Amoy dialect

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Amoy/Xiamen | |

|---|---|

| Amoynese, Xiamenese | |

| 廈門話 Ē-mn̂g-ōe | |

| Native to | China, Taiwan |

| Region | Xiamen (Amoy) and its surrounding metropolitan area |

Native speakers | over 10 million (no recent data)[citation needed] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | xiam1236 |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-je > 79-AAA-jeb |

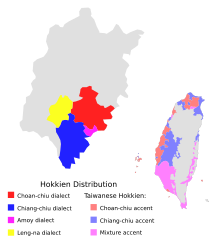

Distribution of Hokkien dialects. Amoy dialect is in magenta. | |

The Amoy dialect or Xiamen dialect (Chinese: 廈門話; pinyin: xiàménhuà; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ē-mn̂g-ōe), also known as Amoynese, Amoy Hokkien, Xiamenese or Xiamen Hokkien, is a dialect of Hokkien spoken in the city of Xiamen (historically known as "Amoy") and its surrounding metropolitan area, in the southern part of Fujian province. Currently, it is one of the most widely researched and studied varieties of Southern Min.[1] It has historically come to be one of the more standardized varieties.[2] Most present-day publications in Southern Min are mostly based on this dialect.[citation needed]

Spoken Amoynese and Taiwanese are both mixtures of the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou spoken dialects.[3] As such, they are very closely aligned phonologically. However, there are some subtle differences between the two, as a result of physical separation and other historical factors. The lexical differences between the two are slightly more pronounced.[citation needed] Generally speaking, the Southern Min dialects spoken in Xiamen, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Taiwan, Southeast Asia and Overseas Communities are mutually intelligible, with only slight differences.[4]

History[]

In 1842, as a result of the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, Amoy was designated as a trading port in Fujian. Amoy and Kulangsu rapidly developed, which resulted in a large influx of people from neighboring areas such as Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. The mixture of these various accents formed the basis for the Amoy dialect.

Over the last several centuries, a large number of from these same areas migrated to Taiwan during Dutch rule and Qing rule. "Amoy dialect" was considered the vernacular of Taiwan.[5] Eventually, the mixture of accents spoken in Taiwan became popularly known as Taiwanese during Imperial Japanese rule. As in American and British English, there are subtle lexical and phonological differences between modern Taiwanese and Amoy Hokkien; however, these differences do not generally pose any barriers to communication. Amoy dialect speakers also migrated to Southeast Asia, mainly in the Philippines (where it is known as Lán-nâng-ōe), Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

Special characteristics[]

Spoken Amoy dialect preserves many of the sounds and words from Old Chinese. However, the vocabulary of Amoy was also influenced in its early stages by the languages of the ancient Minyue peoples.[6] Spoken Amoy is known for its extensive use of nasalization.

Unlike Mandarin, Amoy dialect distinguishes between voiced and voiceless unaspirated initial consonants (Mandarin has no voicing of initial consonants). Unlike English, it differentiates between unaspirated and aspirated voiceless initial consonants (as Mandarin does too). In less technical terms, native Amoy speakers have little difficulty in hearing the difference between the following syllables:

| unaspirated | aspirated | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| bilabial stop | bo 母 | po 保 | pʰo 抱 |

| velar stop | go 俄 | ko 果 | kʰo 科 |

| voiced | voiceless | ||

However, these fully voiced consonants did not derive from the Early Middle Chinese voiced obstruents, but rather from fortition of nasal initials.[7]

Accents[]

A comparison between Amoy and other Southern Min languages can be found there.

Tones[]

Amoy is similar to other Southern Min variants in that it makes use of five tones, though only two in checked syllables. The tones are traditionally numbered from 1 through 8, with 4 and 8 being the checked tones, but those numbered 2 and 6 are identical in most regions.

| Tone number | Tone name | Tone letter |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yin level | ˥ |

| 2 | Yin rising | ˥˧ |

| 3 | Yin falling | ˨˩ |

| 4 | Yin entering | ˩ʔ |

| 5 | Yang level | ˧˥ |

| 6=2 | Yang rising | ˥˧ |

| 7 | Yang falling | ˧ |

| 8 | Yang entering | ˥ʔ |

Tone sandhi[]

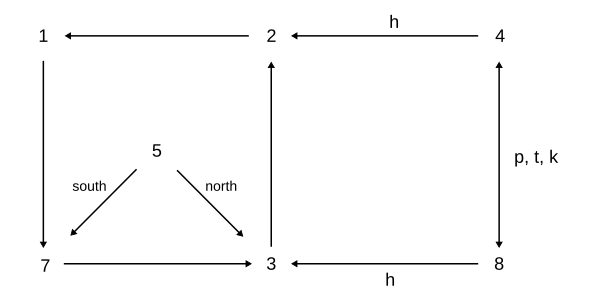

Amoy has extremely extensive tone sandhi (tone-changing) rules: in an utterance, only the last syllable pronounced is not affected by the rules. What an 'utterance' is, in the context of this language, is an ongoing topic for linguistic research. For the purpose of this article, an utterance may be considered a word, a phrase, or a short sentence. The diagram illustrates the rules that govern the pronunciation of a tone on each of the syllables affected (that is, all but the last in an utterance):

Literary and colloquial readings[]

Like other languages of Southern Min, Amoy has complex rules for literary and colloquial readings of Chinese characters. For example, the character for big/great, 大, has a vernacular reading of tōa ([tua˧]), but a literary reading of tāi ([tai˧]). Because of the loose nature of the rules governing when to use a given pronunciation, a learner of Amoy must often simply memorize the appropriate reading for a word on a case by case basis. For single-syllable words, it is more common to use the vernacular pronunciation. This situation is comparable to the on and kun readings of the Japanese language.

