Ambergris

Ambergris (/ˈæmbərɡriːs/ or /ˈæmbərɡrɪs/, Latin: ambra grisea, Old French: ambre gris), ambergrease, or grey amber, is a solid, waxy, flammable substance of a dull grey or blackish colour produced in the digestive system of sperm whales.[1] Freshly produced ambergris has a marine, fecal odor. It acquires a sweet, earthy scent as it ages, commonly likened to the fragrance of rubbing alcohol without the vaporous chemical astringency.[2]

Ambergris has been highly valued by perfume makers as a fixative that allows the scent to endure much longer, although it has been mostly replaced by synthetic ambroxide.[3] Dogs are attracted to the smell of ambergris and are sometimes used by ambergris searchers.[4]

Etymology[]

The word ambergris comes from the Old French "ambre gris" or "grey amber".[5][6] The word "amber" comes from the same source, but it has been applied almost exclusively to fossilized tree resins from the Baltic region since the late 13th century in Europe.

Furthermore, the word "amber" is derived from the Middle Persian (Pahlavi) word ambar (variants: ’mbl, 'nbl).

Formation[]

Ambergris is formed from a secretion of the bile duct in the intestines of the sperm whale, and can be found floating on the sea or washed up on coastlines. It is sometimes found in the abdomens of dead sperm whales.[5] Because the beaks of giant squids have been discovered within lumps of ambergris, scientists have theorized that the substance is produced by the whale's gastrointestinal tract to ease the passage of hard, sharp objects that it may have eaten.

Ambergris is passed like fecal matter. It is speculated that an ambergris mass too large to be passed through the intestines is expelled via the mouth, but this remains under debate.[7] Ambergris takes years to form. Christopher Kemp, the author of Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris, says that it is only produced by sperm whales, and only by an estimated one percent of them. Ambergris is rare; once expelled by a whale, it often floats for years before making landfall.[8] The slim chances of finding ambergris and the legal ambiguity involved led perfume makers away from ambergris, and led chemists on a quest to find viable alternatives.[9]

Ambergris is found in primarily the Atlantic Ocean and on the coasts of South Africa; Brazil; Madagascar; the East Indies; The Maldives; China; Japan; India; Australia; New Zealand; and the Molucca Islands. Most commercially collected ambergris comes from the Bahamas in the Atlantic, particularly New Providence. In 2021, fishermen found a 280 pound piece of ambergris off the coast of Yemen, valued at US$1.5 million.[10] Fossilised ambergris from 1.75 million years ago has also been found.[11]

Physical properties[]

Ambergris is found in lumps of various shapes and sizes, usually weighing from 15 grams (1⁄2 ounce) to 50 kilograms (110 pounds) or more.[5] When initially expelled by or removed from the whale, the fatty precursor of ambergris is pale white in color (sometimes streaked with black), soft, with a strong fecal smell. Following months to years of photodegradation and oxidation in the ocean, this precursor gradually hardens, developing a dark grey or black color, a crusty and waxy texture, and a peculiar odor that is at once sweet, earthy, marine, and animalic. Its scent has been generally described as a vastly richer and smoother version of isopropanol without its stinging harshness. In this developed condition, ambergris has a specific gravity ranging from 0.780 to 0.926. It melts at about 62 °C (144 °F) to a fatty, yellow resinous liquid; and at 100 °C (212 °F) it is volatilised into a white vapor. It is soluble in ether, and in volatile and fixed oils.[5]

Chemical properties[]

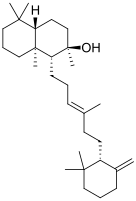

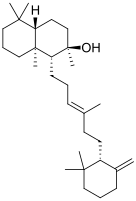

Ambergris is relatively nonreactive to acid. White crystals of a terpene known as ambrein, discovered by Ružička and Fernand Lardon in 1946,[12][13][14] can be separated from ambergris by heating raw ambergris in alcohol, then allowing the resulting solution to cool. Breakdown of the relatively scentless ambrein through oxidation produces ambroxan and ambrinol, the main odor components of ambergris.

Ambrein

Ambroxan

Ambrinol

Ambroxan is now produced synthetically and used extensively in the perfume industry.[15]

Applications[]

Ambergris has been mostly known for its use in creating perfume and fragrance much like musk. Perfumes can still be found with ambergris.[16] Ambergris has historically been used in food and drink. A serving of eggs and ambergris was reportedly King Charles II of England's favorite dish.[17] A recipe for Rum Shrub liqueur from the mid 19th century called for a thread of ambergris to be added to rum, almonds, cloves, cassia, and the peel of oranges in making a cocktail from The English and Australian Cookery Book.[18] It has been used as a flavoring agent in Turkish coffee[19] and in hot chocolate in 18th century Europe.[20] The substance is considered an aphrodisiac in some cultures.[21]

Ancient Egyptians burned ambergris as incense, while in modern Egypt ambergris is used for scenting cigarettes.[22] The ancient Chinese called the substance "dragon's spittle fragrance".[23] During the Black Death in Europe, people believed that carrying a ball of ambergris could help prevent them from contracting plague. This was because the fragrance covered the smell of the air which was believed to be a cause of plague.

