Portuguese India

State of India Estado da Índia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1505–1961 | |||||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||

| Anthem: Hymno Patriótico (1808–1826) "Patriotic Anthem" Hino da Carta (1826–1911) "Hymn of the Charter" A Portuguesa (1911–1961) "The Portuguese" | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Status | Colony of Portugal (1505-1946) Overseas province of Portugal (1946-1961) | ||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity (Catholicism) | ||||||||||||

| Head of State | |||||||||||||

• 1511–1521 | Manuel I of Portugal | ||||||||||||

• 1958–1961 | Américo Tomás | ||||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||||

• 1505-1509 | Francisco de Almeida (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1958–1961 | Manuel António Vassalo e Silva (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Imperialism | ||||||||||||

• Fall of Sultanate of Bijapur | 15 August 1505 | ||||||||||||

• Indian Annexation | 19 December 1961 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

• Total | 4,305 km2 (1,662 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||||

The State of India (Portuguese: Estado da Índia), also referred as the Portuguese State of India (Estado Português da Índia, EPI) or simply Portuguese India (Índia Portuguesa), was a colonial state of the Portuguese Empire founded six years after the discovery of a sea route to the Indian subcontinent by the Kingdom of Portugal. The capital of Portuguese India served as the governing centre of a string of Portuguese fortresses and settlements scattered along the Indian Ocean.

The first viceroy, Francisco de Almeida, established his headquarters at what was then Cochim, the present-day Fort Cochin, subsequent Portuguese governors were not always of viceroy rank. After 1510, the capital of the Portuguese viceroyalty was transferred to Velhas Conquistas (Old Conquests area) of present-day Goa and Damaon.[1] Present-day Bombay (Mumbai) was part of Portuguese India as Bom Baim until it was ceded to the British Crown in 1661, who in turn leased Bombay to the East India Company. Until the 18th century, the Governor in Velha Goa had authority over all possessions in and around the Indian Ocean, from southern Africa to southeast Asia, what were collectively called the Portuguese East Indies. In 1752, Mozambique got its own separate government, and in 1844 the Portuguese government of India stopped administering the territory of Macao, Solor, and Timor, Portugal's authority was confined to the colonial holdings on the Konkan and Malabar coasts of Western India.

At the time of the British Raj's dissolution in 1947, Portuguese India was subdivided into three districts located on modern-day India's western coast, sometimes referred to collectively as Goa: namely Goa; Damão, which included the inland enclaves of Dadra and Nagar Haveli; and Diu. Portugal lost effective control of the enclaves of Dadra and Nagar Haveli in 1954, and finally the rest of the overseas territory in December 1961, when it was annexed by India under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. In spite of this, Portugal only recognised Indian control in 1974, after the Carnation Revolution and the fall of the Estado Novo regime, by a treaty signed on 31 December 1974.[2]

Early history[]

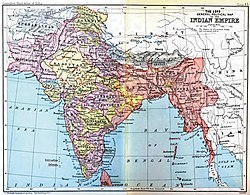

| Colonial India | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Vasco da Gama lands in India[]

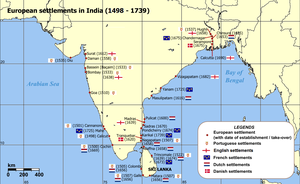

The first Portuguese encounter with the subcontinent was on 20 May 1498 when Vasco da Gama reached Calicut on the Malabar Coast. Anchored off the coast of Calicut, the Portuguese invited native fishermen on board and immediately bought some Indian items. One Portuguese accompanied the fishermen to the port and met with a Tunisian Muslim. On the advice of this man, Gama sent a couple of his men to Ponnani to meet with ruler of Calicut, the Zamorin. Over the objections of Arab merchants, Gama managed to secure a letter of concession for trading rights from the Zamorin, Calicut's ruler. But, the Portuguese were unable to pay the prescribed customs duties and price of his goods in gold.[3]

Later Calicut officials temporarily detained Gama's Portuguese agents as security for payment. This, however, annoyed Gama, who carried a few natives and sixteen fishermen with him by force.[4]

Nevertheless, Gama's expedition was successful beyond all reasonable expectation, bringing in cargo that was worth sixty times the cost of the expedition.