The vernacular readings are generally thought to predate the literary readings; the literary readings appear to have evolved from Middle Chinese.[citation needed] The following chart illustrates some of the more commonly seen sound shifts:

| Colloquial | Literary | Example | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [p-], [pʰ-] | [h-] | 分 | pun | hun | divide |

| [ts-], [tsʰ-], [tɕ-], [tɕʰ-] | [s-], [ɕ-] | 成 | chiâⁿ | sêng | to become |

| [k-], [kʰ-] | [tɕ-], [tɕʰ-] | 指 | kí | chí | finger |

| [-ã], [-uã] | [-an] | 看 | khòaⁿ | khàn | to see |

| [-ʔ] | [-t] | 食 | chia̍h | si̍t | to eat |

| [-i] | [-e] | 世 | sì | sè | world |

| [-e] | [-a] | 家 | ke | ka | family |

| [-ia] | [-i] | 企 | khiā | khì | to stand |

Vocabulary[]

- For further information, read the article: Swadesh list

The Swadesh word list, developed by the linguist Morris Swadesh, is used as a tool to study the evolution of languages. It contains a set of basic words which can be found in every language.

- The Amoy Min Nan Swadesh list

- The Sino-Tibetan Swadesh lists (Mandarin, Amoy, Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka, Burmese)

Phonology[]

Initials[]

| Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | ʔ | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | b | ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tɕ | |||

| aspirated | tsʰ | tɕʰ | ||||

| voiced | dz | dʑ | ||||

| Fricative | s | ɕ | h | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Approximant | l | |||||

- Word-initial alveolar consonants /ts, tsʰ, dz/ when occurring before /i/ are pronounced as alveo-palatal sounds [tɕ, tɕʰ, dʑ].

- /l/ can fluctuate freely in initial position as either a flap or voiced stop [ɾ], [d].

- [ʔ] can occur in both word initial and final position.

- /m ŋ/ when occurring before /m̩ ŋ̍/ can be pronounced as voiceless sounds [m̥], [ŋ̊].

Finals[]

| a 阿 |

ɔ 乌 |

i 魚 |

e 火 |

o 好 |

u 母 |

ɨ | /ai/ 愛 |

/au/ 抱 | |

| /i/- | /ia/ 写 |

/io/ 后 |

/iu/ 救 |

/iau/ 鸟 | |||||

| /u/- | /ua/ 花 |

/ue/ 話 |

/ui/ 水 |

/uai/ 歪 |

| /m̩/ 毋 |

/am/ 暗 |

/an/ 按 |

/ŋ̍/ 黃 |

/aŋ/ 港 |

/ɔŋ/ 風 | |

| /im/ 心 |

/iam/ 薟 |

/in/ 今 |

/iɛn/ 免 |

/iŋ/ 英 |

/iaŋ/ 雙 |

iɔŋ 恭 |

| /un/ 恩 |

/uan/ 完 |

| /ap/ 十 |

/at/ 克 |

/ak/ 六 |

/ɔk/ 乐 |

/aʔ/ 鸭 |

ɔʔ 索 |

oʔ 學 |

/eʔ/ 欲 |

/auʔ/ 落 |

ãʔ 肉 |

ɔ̃ʔ 乎 |

/ẽʔ/ 夹 |

ãiʔ 唉 | ||||||

| ip 急 |

/iap/ 葉 |

/it/ 必 |

/iɛt/ 阅 |

/ik/~/ek/ 色 |

/iɔk/ 祝 |

iʔ 捏 |

/iaʔ 食 |

ioʔ 尺 |

/iuʔ/ 搐 |

/ĩʔ/ 物 |

iãʔ 贏 |

|||||||

| /ut/ 骨 |

/uat/ 越 |

/uʔ/ 嗍 |

/uaʔ/ 活 |

/ueʔ/ 喂 |

- Final consonants are pronounced as unreleased [p̚ t̚ k̚].

| /ã/ 三 |

/ɔ̃/ 魯 |

/ẽ/ 明 |

/ãi/ 歹 |

|||

| /ĩ/ 暝 |

/iã/ 定 |

/iũ/ 想 |

/ãu/ 腦 | |||

| /uã/ 山 |

/uĩ/ 莓 |

/uãi/ 彎 |

Grammar[]

Amoy grammar shares a similar structure to other Chinese dialects, although it is slightly more complex than Mandarin. Moreover, equivalent Amoy and Mandarin particles are usually not cognates.

Complement constructions[]

Amoy complement constructions are roughly parallel to Mandarin ones, although there are variations in the choice of lexical term. The following are examples of constructions that Amoy employs.

In the case of adverbs:

伊

i

he

走

cháu

runs

會

ē

obtains

緊

kín

quick

He runs quickly.

- Mandarin: tā pǎo de kuài (他跑得快)

In the case of the adverb "very":

伊

i

He

走

cháu

runs

真

chin

obtains

緊

kín

quick

He runs very quickly.

- Mandarin: tā pǎo de hěn kuài (他跑得很快)

伊

i

He

走

cháu

runs