During the Middle Ages, Europeans used ambergris as a medication for headaches, colds, epilepsy, and other ailments.[23]

Legality[]

From the 18th to the mid-19th century, the whaling industry prospered. By some reports, nearly 50,000 whales, including sperm whales, were killed each year. Throughout the 1800s, "millions of whales were killed for their oil, whalebone, and ambergris" to fuel profits, and they soon became endangered as a species as a result.[24] Due to studies showing that the whale populations were being threatened, the International Whaling Commission instituted a moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982. Although ambergris is not harvested from whales, many countries also ban the trade of ambergris as part of the more general ban on the hunting and exploitation of whales.

Urine, faeces and ambergris (that has been naturally excreted by a sperm whale) are waste products not considered parts or derivatives of a CITES species and are therefore not covered by the provisions of the convention.[25]

Illegal

- Australia – Under federal law, the export and import of ambergris for commercial purposes is banned by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The various states and territories have additional laws regarding ambergris.[26]

- United States – The possession and trade of ambergris is prohibited by the Endangered Species Act of 1973.[27]

Legal

In popular culture[]

This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (July 2017) |

Historical[]

The knowledge of ambergris and how it is produced may have been kept secret. Ibn Battuta wrote about ambergris, "I sent along with them all the things that I valued and the gems and ambergris..."[29] Glasgow apothecary John Spreul told the historian Robert Wodrow about the substance but said he had never told anyone else.[30]

In literature[]

In chapter 91 of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick (1851), Stubb, one of the mates of the Pequod, fools the captain of a French whaler (Rose-bud) into abandoning the corpse of a sperm whale found floating in the sea. His plan is to recover the corpse himself in hopes that it contains ambergris. His hope proves well founded, and the Pequod's crew recovers a valuable quantity of the substance.[31] Melville devotes the following chapter to a discussion of ambergris, with special attention to the irony that "fine ladies and gentlemen should regale themselves with an essence found in the inglorious bowels of a sick whale."[32]

In A Romance of Perfume Lands or the Search for Capt. Jacob Cole, F. S. Clifford, October 1881, the last chapter concerns one of the novel's characters discovering an area of a remote island which contains large amounts of ambergris. He hopes to use this knowledge to help make his fortune in the manufacture of perfumes.[33]

References[]

- ^ "Ambergris". Britannica. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Burr, Chandler (2003). The Emperor of Scent: A Story of Perfume, Obsession, and the Last Mystery of the Senses. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50797-7.

- ^ Panten, J. and Surburg, H. 2016. Flavors and Fragrances, 3. Aromatic and Heterocyclic Compounds. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. 1–45.

- ^ "Jovoy Paris 'Designed' for Fascinating Olfactory Experiences". Ikon London Magazine. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 794.

- ^ Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 66.

- ^ William F. Perrin; Bernd Wursig; J. G.M. Thewissen (2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0080919935.

- ^ Kemp, Christopher (2012). Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris. University of Chicago Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-226-43036-2.

- ^ Daley, Jason (14 April 2016). "Your High-End Perfume Is Likely Part Whale Mucus". Smithsonian. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ "A group of fishermen netted a $1.5 million whale-vomit windfall after dredging up a 280-pound hunk of the stuff". Business Insider.

- ^ Baldanza, Angela; Bizzarri, Roberto; Famiani, Federico; Monaco, Paolo; Pellegrino, Roberto; Sassi, Paola (30 July 2013). "Enigmatic, biogenically induced structures in Pleistocene marine deposits: A first record of fossil ambergris". Geology. 41 (10): 1075. Bibcode:2013Geo....41.1075B. doi:10.1130/G34731.1.

- ^ Ruzicka, L.; Lardon, F. (1946). "Zur Kenntnis der Triterpene. (105. Mitteilung) Über das Ambreïn, einen Bestandteil des grauen Ambra". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 29 (4): 912–921. doi:10.1002/hlca.19460290414.

- ^ Prelog, Vladimir; Jeger, Oskar (1980). "Leopold Ruzicka (13 September 1887 – 26 September 1976)". Biogr. Mem. Fellows R. Soc. 26: 411–501. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1980.0013.