Pedro Álvares Cabral[]

Pedro Álvares Cabral sailed to India, marking the arrival of Europeans to Brazil on the way, to trade for pepper and other spices, negotiating and establishing a factory at Calicut, where he arrived on 13 September 1500. Matters worsened when the Portuguese factory at Kozhikode was attacked by surprise by the locals, resulting in the death of more than fifty Portuguese.[5] Cabral was outraged by the attack on the factory and seized ten Arab merchant ships anchored in the harbour, killing about six hundred of their crew and confiscating their cargo before burning the ships. Cabral also ordered his ships to bombard Calicut for an entire day in retaliation for the violation of the agreement. In Cochin and Cannanore Cabral succeeded in making advantageous treaties with the local rulers. Cabral started the return voyage on 16 January 1501 and arrived in Portugal with only 4 of 13 ships on 23 June 1501.

The Portuguese built the Pulicat fort in 1502, with the help of the Vijayanagar ruler.[clarification needed]

Vasco da Gama sailed to India for a second time with 15 ships and 800 men, arriving at Calicut on 30 October 1502, where the ruler was willing to sign a treaty. Gama this time made a call to expel all Muslims (Arabs) from Calicut which was vehemently turned down. He bombarded the city and captured several rice vessels.[6] He returned to Portugal in September 1503.

Francisco de Almeida[]

On 25 March 1505, Francisco de Almeida was appointed Viceroy of India, on the condition that he would set up four forts on the southwestern Indian coast: at Anjediva Island, Cannanore, Cochin and Quilon.[7] Francisco de Almeida left Portugal with a fleet of 22 vessels with 1,500 men.[7]

On 13 September, Francisco de Almeida reached Anjadip Island, where he immediately started the construction of Fort Anjediva.[7] On 23 October, with the permission of the friendly ruler of Cannanore, he started building St. Angelo Fort at Cannanore, leaving Lourenço de Brito in charge with 150 men and two ships.[7]

Francisco de Almeida then reached Cochin on 31 October 1505 with only 8 vessels left.[7] There he learned that the Portuguese traders at Quilon had been killed. He decided to send his son Lourenço de Almeida with 6 ships, who destroyed 27 Calicut vessels in the harbour of Quilon.[7] Almeida took up residence in Cochin. He strengthened the Portuguese fortifications of Fort Manuel on Cochin.

The Zamorin prepared a large fleet of 200 ships to oppose the Portuguese, but in March 1506 Lourenço de Almeida (son of Francisco de Almeida) was victorious in a sea battle at the entrance to the harbour of Cannanore, the Battle of Cannanore, an important setback for the fleet of the Zamorin. Thereupon Lourenço de Almeida explored the coastal waters southwards to Colombo, in what is now Sri Lanka. In Cannanore, however, a new ruler, hostile to the Portuguese and friendly with the Zamorin, attacked the Portuguese garrison, leading to the Siege of Cannanore.

In 1507 Almeida's mission was strengthened by the arrival of Tristão da Cunha's squadron. Afonso de Albuquerque's squadron had, however, split from that of Cunha off East Africa and was independently conquering territories in the Persian Gulf to the west.

In March 1508 a Portuguese squadron under command of Lourenço de Almeida was attacked by a combined Mameluk Egyptian and Gujarat Sultanate fleet at Chaul and Dabul respectively, led by admirals Mirocem and Meliqueaz in the Battle of Chaul. Lourenço de Almeida lost his life after a fierce fight in this battle. Mamluk-Indian resistance was, however, to be decisively defeated at the Battle of Diu.

Afonso de Albuquerque and later governors[]

In the year 1509, Afonso de Albuquerque was appointed the second governor of the Portuguese possessions in the East. A new fleet under Marshal Fernão Coutinho arrived with specific instructions to destroy the power of Zamorin of Calicut. The Zamorin's palace was captured and destroyed and the city was set on fire. The king's forces rallied, killing Coutinho and wounding Albuquerque. Albuquerque relented and entered into a treaty with the Zamorin in 1513 to protect Portuguese interests in Malabar. Hostilities were renewed when the Portuguese attempted to assassinate the Zamorin sometime between 1515 and 1518. In 1510, Afonso de Albuquerque defeated the Bijapur sultan with the help of the Hindu Vijayanagar empire, leading to the establishment of a permanent settlement in Velha Goa (or Old Goa). The Southern Province, also known simply as Goa, was the headquarters of Portuguese India, and seat of the Portuguese viceroy who governed all the Portuguese possessions in Asia, known as the Portuguese East Indies until the onset of the Hispano-Dutch War and the Luso-Dutch War.

