 978-4-06-103711-3 | December 13, 2000 978-1-56971-498-0 (Dark Horse)[4] October 13, 2009 ISBN 978-1-935429-00-5 (Kodansha)[33] |

| Chapters 1–18, originally serialized from December 1982 to September 1983.[39] | |||

| 2 | Akira I (アキラ I) | August 27, 1985[40] 978-4-06-103712-0 | March 28, 2001 978-1-56971-499-7 (Dark Horse)[41] June 22, 2010 ISBN 978-1-935429-02-9 (Kodansha)[42] |

| Chapters 19–33, originally serialized from September 1983 to May 1984.[43] | |||

| 3 | Akira II (アキラ II) | August 21, 1986[44] 978-4-06-103713-7 | June 27, 2001 978-1-56971-525-3 (Dark Horse)[45] July 13, 2010 ISBN 978-1-935429-04-3 (Kodansha)[46] |

| Chapters 34–48, originally serialized from May 1984 to January 1985.[47] | |||

| 4 | Kei I (ケイ I) | July 1, 1987[48] 978-4-06-103714-4 | September 19, 2001 978-1-56971-526-0 (Dark Horse)[49] November 30, 2010 ISBN 978-1-935429-06-7 (Kodansha)[50] |

| Chapters 49–71, originally serialized from March 1985 to April 1986.[51] | |||

| 5 | Kei II (ケイ II) | November 26, 1990[52] 978-4-06-313166-6 | December 19, 2001 978-1-56971-527-7 (Dark Horse)[53] March 01, 2011 ISBN 978-1-935429-07-4 (Kodansha)[54] |

| Chapters 72–96, originally serialized from May 1986 to April 1989[55] (the series took an extended break after Chapter 87, published on April 1987, allowing Otomo to work on the Movie adaptation). | |||

| 6 | Kaneda (金田) | March 15, 1993[56] 978-4-06-319339-8 | March 27, 2002 978-1-56971-528-4 (Dark Horse)[32] April 12, 2011 ISBN 978-1-935429-08-1 (Kodansha)[34] |

| Chapters 97–120, originally serialized from May 1989 to June 1990.[57] | |||

Reception[]

The first tankōbon volume, which was released on September 14, 1984, significantly exceeded sales expectations, with its print run increasing from an initial 30,000 copies up to nearly 300,000 copies within two weeks, becoming the number-one best-seller in Japan before eventually selling about 500,000 copies. By 1988, Akira had sold approximately 2 million copies in Japan, from four volumes averaging about 500,000 copies each.[58] The manga was published in the United States in 1988, followed by France, Spain and Italy by 1991, and then Germany, Sweden, South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia and Brazil. It was reported by Critique international that by 2000 Akira had sold 7 million copies worldwide, including 2 million in Japan and 5 million overseas.[59] As of 2005, Akira has been published in more than a dozen languages worldwide.[60] In 2020, the first volume of Akira became publisher Kodansha's first manga to receive a 100th printing.[61] At a price of ¥1,000 in Japan[38] and $24.95 overseas,[4] the manga tankōbon volumes grossed estimated revenues of ¥2 billion ($16 million)[62] in Japan and $125 million overseas, for an estimated total of $141 million grossed worldwide.

During its run, the seinen manga magazine where it was first serialized, Weekly Young Magazine, experienced an increase in its weekly circulation, from 1 million in 1986 to 1.5 million in 1990.[63] At an average manga magazine price of ¥180 at the time,[64] the 120 issues serializing Akira sold an estimated total of 120–180 million copies and grossed an estimated ¥22–32 billion ($170–250 million).[62]

