Amateur radio in India

Amateur radio or ham radio is practised by more than 22,000 licensed users in India.[1] The first amateur radio operator was licensed in 1921, and by the mid-1930s, there were around 20 amateur radio operators in India. Amateur radio operators played an important part in the Indian independence movement with the establishment of illegal pro-independence radio stations in the 1940s. The three decades after India's independence saw only slow growth in the numbers of operators until the then Prime Minister of India and amateur radio operator, Rajiv Gandhi (VU2RG), waived the import duty on wireless equipment in 1984. Since then, numbers have picked up, and as of 2007, there were more than 16,000 operators in the country. Amateur radio operators have played a vital role during disasters and national emergencies such as earthquakes, tsunamis, cyclones, floods, and bomb blasts, by providing voluntary emergency communications in the affected areas.

The Wireless and Planning and Coordination Wing (WPC)—a division of the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology—regulates amateur radio in India. The WPC assigns call signs, issues amateur radio licences, conducts exams, allots frequency spectrum, and monitors the radio waves. Popular amateur radio events include daily ham nets, the annual Hamfest India, and regular DX contests.

History[]

The first amateur radio operator in India was Amarendra Chandra Gooptu (callsign 2JK), licensed in 1921.[5][6] Later that year, Mukul Bose (2HQ) became the second ham operator, thereby introducing the first two-way ham radio communication in the country.[5] By 1923, there were twenty British hams operating in India. In 1929, the call sign prefix VU came into effect in India,[citation needed] replacing three-letter call signs. The first short-wave entertainment and public broadcasting station, "VU6AH", was set up in 1935 by E P Metcalfe, vice-chancellor of Mysore University.[5][6] However, there were fewer than fifty licence holders in the mid-1930s, most of them British officers in the Indian army.[citation needed]

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the British cancelled the issue of new licences.[7] All amateur radio operators were sent written orders to surrender their transmitting equipment to the police, both for possible use in the war effort and to prevent the clandestine use of the stations by Axis collaborators and spies. With the gaining momentum of the Indian independence movement, ham operator Nariman Abarbad Printer (VU2FU) set up the Azad Hind Radio to broadcast Gandhian protest music and uncensored news; he was immediately arrested and his equipment seized. In August 1942, after Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement, the British began clamping down on the activities of Indian independence activists and censoring the media. To circumvent media restrictions, Indian National Congress activists, led by Usha Mehta, contacted Mumbai-based amateur radio operators, "Bob" Tanna (VU2LK) and Nariman Printer to help broadcast messages to grass-roots party workers across the country.[citation needed] The radio service was called the "Congress Radio", and began broadcasting from 2 September 1942 on 7.12 MHz. The station could be received as far as Japanese-occupied Myanmar. By November 1942, Tanna was betrayed by an unknown radio officer and was forced to shut down the station.[7]

Temporary amateur radio licences were issued from 1946, after the end of World War II. By 1948, there were 50 amateur radio operators in India, although only a dozen were active.[5] Following India's independence in 1947, the first amateur radio organization, the Amateur Radio Club of India was inaugurated on 15 May 1948 at the School of Signals at Mhow in Madhya Pradesh.[5] The club headquarters was later moved to New Delhi, where it was renamed the Amateur Radio Society of India (ARSI) on 15 May 1954.[5] As India's oldest amateur radio organization,[citation needed] ARSI became its representative at the International Amateur Radio Union.[8]

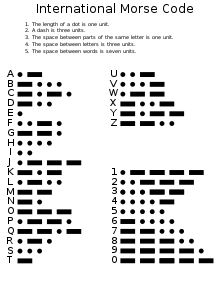

Partly due to low awareness among the general population and prohibitive equipment costs, the number of licensed amateur radio operators did not increase significantly over the next two decades, numbering fewer than a thousand by 1970.[9] CW (Morse code) and AM were the predominant modes at that time. The electronic equipment was mostly valve-based, obtained from Indian army surpluses.[9] During the mid-1960s, the modes of operation saw a change from Amplitude Modulation to Single Side Band (SSB) as the preferred communication mode. By 1980, the number of amateur radio operators had risen to 1,500. In 1984, then Indian Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, waived the import duty for wireless equipment. After this, the number of operators rose steadily, and by 2000 there were 10,000 licensed ham operators.[9] As of 2007, there are more than 17,000 licensed users in India.[1]