There were Portuguese settlements in and around Mylapore. The Luz Church in Mylapore, Madras (Chennai) was the first church that the Portuguese built in Madras in 1516. Later in 1522, the São Tomé church was built by the Portuguese.

The Portuguese acquired several territories from the Sultans of Gujarat: Damaon (occupied in 1531, formally ceded 1539); Salsette, Bombay, Baçaim (Bassein) (occupied in 1534); and Diu (ceded 1535).

These possessions became the Northern Province of Portuguese India, which extended almost 100 km (62 mi) along the coast from Damaon to Chaul, and in places 30–50 km (19–31 mi) inland. The province was ruled from the fortress-town of Baçaim (Fort Bassein).

In 1526, under the viceroyship of Lopo Vaz de Sampaio, the Portuguese took possession of Mangalore. The territory included parts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi in Karnataka state, and Kasaragod in Kerala state (South Canara). Mangalore was named the islands of O Padrão de Santa Maria; later came to be known as St. Mary's Islands. In 1640, the Keladi Nayaka Kingdom defeated the Portuguese. Shivappa Nayaka destroyed the Portuguese political power in the Kanara region by capturing all the Portuguese forts of the coastal region.[8][full citation needed]

In 1546, Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier requested the institution of the Goa Inquisition for the "New Christians" in a letter dated 16 May 1546 to King John III of Portugal.[9] Various non-Christian communities were officially persecuted by the Portuguese colonisers.[10][11]

By the start of the 17th century, the population of Goa and the surrounding areas was about 250,000.[13] Holding this strategic land against repeated attacks by the Indian states required constant infusions of men and material; for instance, 25,000 soldiers died in Goa from 1604 to 1634. However the quality of these men was low compared to those in Europe (often they were beggars, jailbirds, or people forcibly taken off the streets of Lisbon) and they were never very numerous or well-organized (proper regiments were not formed until the 18th century; there was no standardized weaponry and companies would disband outside of campaign seasons). Portugal's important victories, such as the battle of Cochin in 1504, the defense of Diu in 1509, the conquest of Goa in 1510, the defenses of Diu in 1538 and 1546, and the defense of Goa in 1571 were always accomplished with a bare handful of men. In their largest deployments, the Portuguese could field perhaps 2,000 to 3,000 European and mestizo troops supported by a similar amount of local auxiliaries, while the larger Indian states could field tens of thousands each. Portuguese superiority in military technology (especially in regards to ships and artillery), training (especially in the skill of their gunners), and tactics, combined with the disunity of the Indian states opposing them, allowed them to keep their position and consistently win their wars.[14]

Bombay (present-day Mumbai) was given to Britain in 1661 as part of the Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza's dowry to Charles II of England. Most of the Northern Province was lost to the Maratha Confederacy in 1739 when the Maratha General Chimaji Appa attacked and plundered Fort Bassein in the Battle of Bassein. Later on Portugal acquired Dadra and Nagar Haveli in 1779.

Goa was briefly occupied by the British from 1799 to 1813.[15]

In 1843 the capital was shifted to Panjim, then renamed Nova Goa, when it officially became the administrative seat of Portuguese India, replacing the city of Velha Goa (now Old Goa), although the Viceroys lived there already since 1 December 1759. Before moving to the city, the viceroy remodelled the fortress of Adil Khan, transforming it into a palace.

The Portuguese also shipped over many Órfãs d'El-Rei to Portuguese colonies in the Indian peninsula, Goa in particular. Órfãs d'El-Rei literally translates to Orphans of the King, and they were Portuguese girl orphans sent to overseas colonies to marry either Portuguese settlers or natives with high status.

Thus there are Portuguese footprints all over the western and eastern coasts of the Indian peninsula, though Goa became the capital of Portuguese Goa from 1530 onward until the annexation of Goa proper and the entire Estado da Índia Portuguesa, and its merger with India in 1961.