Akira has won much recognition in the industry, including the 1984 Kodansha Manga Award for Best General Manga.[65] Fans in the United Kingdom voted it Favourite Comic at the 1990 Eagle Awards.[66] It won a Harvey Award for Best American Edition of Foreign Material in 1993,[67] and was nominated for a Harvey for Best Graphic Album of Previously Published Work in 2002. In 2002, Akira won the Eisner Awards for Best U.S. Edition of Foreign Material and Best Archival Collection.[68] The 35th anniversary edition won Best Archival Collection again at the 2018 Eisner Awards, in addition to Best Publication Design.[69] In her book The Fantastic in Japanese Literature, Susan Napier described the work as a "no holds barred enjoyment of fluidity and chaos".[70] The work is credited as having introduced both manga and anime to Western audiences.[23] The translation of the work into French in 1991 by Glénat "opened the floodgates to the Japanese invasion."[71] The imagery in Akira, together with that of Blade Runner, formed the blueprint for similar Japanese works of a dystopian nature of the late 1990s. Examples include Ghost in the Shell and Armitage III.[30] Akira cemented Otomo's reputation and the success of the animated feature allowed him to concentrate on film rather than the manga form in which his career began.[7]

Related media[]

While most of the character designs and basic settings were directly adapted from the original manga, the restructured plot of the movie differs considerably from the print version, changing much of the second half of the series. The film Akira is regarded by many critics as a landmark anime film: one that influenced much of the art in the anime world that followed its release.[23][72]

In 2003, Tokyopop published a "reverse adaption" in the form of an Akira "cine-manga." The format consists of animation cels from the film version cut up and arranged with word balloons in order to resemble comic book panels.[citation needed]

A graphic adventure game based on the animated movie adaptation was released in 1988 by Taito for the Famicom console. The video game version has the player in the role of Kaneda, with the storyline starting with Kaneda and his motorcycle gang in police custody. In 1994, a British-made action game was released for the Amiga CD32 and it's considered one of the console's worst games.[73][74] In 2002 Bandai released a pinball simulation, Akira Psycho Ball, for the PlayStation 2.

In June 1995, Kodansha released Akira Club, a compilation of various materials related to the production of the series. These include test designs of the paperback volume covers, title pages as they appeared in Young Magazine, and images of various related merchandise. Otomo also shares his commentaries in each page. Dark Horse collaborated with Kodansha to release an English-translated version of the book in 2007.

Since 2002, Warner Bros. had acquired rights to create an American live action film of Akira.[75] Since the initial announcement, a number of directors, producers and writers have been reported to be attached to the film, starting with Stephen Norrington (writer/director) and Jon Peters (producer).[75][76] By 2017, it was announced Taika Waititi would officially serve as the director of the live-action adaptation, from a screenplay he co-wrote with Michael Golamco.[77] Warner Bros. planned to distribute the film on May 21, 2021, but after Waititi was officially confirmed to both direct and write Thor: Love and Thunder, the film was put on hold and taken off the release slot.[78][79][80]

On July 4, 2019, Bandai Namco Entertainment announced a 4K remaster of the original film set to release on April 24, 2020, as well as a television series to be made by Sunrise.[81][82]

Legacy[]

- It is considered a landmark work in the cyberpunk genre, credited with spawning the Japanese cyberpunk subgenre. It inspired a wave of Japanese cyberpunk-infused manga and anime works, including Ghost in the Shell, Battle Angel Alita, Cowboy Bebop, and Serial Experiments Lain.[83]

- Manga author Tetsuo Hara cited the manga Akira as an influence on the dystopian post-apocalyptic setting of Fist of the North Star (1983 debut).[84]

- In various interviews with the U.S. edition of Shonen Jump, Naruto creator Masashi Kishimoto has cited the Akira manga and anime as major influences, particularly as the basis of his own manga career.[85]

- Tooru Fujisawa, creator of manga and anime series Great Teacher Onizuka (GTO), cited Akira as one of his greatest inspirations and said it changed the way he wrote.[86]

- Acclaimed anime director Satoshi Kon was credited for some of the artwork in the Marvel editions of Akira.