Amateur radio operators have played a significant part in disaster management and emergencies. In 1991, during the Gulf War, a lone Indian ham operator in Kuwait, provided the only means of communication between stranded Indian nationals in that country and their relatives in India.[10] Amateur radio operators have also played a helpful part in disaster management. Shortly after the 1993 Latur and 2001 Gujarat earthquakes,[citation needed] the central government rushed teams of ham radio operators to the epicentre to provide vital communication links. In December 2004, a group of amateur radio operators on DX-pedition on the Andaman Islands witnessed the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. With communication lines between the islands severed, the group provided the only way of relaying live updates and messages to stations across the world.[3]

In 2005, India became one of few countries to launch an amateur radio satellite, the HAMSAT. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) launched the microsatellite as an auxiliary payload on the PSLV-6.[11]

Licence[]

The Indian Wireless Telegraph (Amateur Service) Rules, 2009 lists two licence categories:[12]

- Amateur Wireless Telegraph Station Licence (General)

- Amateur Wireless Telegraph Station Licence (Restricted)

After passing the examination, the candidate must then clear a police interview. After clearance, the WPC grants the licence along with the user-chosen call sign.[13] This procedure can take up to 12 months.[13]

| Licence category | Age[12] | Power[14] | Examination.[15][16] | Privileges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amateur Wireless Telegraph Station Licence (Restricted Grade) (Formerly Grade II) | 12 | 10 W on VHF and UHF

50 W on HF |

Minimum score of 40% in each section of the written examination, and 50% overall. | Terrestrial radiotelephony transmission in VHF and UHF frequency bands and 12 HF Bands. |

| Amateur Wireless Telegraph Station Licence (General Grade) (Formerly Grade I and Advanced) | 12 | 25 W on VHF and UHF

400 W on HF |

Minimum score of 50% in each section of the written examination, and 55% overall. In addition, a demonstration of proficiency in sending and receiving Morse code at eight words a minute. | Radiotelegraphy and radiotelephony transmission VHF and UHF frequency bands and 12 HF Bands. |

Examination[]

Amateur Station Operator's Certificate or ASOC is the examination that needs to be passed to receive an amateur radio licence in India.[17] The exam is conducted by the Wireless and Planning and Coordination Wing (WPC) of the Ministry of the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology.[18] The examination is held monthly in Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai, every two months in Ahmedabad, Nagpur and Hyderabad, and every four months in some smaller cities.[19] The licence may be awarded to an individual or a club station operated by a group of licensed amateur radio operators.

The exam consists of two parts:[20][21]

- Part I – Written Test

- Section I: Radio Theory and Practice

- Section 2 : Regulations

- Part II – Morse (Not required for Restricted Grade)

- Section 1 : Morse Receiving and Sending : (Speed: 8 words per minute)

- Section 2 : Morse Receiving and Sending : (Speed: 8 words per minute)

The maximum number of marks that a candidate can secure is 100. To pass the examination, a candidate must score a minimum of 40 (50 for Grade I) in each written section, and 50 (55 for Grade I) in aggregate for a pass.[15]

The application and licensing procedures are done online through WPC portal https://saralsanchar.gov.in/

Radio theory and practice[]

The Radio theory and practice syllabus includes eight subtopics:[20]

The first subtopic is the elementary theory of electricity that covers topics on conductors, resistors, Ohm's Law, power, energy, electromagnets, inductance, capacitance, types of capacitors and inductors, series and parallel connections for radio circuits. The second topic is the elementary theory of alternating currents. Portions include sinusoidal alternating quantities such as peak values, instantaneous values, RMS average values, phase; electrical resonance, and quality factor for radio circuits. The syllabus then moves on to semiconductors, specifically the construction and operation of valves, also known as vacuum tubes. Included in this portion of the syllabus are thermionic emissions with their characteristic curves, diodes, triodes and multi-electrode valves; and the use of valves as rectifiers, oscillators, amplifiers, detectors and frequency changers, stabilisation and smoothing.

Radio receivers is the fourth topic that covers the principles and operation of TRF receivers and Superheterodyne receivers, CW reception; with receiver characteristics such as sensitivity, selectivity and fidelity; Adjacent-channel interference and image interference; AGC and squelch; and signal to noise ratio (S/R). Similarly, the next topic on transmitters covers the principles and operation of low power transmitters; oscillators such as the Colpitts oscillator, Hartley oscillator, crystal oscillators, and stability of oscillators.