1947 to 1961[]

On 24 July 1954 an organisation called "The United Front of Goans" took control of the enclave of Dadra. The remaining territory of Nagar Haveli was seized by Azad Gomantak Dal on 2 August 1954.[16] The decision given by the International Court of Justice at The Hague, regarding access to Dadra and Nagar Haveli, was an impasse.[17]

| 1 Escudo (1959) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obverse: Lettering "ESTADO·DA·INDIA", face value with Coat of arms of Portugal in the center. | Reverse: Lettering "REPÚBLICA · PORTUGUESA", year and Coat of arms of Portugal in the center. |

| 6,000,000 coins minted. This coin was from Portuguese State of India. | |

From 1954, the Satyagrahis (peaceful protesters) against Portuguese rule, outside Goa and Damaon's borders were violently suppressed through brute force.[18] Many internal revolts were quelled by the use of force and leaders extrajudicially murdered or jailed. As a result, India broke off diplomatic relations with Portugal, closed its Consulate-General in Panjim[19] and demanded that Salazar regime should close its delegation in New Delhi.[20] India also imposed an economic embargo against the territories of Portuguese Goa.[21] The Indian Government adopted a diplomatic "wait and watch" approach from 1955 to 1961 with numerous representations to the Portuguese Salazar dictatorship, and made attempts to highlight the issue of decolonisation before the international community.[22]

To facilitate the transport of people and goods to and from the Indian enclaves, the Salazar dictatorship established an airline, Transportes Aéreos da Índia Portuguesa,[23] and airports at Goa, Daman and Diu.

Finally, in December 1961, India militarily invaded the remaining Portuguese possessions of Goa and Damaon, where regardless of the odds the Portuguese forces put up a fight.[24][25] Portuguese forces had been given orders to either defeat the invaders or die.[citation needed] Only meager resistance was offered due to the Portuguese army's poor firepower and size (only 3,300 men), against a fully armed Indian force of over 30,000 with full air and naval support.[26][27] The Governor of Portuguese India signed the Instrument of Surrender[28] on 19 December 1961, ending 450 years of Portuguese rule in India.

Post-annexation[]

Status of the new territories[]

Free Dadra and Nagar Haveli existed as a de facto independent entity from its independence in 1954 until its merger with the Republic of India in 1961.[29]

Following the annexation of Goa, Daman and Diu, the new territories became union territories within the Indian Union as Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Goa, Daman and Diu. Maj. Gen. K. P. Candeth was declared as military governor of Goa, Daman and Diu. Goa's first general elections were held in 1963.

In 1967 a referendum was conducted, where voters decided whether to merge Goa into the Mahratti majority state of Maharashtra, the pro-Konkani faction eventually won after many protests against the pro-Marathi faction led by Dayanand Bandodkar.[30] However full statehood was not conferred immediately, and it was only on 30 May 1987 that Goa became the 25th state of the Indian Union, with Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu being separated, continue to be administered as Union Territories.[31]

The most drastic changes in Portuguese India after 1961 were the introduction of democratic elections, as well as the replacement of Portuguese with English as the general language of government and education.[32] In 1987, Konkani in the Devanagari script became the official language of the union territory of Goa, Daman and Diu.[33] The Indians allowed certain Portuguese institutions to continue unchanged. Amongst these were the land ownership system of the comunidade, where land was held by the community and was then leased out to individuals. Goans under Indian Government left the Portuguese Goa civil code unchanged, hence Goa and Damaon today remain as the only territories in India with a common civil code that does not depend on religion.[34]

Citizenship[]

The Citizenship Act of 1955 granted the government of India the authority to define citizenship in the Indian union. In exercise of its powers, the government passed the Goa, Daman and Diu (Citizenship) Order, 1962 on 28 March 1962 conferring Indian citizenship on all persons born on or before 20 December 1961 in Goa, Daman, and Diu.[35]

Indo-Portuguese relations[]

Portugal's Salazar dictatorship did not recognise India's sovereignty over the annexed territories, and established a government-in-exile for the territories,[36] which continued to be represented in the Portuguese National Assembly.[37][full citation needed] After 1974's Carnation Revolution, the new Portuguese government recognised Indian sovereignty over Goa, Daman and Diu,[38] and the two states restored diplomatic relations. Portugal automatically gives citizens of the former Portuguese-India its citizenship[39] and opened a consulate in Goa in 1994.[40]

Portuguese cemetery in Kollam (Quilon)[]

Kollam (originally Desinganadu, a prominent seaport in ancient India) became a Portuguese settlement; in 1519 they built a cemetery at Tangasseri in Quilon city. After a Dutch invasion, they also buried their dead there. The Pirates of Tangasseri formerly inhabited the cemetery. Remnants of this cemetery are still in existence today at Tangasseri. The site is very close to Tangasseri Lighthouse and St Thomas Fort, which are on the list of centrally protected monuments under the control of Archaeological Survey of India.[41][42][43][44]

Postal history[]

Early postal history of the colony is obscure, but regular mail is known to have been exchanged with Lisbon from 1825 onwards. Portugal had a postal convention with Great Britain, so much mail was probably routed through Bombay and carried on British packets. Portuguese postmarks are known from 1854 when a post office was opened in Goa.