- Josh Trank, the director of the film Chronicle, cited Akira as an influence.[87]

- Sean Lennon has expressed being a fan of the story, since he was a child living in Japan.[88]

- The Akira Class starship from the Star Trek franchise, and first introduced in the 1996 feature film Star Trek First Contact, was named after the anime by its designer Alex Jaeger, of Industrial Light & Magic.[89]

- In The King of Fighters 2002, Kusanagi and K9999 have an Akira-esque intro before they fight, since Kusanagi has the same voice as Kaneda and K9999 has the same voice as Tetsuo.

- Kanye West has a tribute to the anime film in his "Stronger" video.[90]

- M83 has created a three-part tribute to Akira (and other influences) with their videos for Midnight City, Reunion[91] and Wait.

- A fan-made web comic parody of the manga created by Ryan Humphrey, Bartkira, is a panel-for-panel retelling of all six volumes of the manga illustrated by numerous artists contributing several pages each, with Otomo's characters being portrayed by members of the cast of The Simpsons: for example, Kaneda is represented by Bart Simpson, Milhouse Van Houten replaces Tetsuo, and Kei and Colonel Shikishima are portrayed by Laura Powers and Principal Skinner respectively.[92]

- Rapper Lupe Fiasco's album Tetsuo & Youth was loosely inspired by the Akira character Tetsuo Shima.[93]

- In the 1992 Neo-Geo game Last Resort, the city depicted in the first two stages of the game is very similar to that of Neo Tokyo from the anime film.

- In the 1998 film Dark City, one of the last scenes, in which buildings "restore" themselves, is similar to the last panel of the Akira manga. The writer-director Alex Proyas called the end battle a "homage to Otomo's Akira".[94]

- In Half-Life, aspects of the level design were influenced directly by scenes from the manga. For example, the diagonal elevator leading down to the sewer canals as well as the design of the canals themselves are taken from scenes in the manga. This was confirmed by Brett Johnson, the Valve employee who designed the levels.[95][96] The Half-Life 2 mod NeoTokyo was also inspired by Akira.[97]

References[]

- ^ "Kodansha Comics Gift Guide Part 3: Classics Crusaders". Kodansha Comics. December 9, 2016. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Campbell, Scott (November 13, 2009). "Akira Vol. 1". activeAnime. Archived from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ McCarthy, Helen (2014). A Brief History of Manga: The Essential Pocket. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-78157-130-9.

Combining science fiction and political thriller, action adventure, and meditation on the state of the world, Akira is a truly remarkable work.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Akira Vol.1 TPB". Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ Robertson, Adi. "Akira is getting a 4K remaster and a new anime series". The Verge. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Gresh, Lois H.; Robert Weinberg (2005). The Science of Anime. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 168. ISBN 1-56025-768-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Brooks, Brad; Tim Pilcher (2005). The Essential Guide to World Comics. London: Collins & Brown. p. 103. ISBN 1-84340-300-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Amano, Masanao; Julius Wiedemann (2004). Manga Design. Taschen. p. 138. ISBN 3-8228-2591-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Martinez, Dolores P. (1998). The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63729-5.

- ^ Jozuka, Emiko (2019-07-29). "How anime shaped Japan's global identity". CNN Style. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ "Pourquoi il faut (re)lire le manga Akira". www.cnews.fr (in French). Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Akira Production Report (DVD). Madman Entertainment. 13 November 2001.

- ^ "Top 25 Anime Characters of All Time". IGN. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Characters and Espers". akirakanada.tripod.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clements, Jonathan (2010). Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. A-Net Digital LLC. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-9845937-4-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gravett, Paul (2004). Manga: 60 Years of Japanese Comics. Laurence King Publishing. p. 155. ISBN 1-85669-391-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Interview: Akira in Color with Steve Oliff". Anime News Network.

- ^ Khoury, George (July 9, 2007). Image Comics: The Road to Independence. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781893905719 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gravett, Paul. Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics (Laurence King Publishing, 2004).

- ^ Schilling, Mark (1997). The Encyclopedia of Japanese Pop Culture. Weatherhill. p. 174. ISBN 0-8348-0380-1.