- ^ Hillier, Stephen G.; Lathe, Richard (2019). "Terpenes, hormones and life: Isoprene rule revisited". Journal of Endocrinology. 242 (2): R9–R22. doi:10.1530/JOE-19-0084. PMID 31051473.

- ^ "Ambrox/Ambroxan: a Modern Fascination on an Elegant Material". Perfume Shrine. 5 November 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Spitznagel, Eric (January 12, 2012). "Ambergris, Treasure of the Deep". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Lord Macaulay (1848). "IV". The History of England from the Accession of James II. 1. Harper. p. 222.

- ^ Abbott, Edward (1864). The English and Australian Cookery Book. p. 272 (at the top).

- ^ "The starting point of Turkish coffee: Istanbul's historic coffeehouses". The Istanbul Guide. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Green, Matthew (March 11, 2017). "How the decadence and depravity of London's 18th century elite was fuelled by hot chocolate". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ "The Origin of Ambergris".

- ^ Brady, George Stuart; Clauser, Henry R.; Vaccari, John A. (2002). "Ambergris". Materials Handbook: An Encyclopedia for Managers, Technical Professionals, Purchasing and Production Managers, Technicians, and Supervisors. McGraw-Hill. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-07-136076-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Graber, Cynthia (April 26, 2007). "Strange but True: Whale Waste Is Extremely Valuable". Scientific American. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ Sherrow, Victoria L. (2001). For Appearance' Sake: The Historical Encyclopedia of Good Looks, Beauty, and Grooming. Greenwood. pp. 129. ISBN 9781573562041.

- ^ CITES CoP16 Com. II Rec. 2 (Rev. 1), Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Sixteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok (Thailand), 3–14 March 2013 Summary record of the second session of Committee II

- ^ "Whale and Dolphin permits – Ambergris". Environment.gov.au. 1979-06-28. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ "Ambergris, Treasure of the Deep". Businessweek. 2012-01-12. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Ambergris: lucky, lucrative and legal?".

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 249. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ^ Wodrow, Robert; Leishman, Matthew (1842). "May 28". Analecta: or, Materials for a history of remarkable providences; mostly relating to Scotch ministers and Christians. 1. Glasgow: Maitland Club. p. 7. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Moby-Dick, Chapter 91 at Wikisource.

- ^ Moby-Dick, Chapter 92 at Wikisource.

- ^ Perfumer, Clifford (1875). The Romance of Perfume. Boston: Clifford, Perfumer. pp. 284–295 (360–373 in the PDF). Retrieved January 31, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading[]

- Borschberg, Peter (April 2004). Pinto, Carla Alferes (ed.). "O comércio de âmbar asiático no início da época moderna (séculos XV–XVIII)" [The Asiatic Ambergris trade in the early modern period (15th to 18th century)]. Oriente (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Fundação Oriente. 8: 3–25. montalvoeascinciasdonossotempo.blogspot, accessed 21 August 2015

- Clarke, Robert (2006). "The origin of ambergris". Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals. 5 (1): 7–21. doi:10.5597/lajam00087.

- Dannenfeldt, Karl H. (1982). "Ambergris: The Search for Its Origin" (PDF). Isis. 73 (268): 382–97. doi:10.1086/353040. JSTOR 231442. PMID 6757176. S2CID 30323379. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-24.

- Dudley, Paul (1724). "An Essay upon the Natural History of Whales, with a Particular Account of the Ambergris Found in the Sperma Ceti Whale. In a Letter to the Publisher, from the Honourable Paul Dudley, Esq; F. R. S". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 33 (381–91): 256–69. Bibcode:1724RSPT...33..256D. doi:10.1098/rstl.1724.0053. JSTOR 103782. S2CID 186208376.

- Kemp, Christopher (2012). Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-43036-2.

- Kemp, Christopher (2012). "The Origin of Ambergris". Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 8–16. ISBN 978-0-226-43036-2.

- Kovatcheva, Assia; Golbraikh, Alexander; Oloff, Scott; Xiao, Yun-De; Zheng, Weifan; Wolschann, Peter; Buchbauer, Gerhard; Tropsha, Alexander (2004). "Combinatorial QSAR of Ambergris Fragrance Compounds" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 44 (2): 582–95. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.411.7708. doi:10.1021/ci034203t. PMID 15032539. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-22.

- Ohloff, Günther; Vial, Christian; Wolf, Hans Richard; Job, Kurt; Jégou, Elise; Polonsky, Judith; Lederer, Edgar (1980). "Stereochemistry-Odor Relationships in Enantiomeric Ambergris Fragrances". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 63 (7): 1932–46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.880.1000. doi:10.1002/hlca.19800630721.

External links[]

| Look up ambergris in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Perfume ingredients

- Whale products

- Animal glandular products

- Natural products

- Traditional medicine