The last regular issue for Portuguese India was on 25 June 1960, for the 500th anniversary of the death of Prince Henry the Navigator. Stamps of India were first used on 29 December 1961, although the old stamps were accepted until 5 January 1962. Portugal continued to issue stamps for the lost colony but none were offered for sale in the colony's post offices, so they are not considered valid stamps.

Dual franking was tolerated from 22 December 1961 until 4 January 1962. Colonial (Portuguese) postmarks were tolerated until May 1962.

See also[]

| Outline of South Asian history |

|---|

|

- Portuguese Empire

- Estado Novo (Portugal)

- Indo-Portuguese creoles

- List of governors of Portuguese India

- Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (archives in Lisbon documenting Portuguese Empire, including India)

- Portuguese Indian Rupia

- Portuguese Indian Escudo

- Goa liberation movement

- Goan civil code

- Cuncolim Revolt

- Portuguese Bombay and Bassein

- Portuguese Ceylon

- Colonialism in India

References[]

- ^ "Capital". myeduphilic. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Treaty Between the Government of India and the Government of the Republic of Portugal on Recognition of India's Sovereignty over Goa, Daman, Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Related Matters". www.commonlii.org. 1974.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. (2006). Calicut: The City of Truth Revisited. Calicut University Publications. p. 198. ISBN 9788177481044.

- ^ . The incident is mentioned by Camões in The Lusiads, wherein it is stated that the Zamorin "showed no signs of treachery" and that "on the other hand, Gama's conduct in carrying off the five men he had entrapped on board his ships is indefensible".

- ^ Chalmers, Alexander (1810). English Translations: From Modern and Ancient Poems. J. Johnson.

- ^ Sreedhara Menon, A. (1967). A Survey of Kerala History. Kottayam: D. C. Books. p. 152.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Logan, William (2000). Malabar Manual. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120604469.

- ^ Portuguese Studies Review (ISSN 1057-1515) (Baywolf Press) p.35

- ^ Cuoto, Maria Aurora (2005). Goa: A Daughter's Story. Penguin Books. pp. 109–121, 128–131.

- ^ Glenn, Ames. Portugal and its Empire, 1250–1800 (Collected Essays in Memory of Glenn J. Ames. The Portuguese Studies Review at Trent University Press. pp. 12–15.

- ^ Walker, Timothy D. (2021). "Contesting Sacred Space in the Estado da India: Asserting Cultural Dominance over Religious Sites in Goa". Ler História (78): 111–134. doi:10.4000/lerhistoria.8618. ISSN 0870-6182.

- ^ Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.

- ^ M.N. Pearson. "The New Cambridge History of India: The Portuguese in India." 1988. Pages 92-93: "In 1524 there were 450 Portuguese householders in Goa city, and in 1540 about 1,800. The former figure refers to 'pure' Portuguese, while the latter includes descendants of Portuguese and local women, in other words mestizos. There were also 3,600 soldiers in the town in 1540. Later in the 1540s, at the time of St Francis Xavier, the city population included 10,000 Indian Christians, 3,000-4,000 Portuguese, and many non-Christians, while outside the city the rest of Ilhas contained 50,000 inhabitants, 80 percent of them Hindu. Recent estimates put the city population at 60,000 in the 1580s, and about 75,000 at 1600, the latter figure including 1,500 Portuguese and mestizos, 20,000 Hindus, and the rest local Christians, Africans, and others. In the 1630s the total population of the Old Conquests — Ilhas, Bardes and Salcette — was perhaps a little more than a quarter of a million... Casualties in the endless skirmishes with Malabaris and others were often substantial. Cholera and malaria also took their toll; one estimate claims that from 1604 to 1634, 25,000 soldiers died in the Royal Hospital in Goa."

- ^ Pearson, p. 56-59.

- ^ "Catalogue Description: 'The British Occupation of the Portuguese Settlements in India, Goa, Diu, Damaun,..." discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. The National Archives.

- ^ Mascarenhas, Lambert. "Goa's Freedom Movement". Archived from the original on 14 February 2012.

- ^ (PDF). 22 December 2011 https://web.archive.org/web/20111222171240/http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/32/4523.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Singh, Satyindra (1992). "Blueprint to Bluewater, The Indian Navy, 1951–65" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2006.