- ^ Lee, Andrew (17 May 2012), Otomo's genga will make you remember, The Japan Times, retrieved 28 August 2013

- ^ Akira's Katsuhiro Otomo Remembers French Artist Moebius, Anime News Network, 9 April 2012, retrieved 28 August 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sabin, Roger (1996). Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels: a History of Comic Art. Phaidon. pp. 230–1. ISBN 0-7148-3993-0.

- ^ Matthews, Robert (1989). Japanese Science Fiction: A View of a Changing Society. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0-415-01031-4.

- ^ Player, Mark (13 May 2011). "Post-Human Nightmares – The World of Japanese Cyberpunk Cinema". Midnight Eye. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Osmond, Andrew (2009). Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist. Stonebridge Press, p. 15. ISBN 978-1933330747

- ^ Schmerber, Quentin (August 19, 2017). "Akira by Katsuhiro Otomo". Fonts in Use.

- ^ Kwok Wah Lau, Jenny (2003). Multiple Modernities. Temple University Press. pp. 189–90. ISBN 1-56639-986-6.

- ^ Jolliffe Napier, Susan (1996). The Fantastic in Modern Japanese Literature. Routledge. pp. 214–8. ISBN 0-415-12458-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 7. ISBN 1-55652-591-5.

- ^ Kôsei, Ono (Winter 1996). "Manga Publishing: Trends in the United States". Japanese Book News. The Japan Foundation. 1 (16): 6–7. ISSN 0918-9580.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Akira Vol.6 TPB". Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Akira Volume 1". Random House. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Akira Volume 6". Random House. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ "Emerald City Comicon Announcement 1 Akira: The... – KODANSHA COMICS". KODANSHA COMICS. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- ^ Barder, Ollie. "Kodansha To Celebrate 35th Anniversary Of 'Akira' Manga With Ultimate Boxset". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- ^ "Akira's $200 35th Anniversary Box Set From Kodansha Gets A Release Date". Bleeding Cool Comic Book, Movie, TV News. 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "AKIRA (1)". Kodansha. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "AKIRA 1". Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- ^ "AKIRA (2)". Kodansha. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Akira Vol.2 TPB". Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ "Akira Volume 2". Random House. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ "AKIRA 2". Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- ^ "AKIRA (3)". Kodansha. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Akira Vol.3 TPB". Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ "Akira Volume 3". Random House. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ "AKIRA 3". Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- ^ "AKIRA (4)". Kodansha. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Akira Vol.4 TPB". Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ "Akira Volume 4". Random House. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ "AKIRA 4". Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- ^ "AKIRA (5)". Kodansha. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Akira Vol.5 TPB". Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ "Akira Volume 5". Random House. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ "AKIRA 5". Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- ^ "AKIRA (6)". Kodansha. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "AKIRA 6". Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- ^ MANGA: Akira Chapter 01. Epic Comics. 1988. p. 61.

- ^ Bouissou, Jean-Marie (2000). "Manga goes global". Critique Internationale. 7 (1): 1–36 (22). doi:10.3406/criti.2000.1577.

- ^ Forbes, Jake (March 17, 2005). "He's the Kubrick of anime". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Rafael Antonio Pineda. "Akira Volume 1 Is 1st Kodansha Manga to Get 100th Printing". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average) - Japan". World Bank. 1988. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "コミック誌の部数水準". Yahoo! Japan. Archived from the original on March 6, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ "An Analysis of Weekly Manga Magazines Price for the Past 30 Years". ComiPress. 2007-04-06.

- ^ Joel Hahn. "Kodansha Manga Awards". Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on 2007-08-16. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ^ Egan Loo. "UK Fans Give Eagle Award to Death Note Manga". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ^ 1993 Harvey Awards, Harvey Award, archived from the original on 15 March 2016, retrieved 1 November 2013

- ^ "2002 EISNER AWARD WINNERS". ICv2. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ^ Crystalyn Hodgkins. "Gengoroh Tagame's My Brother's Husband Manga Wins Eisner Award". Anime News Network. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ^ Bush, Laurence C. (2001). Asian Horror Encyclopedia. Writers Club Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-595-20181-4.