The last three topics deal with radio propagation, aerials, and frequency measurement. Covered are topic such as wavelength, frequency, nature and propagation of radio waves; ground and sky waves; skip distance; and fading. Common types of transmitting and receiving aerials such as Yagi antennas, and radiation patterns, measurement of frequency and use of simple frequency meters conclude the topic.

Regulations[]

Knowledge of the Indian Wireless Telegraph Rules and the Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Rules are essential and always tested.[20] The syllabus also includes international radio regulations related to the operation of amateur stations with emphasis on provisions of radio regulation nomenclature of the frequency and wavelength, frequency allocation to amateur radio service, measures to prevent harmful interference, standard frequency and time signals services across the world, identification of stations, distress and urgency transmissions, amateur stations, phonetic alphabets, and figure code are the other topics included in the portion.

Also included in the syllabus are Q codes such as QRA, QRG, QRH, QRI, QRK, QRL, QRM, QRN, QRQ, QRS, QRT, QRU, QRV, QRW, QRX, QRZ, QSA, QSB, QSL, QSO, QSU, QSV, QSW, QSX, QSY, QSZ, QTC, QTH, QTR, and QUM; and CW abbreviations and prosigns such as AA, AB, AR, AS, C, CFM, CL, CQ, DE, K, NIL, OK, R, TU, VA, WA, and WB.

Morse[]

The syllabus includes the following Morse code characters: all alphabets, numbers, prosigns, and punctuations such as the full-stop; comma; semi-colon; break sign; hyphen and question mark.[20]

- Receiving

- For Grade II, the test piece consists of a passage of 125 letters, five letters counting as one word. Candidates are required to copy for five minutes at the speed of five words per minute, international Morse signals from an audio oscillator keyed either manually or automatically. A short practice piece is sent at the prescribed speed before the start of the test. More than five errors disqualifies a candidate. For Grade I, the test piece consists of a passage of 300 characters: letters, figures, and punctuations. The average words contain five characters and each figure and punctuation is counted as two characters. Candidates have to receive for five consecutive minutes at a speed of 12 words per minute.

- Sending

- For Grade II, the test piece consists of 125 letters, with five letters forming one word. Candidates are required to transmit by using a Morse key for five consecutive minutes at the minimum speed of five words per minute. A short practice piece is allowed before the test. Candidates are not allowed more than one attempt in the test. More than five uncorrected errors disqualifies a candidate. For Grade I, the speed sent is 12 words per minute.

| Place | Month |

|---|---|

| Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai | Every month |

| Ahmedabad, Hyderabad and Nagpur | January, March, June, August, October and December |

| Ahmedabad, Nagpur, Hyderabad, Ajmer, Bangalore, Darjeeling, Gorakhpur, Jalandhar, Goa (Betim), Mangalore, Shillong, , Srinagar, Dibrugarh, Visakhapatnam, and Thiruvananthapuram. | January, April, July and October |

Fees[]

| Grade | 20 Years | Lifetime |

|---|---|---|

| General Grade | 1000 | 2000 |

| Restricted Grade | 1000 | 2000 |

Reciprocal licensing and operational restrictions[]

Indian amateur radio exams can only be taken by Indian citizens. Foreign passport holders can apply for reciprocal Indian licences based upon a valid amateur radio call-sign from their country of residence.[23]

Indian amateur radio licences always bear mention of location of transmitting equipment. Portable and mobile amateur radio stations require explicit permission from WPC.[24]

Amateur radio operators from United States of America do not have automatic reciprocity in India. The use of US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) call-signs is prohibited under Indian law.[25]

Call-signs[]

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) has divided all countries into three regions; India is located in ITU Region 3. These regions are further divided into two competing zones, the ITU and the CQ. Mainland India and the Lakshadweep Islands come under ITU Zone 41 and CQ Zone 22, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands under ITU Zone 49 and CQ Zone 26. The ITU has assigned to India call-sign blocks 8TA to 8YZ, VUA to VWZ, and ATA to AWZ.[26][27]

The WPC allots individual call-signs. Indian amateur radio operators are allotted only the VU call-sign prefix. The V or Viceroy, series prefix was allotted to British colonies.[28] at the 1912 London International Radiotelegraphic Convention.[29]

VU call-signs are listed according to licence grade: for General (formerly the Advanced Grade and Grade–I) licence holders, the call-sign prefix is VU2; for Restricted (formerly Grade–II and Grade–II Restricted) licence holders, the prefix is VU3. The VU3 prefix has also been granted to foreigners operating in India. As of 2011, call-signs consist of only letters, not numerals, and can be either two or three characters long. Examples of Indian amateur radio call-signs are "VU2XY" and "VU2XYZ".[citation needed]

In addition to individual and club call-signs, the WPC allots temporary call-signs for contests and special events. For example, in November 2007, the WPC temporarily allotted the prefixes AT and AU to selected ham operators to mark the anniversary of the birth of radio scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose.[30] The Indian Union territory (UT) of Andaman and Nicobar Islands are assigned the prefix VU4 and the UT of Lakshadweep is assigned VU7.