- ^ Ali, B. Sheikh (1986). Goa Wins Freedom: Reflections and Reminiscences. Goa University. p. 154. ISBN 9788185571003.

- ^ Esteves, Sarto (1966). Goa and Its Future. Manaktalas. p. 88.

- ^ Prabhakar, Peter Wilson (2003). Wars, Proxy-wars and Terrorism: Post Independent India. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 39. ISBN 9788170998907.

- ^ "Lambert Mascarenhas, "Goa's Freedom Movement," excerpted from Henry Scholberg, Archana Ashok Kakodkar and Carmo Azevedo, Bibliography of Goa and the Portuguese in India New Delhi, Promilla (1982)". Archived from the original on 14 February 2012.

- ^ De Souza, Teotonio R. (1990). Goa Through the Ages. Goa University Publications Series No. 6. vol. 2: An Economic History. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. p. 276. ISBN 9788170222590.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "Liberation of Goa". Government Polytechnic of Goa. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "The Liberation of Goa: 1961". Bharat Rakshak, a Consortium of Indian Military Websites. Archived from the original on 28 August 2006.

- ^ Pillarisetti, Jagan. "The Liberation of Goa: 1961". Bharat Rakshak, a Consortium of Indian Military Websites. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012.

- ^ "Liberation of Goa, Goa Liberation Day". Maps of India.

- ^ "Dossier Goa – A Recusa do Sacrifício Inútil". Shvoong.com.

- ^ Gupta, K. R. Amita; Gupta, Amita (2006). Concise Encyclopaedia of India. Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 1214. ISBN 9788126906390.

- ^ "But Not Gone". Time. 27 January 1967. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008.

- ^ Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David (2 September 2003). The Territories and States of India. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781135356255.

- ^ Miranda, Rocky V. (2007). "Konkani". In Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 735. ISBN 9781135797119.

- ^ "The Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act, 1987" (PDF), Manual of Goa Laws, III, pp. 487–492

- ^ "Portuguese Civil Code is No Model for India". The Times of India. TNN. 28 November 2009.

- ^ "Gangadhar Yashwant Bhandare vs Erasmo Jesus De Sequiria". manupatra. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Goa To Have An Exile Government". The Age. 5 January 1962. p. 4.

- ^ Asian Recorder, 8, 1962, p. 4490

- ^ "Treaty on Recognition of India's Sovereignty over Goa, Daman and Diu, Dadar and Nagar Haveli Amendment, 14 Mar 1975". mea.gov.in.

- ^ Barbosa, Alexandre Moniz (15 January 2014). "Portuguese Nationality is Fundamental Right by Law". The Times of India.

- ^ "Portuguese Citizens Cannot Contest Polls: Faleiro". The Hindu. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Colonial Voyage – Tangasseri". Mathrubhumi. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Tangasseri – OOCITIES". OOCITIES. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Archaeological site and remains". Archaeological Survey of India – Thrissur Circle. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Tangasseri: A Brief History". Rotary Club of Tangasseri. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

Further reading[]

| Library resources about Portuguese India |

- Andrada (undated). The Life of Dom John de Castro: The Fourth Vice Roy of India. Jacinto Freire de Andrada. Translated into English by Peter Wyche. (1664). Henry Herrington, New Exchange, London. Facsimile edition (1994) AES Reprint, New Delhi. ISBN 81-206-0900-X.

- Panikkar, K. M. (1953). Asia and Western dominance, 1498–1945, by K.M. Panikkar. London: G. Allen and Unwin.

- Panikkar, K. M. 1929: Malabar and the Portuguese: being a history of the relations of the Portuguese with Malabar from 1500 to 1663

- Priolkar, A. K. The Goa Inquisition (Bombay, 1961).

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portuguese rule in India. |

- ColonialVoyage.com – History of the Portuguese and the Dutch in Ceylon, India, Malacca, Bengal, Formosa, Africa, Brazil.

- Biographical entries on Portuguese viceroys and governors of India (1550-1640) in Portuguese - [1]

Coordinates: 2°11′20″N 102°23′4″E / 2.18889°N 102.38444°E

- Portuguese India

- Empires and kingdoms of India

- Former Portuguese colonies

- States and territories established in 1505

- Colonial states of the Portuguese Empire

- States and territories disestablished in 1961

- History of Kerala

- Former countries in South Asia

- History of Goa

- Former colonies in Asia

- 1505 establishments in Portuguese India

- 1961 disestablishments in Portuguese India

- Portuguese colonisation in Asia