- ^ Brooks, Brad; Tim Pilcher (2005). The Essential Guide to World Comics. London: Collins & Brown. p. 172. ISBN 1-84340-300-5.

- ^ Akira – Movie Reviews, Trailers, Pictures – Rotten Tomatoes Archived 2009-03-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Akira (Amiga) – Hardcore Gaming 101". Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ "Akira - Amiga Game / Games - Download ADF, Music, Cheat - Lemon Amiga". www.lemonamiga.com. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Linder, Brian et al. movies.ign.com Akira (Live Action)", IGN, April 12, 2002. Retrieved October 24, 2006.

- ^ Brice, Jason. "Western Adaption Of Akira Planned". Silverbulletcomicbooks.com. Archived from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Busch, Anita; Flemming, Mike (19 September 2017). "'Akira' Back? 'Thor: Ragnarok' Helmer Taika Waititi In Talks". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (May 24, 2019). "Taika Waititi's 'Akira' Sets 2021 Release Date". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Taika Waititi to Direct 'Thor 4' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (2019-12-11). "Warner Bros Sets Release Dates For 'The Matrix' Sequel, 'The Flash' & More; 'Akira' Off Schedule". Deadline. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ Lawler, Richard. "4K 'Akira' Blu-ray arrives next year before the series continues". Engadget. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Loo, Egan. "Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira Gets New Anime Project & 4K Remaster of 1988 Anime Film". Anime News Network. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ "What is cyberpunk?". Polygon. August 30, 2018.

- ^ Valdez, Nick (December 11, 2017). "'Fist of the North Star' Creator Reveals Inspiration For The Series". ComicBook.com. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Santilli, Morgana. "The untold truth of Naruto". Looper.com. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Fobian, Peter (January 15, 2016). "Monthly Mangaka Spotlight 7: Tohru Fujisawa". Crunchyroll. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Chronicle captures every teen's fantasy of fighting back, say film's creators". Io9.com. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Ohanesian, Liz (2012-03-02). "Sean Lennon Brings Akira and Other Favorites to Los Angeles Animation Festival – Los Angeles – Arts – Public Spectacle". Blogs.laweekly.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Britt, Ryan. "15 Cool Stories of How 'Star Trek' Ships Got Their Names". Inverse. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ "Kanye West says his "biggest creative inspiration" is Akira". The FADER. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ M83. "M83 'Midnight City' Official video". 2011 M83 Recording Inc. Under exclusive license to Mute for North America and to Naïve for the rest of the world. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ Humphrey, Ryan. "Bartkira.com". Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Lupe Fiasco's 'Tetsuo & Youth' Avoiding Politics". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Proyas, Alex. "Dark City DC: Original Ending !?". Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-29.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Mystery Clock Forum. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ "Half-Life – Akira References". YouTube. August 26, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "Half-Life tiene varias referencias a Akira". MeriStation (in Spanish). Diario AS. August 29, 2018.

- ^ "The most impressive PC mods ever made". TechRadar. June 14, 2018.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Akira (manga). |

- Akira (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Manga series

- 1982 manga

- Akira (franchise)

- Comics set in the 2010s

- Comics set in the 21st century

- Cyberpunk anime and manga

- Dark Horse Comics titles

- Epic Comics titles

- Fiction books about psychic powers

- Fiction books about telepathy

- Japan Self-Defense Forces in fiction

- Katsuhiro Otomo

- Kodansha manga

- Manga adapted into films

- Political thriller anime and manga

- Post-apocalyptic anime and manga

- Prosthetics in fiction

- Revenge in anime and manga

- Science fiction anime and manga

- Seinen manga

- Winner of Kodansha Manga Award (General)

- Harvey Award winners

- Eisner Award winners