Defunct call-signs include CR8 (for Portuguese India), FN8 (for French India), and AC3 (for the former kingdom of Sikkim, which merged with India in 1975).[31]

Organisation

The WPC is the only authorised body responsible for regulating amateur radio in India. The WPC has its headquarters in New Delhi with regional headquarters and monitoring stations in Mumbai (Bombay), Kolkata (Calcutta), and Chennai (Madras). It also has monitoring stations in Ahmedabad, Nagpur, Hyderabad, Ajmer, Bangalore, Darjeeling, Gorakhpur, Jalandhar, Goa (Betim), Mangalore, Shillong, Ranchi, Srinagar, Dibrugarh, Visakhapatnam, and Thiruvananthapuram.[19] Set up in 1952, the organization is responsible for conducting exams, issuing licences, allotting frequency spectrum, and monitoring the airwaves. It is also responsible for maintaining the rules and regulations on amateur radio.

In India, amateur radio is governed by the Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Rules, 1978, the Indian Wireless Telegraph Rules, the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 and the Information Technology Act, 2000. The WPC is also responsible for coordinating with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Intelligence Bureau in running background checks before issuing amateur radio licences.[32]

Allotted spectrum[]

The following frequency bands are permitted by the WPC for use by amateur radio operators in India.[14]

| Band | Frequency in MHz | Wavelength |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1.820–1.860 | 160 m |

| 7 | 3.500–3.700 | 80 m |

| 7 | 3.890–3.900 | 80 m |

| 7 | 7.000–7.200 | 40 m |

| 7 | 10.100–10.150 | 30 m |

| 7 | 14.000–14.350 | 20 m |

| 7 | 18.068–18.168 | 17 m |

| 7 | 21.000–21.450 | 15 m |

| 7 | 24.890–24.990 | 12 m |

| 7 | 28.000–29.700 | 10 m |

| 8 | 50–52 | 6 m |

| 8 | 144–146 | 2 m |

| 9 | 434–438 | 70 cm |

| 9 | 1260–1300 | 23 cm |

| 10 | 3300–3400 | 9 cm |

| 10 | 5725–5840 | 5 cm |

Awareness drives[]

Indian amateur radio operators number approximately 22,000. Amateur radio clubs across the country offer training courses for the Amateur Station Operator's Certificate. People interested in the hobby would be advised to get in touch with a local radio club or a local amateur radio operator who can direct them to a club that organises training programmes.

Activities and events[]

Popular events and activities include Amateur Radio Direction Finding, DX-peditions, hamfests, JOTA, QRP operations, Contesting, DX communications, Light House operation, and Islands on Air. One of the most popular activities is Amateur Radio Direction Finding commonly known as a "foxhunt".[13] Several clubs across India regularly organize foxhunts in which participants search for a hidden transmitter around the city.[33] A foxhunt carried out in Matheran near Mumbai in 2005 by the Mumbai Amateur Radio Society was listed in the 2006 Limca Book of Records under the entry "most ham operators on horseback on a foxhunt."[34] Despite being a popular recreational activity among hams, no organization has yet participated in an international event.[35]

Hamfest India is an annual event that serves for social gathering and comparison and sales of radio equipment. Most hamfests feature a flea market, where the attendees buy and sell equipment, generally from and for their personal stations. The event also seeks to raise amateur radio awareness in the host city. In 2008, Gandhinagar hosted the annual hamfest. Bangalore hosted the hamfest in November 2009. The 2011 hamfest was held at Kochi, Kerala.[36]

Ham nets, where amateur radio operators "check into" are regularly conducted across India. Airnet India, Charminar Net, Belgaum Net, and Nite Owl's Net are some of the well-known ham nets in India.[citation needed]

See also[]

- Amateur radio frequency bands in India

- Amateur Station Operator's Certificate

- Citizens Band radio in India

- Amateur radio callsigns of India

References[]

- Note:* Indian call signs do not use numbers as an identifier. This picture is for demonstration purposes only.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ramchandran, Ramesh (3 March 2005). "Government to promote amateur radio". The Tribune. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ Press Trust of India (15 October 2005). "Bachchan, Gandhi style!". Indian Express. Express Group. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Susarla, Ramesh (15 December 2007). "Licence to yak". The Hindu. N. Ram. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Ramchandran, Ramesh (4 January 2005). "Sonia helps bridge communication gap". The Tribune. The Tribune Trust. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Missra, Avinash (1996). Brief History of Amateur Radio in Calcutta. Hamfest India '96 Souvenir. Kolkata.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Regal, Brian (30 September 2005). Radio: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Press. pp. 77/152. ISBN 0-313-33167-7. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williamson, Owen. "The Mahatma's Hams". WorldRadio. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Member Societies". International Amateur Radio Union. Archived from the original on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Missra, Avinash (1996). Brief History of Amateur Radio in Calcutta. Hamfest India '96 Souvenir. Kolkata.

- ^ Verma, Rajesh (1999). "1". ABC of Amateur Radio and Citizen Band (2 ed.). New Delhi: EFY Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. p. 11.

- ^ "AMSAT - VO52 (HAMSAT) Information". AMSAT. 12 May 2005. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Section 5 "The Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Radio) Rules, 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Communications, Government of India. Controller of Publications, Civil Lines, New Delhi. 1979. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Ham operators are a cut above the rest". The Times of India. 21 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Annexure V "The Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Radio) Rules, 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Communications, Government of India. Controller of Publications, Civil Lines, New Delhi. 1979. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Annexure III, Appendix I "The Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Radio) Rules, 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Communications, Government of India. Controller of Publications, Civil Lines, New Delhi. 1979. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Amendment Rules, 2005" (doc). Wireless and Planning and Coordination Wing, Government of India. 9 June 2005. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Section 7 "The Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Radio) Rules, 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Communications, Government of India. Controller of Publications, Civil Lines, New Delhi. 1979. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b VU3WIJ. "An Introduction to Amateur Radio". The Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Rules, 1978. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Appendix II "The Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Radio) Rules, 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Communications, Government of India. Controller of Publications, Civil Lines, New Delhi. 1979. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Rules

- ^ Annexure III, Appendix I, Section 2.3 "The Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Radio) Rules, 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Communications, Government of India. Controller of Publications, Civil Lines, New Delhi. 1979. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Rules, 1978". Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ http://www.vigyanprasar.gov.in/ham/asocrules.htm

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ http://www.arrl.org/reciprocal-permit

- ^ ITU Zone 41 Map (Map). International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ CQ Zone 22 Map (Map). International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Govt yet to free Indian aircraft from colonial past". Indian Express. Express Group. 4 August 2003. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ "Radio Call Letters: May 9, 1913" (PDF). Bureau of Navigation, Department of Commerce, United States. 9 May 1913. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Special callsigns for Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose anniversary". Government of India letter "L-14011/640/ 2007-AMT" dated 2007-09-19". Southmate Amateur Radio Club. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Amateur Radio Old Prefixes & Deleted Entities". ARRL. 7 January 2004. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "WPC Home". Wireless Planning and Coordination Wing. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "HAM club organising 'Fox Hunt'". The Hindu. N. Ram. 6 October 2007. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ editor, Vijaya Ghose.; Limca Team (2006). Limca Book of Records 2006. Limca Books. ISBN 81-902837-3-1. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2008.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Participation of Societies". IARU Region I ARDF Working Group. 2003. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Lifeline Systems in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (India) after the December 2004 Great Sumatra Earthquake and Indian Ocean Tsunami" (PDF). Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. Retrieved 25 July 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

![]() This article incorporates text from the "Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Rules, 1978" in compliance with the Indian Copyright Act, 1957 Section 52 (1)(q)

This article incorporates text from the "Indian Wireless Telegraphs (Amateur Service) Rules, 1978" in compliance with the Indian Copyright Act, 1957 Section 52 (1)(q)

Amendment in Amateur Radio rule 2010 by WPC (actually based on 2009)[1]

Further reading[]

- Verma, Rajesh (1988), ABC of Amateur Radio and Citizen Band, EFY Publications

- Ali, Saad (1985), Guide To Amateur Radio In India, E.M.J. Monteiro

- Verma, Rajesh (1988). "ABC of Amateur Radio and Citizen Band". EFY Publications. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ali, Saad (1985). "Guide To Amateur Radio In India". E.M.J. Monteiro. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links[]

- Amateur radio in India

- Amateur radio licensing